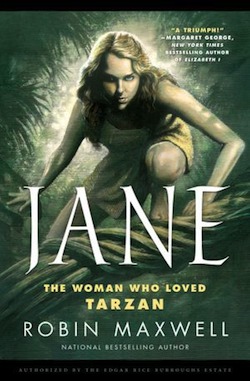

This year marks Tarzan’s 100th anniversary, and we have just the book for it — take a look at Jane: The Woman Who Loved Tarzan by Robin Maxwell, out on September 18:

Cambridge, England, 1905. Jane Porter is hardly a typical woman of her time. The only female student in Cambridge University’s medical program, she is far more comfortable in a lab coat dissecting corpses than she is in a corset and gown sipping afternoon tea. A budding paleoanthropologist, Jane dreams of traveling the globe in search of fossils that will prove the evolutionary theories of her scientific hero, Charles Darwin.

When dashing American explorer Ral Conrath invites Jane and her father to join an expedition deep into West Africa, she can hardly believe her luck. Africa is every bit as exotic and fascinating as she has always imagined, but Jane quickly learns that the lush jungle is full of secrets—and so is Ral Conrath. When danger strikes, Jane finds her hero, the key to humanity’s past, and an all-consuming love in one extraordinary man: Tarzan of the Apes.

Jane is the first version of the Tarzan story written by a woman and authorized by the Edgar Rice Burroughs estate. Its publication marks the centennial of the original Tarzan of the Apes.

Chicago Public Library, April 1912

Good Lord, she was magnificent! Edgar thought. Infuriatingly bold. He had many times fantasized about women such as this Jane Porter, but he honestly believed they existed only in his imagination. The vicious heckling she had endured for the past hour in the darkened room would have broken the strongest of men, yet there she stood at the podium casting a shadow on the startling image projected by the whirring episcope on the screen behind her, back straight as a rod, head high, trying to bring order back into the hall.

Her age was indeterminate—somewhere approaching thirty, but her presence was one of striking vitality and self-assurance. She was tall and slender beneath the knee-length suit coat of fine brown wool. Her honey-colored hair was tucked up beneath a simple toque of black felt, not one of those large frivolous feathered creations that these days hung perilously cantilevered over a woman’s face. Emma wished desperately for one of those freakish hats, and Edgar was secretly glad they were still too poor to afford it.

“These claims are preposterous!” cried a man seated halfway back in the crowded room. He had the look of an academic, Edgar thought.

“These are not claims, sir. They are the facts as I know them, and physical evidence, here, right before your eyes.” There were hoots of derision at that, and catcalls, and Jane Porter’s chin jutted an inch higher.

“This is clearly a hoax,” announced a portly bearded man who brazenly walked to the table in front of the podium and swept his hand above the massive skeleton displayed on it. “And a bad hoax at that. Why, you haven’t even tried to make the bones look old.”

The audience erupted in laughter, but the woman spoke over the commotion in a cultured British accent with more equanimity than Edgar thought humanly possible.

“That is because they are not old. I thought I made it clear that the bones came from a recently dead specimen.”

“From a living missing link species,” called out another skeptic. The words as they were spoken were meant to sound ridiculous.

“All you’ve made clear to us today, Miss Porter, is that you should be locked up!”

“Can we have the next image, please?” the woman called to the episcope operator.

“I’ve had enough of this claptrap,” muttered the man sitting just in front of Edgar. He took the arm of his female companion, who herself was shaking her head indignantly, and they rose from their seats, pushing down the row to the side aisle.

This first defection was all it took for others to follow suit. Within moments a mass exodus was under way, a loud and boisterous one with rude epithets shouted out as hundreds of backs were turned on the stoic presenter.

Edgar remained seated. When someone threw on the electric lights, he could see that the episcope operator up front in the center aisle was wordlessly packing up the mechanism of prisms, mirrors, and lenses that threw opaque images onto the screen as the speaker began her own packing up.

Finally Edgar stood and moved down the side aisle to the front of the meeting hall. He rolled the brim of his hat around in his hands as he approached Jane Porter. Now he could see how pretty she was. Not flamboyantly so, but lovely, with an arrangement of features— some perfect, like her green almond eyes and plump upward-bowed lips, and some less so, like her nose, just a tad too long and with a small bump in it—that made her unique.

She was handling the bones as if they were made of Venetian glass, taking up the skull, shoulders, arms, and spine and laying them carefully into a perfectly molded satin receptacle in a long leather case.

She looked up once and gave him a friendly, close-lipped smile, but when he did not speak she went back wordlessly to her task. Now it was the lower extremities that she tucked lovingly away, using special care to push the strange big-toe digits into narrow depressions perpendicular to the feet.

Edgar felt unaccountably shy. “Can I give you a hand?”

“No, thank you. They all fit just so, and I’ve had quite a lot of practice. London, Paris, Moscow, Berlin.”

“I have to tell you that I was completely enthralled by your presentation.”

She looked at Edgar with surprised amusement. “You don’t think I should be locked up?”

“No, quite the contrary.”

“Then you cannot possibly be a scientist.”

“No, no, I’m a writer.” He found himself sticking out his hand to her as though she were a man. “The name’s Ed Burroughs.”

She took it and gave him a firm shake. He noticed that her fingernails were pink and clean but altogether unmanicured, bearing no colorful Cutex “nail polish,” the newest rage that Emma and all her friends had taken to wearing. These were not the hands of a lady, but there was something unmistakably ladylike about her.

“What do you write, Mr. Burroughs?”

He felt himself blushing a bit as he pulled the rolled-up magazine from his jacket pocket. He spread it out on the table for her to see. “My literary debut of two months ago,” he said, unsure if he was proud or mortified.

