Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

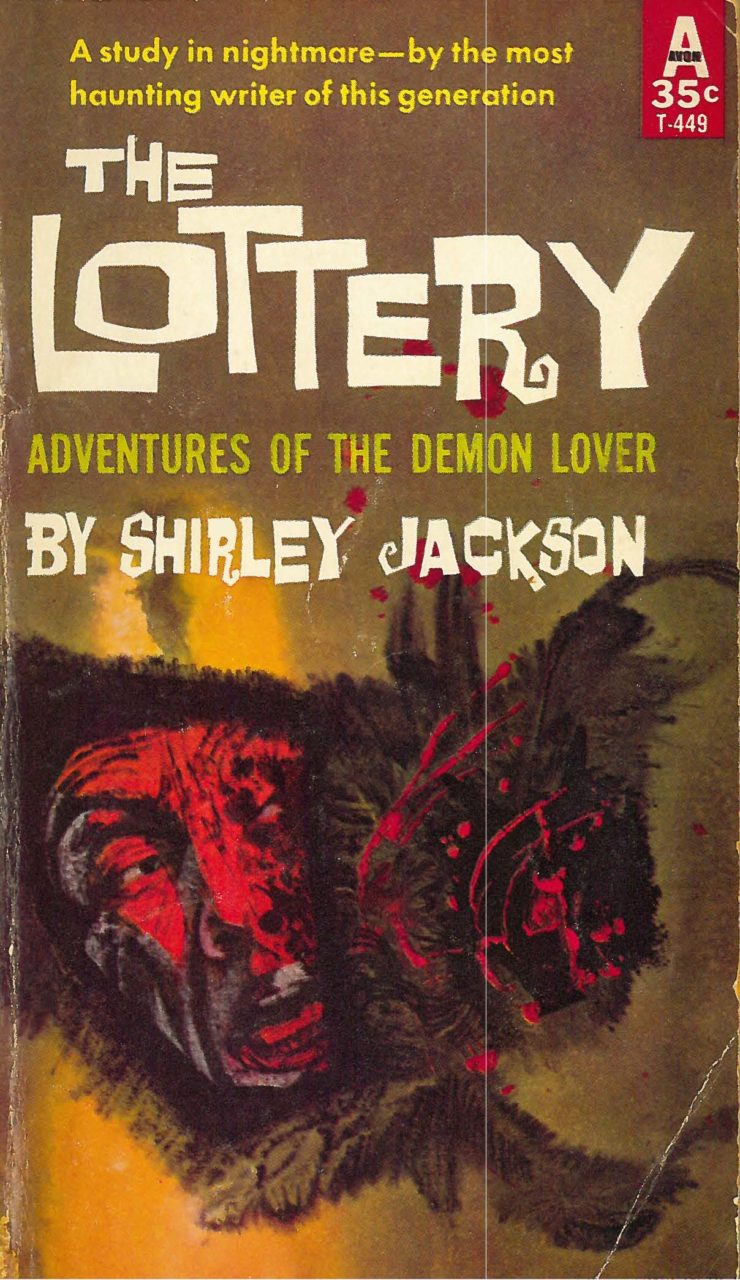

Today we’re looking at Shirley Jackson’s “The Daemon Lover,” first published in her The Lottery: The Adventures of James Harris collection in 1949. Spoilers ahead.

“Dearest Anne, by the time you get this I will be married. Doesn’t it sound funny? I can hardly believe it myself, but when I tell you how it happened, you’ll see it’s even stranger than that…”

Summary

Unnamed female narrator wakes on her wedding day—an unusual sort of wedding day, as she writes to her sister—before discarding the unfinished letter. She’s only known her fiance Jamie Harris a short time, and his proposal seems to have come out of nowhere.

She cleans her tiny apartment in preparation for their wedding night, remaking the bed and changing out towels every time she uses one. Which dress to wear is a tormenting decision: the staid blue silk Jamie’s already seen on her or the print he hasn’t? The print would give her a soft feminine look, but in addition to being too summery, it might look too girlish for her thirty-four years.

