Most of the French salon fairy tale writers lived lives mired in scandal and intrigue. Few, however, were quite as scandalous as Henriette Julie de Murat (1670?—1716), who, contemporaries whispered, was a lover of women, and who, authorities insisted, needed to spend some quality in prison, and who, she herself insisted, needed to dress up as a man in order to escape said prison—and this is before I mention all of the rumors of her teenage affairs in Brittany, or the tales of how she more than once wore peasant clothing in the very halls of Versailles itself.

Oh, and she also wrote fairy tales.

Partly because her life was mired in scandals that she, her friends, and family members wanted to suppress, and partly because many documents that could have clarified information about her life were destroyed in the French Revolution and in World War II, not all that much—apart from the scandalous stories—is known about Madame de Murat, as she was generally known. Most sources, however, seem to agree that Henriette Julie de Castelnau Murat, was born in Brest, Brittany in 1670, and was the daughter of a marquis. I say “most sources” since some scholars have argued that Murat was actually born in the Limousin (now Nouvelle-Aquitaine) area, and a few more recent studies have claimed that she was actually born in Paris in 1668, and no one seemed completely certain about the marquis part, although she was born into the aristocracy.

Records about her later life are often equally contradictory, when not, apparently, outright fabricated. For instance, something seems to be just a touch off with one of the more famous stories about her, apparently first told in 1818, a century after her death, by the respectable lawyer Daniel Nicolas Miorcec de Kerdanet. According to this tale, shortly after her presentation at court and marriage, she impressed (according to some accounts) or scandalized (according to more prim accounts) Queen Maria Theresa of Spain, Louis XIV’s first wife, by wearing peasant clothing from Brittany in the royal presence. (You can all take a moment to gasp now.) Reported by numerous fairy tale scholars, the tale certainly fits with the rest of her scandalous stories told about her life, but, assuming that Murat was born in 1670 (as most of the people repeating this tale claim) and married at the age of 16 (as suggested by other documents), the earliest date for this scandal would have been sometime in 1686—three years after Maria Theresa’s death in 1683.

It is of course very possible that Miorcec de Kerdanet confused Maria Theresa with Madame de Maintenon, Louis XIV’s second, considerably less publicized wife, but nonetheless, this sort of easily checked error does not entirely inspire confidence in other tales about her—including his report that Murat had already enjoyed several wildly romantic (read: sexual) relationships before her arrival in Versailles at the age of 16. I’m not saying she didn’t. I’m just saying that in this case, the respectable lawyer doesn’t strike me as the most trustworthy source. It’s also possible that Murat was, indeed, born in 1668, making it just barely possible that she was presented at court in 1683, at the age of 15—just in time to scandalize Maria Theresa on her deathbed.

Which is to say, feel free to treat pretty much everything you read in the next few paragraphs with some degree of skepticism.

We are, however, fairly certain that Madame de Murat spent her childhood in either Brittany, Limousin or Paris, or all three, possibly making one or two trips to Italy, or possibly never visiting Italy, or even leaving France, at all. As the daughter of a marquis, she was officially presented at the court of Versailles at some point—perhaps when she was sixteen, ready to be married, or perhaps when she was twenty, or perhaps somewhere in between this. At some point after this presentation—either in 1686 (if we believe that respectable attorney Miorcec de Kerdanet again) or in 1691 (if we believe some more recent French scholarship), Murat married Nicolas de Murat, Comte de Gilbertez. Soon afterwards, she seems to have started attending the French literary salons, where she met various fairy tale writers, including Madame d’Aulnoy, Marie-Jeanne L’Heritier and Catherine Bernard. Perhaps with their encouragement, or perhaps not, she began to write poems and entering literary competitions.