“All-Story magazine?”

“Pulp fiction.” He flipped through the pages. “This is the first installment in the series I wrote. There was a second in March. My pen name’s Norman Bean. It’s called ‘Under the Moons of Mars.’ About a Confederate gentleman, John Carter, who falls asleep in an Arizona cave and wakes up on Mars. There he finds four-armed green warriors who’ve kidnapped ‘the Princess of Helium,’ Dejah Thoris. He rescues her, of course.”

She studied the simple illustration the publisher had had drawn for the story, something that’d pleased Edgar very much.

“It really is fiction,” she observed.

“Fiction, fantasy . . .” He sensed that the woman took him seriously, and he felt suddenly at ease. It was as if he had always known her, or should have known her. She exuded something raw and yet something exceedingly elegant.

“When I was ten I came home from school one day and told my father I’d seen a cow up a tree,” Edgar said, startling himself with his candor with a complete stranger. “I think I said it was a purple cow. I was punished quite severely for lying, but nothing stops a compulsion, does it?” When she shook her head knowingly, he felt encouraged. “A few years later I moved to my brother’s ranch in Idaho and stayed for the summer. By the time I was enrolled at Phillips Academy I could spin a pretty good yarn about all the range wars I’d fought in, the horse thieves, murderers, and bad men that I’d had run-ins with. It was a good thing my father never heard about them.”

A slow smile spread across Jane Porter’s features. “Well, you’ve shown him now, haven’t you. A published author.”

“I’m afraid my old man has yet to be convinced of my myriad talents.”

She snapped both cases closed and took one in each hand.

“Here, let me help you with those.”

“No, thank you. Having the two of them balances me out.”

“I was hoping you’d let me take you out to dinner. Uh, I’d like very much to hear more about your ape-man.”

She stopped and looked at him. “Honestly?”

“Yes.”

“You must pardon my suspiciousness. I have been booed and hissed out of almost every hallowed hall of learning in the world. This is the last. I tried to have my paper heard at the Northwestern and Chicago universities, but I’m afraid my reputation preceded me and they said absolutely not. That’s why you had to listen to my presentation at a meeting room at the Chicago Public Library.”

“So will you come out with me?”

The woman thought about it for a very long moment. She set down her cases and walked to the man at the episcope, quietly conferred with him, and returned. “It’s really not a good idea for us to talk in public, but my hotel is nearby. You and I can go up to my room.”

“I wouldn’t do that if I were you,” Edgar said. “Chicago police keep an eye on even the nicest hotels. They might arrest you for soliciting. But my apartment’s not too far. The wife and kids have gone to her mother’s for the weekend. I mean . . . sorry, that sounds . . .”

“Mr. Burroughs, your apartment’s a fine idea. I’m not afraid of you. But don’t you care about the neighbors?”

He eyed the woman’s bulky luggage. “I’ll tell them you’re selling vacuum cleaners.”

She smiled broadly. “That will do.”

They were largely silent on the taxi ride across town to his Harris Street walk-up, except for the exchange of pleasantries about the lovely spring weather they were having and how April was almost always horrible in England.

It was just Edgar’s rotten luck that the only neighbor who saw them come in was the landlord, a petty, peevish little man who was looking for the rent, now more than a week late. Edgar was relieved to get Jane Porter up the three flights and inside, shutting the door behind them, but he cringed to see the empty cereal bowl and box of Grape-Nuts that he’d left on his writing desk. There was a pile of typewritten pages on letterhead lifted from the supply closet of the pencil sharpener company he worked for, a mass of cross-outs and arrows from here to there, scribbled notes to himself in both margins.

“It’s a novel I’m writing, or should say rewriting . . . for the third time. I call it The Outlaw of Torn.” Edgar grabbed the bowl and cereal box and started for the kitchen. “I turn into a bit of a bachelor when my wife is away. By that I don’t mean . . .”

“It’s all right,” she called after him. “You have children?”

“A boy and girl, two and three. Why don’t you sit down? Can I get you something to drink? Tea? A glass of sherry?”

“Yes, thank you. I’ll have a cup of water. Cool, please.”

When Edgar returned from the kitchen, his guest was sitting at the end of the divan in an easy pose, her back against the rounded arm, her head leaning lazily on her hand. She had taken off her suit coat, and now he could see she wore no stiff stays under the white silk blouse, those torturous undergarments that mutilated a woman’s natural curves. She wore no jewelry save a filigreed gold locket hanging between shapely breasts, and it was only when she was opening the second of the two cases holding the skeleton that he saw she wore a simple gold wedding band. He could see now where she had meticulously pieced together the shattered bones of the apelike face.

He set the water down and sat across from her. Now she sighed deeply.

“Are you sure you want to do this?” Edgar asked, praying silently that she did.

“Well, I’ve never told this in its entirety. The academics don’t wish to hear it. But perhaps your ‘pulp fiction’ readers will. I can tell you it’s a story of our world—a true story, one that will rival your John Carter of Mars.”

“Is it about you?”

“A good part of it is.”

“Does what happened to you in the story explain your fearlessness?”

“I told you, I’m not frightened of you. I . . .”

“I don’t mean me. You took an awful lot of punishment this afternoon . . . and in public, too. You’re a better man than I.”

She found Edgar’s remark humorous but grew serious as she contemplated his question. “I suppose they did toughen me up, my experiences.” She stared down at her controversial find, and he saw her eyes soften as though images were coming into focus there.

“Where does it begin?” he asked.

“Well, that depends upon when I begin. As I’ve said, I’ve never told it before, all of it.” She did some figuring in her head. “Let me start in West Central Africa, seven years ago.”

