Jodorowsky’s Dune is a documentary about Very Important Men making Very Important Art, and as such, it has very little to do with Frank Herbert’s novel at all. In fact, you could go so far as to say that it has nothing to do with Dune, either philosophically or artistically.

And that’s for the best, really.

[Content warning: discussions of rape]

The art of the documentary is all about framing, and director Frank Pavich certainly had some dream material cut out for him with this glimpse into what many film critics cite among the “greatest films never made.” Alejandro Jodorowsky is the perfect interview subject, full of excitement and anecdotes, host to a sort of prophetic mania. He describes most events in his life as though they were destined to happen by divine spiritual intervention. Indeed, he starts by explaining that the point of making Dune was to create a film that was both religious experience and an LSD trip printed onto celluloid—in fact, he seems to believe that those desires are essentially one and the same thing.

The story begins by highlighting Jodorowsky’s path up until the Dune project. It talks briefly of his career in theatre and then his move to films, covering Fando y Lis, El Topo (propped up here as “the original midnight movie” by Hardware director Richard Stanley), and The Holy Mountain. Jodorowsky goes on at length about how he broke all the rules to make his pictures, writing and starring in his own material, refusing to run Lis by the Mexican director’s guild for permission to make it; Fando y Lis later caused a riot due to its graphic content and was banned from the country entirely. He explains that he knew nothing of filmmaking’s technical aspects, learning everything as he went for the sake of art, that lofty goal of the spiritually enlightened. Those who are not familiar with Jodorowsky’s milieu are treated to a selection of imagery that gives the viewer a sense of what they’re in for—it’s all surrealism with a distinct erotic bent, mostly-naked figures and women sporting whips and repurposed religious iconography set against stark color-contrasted backdrops. It’s the sort of shocking fare that the 1960s and 70s produced in abundance provided that you were in the right arthouse circles.

No women are available to talk about Jodorowsky’s work—no film producers nor directors nor critics. The only two women interviewed in the entire documentary are there to talk about other men involved in the project who have passed on and cannot speak for themselves: special effects guru Dan O’Bannon’s widow, Diane, and Amanda Lear, who was Salvador Dali’s muse at the time that Jodorowsky approached him about the film. (Apparently, he was going to give Lear the part of Princess Irulan, though she doesn’t look at all convinced in retrospect.) Everyone else involved in the documentary is a man, from producers Jean-Paul Gibon and Michel Seydoux and Gary Kurtz, to directors Richard Stanley and Nicholas Winding Refn, to film critics Drew McWeeny and Devin Faraci. All of the artists on Jodorowsky’s Dune team are men. This cannot be viewed as incidental; there is an implicit suggestion that only men are capable of being Jodorowsky’s “warriors” (his word, by the way, to describe those he would ask to come on his quest), and as is true of any number of religious pantheons full of prophets and apostles, the perspectives of women are rarely entertained as gospel.

The documentary proceeds to follow a trail of breadcrumbs as Jodorowsky assembles his team of warriors for the project. All of this is framed as though some greater power is manipulating fate to give him the perfect players for his magnum opus; he happens across Salvador Dali and hands him a tarot card of The Hanged Man to interest him in playing the Emperor; after deciding that he requires Moebius (that’s the SF moniker for French artist Jean Giraud) to create the world of Dune, they just bump into one another when Jodorowsky is visiting his publicity agent; Orson Welles agrees to be the Baron Harkonnen after Jodorowsky offers to get the chef of his favorite restaurant to cook for him every day; he wants Mick Jagger for Feyd-Rautha and stumbles across the man at a fancy party in Paris; Pink Floyd is too busy eating lunch during their break from a studio session, but Jodorowsky yells at them about how important his movie is going to be until they drop their burgers and agree to write music for him. Great man, great purpose, great art—an unstoppable force to be reckoned with.

Illustrator Chris Foss, who served as a concept artist for the film, admits that Jodorowsky excelled at motivating the team and getting them invested in the gargantuan process. Moebius, an artistic legend in his own right, agreed to storyboard the entire film, shot for shot, and H.R. Giger and Foss were asked to craft different aspects of the universe, with Foss focusing on the spaceships and architecture and Giger there to conceptualize Harkonnen grotesqueness. The idea of using different artists for different pieces of the film is certainly a clever one, and would have given each aspect of the tale a distinct flavor that could be easily distinguished from one another. We hear repeatedly about how far Jodorowsky was willing to go for the sake of this movie—including offering his own son up to play the role of Paul Atreides. Twelve-year-old Brontis Jodorowsky proceeded to train in a multitude of fighting techniques six hours a day, every day, for two whole years. No one treats this as inhumane or unreasonable: it is the selfless pursuit of reality as an artistic discipline. You can’t play Paul Atreides without becoming him. The film was set to be anywhere up to fourteen hours long—anything to make certain that its artistic integrity was preserved, that no limits were placed on anyone’s imagination.

