November began with a trip to Utopiales, a huge French SF festival in Nantes, followed by a lightning trip to the UK to see King John at Stratford and Henry VI at the Globe in London, then back to Paris for some bookstore events and the Louvre. Then I came home to find winter had set in: 20cm of snow and -10C on the day I got back. I had the proofs of Or What You Will to do, but otherwise plenty of time to read and little desire to go out of the house. I read 22 books in November, and here they are.

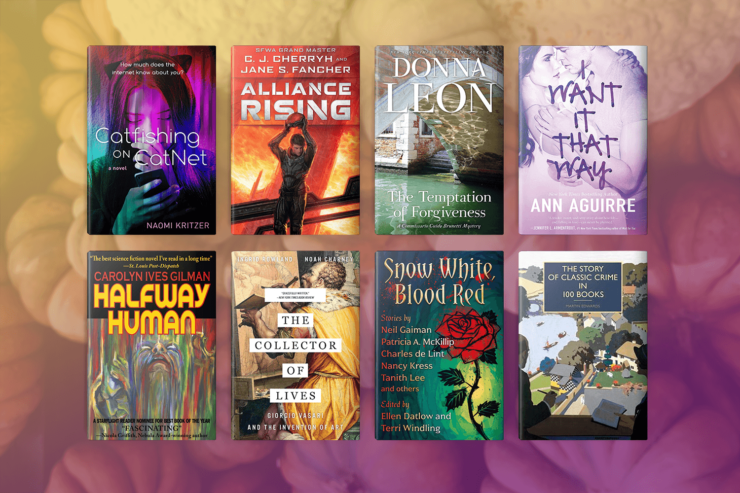

Halfway Human, Carolyn Ives Gilman, 1998.

This is an absorbing and fascinating anthropological SF novel that gives us two far future cultures like and unlike our own, with interesting angles on gender, families, society, and the way changes in transportation and contact with others transform cultures. If you like either A Million Open Doors or A Woman of the Iron People you should read this. If you like the POV in Murderbot you should definitely read this. I don’t know how I missed it in 1998. Glad to have found it now.

The Collector of Lives: Giorgio Vasari and the Invention of Art, Ingrid Rowland, 2017.

A book from which I learned many things, but not sufficiently interestingly written that I’d recommend it unless you really want information about Vasari’s life and times.

It Pays To Be Good, Noel Streatfeild, 1936.

Re-read. I read this when Greyladies republished it about ten years ago, and I re-read it as an ebook. It’s another book that reads like a weirdly inverted version of one of her children’s books. It’s the story of an utterly selfish immoral girl who succeeds from the cradle on because of her beauty and lack of scruples. Many of the minor characters are sympathetic and much more interesting. Contains the weird belief (minor spoiler), on which I was also brought up, that if you go swimming after eating you will have a heart attack and die.

Wife For Sale, Kathleen Thompson Norris, 1933.

Re-read, bath book. Norris writes books whose plots I can not predict, and yet on re-reading they seem logical and reasonable. This book employs a trope she often uses of poor people unable to get ahead in town thriving in the country—in this case New York and rural New Jersey—but is otherwise unlike most of her plots. A girl loses her job in 1933, and writes a letter to the paper looking for somebody to marry her. A man replies, and then the plot doesn’t do anything you’re likely expecting from that set up. Antarctic expedition, for instance.

The Fated Sky, Mary Robinette Kowal, 2018.

Sequel to this year’s Hugo winning The Calculating Stars. I can’t help but find The Fated Sky disappointing. I wanted to like it—it’s a book with its heart in the right place, and I’m entirely in sympathy with that, but somehow there wasn’t enough to it. It is, like its predecessor, a traditional old fashioned SF story about the nuts and bolts and politics of American space travel, in an alternate history where it’s all taking place a decade earlier and with women and PoC and even, in this book, a handwave in the general direction of there actually being other countries on the planet! There’s a trip to Mars…but maybe I was in the wrong mood for it. Somehow it kept feeling like a series of ticked boxes I was noting as they went by instead of a real story that could absorb me. Definitely had enough of this universe now.

The Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean: The Ancient World Economy and the Kingdoms of Africa, Arabia, and India, Raoul McLaughlin, 2014.

This book could pose by the word “meticulous” in the dictionary. McLaughlin has gone through every possible reference textual, archaeological, economic, Roman, Indian, everywhere else, and connected it all up and joined all the dots to bring us a book about Rome’s trade with the Indian Ocean in all its details. This is not a quick read or an easy read, but it’s certainly a thorough one.

A Ride on Horseback Through France to Florence Vol II, Augusta Macgregor Holmes, 1842.

I read Volume I earlier this year. If you want to know about the state of roads and inns in Italy in 1842 (terrible) and the history of the places you might pass through, along with the state of mind of the writer’s horse, Fanny, this is the book for you. I was deeply disappointed by what she said about Florence—she didn’t care for it much, after coming all that way! Free on Gutenburg.

The Best of Poetry: Thoughts That Breathe and Words That Burn, Rudolph Amsel and Teresa Keyne, 2014.

An excellent and wide ranging poetry collection. I love coming across old friends unexpectedly and discovering new things. Very interesting arrangement too. Also here’s a great poem for these times, Clough’s Say not the struggle nought availeth.

I Want It That Way, Ann Aguirre, 2014.

So, a YA erotic romance. I guess that’s a thing now?

Snow White, Blood Red, Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling, 1993.

Collection of re-told fairy tales, from the very beginning of modern fairytale retellings. Some excellent stories, especially by Jane Yolen and Lisa Goldstein, but some of them were a bit too dark for my taste.