“Africa!” Edgar liked this story already. Nowhere on earth was a darker, more violent or mysterious place. There were to be found cannibals, swarthy Arab slave traders, and a mad European king who had slaughtered millions of natives.

“It just as well could start in England, at Cambridge, half a year before that.” She smiled at Edgar. “But I can see you like the sound of Africa. So, if you don’t mind me jumping around a bit . . .”

“Any way you like it,” Edgar said. “But I know what you mean. It’s not easy figuring out how to begin a story. For me it’s the hardest part.”

“Well then . . . picture if you will a forest of colossal trees. High in the fork of a fig, a great nest has been built. In it lies a young woman moaning and delirious. Her body is badly bruised and torn.”

“Is it you?” Edgar asked.

Jane Porter nodded.

“I have it in my mind. I can see it very well.” Edgar could feel his heart thumping with anticipation. He allowed his eyes to close. “Please, Miss Porter . . .” There was a hint of begging in his voice. “Will you go on?”

July 1905

It was the hurt that woke me—white-hot needles at shoulder and calf, and deep spasms the width and length of my back. My head throbbed. Fever seared. Limbs like lead. Bright patterns dancing behind closed lids. Too much effort to move a finger, a toe. Frightening. Did I have the strength to open my eyes? And what was the cause of my agony? What had happened? Where was I? Then I remembered. Recalled the last sensation that was pure terror made corporeal.

I was a leopard’s next meal.

Why was I not dead? Was I even now in the cat’s lair? Would I open my eyes to a pile of bones and rotting corpses of its earlier prey? Was the cat waiting an arm’s length away to finish me?

No. Beneath me was softness. My arms and legs were gently positioned and cushioned. But this was not a bed. The air was fresh, fragrant. I was outdoors. I could make no sense of it. I strained to remember. Called out for help.

I dared to hope.

“Father?” My voice was so weak. How would he ever hear me? I drew a long breath to give me strength, but that small act was a knife to my ribs. I fought to raise my lids, but the minuscule muscles defied me.

“Fah-thah.” It was a male voice, deep and resonant, even in its youth. Fevered as I was, a chill ran through me.

Who was this stranger? Dare I speak again?

A wave of pain assailed me and crushed the words into meaningless cries and moans. I was so weak, buffeted, helpless in a sea of suffering. Then two strong, comfortable arms cradled me, lifted me tenderly, held me to a broad male breast as a father would a small, ailing child.

Relief flooded me and I sank gratefully into my protector’s chest. The skin was smooth and hairless, the scent richly masculine. The throbbing heartbeat against my ear was strong and I heard the mindless humming, a familiar lullaby. I was rocked so gently that I fell into a swoon of safe repose.

How long it was before I awoke again I did not know. But with the pain having substantially subsided, when I opened my eyes this time I could see very clearly indeed, and my mind had regained sense and order.

I was in the crook of a tree where four stout limbs came together, lying on a thick bed of moss. I saw the naked, heavily muscled back of the man I remembered only for his fatherly embrace. He squatted beside me in what could rightly be called a “nest.” His skin was mildly tanned, marred only by several fresh scratches and puncture wounds, the hair a matted black mass hanging down below his shoulders.

When he turned, he was spitting a just-chewed blue-green substance from his mouth into his hand, and was as startled at my waking state as I was at the entirety of him.

We were equally speechless. He never took his eyes from me as he finished chewing, then spat the rest of the paste into his palm. I lifted onto my elbows but winced at the pain this caused my left shoulder. I turned my head and saw the appalling injury—four deep gouges in the flesh.

He gently pushed me down and began to pack the green substance into the wounds. His ministrations were straightforward, and in the silence as he tended the shoulder scratches and another set on the back of my right calf, I gazed steadily at his face, overcome with a sense of wonder and unutterable confusion.

He was the most beautiful man I had ever seen. Perhaps twenty, he was oddly hairless on his cheeks, chin, and under his nose, with only a soft patch at the center of his chest. The face was rectangular with a sharp-angled jaw, the eyes grey and widely set, and alive with intensity and inquisitiveness. Jet-black brows matched the unruly mane.

Though a stranger and clearly a savage, he touched me intimately, but he did so unreservedly, like a workman at his job, and I felt no compulsion to recoil from that touch.

Then he did the strangest thing. He raised his hand to my face and, turning the palm up, laid the back of it on my forehead, as a mother would to her child to check for fever. I thought I detected satisfaction in what he’d found, and indeed, I felt the fever had gone from my body.

Now he met my gaze and held it with terrible intensity. His lips twitched for several moments before any sound emerged. Then finally he spoke.

“Fah-thah,” he said.

“Fah-thah?” I repeated. Then understood. “Father.”

The sound of the word and the thoughts it evoked suddenly tore through my being and, lacking all restraint, I began to wail. Where was my father? Was he alive or dead? Did he have any knowledge of my whereabouts?

Everything in me hurt, but most of all my heart.

The young man moved to take me into his arms as he’d done before, but now I began to struggle, pushing him away, crying out with pain of my torn shoulder and thoughts of my father. With a stern countenance, the man opened his palms and, spreading them across my chest, pushed me back down in the moss.

My face and body went slack in surprise, and I ceased struggling. He withdrew his hands and in time I calmed. I never took my eyes from him. Now I placed my own hand on my chest and spoke again.

“Jane,” I said.

He was silent, eyeing me closely.

“Jane,” I repeated, this time tapping my chest.

Understanding glittered in his eyes.

“Jane,” he said.

I refused to give in to false or premature hope, but I rewarded his victory with a small smile.