Despite all of this, as we know, the plans fell apart and the movie never saw the light of day. A massive tome of art, storyboards, and intricate plans were assembled to convince Hollywood execs to pony up fifteen million dollars—an extremely hefty sum in 1974—for Dune to come to fruition. While everyone was impressed with the scope and vision that went into this biblical guide for the production, no major studio was prepared to take a risk on Jodorowsky himself. In the documentary, it is painted as the might of corporatism stomping its great gilded boot all over an artist’s dream, his uncompromising vision. It is even suggested that if this version of Dune had been made, the face of blockbuster cinema would have been forever altered, wiping away our current landscape of superhero carbon copies and Star Wars merchandising. The world would be better and brighter if Jodorowsky’s Dune had only been allowed to escape its genie’s bottle.

The documentary weaves a spell around Jodowosky’s work, building the man into the sort of legend who could create the great religious film experience of all time. The end of the story is chock full of examples showcasing popular films that seem to have cribbed from the big conceptual book that they passed along to studio executives—places where Contact and Star Wars and Flash Gordon and Raiders of the Lost Ark may have wittingly or unwittingly lifted from their work. If you buy that conceit, there’s a sense of theft, of lesser beings diluting the message of a greater work, that reads as truly painful… but what of the work that Jodorowsky himself was stealing from? What of Frank Herbert’s Dune, a book that he barely seems to have considered in the making? Every time he brings up the novel, he only seems to talk of what he intended to change about it.

To that end, the finale of Dune was meant to show us the death of Paul Atreides—but he is resurrected in the consciousness of everyone who knew him. Everyone becomes Paul, and the world of Arrakis morphs into a garden planet of life that hurls itself throughout the cosmos to spread enlightenment. Which, very much like David Lynch’s interpretation, is the exact opposite of the message that Frank Herbert intended to impart. But Jodorowsky isn’t bothered, because according to him, he had no obligation to consider Herbert’s text in the pursuit of his own artistic vision. Here is what he says toward the end of the documentary:

“It’s different. It was my Dune. When you make a picture, you must not respect the novel. It’s like you get married, no? You go with the wife, white, the woman is white. You take the woman, if you respect the woman, you will never have child. You need to open the costume and to… to rape the bride. And then you will have your picture. I was raping Frank Herbert, raping, like this! But with love, with love.”

…And just like that, it all falls to pieces.

Just in case anyone ever remotely considering defending this word choice, calling it old-fashioned or a metaphor (and even if that were the case, it would be a terrible metaphor), permit me to direct you to Son of the 100 Best Movies You’ve Never Seen by Richard Crouse, which contains a sample from an interview Jodorowsky gave about Fando y Lis in 1970, where he admits that he actually insisted on being beaten by his costar and then raping her for the purpose of the film:

“After she had hit me long enough and hard enough to tire her, I said, ‘Now it’s my turn. Roll the cameras.’ And I really… I really… I really raped her. And she screamed. Then she told me that she had been raped before. You see, for me the character is frigid until El Topo rapes her. And she has an orgasm. That’s why I show a stone phallus in that scene… which spouts water. She has an orgasm. She accepts male sex. And that’s what happened to Mara in reality. She really had that problem. Fantastic scene. A very, very strong scene.”

It’s not a metaphor. We are dealing with an artist who condones rape as a means to an end for the purpose of creating art. A man who seems to believe that rape is something that women “need” if they can’t accept male sexual power on their own. Suddenly, ignoring Frank Herbert’s intended theme about the misguided deification of mortal men seems like the most mild thing Alejandro Jodorowsky could possibly do—though it does appear to be a theme that he could sorely use a primer on.