Jamie’s supposed to arrive at ten. He doesn’t. She remembers how they separated the night before, with her asking “Is this really true?” and him going down the hall laughing. Stoked on coffee and nothing else, since she won’t touch the food meant for their first breakfast as a married couple, she leaves briefly to eat. She pins up a note for Jamie. He’ll be there when she returns. Except he isn’t.

She sits by the window, falls asleep, wakes at twenty to one, “into the room of waiting and readiness, everything clean and untouched.” An “urgent need to hurry” sends her out in the print dress, hatless, with the wrong color purse. At Jamie’s supposed apartment building, none of the mailboxes bear his name. The superintendent and wife can’t remember any tall fair young man in a blue suit—as she describes him, for she can’t recall his face or voice. It’s always that way with the ones you love, isn’t it? Then the impatient couple recall a man who stayed in the Roysters’s apartment while they were away.

She climbs to 3B, to find the Roysters in all the disorder of unpacking. Jamie Harris? Well, he’s Ralph’s friend. No, Ralph says, he’s Dottie’s friend—she picked him up at one of her damn meetings. Anyhow, Jamie’s gone now. He left before they returned that morning.

She inquires at neighboring businesses for the tall fair man in the blue suit. A deli owner shoos her off. A news vendor says he may have seen such a fellow, yeah, around ten, yeah heading uptown, but as she hurries off, she hears him laughing about it with a customer.

A florist recalls a tall fair young man in a blue suit who bought a dozen chrysanthemums that morning. Chrysanthemums! She’s disappointed by such a pedestrian choice for wedding flowers, but heartened that Jamie must be en route to her apartment.

An old shoeshine man heightens her hope by claiming a young man with flowers stopped for a shine, dressed up, in a hurry, obviously a guy who’s “got a girl.”

She returns home, sure Jamie’s there, to find the apartment “silent, barren, afternoon shadows lengthening from the window.” Back in the street, she again accosts the shoeshine man. He points out the general direction of the house the young man entered. An impudent young boy is her next guide. He saw the guy with the flowers. The guy gave him a quarter and said, “This is a big day for me, kid.”

Her dollar bill buys the boy’s further intelligence that the guy went into the house next door, all the way to the top. But hey, he hollers. Is she going to divorce him? Does she got something on the poor guy?

The building seems deserted, front door unlocked, no names in the vestibule, dirty stairs. On the top floor she finds two closed doors. Before one is crumpled florist paper, and she thinks she hears voices inside. They still when she knocks. Oh, what will she do if Jamie’s there, if he answers the door? A second knock elicits what might be distant laughter, but no one comes to the door.

She tries the other door, which opens at her touch. She steps into an attic room containing bags of plaster, old newspapers, a broken trunk. A rat squeaks or rustles, and she sees it “sitting quite close to her, its evil face alert, bright eyes watching her.” As she stumbles out and slams the door, the print dress catches and tears.

And yet she knows there’s someone in the other room. She hears low voices, laughter. She comes back many times, “on her way to work, in the mornings; in the evenings on her way to dinner alone, but no matter how often or how firmly she knocked, no one ever came to the door.”

What’s Cyclopean: Jackson’s language is spare and direct. No cyclopeans present, or needed.

The Degenerate Dutch: Jackson’s narrator is painfully aware of how people dismiss an “older” woman’s worries.

Mythos Making: The world is not as you thought it was, and you can’t convince anyone to believe your experiences. Sound familiar?

Libronomicon: No books this week, unless you count the paper at the newsstand.

Madness Takes Its Toll: That link to the story above? Read the comments, and you’ll see how quickly a jilted—possibly demon-jilted—woman gets dismissed as neurotic or labeled as mentally ill. Apparently being confused and upset is a weird response to this situation. (Don’t read the comments.)