He grew excited. He tapped his own chest and said, “Tarzan.” So this was his name? Odd. Tarzan. He placed his hand over my hand, then said his name once more.

But I shook my head and finally said “no.”

He nodded his head yes. “Tarzan. Tarzan,” he repeated.

I laid my head back, closing my eyes and sighing deeply. I wanted to shout, “No, I am not Tarzan. You are Tarzan!” But I must be patient.

And then very suddenly, as though he, too, was spent from the frustrating conversation, he left me and climbed from the nest, disappearing from my sight.

I lay there alone, trying to order my mind. There had been a brief moment when I thought the savage might possess intellect, and my heart had soared. He was able to mimic words. I must have uttered “Father” in my delirium, and he’d remembered it. And he had repeated “Jane” instantly and clearly, and even appeared to understand that this was who I was. And then . . . oh, I grew heavy with disappointment—he had called us both by the same strange name: Tarzan. He was clearly an imbecile, a feral child, grown up. A freak of nature. And while he was at least gentle and had nursed me so carefully, I despaired that this creature was the one and only key to my salvation, if that was in fact a possibility.

Now that he was absent from the nest, I gazed around. It was a rough home to be sure, but a home all the same. I saw a depression in the moss beside where I lay—long and deep. It was clearly where the tameless man had been sleeping—so close to me. There were few artifacts. A stone-tipped spear. Near my head a pair of half coconut shells, and next to them a pith helmet—my own?—all of them filled with clear water.

But where was I?

I looked up and around me. I recognized the tree as a fig, and a large one at that.

It seemed that this nest was quite high off the ground. How on earth had I gotten here? Certainly it was by virtue of the gentle savage, but I had been injured. As a deadweight, I’d been carried up a tree!

Although every movement was still an agony, my mind was clearing moment by moment. But still I found myself tumbling fearfully in an avalanche of questions.

How serious were my injuries? Will I live or die? Where was my father? We had come together into this forest. Was he even alive? Deathly ill? What has he been told about my whereabouts? Was he searching for me even now? And who or what, in heaven’s name, was this man . . . my savior?

Then suddenly, unaccountably, the pain subsided like an outgoing tide. I found myself soothed, lulled into comfort by the sounds and the scents around me. It was an incessant thrum—trilling, piping, and whistling of birdsong. Calls and answers. Clicking and chip-chipping of insects. The rumbling roar of a distant waterfall.

I should think! Plan! But I could not. The sudden absence of pain, the delicious stillness of my body, the comfort of the bed, the sweet and pungent fragrances and the sounds. Oh, the sounds made me lazy, indolent. I allowed my mind to drift. Not like me. Not like me at all. Always too busy. So much to accomplish. So much to prove. Here there was no accomplishing. Here there was only being, and gratitude that I was alive and safe and not a leopard’s dinner . . .

Only then did I think to look down at my body. My left shoulder was bare—the sleeve from my bush jacket gone. The terrible wound packed with green-blue paste no longer throbbed. Was it this strange medicine that relieved the pain? The rest of my jacket, I could see, covered me, but the front—still buttoned—was lying atop my chest like a small blanket. I felt with my right hand. The jacket’s back was beneath me, the two parts unattached, the seams apparently ripped apart.

I needed to lift my head to observe my lower body, but the spasm that racked my neck and back with even the smallest movement forced a speedy look. It revealed a similar configuration. The lower right trouser leg was gone. A dull ache in my right calf reminded me of the claw wounds there and the blue-green poultice that packed it. The front of my trousers loosely covered my bottom half, and I assumed the backs were underneath my buttocks and legs.

The thought struck me that such an arrangement of my clothing had to have been accomplished by my new friend, and I wondered at his inventiveness. Would an imbecile have achieved so ingenious a sickbed? He had applied medicine that appeared to have prevented infection of my wounds, ones that while severe showed neither redness nor swelling nor suppuration, and provided substantial analgesia.

How long had I been unconscious? I realized with horror that my modesty must certainly have been compromised. What of my bodily functions? I felt clean and dry below, and detected no unsavory odors from my nether regions. Stop! I ordered myself. The accomplishment of urination and defecation in the presence and with the help of a strange male was certainly an embarrassment, but it was far from my greatest concern.

Suddenly a tight packet of leaves plopped down on the opposite side of the nest and a moment later came the man, leaping with utter grace and agility up over its side. Thankfully, his private parts were covered with a loincloth of sorts, really just a short animal skin tied at the waist covering the front of him, with what appeared as the wooden hilt of a large weapon protruding across his taut, rippling belly. His long legs were exquisitely muscled, as were his buttocks, and even his feet, bare of coverings of any kind, possessed great definition and obvious strength. As he came close and squatted unselfconsciously beside me, I thought that the sinuous toes, flexible and as powerful as fingers, were much like an ape’s—good for climbing.

He held my gaze, seeming pleased at the clarity he saw in my eyes, and spoke.

“Tarzan,” he uttered with great certainty.

All right, I thought, he is not an imbecile. We have simply not learned proper communication with each other. I touched the center of my chest lightly with my right hand.

“Jane,” I said and nodded my head, smiling. I touched my breastbone again. “Tarzan . . .” I shook my head with definitive negativity and frowned.

His expression was at first quizzical. Then he smiled. He tapped my chest lightly. “Jane,” he said. Then he tapped his own. “Tarzan.”

He understood!

I returned the smile to encourage him, though to be honest, my smile was entirely sincere. There was hope to communicate with this creature. No, I corrected myself. Not a creature. A man.

And a beautiful one at that.

I lay still and quiet as he opened the banana leaf he had tied up with thin vine and revealed inside it wood mold and nuts, and the fruit of the pawpaw tree.