But, more to the point… is it really possible to come up with a better showcase for male privilege in the artistic world than this very film? Jodorowsky lectures on about how “the system” is nothing but money with no soul, with no integrity, and that movies contain truth and the stuff of dreams. He rails against the evils of rich Hollywood suits who couldn’t understand the beauty of what he planned to show them because he believes that he deserved their instant support. And when he didn’t get it, the world still conspired to make a documentary about his beautiful failure, because genius should be admired even when that genius belongs to a rapist who thought that sexual violence needed to be explored for art’s sake, by a man who was enacting that violence upon someone else in order to communicate his “truth” to the world. He’s responsible for the original midnight movie; you had better show him your unflinching respect. He makes real art, and real art is glorious and unknowable but also ugly and obscene, and too bad about that. Art doesn’t require trust or respect or basic human decency because genius tells us so.

Oh, look—I think I figured out why no women wanted to be interviewed about Jodorowsky and his plans for Dune. Or why they were never given the chance in the first place. I guess we can leave that to guys like Devin Faraci, and to directors who are excited to be christened Jodorowsky’s “spiritual son” after being expelled for throwing tables into walls back in art school. How illuminating.

It’s no great tragedy that Jodorowsky’s Dune never got made. Everyone involved went on with their highly successful careers anyhow, and we arguably got a better film out of it—because Dan O’Bannon, Moebius, Chris Foss, and H.R. Giger all went on to create Alien. But if there’s one thing the world definitely doesn’t need, it’s more praise for the murky genius of men who compare Frank Herbert’s writing to Proust. (Jodorowsky did this. I can’t think of a writer who Herbert is less comparable to than Proust, except maybe Sylvia Plath or D. H. Lawrence.) Art doesn’t have to be a Sisyphean feat in order to mean something, and while it’s always intriguing to mull over what might have been, a better version of our timeline is not automatically waiting at the other end.

In this case, it’s just as well that we have some gorgeous artwork to mull over… and little else.

Emmet Asher-Perrin would accept a coffee table book of the artwork, but sort of wishes she hadn’t seen this documentary at all. You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.

Fair. Jodorowski really did roll a natural 20 on charisma – he talks in such a spellbinding fashion that you listen in awe until your brain quietly taps you on the shoulder and goes “hang on just one minute he said WHAT?!”

If you like the artwork, I can recommend the most recent Chris Foss book – I got it a few years ago at Worldcon. Moebius I haven’t seen any good books of yet – most are honestly very poor reproductions. HR Giger gives me the creeps.

The more I hear about this guy and his “vision”, the more I’m glad this movie never got made. As much as I loathe the Lynch Dune movie, this sounds much worse.

This is truly a bizarre look into what seems to be quite a charismatic megalomaniac. It might just be my own limited perspective, but it seems like this is very 70s. Then again, I suppose even recent history is littered with these types even if they don’t frame it in such ‘artistic’ terms. How bizarre. I already reacted to the ‘rape’ as therapy idea in the previous thread so I will just leave that alone.

If he was going to ignore the source material why not just write his own screenplay without Herbert’s names?

For the same reason Kubrick didn’t re-title his monstrous revision of The Shining by another title… He didn’t want to adapt someone else’s story, he wanted to masturbate his ego with another artist’s work.

Oh. Yeah that explains it.

I understand the reasoning behind the article, but it feels like recently on the internet there seems to be a trend of going back and looking at media and projects from 30 or 40 years ago, and then judging them via modern standards (along with an air smug self righteousness about how much more evolved we are currently). It just seems counter productive to me, I not saying we shouldn’t look back at things and realize how far we’ve come (and far we have to go) . It just seems there’s a weird sense of superiority involved in this -“In this case, it’s just as well that we have some gorgeous artwork to mull over… and little else.” Is it really? The Seventies was an era of a lot of radical experimentation in film and art, and maybe Jodorowski has the wrong end of the stick when it comes to his interpretation, but I don’t think its anyone’s place to say we’d better off with out it .

@7 It sounds pretty bad even for the seventies. Even judging it by the standards of the time may not prove favourable to it. Not to mention, even leaving aside the really awful bits, it sounds like the recipe for a terrible movie.

In the same way that H.P. Lovecraft was notably awful compared to most of his contemporaries. They might have all been racist, but he was *really* racist.

@7: The Seventies were a time of radical exploration in film, and art, and music, and politics. They were also a time when a lot of women took a look at just who was getting to do the experimenting, and at some of the very old ideas under all the new looks, and basically said “What the hell?” There was plenty of judging going on at the time.

Whatever the faults of so-called second wave feminism as judged forty years later, it didn’t arise unprompted out of nowhere.

