Susan Palwick is a wonderful writer. I think of her as a hidden gem. All of her books are worth seeking out.

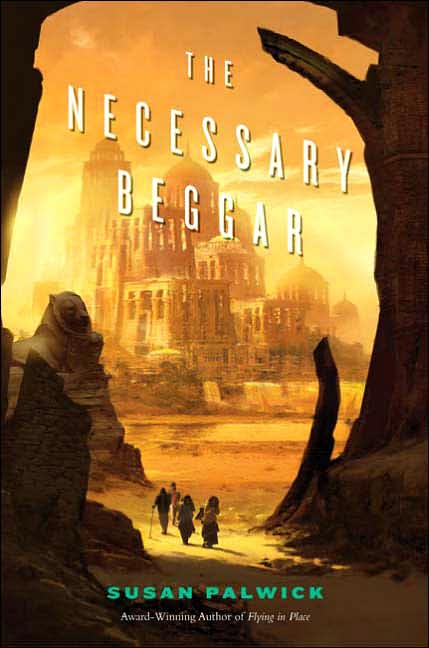

The Necessary Beggar is a book that defies classification. It is unique in my experience in being a book about people from a fantasy world who emigrate to the near future US. They are exiled from their own world and sent through a magic gate to arrive in a refugee camp in the Nevada desert. They have all the kinds of problems refugee immigrants normally have, plus the problems that they don’t come from anywhere they can point to on a map and the customs and expectations and recipes they’ve brought from home are a little odder than normal. Of course, they also have the problems they brought with them from home, and some of those problems need magical answers.

This is a book that could go terribly wrong. Palwick walks a tightrope here, avoiding sentimentality, cliche and appropriation but still winning through to a positive resolution. It only just works, and I can see how for some readers it might fall down. Unlike most fantasy, this is a book with a political point of view—it’s against internment camps for refugees and in favor of a U.S. health service and social safety net. If you take a different position you might find the book harder to swallow, because the position is very definite.

There’s a question of the smoothness of the eventual resolution and the fact that, when you stop and think about it, the whole thing depends on lack of communication. That works for me because difficulty of communication is a theme. I like this book a lot, but even so when I found out what had actually happened with Darotti and Gallicena I rolled my eyes. If you’re less in sympathy with it, I can see that being a problem.

But it really is a terrific book because it talks about the immigrant issue without minimizing or glamorizing. This could have exactly the same weirdness as with the homeless in Wizard of the Pigeons except a hundred times worse. But it doesn’t. It feels entirely right. There’s a thing that only fantasy can do where you take something real and by transforming it you get to the real essence of the thing. You get to a point where you can say something more true about the real thing because you’ve stepped out of reality. So here with the immigrant situation—the family here are literally the only people who speak their language and remember the customs of their home. They have literal ghosts and memories of places they really cannot go back to. It steps beyond metaphor and really gets something. When the younger generation are losing their old ways and becoming American, the old ways are magical but apply to the old world. The rules really are different in this world.

The story is told partly in three points of view, first person of the grandfather, Timbor, third person of his son Darotti (mostly in memories and as a ghost) and a kind of omniscient point of view centered around the grand-daughter Zamatryna. These work together surprisingly smoothly, in much the same way that Palwick makes the culture and customs of the magical city of Lemabantunk seem just as real as those of the America in which the characters seek a new home. She creates a solid-feeling secondary world, one with something of an “Arabian Nights” flavor, and thrusts it against reality without either side feeling neglected.

The reason this works so well is because it’s all told at the same level of reality—the physical and cultural and magical reality of the magical world, the physical and cultural and magical reality of America. There’s a depth and detail to this book that makes it stand out even apart from anything else. It is above all else the story of a family who feel absolutely real.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.