He first applied the delicate fuzz to my wound, and the moist paste caused it to disappear. Then he grabbed the flat rock from the nest’s rim and, pulling out his blade, broke the nuts’ shells with the hard handle. He offered the nut meat to me in the palm of his hand. Yet I did not take or eat them. I was staring hard at the blade.

He held it out flat in front of me to see.

“Boi-ee,” he said proudly.

“Bowie?” I said, astonished. What was this man, this “Tarzan,” doing with a Bowie knife, and how on earth did he know its proper name? My father had such a blade in his collection of weapons. I had heard the story of Jim Bowie, the frontiersman who had died at the American Battle of the Alamo and had given the famous knife its name. There was nothing else about the man squatting beside me, or his home, that remotely bespoke of the civilized world.

And suddenly a Bowie knife.

This was a mystery, but perhaps more confounding was my trust in the man—Tarzan. I’d not questioned the grey mold he had rubbed into the poultices on my shoulder and calf, but I somehow assumed that it would improve my condition. How had I come to trust this wild man, a being whose life and mind were becoming more bewildering to me with every passing moment?

He again extended his hand holding the nuts, and though I felt no hunger I was moved to accept them. It was a token of faith and friendship. Indeed, he seemed pleased when I put them in my mouth and chewed. He smiled and went to work peeling the pawpaw, gutting it of its black seeds.

When he held out a portion to me—the simple sharing of food between members of a family—I wondered how it had come to this so very quickly.

I brought the yellow fruit to my lips and took a bite. Nothing I had tasted in my life, I thought, had ever been so sweet.

Together we quickly devoured the meal, and when he rose again, I knew that he was off to gather more. As he stood on the lip of the nest preparing to slide the Bowie knife into its sheath, a rare ray of sunlight pierced the thick canopy above to glint blindingly off the blade. I closed my eyes and saw . . .

. . . reflected January sunlight glittering off the razor-edged scalpel in its small wooden chest. The sight of the serrated bone saw, knives and drills and probes with their ebonized handles filled me with satisfaction. My very own dissection kit.

Yet standing there alone in the bright high-ceilinged chamber with two rows of sheet-draped cadavers—alone if one did not count the bodies of the deceased—I could feel a nervous flutter in my chest. The sickly sweet and acrid smell of formaldehyde, and the flesh it prevented from putrefying, stung my nose. Get your bearings, girl. You’re in the gross-anatomy laboratory at Cambridge. No time for floundering!

The medical students would be arriving any moment. Would it be the jocular, shoulder-bumping playfulness that I saw in the lecture hall, courts, and arches, I wondered, or would they quiet and grow still in this strange sepulcher?

There was a clattering at the door as a laboratory servant, his arms piled with tin pails, hurried in and began placing one at the foot of every table, for discarded parts I guessed.

I recognized the young man, Mr. Shaw, a graduate of the medical college who had yet to find a position in the world. The professor of human anatomy had happily taken him on to this posting that was both lowly in its tasks and most necessary to the smooth functioning of the laboratory. Servants, though they were called, were valued very highly, and the best of them, like Mr. Shaw, fetched and carried and mounted specimens that were produced by the students’ work. Some servants were paid as much for their services as college lecturers.

“Your first day, Miss Porter?” Shaw inquired.

I nodded.

“Make sure you keep the face covered,” he said of the corpses. “That’s the bit that can give you a nasty shock. My first day the towel fell off and I found myself staring at a granny with half of her skin flayed down to the muscle and an eyeball hanging down by the optic nerve. I retched into one of these buckets every few minutes till the end of the session.” He set down one of the pails near my feet. “Apparently it was a record-breaking spew . . . my classmates never let me forget it.”

“I’ll take your advice, Mr. Shaw. I’ll wait a bit to uncover the face.”

“Good luck to you, miss.”

The laboratory was filling with young men, two to a table. Presently one of them took his place across from me. He was a freshfaced boy with skin so pale and translucent that blue veins formed a delicate map across his cheeks and forehead.

“I’m Woodley,” he said. “You’re Jane Porter.”

I could hear snickering from the tables on either side of us and the row across the aisle. I’d prepared myself for all manner of derision. The first woman to gain entry into this hallowed laboratory was sure to stir controversy and even indignation. I have every right to be here, I repeated to myself for the hundredth time that day and almost unconsciously pulled back my shoulders and thrust out my chin.

The movements, subtle as they were, did not go unnoticed by a too-handsome young man I knew from the anatomy lecture hall. Arthur Cartwright’s family was old, and they had managed to preserve their wealth and prestige in the previous century that had seen so many of them collapse into genteel poverty. Cartwright wore his arrogance like a badge of honor. All he did was smirk at me.

“Shall we?” Woodley asked.

Leaving the face covered with a small towel, Woodley pulled the sheet away, revealing what looked to be a middle-aged man. It was already a partly dissected cadaver, as I had joined the class in the middle of its term. I could see that the skin of one forearm had been peeled away, revealing musculature that looked decidedly like the stringy meat on a dried-out turkey carcass. A large opening in the abdomen exposed the intestines and multitudinous folds of the mesentery tissue. A repulsive odor wafted up from the belly and hit me with a force that knocked me back on my feet.

“I know,” said Woodley. “The gut stinks far worse than the rest. You’ll get used to it. Or you won’t.”

I was aware that even though work had begun on all the tables around mine and Woodley’s, everything that was being said here, and probably my reel backward from the odor of the abdominal cavity, was being closely observed by Cartwright and the others. They were all most certainly waiting for an opportunity to chime in with a barb, a pun, or their idea of a witty rejoinder . . . at my expense, of course.

