Innumerable Voices is a monthly column profiling short fiction writers and exploring speculative fiction themes in their many permutations. The column will discuss stellar genre work from both fresh and established writers who don’t have short fiction collections or novel-length works, but who actively contribute to anthologies and magazines.Links to magazines and anthologies for each story are available as footnotes. Chances are I’ll discuss the stories at length and mild spoilers will be revealed.

Historically, literature has been the truest playground where any vision can burn brightly in the mind of readers, no matter how complex, fantastical in its nature, and grand of scale. And yet motion pictures and theatre are better suited to capture the velocity of close combat as well as the kinetic energy and dynamic choreography intrinsic to dueling. It’s not impossible for fiction to match these achievements—but in the hands of a lesser writer, duels (or any form of physical altercation) can drone on, hollow and tedious to read, detracting rather than contributing to overall enjoyment. Charlotte Ashley is among the few writers I’ve read who tells a compelling story through her characters’ physicality; quick, precise, and elegant. For Ashley, duels, clashes and physical survival in various manifestations are the heart of the story, which inform the inner lives of her characters and their worlds.

“La Héron”[1] served as my introduction to Charlotte Ashley and is a story I often recall with fondness. Crisp, playful, and as fast as a hound after its quarry, the story centers on an illegal dueling tournament somewhere in France where mere mortals compete against fairy lords for high-stake prizes. The eponymous La Héron, a swordswoman extraordinaire, takes on both mortals and fantastical opponents with ensorcelled blades until she faces Herlechin of the Wild Hunt. The heart of adventure found in Alexander Dumas’ works beats here stronger than ever, and once you throw in the incomparable, loud-mouthed Sister Louise-Alexandrine, a nun with a penchant for violence, “La Héron” turns irresistible. On a sentence level, Ashley tends to each intricate detail, from the dancing blades to minute body language cues—a conversation without a single word uttered:

Herlechin moved first. He swung one blade down, a lightning strike sent straight for her heart, whirling the second like an echo toward her thigh. For her part, La Héron stepped back and twitched her sword’s point at the back of Herlechin’s gloved hand. First blood needn’t be fatal.

Herlechin repeated this cleaver-like attack three, four times, advancing on La Héron each time, forcing her farther and farther back toward a turret. The fairy lord was tireless, and La Héron’s counterattacks hadn’t enough weight behind them to breach his leather hide. Still, La Héron’s face showed only focus and control, study and thought.

As Herlechin drew up for the fifth attack, La Héron’s heel scraped against the stone wall. Herlechin guffawed to see her trapped, unable to retreat further, but La Héron’s lip only twitched in annoyance.

In “La Clochemar”[2], Soo (Suzette) finds opponents in both the French government during the early days of Canada as a colony and in the great spirits of indigenous First Nation lore that inhabit the deep Canadian forests as gigantic monsters. Ashley overlays real history with the fantastical, and her historical research gives texture to the environment and the politics of the time, providing a strong foundation over which the unreal looms, hyper-real and tangible. As one initiated into the tradition of runners, Suzette exists in both aspects of the same world, maneuvering through the treacherous machinations of humans and racing against death in the wilderness at the jaws of monolithic predators. It’s this interlacing of dangers that make the story shine, and also serves as an instruction on successfully integrating beloved fantastical tropes without sacrificing depth or substance.

This alternative history of Canada is further developed into “More Heat Than Light”[3] —a tale about Canada’s first steps towards emancipation and independence. Here, Ashley gives us just fractal glimpses of the monstrous fauna at the edges of civilization, which are still a real threat; this technique has the effect of heightening the dramatic tension and raising the stakes, as the mechanisms governing a revolution turn mercilessly. Ideals clash with hunger. Justice with propaganda. Lieutenant Louis-Ange Davy learns that freedom might be on the lips of many, but it’s forever hampered by our prejudices.

Contaminating the real, concrete, and historical with the fantastical comes effortlessly to Charlotte Ashley, and she finds equally stable footing in writing about the heyday of the Dutch Empire in “Eleusinian Myseries”[4] (which, for me, evoked the French silent film A Trip to the Moon), and exploring a setting based on the tumultuous 19th-century Balkans in “A Fine Balance”[5]. Both stories continue the lineage of women of action, who challenge assumptions about the lives of women in historical periods removed from current memory. This in itself can be deemed fantastical to those with limited and calcified views.

The former of the two showcases Ashley’s ability to tell a compelling story, makes you ache and grieve for her characters right from the start and then surprises with an ending that forces you to reassess what you thought you were reading. “A Fine Balance” has taken all that made “La Héron” exceptional, perfected it, and distilled it.

In a culture where dueling has ascended to a sacred ritual that mitigates political strain, two duelists, or Kavalye, have achieved near-mythical reputations for their endurance, prowess, and combat ability. This story is both a swift hunt, a performance piece for the public, and political arm-wrestling as Shoanna Yildirim and Kara Ramadami take each other on again and again. Here Ashley contaminates the real world from the other side of the barrier as she elevates the feats and achievements of these women to hyperbolic heights believable only when witnessed, thus relegating them to the realm of legends in subsequent generations.

