When the good folks at Tor.com decided it would be awesome to follow up Steampunk October with a Cthulhu December, they were kind enough to invite me to kick things off. So: welcome, one and all, to Theme Month No. 2, our grand Countdown to Cthulhumas! For the next thirty-one days, we’ll poke our as-yet-unspecified protuberances into those perilous shadows of the uncaring cosmos first envisioned by H.P. Lovecraft most of a century ago. We can only imagine―if we dare!―what unspeakable terrors beyond human understanding they may find.

* * *

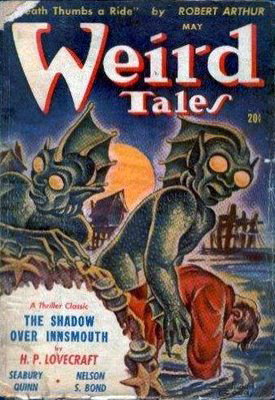

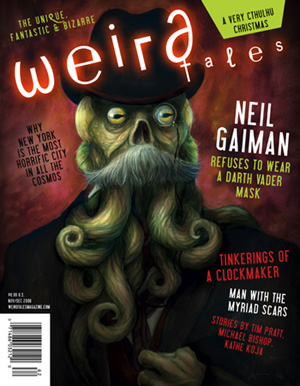

Let’s back up a moment. This is my first time blogging here, though I’ve been lurking since day one, so I should say a proper hello. I’m Stephen Segal, an earthling from the Jersey shore currently living in the Maryland outskirts of Washington, D.C., where I engage in a hodgepodge of professional geekery. Most notably, I’m the editorial and creative director at Weird Tales, the modern-day descendant of the magazine where H.P. Lovecraft published so much of his work.

With my partner in fantastical oddity, fiction editor Ann VanderMeer, I’ve spent the past several years banging around inside the machinery of the world’s oldest speculative-fiction vehicle, trying to distill the classic Weird Tales era’s most fundamental essence, its purest storytelling aesthetics, and translate that je ne sais quoi from a 1930s idiom, one that shaped the entire SF genre to follow, into a 21st-century idiom capable of impacting new readers today. Unsurprisingly, Lovecraft looms huge in the picture. His stories almost single-handedly redefined literature’s ancient tradition of supernatural horror for the modern age, replacing the fallen angel Lucifer and all the monstrous demons of a burning, mythological Hell with the buried alien Cthulhu and all the monstrous extraterrestrial revelations of a cold, scientific universe.

With my partner in fantastical oddity, fiction editor Ann VanderMeer, I’ve spent the past several years banging around inside the machinery of the world’s oldest speculative-fiction vehicle, trying to distill the classic Weird Tales era’s most fundamental essence, its purest storytelling aesthetics, and translate that je ne sais quoi from a 1930s idiom, one that shaped the entire SF genre to follow, into a 21st-century idiom capable of impacting new readers today. Unsurprisingly, Lovecraft looms huge in the picture. His stories almost single-handedly redefined literature’s ancient tradition of supernatural horror for the modern age, replacing the fallen angel Lucifer and all the monstrous demons of a burning, mythological Hell with the buried alien Cthulhu and all the monstrous extraterrestrial revelations of a cold, scientific universe.

That conceptual shift was staggering in the 1920s and ’30s―and yet four generations later, by which time one might have reasonably expected Lovecraft’s influence to have become just part of the cultural history underlying the work of more recent artists, the reality instead is that his own stories are more popular than ever. As Tor.com will make clear this month, we’re in the midst of a real Lovecraft boom: new reprints of the classic tales, new adaptations into visual art and film, new comics and stories and music and novels and Web sites built around the tentacled threat of Cthulhu and his ilk. That’s why I’ve found it impossible to tackle the challenge of reinvigorating Weird Tales without also addressing the question: why has Lovecraft endured? Why hasn’t H.P.L. faded beneath Bradbury and King and Gaiman the way Lord Dunsany has faded beneath Tolkien and Moorcock and Rowling?

That conceptual shift was staggering in the 1920s and ’30s―and yet four generations later, by which time one might have reasonably expected Lovecraft’s influence to have become just part of the cultural history underlying the work of more recent artists, the reality instead is that his own stories are more popular than ever. As Tor.com will make clear this month, we’re in the midst of a real Lovecraft boom: new reprints of the classic tales, new adaptations into visual art and film, new comics and stories and music and novels and Web sites built around the tentacled threat of Cthulhu and his ilk. That’s why I’ve found it impossible to tackle the challenge of reinvigorating Weird Tales without also addressing the question: why has Lovecraft endured? Why hasn’t H.P.L. faded beneath Bradbury and King and Gaiman the way Lord Dunsany has faded beneath Tolkien and Moorcock and Rowling?

All sorts of answers present themselves: Lovecraft’s stories are really, really spooky. Cthulhu is an unforgettable creature. The author had several protégés who kept pushing his legacy after he died. All that is true, and yet it seems to me that none of it is really enough to explain why this dead old New Englander still strikes people today as so darn relevant.