@@@@@ I’m taking the piece as a response to the 2013 documentary on the film as well as to the film itself. It sounds as if the documentary took Jodorowsky at his own value, boosting his myth. (I’ve not seen it, but its director seems to be quite the fanboy). If it’s okay for a one person to adulate a past project and its creator, it’s surely okay for someone else to push back and dissent.

And enough already with the “Don’t judge by modern standards” line. Learn from history, or end up repeating it: choose one.

Jesus, I had no idea Jodorowsky was such a remarkable shitheel.

The only part of this movie I wish had been made is the dueling Pink Floyd/Magma soundtrack, because that sounds fucking awesome.

I saw this documentary when it was at the Toronto Film Festival a few years ago (mostly because my friend got free tickets). It was such a weird experience to watch people talk about how amazing this movie would have been, if only it was allowed to be made, but then listen to them explain how bat-feces insane and nonsensical it actually would have been. I mean why would anyone think that a 14-hour LSD trip would be an enjoyable film? It was just so incongruous.

My only exposure to Jodorowsky has been through this film, and I have had no interest in learning more about him. This article is just solidifying this for me even more.

Jodorowsky’s “psycho-sexual-magic” public advice in twitter is equally WTF-inducing…

This is from last year:

“(Q) When I was a little girl I was sexually abused. Now, even though I love him, it’s hard for me to sexually desire my husband // (A) Make him disguise as your rapist, and you will be sexually aroused…”

As you may expect, there was a big, negative response for him in the spanish-speaking corner of twitter…

I think a bigger problem with making any Dune movie than the individual foibles (to put it mildly) of any one director is the fact that the series is fundamentally obsolete in the same way that John Carter is/was.

But heaven forbid we judge this guy on modern standards ;)

@13, with every new bit of information I learn about the guy, he seems even more of an… unsavoury individual.

@14, fundamentally obsolete? Care to explain that?

I understand the reasoning behind the article, but it feels like recently on the internet there seems to be a trend of going back and looking at media and projects from 30 or 40 years ago, and then judging them via modern standards (along with an air smug self righteousness about how much more evolved we are currently). It just seems counter productive to me, I not saying we shouldn’t look back at things and realize how far we’ve come (and far we have to go) . It just seems there’s a weird sense of superiority involved in this -“In this case, it’s just as well that we have some gorgeous artwork to mull over… and little else.” Is it really? The Seventies was an era of a lot of radical experimentation in film and art, and maybe Jodorowski has the wrong end of the stick when it comes to his interpretation, but I don’t think its anyone’s place to say we’d better off with out it .

Indeed, all of the above applies.

It’s irresponsible to condemn an author like this. You have to set the person and his/her work apart. One has to distance the author from the material itself, otherwise no one will be watching much of anything. By this limited mindset in frank display on this thread, should I avoid watching anything made by a filmmaking genius like Polanski, or a well written character piece like many of Woody Allen’s? Next thing you know, you’re boycotting films from certain filmmakers because you disagree with their politics.

Honestly, I call BS on this whole “moral outrage” going on on the piece itself and several of the comments.

Who knows what might have happened had his version of Dune actually been released? I probably would have enjoyed it. It was the 1970’s, a period rich in experimentation.

@17 Only if Polanski or Allen’s work promote or depend on the crimes or attitudes for which they are condemned. Since Jodorowsky’s attitudes seem fairly well integrated with his planned project, I think it’s fair to consider both art and artist in this case.

Likewise, I’ll still read some of Orsan Scott Card’s older work but not his more recent efforts which have been infiltrated by his more odious political beliefs.

@17 – You can’t separate a criminal from the crimes they commit.

The so-called artist in question committed the crime of rape. He admits this. The fact that he filmed it and wanted it for a movie doesn’t make him less of a rapist.

If he had murdered an actor on set, for the sake of an artistically accurate murder, would anyone be making excuses for him? Would the fact that it was the 1970s somehow make that murder okay?

Why should the crime of rape be the one act of violence that gets excused as “art”?

When art becomes an excuse for violent crime, it ceases to be something that can be considered only as art.

When I was in college, I had a (male) women’s studies professor who insisted that Jodorowsky was an “unsung genius” and who openly lamented that Jodorowsky’s vision of Dune never came to fruition. I still can’t wrap my head around that.

After watching this documentary last year, one feeling I had was quite strong: that Jodorowsky had never actually read Frank Herbert’s novel. He may have skimmed it, had others summarize it, and had artists depict characters and scenes from it, but I don’t think Jodorowsky himself sat down and read the novel cover to cover.