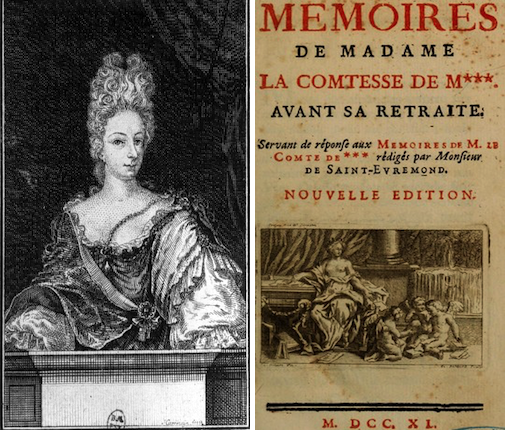

In 1697, she published a bestseller—Mémoires de Madame la Comtesse de M**** . The work was apparently intended less as a factual account of her marriage, and more as a response to Mémoires de la vie du comte D**** avant sa retraite, by Charles de Marguetel de Saint-Denis, seigneur de Saint-Evremond, a popular work which had appeared the year before—apparently without his authorization—and which depicted women as deceitful and incapable of living a virtuous life. (I should note that many objective observers said similar things about Saint-Evremond.) Madame de Murat’s own life may not have exactly been a paradigm of virtue by French standards—although the worst was yet to come—but she could not let these accusations stand. From her viewpoint, women were generally the victims of misfortune and gossip, not their perpetuators—even as she also blamed women for starting gossip, rather than working together in solidarity and mutual support. It was the first of many of her works to emphasize the importance of friendship between women.

The heroine of the memoir finds herself subject to emotional and physical abuse early in her marriage after an innocent visit from a former suitor—perhaps one of those alleged relationships back in Brittany. After fleeing, she was urged by family members, including her father, to return. How much of this reflected Murat’s own experiences is difficult to say. The available records suggest that her father died when she was very young, casting doubt upon that part of the tale, but other records and stories do suggest that Murat’s marriage was unhappy at best, and possibly abusive at worse. I could not find any record of her husband’s response to these accusations.

Presumably encouraged by her popular success, Murat turned to fairy tales, writing several collections as a direct response to Charles Perrault’s Histories ou contes du temps passé – the collection which brought us the familiar Puss-in-Boots, Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, and Sleeping Beauty, as well as the critical response to these tales. As someone who delighted in fairy tales, Madame de Murat did not object to their subject matter, but she did object to Perrault and various literary critics claiming that fairy tales were best suited for children and servants—mostly because that claim dismissed all of the careful, intricate work of the French salon fairy tale writers, many of them her friends. From de Murat’s point of view, she and her friends were following in the rich literary tradition of Straparola and other Italian literary figures, as well as helping to develop the literary form of the novel—not writing mere works for children. Even if some of the French fairy tale writers were writing works for children. As proof of her own intellectual accomplishments, she joined the Accademia dei Riccovrati of Padua—a group with a certain appreciation of the Italian literary tradition.

She also found herself embroiled in increasingly serious scandals at Versailles. By some accounts, she was first banished from court in 1694, after publishing the political satire Historie de la courtisanne. In 1699, a high ranking police officer of Paris, Rene d’Argenson, claimed that she was a lover of women, forcing Murat to flee Paris—and leave her husband—for some time. Two years later, she was discovered to be pregnant, which did nothing to convince anyone of her virtue. In 1702, she was exiled to the Chateau de Loches, at some distance from Paris.

All this should have been scandalous enough—but Murat added to it with a daring attempt to escape from the chateau, dressed as a man. Alas, her plan failed, and she was sent to various prisons before returning to the more pleasant half-prison of the Chateau de Loches in 1706.

The Chateau de Loches may have been an improvement from those prison, but Madame de Murat found exile deeply boring. To combat her boredom, she hosted late night gatherings which, depending upon who you choose to believe, were either nights of extreme debauchery and even orgies (whee!), or attempts to recreate the Paris salons she so missed, dedicated to witty conversation and fairy tales in this small chateau/half-prison and town far from Paris. Or both. None of this could have been exactly cheap, and exactly how she financed any of this remains unclear—but Murat decided that the parties should continue, and so they did.

When not hosting parties, she continued to write fairy tales and experimental novels, and—according to legends—further scandalized the locals by wearing red clothing to church. She was not allowed to return to Versailles and Paris until after Louis XIV’s death in 1715.

Sadly for those hoping for further scandal, Murat died shortly afterwards, in 1716.