“Mr. Woodley,” said Cartwright in a most unctuous tone, “perhaps you should help Miss Porter with the dissection of the rectum.”

I thought how apropos was my fellow student’s choice of body parts, as that was the precise orifice I’d just silently affirmed I would associate with Arthur Cartwright for the rest of my days.

But what I said aloud was, “Thank you, but I can take care of myself very well.”

“I’m quite sure you can.” The five words were spoken by Cartwright with such lewd innuendo that his corner of the laboratory erupted with laughter.

I gathered my wits and fixed my eyes on the flayed corpse. In the most demure tone I could summon, I said, “Mr. Woodley, might you show me this man’s testicles?”

There were roars of laughter, hoots and howls. Not a full minute had passed before the professor of anatomy, the most revered of lecturers, was in our midst. He was a clean-shaven man, and his barrel chest lent power to his otherwise tall, rangy appearance.

“Gentlemen!” The single word was close to a shout, and he spoke it with blatant irony. These were ruffians he was addressing, his tone revealed—anything but well-bred university men. The professor’s usual good nature and easy manner had vanished. His Midwest American twang seethed with gravitas as he continued. “You are working on human cadavers that were once living, breathing men and women. Somebody’s father, mother, child. It is the reason that we in the dissection room wear black coats, not the white of scientists and physicians—out of respect for the dead. There will be no laughter in the anatomy laboratory. No horseplay. Ever. Now get on with it.”

In that moment, the silence of the dead filled the room, and the students returned, chastened, to their grisly business.

I felt the professor looming above me, He whispered into my ear, “You should have known better.”

I turned and spoke so softly I doubted Woodley, across the table, could hear. “Sorry, Father. You may come to regret the mountains you moved to get me into this classroom.”

“I’ll be the judge of that,” he said and, moving away, called over his shoulder, “Button up that coat, Mr. Cartwright. You look like a trash collector.”

I returned my eyes to the cadaver.

Woodley addressed me with mock dignity. “Was it the testicles you wished to be shown, Miss Porter? Or the scrotal sac?”

“Neither, Mr. Woodley. I think I’ll investigate the larynx.”

I felt his eyes on me as I removed the smallest of the scalpels from the instrument kit and attempted to make my first incision, this to remove the skin in the center anterior of the neck. Nothing happened under the knife.

“The human hide is tougher than you think,” Woodley told me. “Pressure should be firm, but not so firm as to slice through any more than the derma. Think of cutting into an overcooked heel of roast beef.”

I tried again. To my delight, the bloodless flesh parted. Having exposed what lay beneath, I closed my eyes and recalled what I had studied so carefully in my anatomy text.

“I had the larynx last term,” Woodley said. “Remove the mucous membrane posteriorly to expose the laryngeal muscles and the inferior laryngeal nerve. Then you can remove the lamina of the thyroid cartilage on one side to view the remaining laryngeal muscles.”

I thanked him and set to work carefully and assiduously in the soft tissue. I found myself handling the new knives and probes with unexpected dexterity. It was as though I had used the tools all my life. Nothing was so sublime or miraculous as the human body. So many secrets buried in flesh and bone.

Ah, there they were, the vocal cords!

I paused, awestruck, as a treasure hunter would before opening a long-lost cask of golden coins. I was startled when Woodley spoke again.

“You seem to know what you’re looking for in there.”

“Are you familiar with Dubois’s paper on the development and evolution of the larynx? That the mammalian larynx issues from the fourth and fifth branchial arches of the embryo, implying,” I continued, perhaps too zealously, “that the human voice box evolved from the gill cartilage of fish? Those structures that once filtered oxygen from water now filter air . . . and make sound!” I remembered then that I ought to keep my voice down.

“Ah, this is what all the excitement is about,” Woodley said. “Dubois’s ‘missing link.’ His ‘Java man’ fragments.”

“I’d say they’re rather more than fragments. A tooth. A thighbone . . . and a complete skullcap.”

“It hasn’t been proved that they’ve come from the same individual.”

“Rubbish! They were found at the same depth, and only fifteen yards away from each other. Their color and texture are identical.”

Woodley never took his eyes from the long, ropy intestines he had extracted from the cadaver and placed for examination on its still-intact chest.

“Well,” I demanded, “do you have an opinion on it?”

“Not really. I’m studying to be a physician, not a fossil hunter.”

“Certainly you have an opinion on so important a scientific question.”

“It’s important to some people.”

“Some people?” I was incensed. “So you don’t care whether your forebearers were ape-men, or creatures that came magically out of Adam’s rib?”

Woodley was clearly unused to such a highly opinionated lady.

“The apes, I suppose,” he finally muttered.

Truly, I would have been shocked had he chosen the rib. Few educated men and women denied Darwin, but fewer still were courageous—or some said idiotic—enough to make paleoanthropology their career. In other than the scholarly crowd, such a calling was laughable. This was a contradiction that drove me mad.

“Are you coming to hear Dubois at the congress?” I asked.

“The congress?”

“The International Congress of Zoology. He’s presenting his Java man finds here, later this month. Are you coming?”

“Are you?”

“Oh, Mr. Woodley. I really hope you’re not the type who’s always answering a question with a question.”

He gave me a sharp look. “I’m trying to like you, Miss Porter. You make it very difficult.”

Aware that my impatience was getting the better of me, I resumed my dissection. “Yes, I’m going. My father and Eugène Dubois are friends. But you knew that.”

“Everyone knows that.” There was a strained silence. “Miss Porter . . .”

“What?”

“Be careful with the vocal folds. They’re very delicate.”