Jodorowsky raped his costar, Mara Lorenzio, in El Topo not Fando y Lis.

@@.-@: While I’m glad that Jodorowsky didn’t get to do his thing and call it Dune, I think the best answer to “Why didn’t he just write a screenplay called something else?” is “Because there would’ve been no chance of getting anyone to produce it.” Framing his project as an adaptation of something very famous (especially something with a reputation for being weird and trippy, so that a famously weird and trippy director might seem superficially appropriate for it) was probably the only way Jodorowsky could’ve ever hoped to get anywhere near a Hollywood budget. He eventually figured out that if he wanted to turn big intricate SF/fantasy ideas into visual form, his best bet was to write comic books.

Excellent piece–thanks for so wonderfully articulating my issues with Jodorowsky as both a person and an artist, his bizarre take on Dune, and this doc in particular. I’m not quite sure why anyone thinks he’s a genius… or why they’re so willing to look past all the indicators that he’s an egotistical, wretched person.

When I first saw this I was excited, you know, a new documentary about an realized version of Dune? Sure! And that was it, it was clear he never read Dune, nothing about his vision for Dune is even remotely close to Dune. I mean say what you will about David Lynch’s Dune at least its framework was still Dune, Jodorowsky’s Dune was just terrible, I don’t care if its art, if its genius that no one can ever see, and I don’t care of Giger and O’Bannon were involved. The guy is nuts, his dream of Dune is extremely off base, and I”m rambling, sorry. After it was over I was less wowed and more like ‘well, that was something I saw.’ I mean, 15 hour LSD trip? I don’t even know art house snobs who’d sit through 15 hours of whoever discovering their ego and their messianic rape sex life fulfillment of spiritual enlightenment. No, Jodorowsky’s Dune should never be allowed to see the light of day.

My favorite onscreen Dune is still the SciFi channel Dune

I admit that when I saw the documentary last year, I did find it kind of fascinating. But that was before I knew anything about Jodorowsky’s more unpleasant proclivities. I don’t think I’ll be settling in for a repeat viewing.

Do love the Chris Foss art, though. Plus Moebius and Giger and some of the other folks who went on to do bigger, better, and less insane things.

Believe or dont believe but this article is a poor attempt to cover up the real reason why the film was never made. Simply they stole the imaginary and the ideas of Jorodowski and made something else. They pocketed the cash and never even recognised tge real authors copy rights. Typical intellectual theft by Hollywood n the US circus.

I could almost buy the line about ‘raping’ the source material or the inspiration for a particular project as a description of someone’s artistic process. It’s sorta accurate in a deliberately over the top way.

Of course the key here is to keep it on the level of metaphor, which this scumbag apparently doesn’t.

I’m so glad this movie wasn’t made. I found the documentary fascinating and horrifying at the same time. If there is one thing I cannot stand is tbat art instalation movement and thid Dune was gonna be just thar “Art”. And worst of all “art” straight out of the swinging 60s lsd drug culture. Nothing to do with the book and if this would come out it would destroy scifi at the movies for a very long time. This Dune would be a massive flop, the scifi panorama in the mind of the audiences would continue to be associated with lsd trips , and I can bet not even a space opera like stars wars would get a chance to come out on the backlash this dune version would get if it came out before.

This Dune project makes me cringe. And I actually loved lynchs version and really enjoyed the recent mini series. But dune as a lsd trip full of “art” ? Please no.

I agree with mr Gerald Walker at the comment no.7. I’ve enjoyed the documentary very much. I don’t like Jodorovsky but I respect his commitment to originality and purity of artistic vision. I don’t mind his rape comment because I never took it literally.

The author seems to be advocating moral lynch for those who exhibit a currently out of vogue thought-crime. That’s not helpful if we are all different and can enjoy different art.

I don’t like feminist stuff so I avoid it. You don’t like macho stuff? Avoid it. But let everyone create and enjoy the art that they like. A Holy Inquisition in the name of anything – God, communism, feminism, gay rights etc. – is just the same injustice.

I’m impressed with the actors and musicians he was proposing (Salvador Dali as emperor … that’s the coolest), but it doesn’t sound like he had anybody under contract. Imagining his Dune had gone forward, this still splits into multiple universes where some participants he supposedly lined up did and did not finally get involved. Mick Jagger probably has no recollection of meeting the guy, either now or even the day after he did.

If we can’t judge the past using values of the present, you’ve thrown away the yardstick for measuring whether society is any better off today for its various members.