The same effect, but in reverse, is utilized in other works set further along on the fantastical spectrum. The real infiltrates the unreal, grounds the otherworldly, and binds it to our reality in order to make it known and understood. Adhering to the rules of politics, the alliances, histories and negotiations between the nature spirits and beings of folklore in “The Will of Parliament”[6]—traditionally unknowable to us—become familiar and relatable. It gives us an in to a world not meant for human eyes, and gives Ashley the freedom to invent and ornament her setting. The preoccupation with domesticity and living in the midst of a saga-worthy war delivered with a deadpan sense of humor in “Sigrid Under the Mountain”[7] transforms the presence of kobolds from a mystical intrusion that disturbs the order of things to a lived-in reality that merits little panic. In “Drink Down the Moon”[8], discovering the delights and joys of the physical body is what shapes the fates of Maalik and Estraija outside the predetermined course of the war of angels. Ashley proves the real and the human, mundane as it is, can have just as much power as those unmovable forces outside human comprehension. The hint of a promise, an act of kindness, or the fulfillment of touch can rival any spell, any dominion over the elements.

What I find spectacular about Charlotte Ashley is her versatility. “Fold”[9] startles with its far-future vision of colonialism in outer space, which stands at odds with her main themes; but it still showcases a dynamic use of language and gives readers a fresh take on the trope of cat-and-mouse by setting the story on a planet where any and all construction is done via folding giant sheets of aluminum. Ashley finds her voice well-suited for science fiction, where her affinity for strange creatures has given us a space bestiary in the tongue-in-cheek, quip-filled “The Adventures of Morley and Boots”[10]—a successor to Firefly in spirit if I’ve ever read one. There’s an almost slapstick quality to the action scenes in which the crew of the Leapfrog move from one perilous situation to another under the firm, if somewhat reckless leadership of Captain Boots. While all the stories I’ve discussed above are, to an extent, wry and brush up against humor, here Ashley exercises her comedic chops and gives a good old-fashion adventure in the spirit of Robert Sheckley.

This playfulness is then fully contrasted in “The Posthuman Condition”[11], where the bestiary of frightful beings consists entirely of humans. It’s perhaps the most sinister piece in Ashley’s body of work, marrying science fiction with body horror as the concept of posthumanism evolves to its most extreme conclusion. “The Posthuman Condition” establishes a baseline reality that appears to us to be disgusting and alienating and then further pushes and breaches this reality by sowing a seed of the otherworldly. When it comes to posthumanism in fiction, I feel a common theme involves wondering, “When do humans stop being humans?” In the indifference that intern Jesse Bauman encounters and clashes against as she attempts to deal with two gruesome suicides, the reader sees Ashley pondering the value of life now that “[t]he human body is obsolete.”

This feels like a suitable place to conclude my profile, as I’ve trekked a long way from the fairy folk and swashbuckling adventures of eras past to limitless space and technology. Often, we hear the proclamation that a writer’s moral duty to their readers is to entertain. That’s what storytelling is about—opening up to someone else’s understanding of the world, vulnerable and willing to be reshaped as stories course through us and are eagerly devoured. Entertaining, however, does not exclude smart, witty, or profound. Charlotte Ashley goes above and beyond in her art to accommodate and please her audience with charismatic women of quick wit and flawlessly executed, cinematic action. Her writing draws you in with its vitality and thrills, but leaves you with a lot more to appreciate once you reach the final line.

Footnotes

[1] Published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, March/April 2015. Available to listen to as audio at PodCastle #431, August 30th 2016

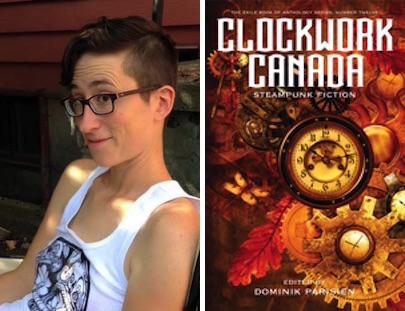

[2] Published in Clockwork Canada ed. Dominik Parisien, Exile Editions, 2016

[3] Published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, May/June 2016

[4] Published in Luna Station Quarterly #23, September 2015

[5] Upcoming in the The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Nov/Dec 2016

[6] Available to read at The Sockdolager, Winter 2015

[7] Available to read at The Sockdolager, Summer 2015

[8] Published at Chamber of Music, PSG Publishing, 2014

[9] Published in Lucky or Unlucky? 13 Stories of Fate, SFFWorld.com, 2013

[10] Available to read at The After Action Report, 2014

[11] Available to read at Kaleidotrope, Summer 2015

Haralambi Markov is a Bulgarian critic, editor, and writer of things weird and fantastic. A Clarion 2014 graduate, he enjoys fairy tales, obscure folkloric monsters, and inventing death rituals (for his stories, not his neighbors…usually). He blogs at The Alternative Typewriter and tweets @HaralambiMarkov. His stories have appeared in The Weird Fiction Review, Electric Velocipede, Tor.com, Stories for Chip, The Apex Book of World SF and are slated to appear in Genius Loci, Uncanny and Upside Down: Inverted Tropes in Storytelling. He’s currently working on a novel.