“Thank you,” I said, contrite. Perhaps Woodley was a decent sort of man after all. There were so many I would just as soon send to the bottom of the ocean. I looked up and managed a smile. “Can you tell me which tool you suggest?”

Unladylike though it was, I dashed across the Newnham College green clutching my valise in one hand, hat to my head with the other. The scarf ties flew out behind like wind-whipped banners, and the young women walking two by two with great decorum skewered me with the evil eye. But my father was waiting just beyond the hedge in the Packard, eager to make an end to his week’s work at the university. And I hated to keep him waiting.

As many weekends as I was able, I went home with the professor. I lived for these times, working with him in the manor laboratory and keeping company with my animals. The courses at Newnham— one of the two women’s colleges at Cambridge—were adequate, and I appreciated the extreme privilege of participating in higher education, but the restrictions imposed upon my sex irked me beyond measure. Women could attend classes at Cambridge and write examinations. But Newnham had its own library and separate laboratories, as girls were prohibited from sullying those hallowed halls in the men’s colleges. Worst of all, females could not graduate or qualify for a degree of any kind. It was maddening!

That was why my admission into the anatomy laboratory—the only one at Cambridge—had been such an unimaginable coup. Certainly it had stirred numerous debates and ruffled whole hatsful of feathers, even prompting several of the fellows to suggest my father’s termination as a lecturer.

But to hell with them! None of the other girls at Newnham had a fraction of the ambition that I did. I was going to make something of myself. Leave a mark on the world. And that was that.

It had been my great good fortune to have a champion for a father—one who so openly applauded my audacity and who, in every way within his power, was clearing the path for my success.

As I came around the high hedge, I heard the Packard running before I saw Father—Professor Archimedes Phinneaus Porter— behind the wheel of his pride and joy—the bright blue two-seater Mother had recently given him for his fiftieth birthday. I smiled whenever I thought of my father thusly. “Archie” was what he called himself, undistinguished as that might sound. He’d never forgiven his parents for saddling him with such a ridiculously antiquated name, which was why, he explained, he had given his daughter such a plain one.

I strapped my bag to the back platform and slipped in beside him. The door was barely shut before the car lurched into forward motion and we were off. I grabbed the two side scarves and tied them under my chin for the drive into the countryside south of Cambridge town.

“Will I ever get the smell of formaldehyde out of my hair?” I needed to shout to overcome the wind blown directly into our faces and the “infernal combustion engine,” as my father called the Packard. I put my wrist to my nose. “I think the stuff’s in my skin as well!”

“It is!” Father called out cheerily. “Formaldehyde is organic and seeps into the skin. You’ll smell like a cadaver for the rest of the term! Perhaps longer. Every year before the summer break all the anatomy students get together on King’s Court, set a huge bonfire, and burn their odious black coats!”

I liked the sound of that tradition and imagined the heat of the fire, the raucous shouts, and the glow of the flames on the faces of the Messrs. Woodley, Shaw, and even Cartwright. There was something wonderfully pagan about the ritual.

Everyone knew Professor Porter’s blue Packard and waved merrily to him as we tooled along Gwydir Street and the Brewery, then passed the Mill Road Cemetery and on out of the city limits. Cambridge was a smallish town. It wasn’t long before we were driving southwest on Whimpole Road through green farm and pasturelands.

“Well,” Father said, “what did you find in your specimen’s throat?”

“All the organs and structures necessary for the muscles of speech! The hyoid bone, the larynx, the tongue and pharynx. I took a good hard look at the supralaryngeal air passage. I’ve studied the voice box in theory and lecture, but it was amazing to finally see the very organ that makes our species human!”

“Don’t let’s forget upright posture in all the excitement. You’d have quite a fight on your hands with our fellow evolutionists if you showed them a knuckle-dragging ape, even if he could sing ‘The StarSpangled Banner’!”

I carefully considered my father’s words. He was right. Sometimes my enthusiasm got the better of me. I tended to forget the obvious.

“Remind me tomorrow,” he continued, “but I think I’ve got the larynx of a mountain gorilla in the pantry!”

Much to Mother’s dismay, Archie Porter called the specimen closet in his home laboratory the pantry. It truly was a grotesque chamber, worse in ways than the human dissection laboratory at the university. Before Father had become a lecturer of human anatomy, he had been a morphologist—a comparative anatomist—studying and dissecting a variety of animal species. He therefore kept, in row upon row in his pantry, body parts, embryos, specimens, and skeletons of every sort of wild and domesticated animal.

In this one instance, and possibly this one instance alone, I found myself in agreement with Mother. Even as a young girl I’d hated the sight of half a dog’s head in a jar, the rather large phallus of a stallion, a pig embryo, a skinned cat. And not because they were hideous or frightening. In fact, they’d fascinated me. But I adored animals (in their living condition) and felt nothing but pity for the poor creatures who had been so unceremoniously cut into pieces, ending up pickled in Father’s closet. It suddenly occurred to me that I’d had no such qualms that morning in the human anatomy laboratory. But then, I had more love for animals than I did most people I knew.

“While the human is fresh in your mind,” Father said, “you should have a look-see at the ape!”

“That would be brilliant!” I called out, grateful enough for the extraordinary opportunity just offered to overcome the revulsion I felt for the unfortunate simian.

