Before “paranormal romance” or “urban fantasy” existed as genres, there were occasional fantasies that just happened to be set in the real world and the modern day. They were pretty different from each other, and from the paranormal genres as they evolved, but they laid a layer of humus that became part of the topsoil from which those genres emerged. At the time, we didn’t know that, and we didn’t really know what to call these stories. Some of them were much closer to what was going to define the genres than others. Bull’s War For the Oaks (1987) had Sidhe playing in a rock band in Minneapolis. McKinley’s Sunshine (2004) had a vampire almost-romance. Charles De Lint also wrote a lot of things that led in this direction.

I first noticed this kind-of-subgenre in 1987 when I was working in London. I read Bisson’s Talking Man (1986), MacAvoy’s Tea With the Black Dragon (1983) and Megan Lindholm’s Wizard of the Pigeons (1986) all within a couple of weeks. Look, I said to myself, here are people who aren’t reaching back to Tolkien or to British and European folklore, they are doing something new, they are writing American fantasy!

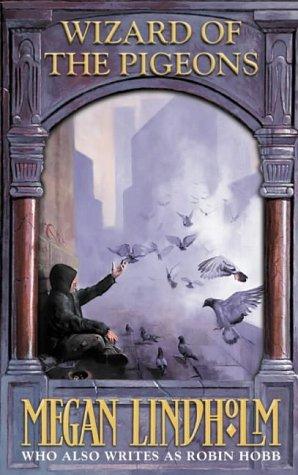

Of course, everybody knows that Megan Lindholm is now Robin Hobb, but I was a big fan of her books before the name change.

Wizard of the Pigeons was what hooked me. The owner of the local SF bookstore handed it to me and I started reading. It begins:

“On the far western shore of a northern continent, there was once a harbour city called Seattle. It did not have much of a reputation for sunshine and beaches, but it did have plenty of rain, and the folk who lived there were wont to call it ’the Emerald City’ for the greenness of its foliage. And the other thing it boasted was a great friendliness that fell upon strangers like its rain, but with more warmth. And in that city, there dwelt a wizard.”

I still love that paragraph, but it no longer seems so charmingly, astonishingly odd as it did in 1987—when I locked myself in the bathroom at work because I couldn’t bear to put the book down. (This really is the only job I’m fit to be trusted with!) What I thought then was that this was a children’s book for grown-ups. In the children’s fantasy of my childhood, like Alan Garner and Susan Cooper, you had children in real places coming across the fantastic underlying the scenery of their daily lives and having adventures with it. I had not previously read anything intended for adults that had that feel—Talking Man and Tea With the Black Dragon were what I got when I asked for more.

Wizard of the Pigeons is about a wizard (called Wizard) who is a homeless Vietnam vet in Seattle. There are other magical homeless people there too, who he interacts with, as well as a magical enemy. The book is uneven and oddly poised between the fairytale and the everyday. It’s about Wizard wandering around Seattle having a day and at its best it is glitteringly brilliant. It falls down a bit when it’s trying to have a plot. Lindholm has held this balance better since in the Nebula nominated novella “Silver Lady and the Fortyish Man” (1989). But it succeeds in having a genuine fairytale feel and genuine fairytale logic while being both totally original and firmly grounded in the reality of Seattle.

I have one problem with it that I didn’t have in 1987—these days I’m not comfortable with glamourizing the homeless and making their lives and problems magical. Back then I saw it as being like the wise beggars and tramps in fantasy worlds, and I suppose there’s no harm done if it makes people feel they’re giving spare change to someone who just might be magical. Still, now that homelessness is more of a problem I feel weird about the way Lindholm treats it here. I think I feel weirder because of being made really grumpy about this by Tepper’s Beauty, in which large numbers of the homeless are time travelers from the future sponging on our resources. Lindholm isn’t dismissive of the genuine problem in the same way.

This is early eighties Seattle, in which Starbucks was one shop. I expect people familiar with Seattle will find more things to notice—does the city still have a free ride area on the buses? I still haven’t been there. But I have no doubt that if I went there the street plan would be the way Lindholm says it is, give or take thirty years of evolution. I’ve never been to Seattle, but I could find my way around it the way I could Roke or Rivendell.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.