Murat unabashedly admitted to plagiarizing ideas for many of her works—though that confession was also meant in part to inform her readers that she had, indeed, read Straparola and other literary figures, and thus should be considered a literary writer. She noted that other women, too, drew from Straparola—granting them this same literary authority—but at the same time, insisted that her adaptations had nothing to do with theirs: she worked alone. Thus, she managed to claim both literary authority and creativity. She may also have hoped that this claimed literary authority would encourage readers to overlook the more scandalous stories of sleeping with women, cross-dressing, and wearing inappropriate clothing to church.

In some cases, she outright incorporated the works of her fellow fairy tale writers, seemingly with their permission. Her novel A Trip to the Country, for instance, contains material definitely written by Catherine Bedacier Durand (1670—1736), and she continued to correspond and exchange tales with other fairy tale writers, some of whom occasionally dedicated works to her. This can make it difficult to know for certain which stories are absolutely, positively, definitely hers—Marina Warner, for one, prudently decided to say that one tale, “Bearskin,” was just “attributed to Henriette-Julie de Murat.” For the most part, however, tales firmly associated with Murat tend to be intricate, containing tales within tales, and often combine classical mythology with French motifs.

A fairly typical example is “The Palace of Revenge,” found in her collection Les nouveaux contes des fees, published in 1698—that is, four years after her possible first banishment from court, but shortly before her later imprisonment. It is a darkly cynical tale of love and fairies and stalking, containing within it another tale of possessive, forbidden love, one that—unlike the popular conception of fairy tales, starts happily and ends, well, a little less so. A king and queen of Iceland have a beautiful daughter named Imis, and a nephew, conveniently provided by Cupid, named Philax. Equally conveniently, the daughter and nephew fall in love, and find complete happiness—in the first three paragraphs.

This is about when things go wrong, what with unclear oracles (perhaps an echo of the vague fortunes told by questionable fortunetellers), not overly helpful fairies, enchanted trees that once were princes, and a small man named Pagan, who turns out to be a powerful enchanter. Pagan, convinced that he is far more in love and better suited to Imis than Philax is, begins to pursue her. Imis initially fails to take this seriously, convinced that her contempt for Pagan and obvious love for Philax will make Pagan retreat. The enchanter does not. Instead, Pagan transports Philax to a gloomy forest, and brings Imis to his palace, showering her with gifts and entertainment. The enchanted palace is somewhat like the one in Beauty and the Beast—but Imis is unmoved.

What does move her: finally seeing Philax again—happily throwing himself at the feet of another woman, a lovely nymph. As it happens, this is all perfectly innocent—Philax is throwing himself at the feet of the nymph out of gratitude, not love, but it looks bad, and Imis understandably assumes the worst. Nonetheless, even convinced of his infidelity, Imis decides to stay with Philax. Pagan takes his revenge by imprisoning them in a delightful enchanted castle—telling them that they will remain there forever.

A few years later, both are trying desperately—and unsuccessfully—to destroy the palace.

A story within the story tells of a fairy who, rather than showering gifts on reluctant suitors, enchanted them—and after they broke her enchantment, transformed them into trees. And trees they remain, if trees able to remember their lives as princes. Philax never tries to save them.

Murat would have, and did, sympathize with all of this: having her innocent actions mistaken for scandal, imprisonment in castles (if less enchanted and delightful than the ones she describes) and an inability to change at least some of those trapped by the more powerful—including herself. She knew of people like Pagan, unable to take no for an answer, and did not blame their victims—even as she recognized that those people might take their revenge. And she knew about magic. Thus her fairy tales: cynical, pointed, and not entirely able to believe in happy endings.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

Thank you! This showed up at exactly the right time for me to make Murat a minor character in a flash fiction I’m writing set in a 1690s Paris salon involving the telling of fairy tales. (I’d already included d’Aulnoy but I think Murat deserves a few lines.)

The big question is: Did she know Julia D’Aubigny?

Hi there! I found this article extremely interesting! I’m writing a thesis on Murat (and Aulnoy and Auneuil) and ended up here (it’s less about the author and more about the translation in italian, yada yada)

Could you list some sources though? I’d like to quote or expand on what you wrote but my supervisor won’t let me touch with a stick contents without sources ahah comprehensibly.