I propose we step away from the iconic figure of H.P. Lovecraft, originator of cosmic horror, genre author of the century. Instead… take a look at plain old Howard Lovecraft, skinny dude from Rhode Island. Go on, look at him. And don’t just look at that one headshot, either, where he’s grimacing past the camera like he’s on the toilet trying to pass something indescribably horrific. That’s no visage of dark, forbidden knowledge; you know as well as I do that everyone used to look that miserable in posed portraits. No, I mean, really look at this person, this jittery guy, this emotionally backward genius man-child whose parents stuck him with an extra helping of weird right off the bat. His mom neurotically coddled him into a lifelong hypochondria; his dad, afflicted with syphilis-fueled psychosis, died in an asylum when Howard was 8; the kid seems to have suffered from awful, hallucinatory night terrors through childhood. This fiercely intelligent boy, nervous and awkward, sat down at the bookshelf and became a voracious reader, diving into the much more controllable worlds of fiction and science, finding magic in the stories of imaginary and incredible far-off places.

I propose we step away from the iconic figure of H.P. Lovecraft, originator of cosmic horror, genre author of the century. Instead… take a look at plain old Howard Lovecraft, skinny dude from Rhode Island. Go on, look at him. And don’t just look at that one headshot, either, where he’s grimacing past the camera like he’s on the toilet trying to pass something indescribably horrific. That’s no visage of dark, forbidden knowledge; you know as well as I do that everyone used to look that miserable in posed portraits. No, I mean, really look at this person, this jittery guy, this emotionally backward genius man-child whose parents stuck him with an extra helping of weird right off the bat. His mom neurotically coddled him into a lifelong hypochondria; his dad, afflicted with syphilis-fueled psychosis, died in an asylum when Howard was 8; the kid seems to have suffered from awful, hallucinatory night terrors through childhood. This fiercely intelligent boy, nervous and awkward, sat down at the bookshelf and became a voracious reader, diving into the much more controllable worlds of fiction and science, finding magic in the stories of imaginary and incredible far-off places.

Hmmm.

Our young friend Howard P. adored the fantasy stories of Lord Dunsany and the horror stories of Edgar Allan Poe. Adored. Utterly. He spent at least half his literary life emulating the styles of his two idols before he finally settled into his own adult voice; he didn’t hesitate to acknowledge that “The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath” was his Dunsanian epic and tales like “The Outsider” were practically Poe fanfic. That’s right: Howard Lovecraft was a total fanboy, and he got hotter than ever for Dunsany after seeing him give a live talk. If there’d been a World Fantasy Convention or a DragonCon in the 1910s or ’20s, the gawky stringbean from Rhode Island wouldn’t just have attended, he would have followed poor Lord Dunsany around all weekend and asked him questions after every. single. panel. The guy loved his storytelling heroes, and that love still resonates in the way he assimilated their artistic strengths into his own.

You know what else still resonates? The passion with which Howard Lovecraft strip-mined his own youthful games and obsessions to create his more mature stories. As a kid, after reading the Arabian Nights, he dubbed himself “Abdul Alhazred,” a made-up Arabian-sounding name. Years later, he’d hand that persona over to one of his most important characters: in the Cthulhu mythos, it is the mad poet Alhazred who pens the tome of ultimate evil known as the Necronomicon. So, in effect―wait, can this be right?―young Mr. Lovecraft basically took his old roleplaying character and Mary-Sued him right into a destiny as the most powerful author in the world.

Wow. That is geeky. And I don’t mean pseudo-geeky or a historical predecessor to geeky, I mean that is seriously geeky, like the writing your own Doctor Who story where the Doctor regenerates into YOU kind of geeky.

Of course, you might argue that Alhazred, whose creation of the Necronomicon ultimately leads to his torture, blindness, and insanity, isn’t much of a wish-fulfillment character. And you’d be right, except you’re forgetting that this kid Howard Lovecraft was one morbid freaking puppy. Why not imagine himself as a tormented but at least potent madman? Sickly, jumpy, weighed down by a dead-via-syphilitically-insane father, rather repulsed by the idea of sexual romance (hard to imagine why), had a nervous breakdown toward the end of his senior year in high school and never actually got his diploma despite being a whiz kid prodigy ― this is the guy who dreamed up a giant winged tentacled alien buried for millennia beneath the earth that would someday wake up and devour all mankind in an orgy of destruction representative of the vast Einsteinian universe’s oblivious and infinite disregard for something as utterly meaningless as human life.

I mean, Jesus. Emo much? The Beats and the Goths and Hamlet all gathered in a black room together couldn’t have out-moped this cosmic-scaled portrait of gloom if they’d tried. That is some epic creative pouting right there.

All this, I submit, adds up to our answer. Why is H.P. Lovecraft still stirring the imaginations of young fans today who’ve already been weaned on the exciting tales written by his flashier, snappier offspring? And this despite the fact that, hey, the guy had a positively obsessive fixation on the idea of racial purity, which you’d think would make his writing totally unpalatable today and yet, somehow, doesn’t?

It’s because all us fantasy-horror-SF-whatever nerds recognize ourselves in these old stories. Howard Lovecraft, the over-brained weirdo who lived with his mom―he was us… first. Geek Prime. Fanboy Alpha. The Original Emo Kid. And he oozed it all over every page.

And we just can’t help loving him for it.

Read more Lovecraft on Tor.com!

Stephen H. Segal is the editorial and creative director of Weird Tales and a book designer who has worked with Tor Books, Juno Books, Prime Books, the Interstitial Arts Foundation, and others. He has previously served as a magazine editor at WQED Pittsburgh, a publication consultant for Carnegie Mellon, and a writer for the Philadelphia Weekly newspaper chain.