Father was proud of his collection. Every summer for the past six years he had gone on expedition to Kenya, timed between that country’s two rainy seasons, in furtherance of his lifelong quest. He, like his friend and associate Eugène Dubois, had been searching for Charles Darwin’s missing link. Dubois, in 1891, had had the good fortune to find in the wilds of Indonesia the fossil remains of Java man, what my father believed was “stunning proof” of an interim species, part ape, part man. But this had, ironically, proved to be only the beginning of the poor man’s travails. The scientific establishment had, by and large, repudiated Dubois’s finding. Ever since his return to Europe with his precious bones, having nearly lost the case holding them in a shipwreck, the Limburgian paleoanthropologist had been compelled to defend his fossils against those “too dense or jealous,” as Father would say, to admit his accomplishment. And all this after years of intensive work and massive personal sacrifice— the appalling loss of an infant daughter to a tropical fever and a wife who had lost her love for the man with the death of their child.

Father’s only dispute with his friend was one of location. Eugène Dubois, on the urgings of his professor at Jena University—the esteemed Ernst Haeckel—had gone looking for the ape-human link in the jungles of Asia. Professor Porter, a more literal Darwinist, was certain the fossils would be found in equatorial Africa.

Dubois had returned home from Java carrying tangible evidence of an upright anthropoid with a large brain—far larger than any ape’s, though not quite as fulsome as the Neanderthal skulls discovered in Europe. Alas, it had no neck vertebrae or any evidence of the power of speech. But Father had so far found less than that. Nothing at all but fossils of extinct flora and fauna of the Pleistocene epoch. He had also harvested quite a collection of unwanted body parts as specimens from the carcasses of apes taken down by the numerous great white hunters now making a fine living in Kenya with their wealthy clientele, out for adventure and trophies for their library floors and walls.

Certainly he was frustrated, but each year without fail he mounted a new, insanely expensive expedition, financed by my mother’s vast fortune. The money was grudgingly given, as Samantha EdlingtonPorter loathed the months her husband disappeared into the “Dark Continent.” She was mortified by his theories and endeavors, which were similarly disavowed by his fellow scientists. While they might agree with Darwin’s theories in Descent of Man, few had any interest in finding physical proof of them. Well respected though Archie Porter might be in his professorship at Cambridge, he was merely an “enthusiastic amateur” in his paleoanthropological adventures. I always thought it to my mother’s credit that despite her dreaded misgivings and the whiff of scientific heresy that surrounded the hated safaris, she repeatedly funded them.

Father did, however, pay a price. There were the acid comments at Mother’s dinner parties and the incessant harping about the dangers of these expeditions. In one respect, at least, she did have firm ground upon which to level her assaults.

For beating in Archie Porter’s broad, manly chest was a questionable heart. It was a family thing, he liked to say, much like the Hapsburg lip. His father, two uncles, and a brother had died young from what Father referred to as “a bum ticker.” But he insisted—quite rightly, I thought—that his kin had been wholly unfit individuals, carrying before them massive bellies and jowls hanging heavily from their chins that shook like beef aspic on a platter. Father was an altogether different sort—a bona fide outdoorsman. He fished, he rode, he bicycled. He took miles-long striding constitutionals every single day that weather permitted. And I, the only one of his and Mother’s children who had survived infancy, had taken very much after my father.

Samantha cringed when anyone called her daughter a tomboy, but that was a perfectly reasonable description of me. Much as I loved reading and the study of science, I honestly preferred the out-of-doors. Never was I happier than on the back of a galloping horse, my yapping hounds running alongside. Not to brag, but I was a crack shot, too. I could outshoot Father at skeet, and my begrudging nickname on the college archery range was “Robin Hood.” Long ago, Mother had given up seeing me descend the staircase slowly and decorously, my hand pressed lightly on the rail. I had proved myself to be little more than a female ruffian.

“So were they horrible to you today, the young men in the class?” Father shouted over the wind.

“Only one true dolt!” I shouted back in answer to his question, thinking of Mr. Cartwright.

I noticed that Father’s wavy brown hair, blown backward, was growing rather longer than Mother liked, and it was always an unruly mess by the time we returned from the college. He had refused to grow the full beard that was all the rage now, especially among English academic men, choosing instead the clean-shaven American style. His wife approved of the beardless look but strenuously objected to the too-long hair. “You look like the Wild Man of Borneo,” she would complain every time he came in from a drive. And when it attained a dangerous length—as it had now—Samantha would have the barber make a special house call.

“But it makes me so angry, Cambridge segregating the men and the women!” I said. “Why haven’t they come into the new century? Look at Marie Stopes at University College London. Not only are females training side by side with male physicians, but Marie, a girl my age, is already a lecturer there!”

“You could have gone to University College!”

“I know I could. But then I would have had to leave you!” I looked over at my father, affection threatening to spill over as tears. “And your laboratory!”

“Our laboratory!” He smiled, never taking his eyes off the road. Archie Porter was nothing if not a careful man.

I was warmed to be reminded that he trusted me as his assistant in his private work at home. Depended on me more and more all the time. It was why I relished every weekend I could steal away from the university. To work at his side.

“If you test well in human dissection—you’re already top of the class in lecture—you just might open some doors for young ladies in the future!”

The Packard turned into the long manor drive and pulled up to our stately home—the Edlington-Porter manor house with its fine stonework and high arched windows. Now Father spoke in normal tones, filled with the warmth and familiar affection I so loved.

“Meanwhile, you’d best sneak upstairs and stick your head in a bucket of lemon juice before coming down to dinner. I’m afraid I’ll never hear the end of ‘our reeking daughter smelling of the dead.’ ”

The doorman came to my side and opened the Packard’s door. “Welcome back, Miss Jane.”

Then the hounds were there to greet me, setting up a fine racket, sniffing wildly at my new and enticing fragrance.

“Come on, boys,” I said, eager to get to the stables, “let’s go see if Leicester wants to have a ride”

Jane © Robin Maxwell 2012