A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf, 1929.

Re-read, ninety years on, and probably forty years since I first read it. I know a lot more history, and a lot more about women who did produce art despite everything, than when I first read it, and certainly women have produced a lot of amazing art since she wrote it, but I still find it a valuable feminist corrective, and itself beautifully written. I don’t care much for Woolf’s fiction—it seems to me dense in the wrong ways, and hard to enjoy—but this is very good.

The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books, Martin Edwards, 2017.

A discussion of the Golden Age of crime and some of its exemplars, set out by the expert Martin Edwards, who has edited so many of the excellent British Library Crime Classics. Mostly interesting if you are interested in classic crime and hoping to find some writers you have missed, or if you’re interested in what makes genres genres.

Letters From a Self-Made Merchant To His Son, George Horace Lorimer, 1902.

This fooled me on Gutenberg, I thought it was a real book of letters, but actually it’s a supposedly humorous self-help book from 1902 in epistolary shape. I mildly enjoyed it, but would not bother again. I’d much rather have a real book of letters, because this one very much is made up of the kind of things people make up.

Catfishing on Catnet, Naomi Kritzer, 2019.

This is wonderful, and while it is the first volume of a projected series, it has great volume completion, so you can happily grab this and read it now without waiting. If you liked Kritzer’s Hugo-winning short story “Cat Pictures Please” you will like this. This is a YA SF novel about a diverse and fun group of misfit teenagers and an AI who hang out in a chatroom, and how they deal with a real world problem. It’s set in the very near future, where there are just a few more self-driving cars and robots than now. It has well-drawn characters and the kind of story you can’t stop reading, as well as thought-provoking ideas. Just read it already.

On Historical Distance, Mark Salber Phillips, 2013.

This was also great and unputdownable, which you wouldn’t naturally expect in a book about historiography and trends in history writing from Machiavelli to the present, but it really was. Phillips writes in fascinating detail about how attitudes to history (its purpose, how we write it, and our relationship to it) changed in the Renaissance, again in the Enlightenment, and again after about 1968. Excellent book for anyone interested in history and history writing.

Smallbone Deceased, Michael Gilbert, 1950.

There’s a solicitor’s office in London, and a corpse, and a limited set of suspects, and red herrings, and—it’s all delightful.

Sex, Gender, and Sexuality in Renaissance Italy, Jacqueline Murray, 2019.

A collection of essays about what it says on the label. The one by Guido Ruggiero is the best, but they are almost all very interesting.

All Systems Red, Martha Wells, 2017.

Read for book club. Everyone in book club loved it because they are all introverts and identified with the first person character, but I found it a little thin on worldbuilding and depth. Also, I am not an introvert.

A Thousand Sisters: The Heroic Airwomen of the Soviet Union in WWII, Elizabeth E. Wein, 2019.

A non-fiction YA book. There’s an odd thing about knowing who your audience is. When I’m reading about something I know nothing about, I like non-fiction that assumes I know nothing but I’m not an idiot. This book didn’t assume that, but it seemed to be assuming I was about nine, and wanted lots of short sentences and exclamation marks. I didn’t when I was nine, and I found it a little odd now. Wein’s fiction is brilliantly written and pitched just right (especially Code Name Verity, which is such a wonderful book), so I didn’t expect this book to be clunky in this way at all.

The Temptation of Forgiveness, Donna Leon, 2018.

Another Brunetti book, a mystery which meditates on what it is to do wrong in addition to what has been done and who did it. These books are great. Not only do they contain Venice, and all the satisfactions of a crime story where there is a mystery and a solution uncurling themselves neatly, and continuing very real characters, but they also have this moral dimension that most such novels go out of their way to avoid.

Alliance Rising, C.J. Cherryh and Jane S. Fancher, 2019.

Re-read. I read this in January when it was released, and I re-read it now because it’s great. It’s set before Downbelow Station and indeed, is the earliest set book in the Alliance-Union chronology, and I spent a lot of mental effort trying to make it consistent with Hellburner and can’t, quite. Nevertheless, a great book, with a space station, ships, the economic and political upheavals that come with the invention of faster-than-light travel, a romance, a young man out of his depth (it is Cherryh after all) and intrigue. Not perfect—I was a little disconcerted by how comparatively few women there were for a Cherryh book, and wondered if this was Fancher’s influence. But an excellent book that stands alone well, definitely one of the best books of 2019.

Thus Was Adonis Murdered, Sarah Caudwell, 1981.

Re-read, bath book. This book is interesting mostly for its unusual narrative structure. We’re told at the beginning that Julia is accused of a murder in Venice, and that Hilary Tamar our (first person, slightly unreliable, but very funny) narrator discovers the truth and exonerates her. We then read letters and discussion of letters, in which we learn all kinds of events in Venice out of order, while Hilary remains narrating from London, so everything is distanced and reported. We get to meet suspects through Julia’s epistolary POV and through Hilary’s direct POV, but details such as the identity of the victim and the nature of Julia’s evolving relationship with him are trickled out. The way we are given information throughout the book is fascinating and unusual. The other noteworthy thing is gender—not the triviality that Hilary’s gender remains unstated, but that this takes place in a universe in which women are sexual predators and beautiful young men sexual prey, for both women and older men, and this is axiomatic. This was in fact not the case in 1981, and is not now, but nobody within the novel questions it.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two collections of Tor.com pieces, three poetry collections, a short story collection and thirteen novels, including the Hugo- and Nebula-winning Among Others. Her fourteenth novel, Lent, was published by Tor on May 28th 2019. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here irregularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal. She plans to live to be 99 and write a book every year.