Anne’s Commentary

And the countdown to NecronomiCon 2017 continues! While I was going through the catalog to check that I was slated for panels on Lovecraft’s revisions and Miskatonic and the Mythos, I noticed I was also slated for a panel on Shirley Jackson. I didn’t ask for that assignment, but I was glad to accept it, as it gave me a chance to reread this master of subtle eeriness and the gothic terrors of modern life.

Jackson was born in 1916, just a year before Lovecraft took his great leap from juvenilia into “The Tomb” and “Dagon.” Of her childhood propensity for clairvoyance, she wrote, “I could see what the cat saw.” Howard would have liked that explanation, I think, for don’t the cats in his fiction see a great many obscure things? He would also have sympathized with Jackson’s liking for black cats—apparently she kept up to six of them at a time. Going to bet the family farm (well, plot in the community garden) that he would have placed The Haunting of Hill House high in his pantheon of supernatural literature.

“The Daemon Lover” appears in Jackson’s The Lottery, or the Adventures of James Harris. James Harris? Any relation to the Jamie Harris of today’s story? Could be. Could in fact be the very same guy, who’s as old at least as Scottish folklore and balladry. In case the subtitle of her collection isn’t enough of a hint, Jackson closes Lottery with an “epilogue” consisting entirely of an actual ballad about this character. “James Harris, the Daemon Lover” (Child Ballad No. 243) sees him carrying a woman off on his sumptuous ship. Before they’ve sailed far, she notices his eyes have gone “drumlie” (gloomy, muddy) and his feet cloven. As they pass a land of sunny and pleasant hills, the daemon Harris explains that this is heaven, which she’ll never win. As they pass a land of dreary frost-ridden mountains, he explains this is hell, for which they’re bound. Then he sinks the ship and drowns the hapless lady.

Yeah, I know. That kind of nonsense is what makes boat insurance so expensive.

You could read “The Daemon Lover” as a strictly realistic story. Nothing it contains, nothing that happens, has to be supernatural, and the title could be mere metaphor. The unnamed narrator could join the company of such jilted ladies of literature as Dickens’ Miss Havisham and Trollope’s Lily Dale, though drably Urban-Moderne to the former’s flamboyant madness and the latter’s long-suffering romance. Or, like me, you could aspire to see with the eyes of a cat and spy the uncanny in the shadows that lengthen through the piece, like the ones that darken our narrator’s apartment as afternoon passes without Jamie’s arrival.

Suspense is the emotional keynote of “Daemon Lover” from narrator’s early morning jitters, compulsive cleaning and apparel indecision through her increasingly panicked hunt for the missing (but surely only delayed) groom. How could things go well for our bride when Jamie left her the night before trailing laughter down the hall? Because, see, laughter is often a bad omen in Jackson’s fiction. People frequently laugh at her characters rather than with them. Derisive laughter. Mocking laughter. The superintendent and his wife laugh at the narrator. The news vendor and his customer laugh at her. The florist is nastily snide as he calls after her, “I hope you find your young man.” The informative boy makes raucous fun of her search, even as he aids it. And then, worst of all, there’s laughter behind the door on the top floor, where Jamie may have taken refuge.

With his chrysanthemums, which are not only a tacky flower for a wedding bouquet but a highly inauspicious one, since they have a strong folkloric association with funerals and burials.

While Lovecraft evokes terror with his vision of cosmic indifference to mankind, Jackson evokes it with the indifference of urban (suburban) masses to the individual. Her characters want to be seen, not ignored and shoved aside; to be named, not anonymous; to be acknowledged, appreciated, loved. Cthulhu is not their ultimate nightmare, but the demon that leads on and then slights, here the incubus-like Jamie. He destroys his “bride” as thoroughly as a ravening Great Old One could destroy humanity. How? By promising her companionship, a place in the community, and then deserting her, still ensorcelled into wanting him, seeking him. She tracks him to his lair, but nothing greets her there except a rat.

Its face is evil. Its bright eyes stare and mock. Could it be Jamie himself in rodent guise? Running from it, she tears her girlish dress, beyond repair we must suppose. Symbolic defloration may satisfy demons as well as the real thing.

On one level (his pessimistic one), Lovecraft sees our greatest danger in the possibility that we’re not alone in the cosmos. This is the opposite of the greatest danger Jackson perceives, the harsh curse that, man or devil, Jamie inflicts on his never-bride: He leaves her alone. Doomed to eat her dinners alone. Doomed to knock on never-opened doors.

Alone, shivering, like whatever it is that walks in Hill House, however numerous its ghosts.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Horror, and its supernatural elements, come in many gradations. At one end, the monsters howl in your face, letting you delineate each scale and ichor-dripping tooth. At the other end: Shirley Jackson’s “The Daemon Lover.” “Daemon Lover” could be read, if one wished, as a squarely mainstream literary story. A woman is disappointed in a relationship, and people act badly to her. Can we really even count this as horror?

But then there’s that title. “The Daemon Lover” is Child ballad #243, and James Harris (Jamie Harris, James Herres, etc.) the titular deceiver. Maybe just a literary reference to lovers mysteriously vanished, suggests my imaginary interlocutor who hates to admit any fiction less than perfectly mimetic. But then again, perhaps there’s a reason that she can’t picture his face. Perhaps there’s a reason that, as she suggests in the unsent letter to her sister, “when I tell you how it happened, you’ll see it’s even stranger than that.”

Kyle Murchison Booth, the protagonist of “Bringing Helena Back,” sees a different side of the ballad in one of his later stories. “Elegy for a Demon Lover” shows us the incubus face-on: not the once-faithful lover who vanishes into the night, but the lover who steals nights, and life itself. Yet the blurred edge of memory is common to both. Kyle, too, can’t recall his beloved’s face when it’s not in front of him. In both cases, a reminder that intimacy doesn’t mean you truly know someone—perhaps you never can.

Demon lovers lead you near to the altar and vanish. Demon lovers appear late at night to those with no imagined hope of a human lover, and trade love for life. Demon lovers feed on the trust at the core of human relationships. Even if you survive after they pass on to their next victim, other relationships may feel less real, less worthy of your confidence. After all, if one beloved disappears, how can you be sure that others won’t do the same?

Perhaps that’s why this story’s emotional arc feels so close to some of Lovecraft’s. No deep time civilizations pulling the rug out from under human importance, no unnamable monsters challenging our assumptions about our ability to cage reality in words—but our protagonist’s worldview is still turned upside down, and the whole story is about her admitting what the reader suspects from the first paragraph. About the distress and denial of coming around to that admission. Sit Jackson’s jilted bride down with Professor Peaslee, and they might have a surprising amount to talk about.

The fraying tissue of reality extends beyond the hard-to-remember Jamie, into the protagonist’s own selfhood. In some ways she seems almost as unmoored as he. She appears to have no best friend to go crying to, no family to offer advice (not even the sister to whom she doesn’t write). And no one in the story seems to treat her pain as real. If asked, how many people would remember her face? This invisibility can be a real hazard for women past the Approved Age, but that mundanity makes it no less surreal.

Walking the tightrope between literary realism and rising horror, “Daemon Lover” reminds me of “The Yellow Wallpaper.” There, too, the ordinary and supernatural interpretations are equally compelling and compatible. And there, too, that ambiguous edge stems from everyone’s failure to take a woman’s pain seriously. These moments of invisibility, the sense of walking outside shared reality until someone notices—perhaps these are more common than we like to admit. There’s a certain comfort, after all, in assuming it takes a monster to push you outside the safe confines of nameability.

Next week, Lovecraft and Duane Rimel’s “The Disinterment” demonstrates, yet again, that reanimating the dead isn’t as good an idea as you think.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” is now available from Macmillan’s Tor.com imprint. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.