@30, 32 – Except that he specifically isn’t just using rape as a metaphor. This person said that, in a previous project, he actually told the cameras to roll and than raped another actor.

That’s not a metaphor. That’s an admission of guilt, against one’s own interests.

Just what does someone have to do, to be considered guilty of rape, if admitting to the crime and filming it for the record isn’t enough?

Jodoworsky may be a genius. Certainly, his work in comics is considered by many to be so (The Incal,Metabarons – full of same shit, btw, is his Dune without Dune).

It doesnt make one bit of impact in the fact that he is, very much, the worst idiocies of the 60s and 70s supposed sex revolution and drugs and shamanic whatever the hell made person. As shown above, the whole absurdity of asking him for advice about what to do when your sex life like after rape (if he is not making the question himself, wouldnt put it past him) is only topped by his actual answer. You cant get a more idiotic, toxic, harmful point of view and again, he has learnt nothing – still goes dispensing bullshit New Agey “wisdom” and expecting the adoration of acolytes for saying “transgresssive” stuff like that.

Best I can say about him is that you can learn a lot from him as long as you limit it to craft of visual media and discard the whole supposed spiritual/psychological “enlightment” as the hackneyed sexist bullshit it is.

Even as a metaphor, the rape comments are unjustifiable, as well as being terrible as metaphor.

“If you want a child, you have to rape the bride”? Well, no, actually, you don’t. But that’s a pretty horrific view of sexual and reproductive relationships, if you take it literally.

And it doesn’t work well as metaphor either; Jodorowsky may be claiming to “rape Frank Herbert,” but what he’s shall we say interacting with is Frank Herbert’s novel. And it’s not possible to rape a text the way you can rape a person. All it does is imply that there can be such a thing as a good rape.

Furthermore, if you want to look at this attempted artistic creation as a “child,” seems to me Jodorowsky’s got his roles mixed up. Surely it’s Herbert’s novel that provided the “seed,” and only a seed, of an idea. And after Herbert’s spark of an idea was combined with Jodorowsky’s spark of an idea, it would have been Jodorowsky and not Herbert (let alone Herbert’s text) who spent his time building the thing into an actual full-blown production. That is, Jodorowsky would have been in the conventional maternal role– but you didn’t hear him claiming that Frank Herbert had raped him, did you?

@17: “It’s irresponsible to condemn an author like this. You have to set the person and his/her work apart. One has to distance the author from the material itself, otherwise no one will be watching much of anything.”

No. You may CHOOSE to set the work apart from the artist. I do, too, sometimes. Sometimes not. Sometimes I go halfway, where I refuse to directly provide financially support but might watch and enjoy the work received through other means. And sometimes I provide support knowing that a lot of not-awful people worked on it as well and they deserve compensation even if one of them doesn’t. It all depends on the circumstances, the amount of odiousness and how directly it bears on the work itself. It’s a moral balancing act everyone has to make for themselves.

You can’t force it on them any more than someone should force it on you to not watch it. They have a right to not watch a movie or read a book for any damn reason they want, they don’t owe the author, or you, anything. Sometimes I refuse to read a book because it’s got giant robots in it, and I just don’t like that. Sometimes people might refuse to read something, or dislike it if they do, for moral reasons, sometimes for strategic reasons that flow from it (for example, stories by bigots may have that bigotry manifest in the storyline in various and sundry ways, and, you know, there’s only so much time to read from so many books in the world, I don’t want to waste my time on ones that, judging by the author’s mindset, are more likely to have women only be sexual objects, for example).

And moreover, it’s far from irresponsible to condemn, because that helps other people make up their minds, weigh the issues and choose whether or not to support somebody who may in some instances have committed actual horrific crimes (in another Dune thread somebody said Jodorowsky’s “in-film rape” was discussed and agreed to with the actress beforehand and so the word “rape” was used in more of a metaphorical, role-play sense, and I honestly don’t know if that’s true… either’s disturbing in my book, because of the bizarre reasoning that went into the scene in the first place, but one’s significantly worse, and I’d never have known about either problem if somebody hadn’t condemned the author and I’d be pretty pissed at you if you prevented them from doing so and I went on to plunk down my money and later discovered what I’d just supported).

I read through the whole article, and skimmed it again a couple times while writing this, and, you know, I didn’t spot any moment where the author said anything like “you shouldn’t watch this movie because the director’s bad.” They gave their opinion based a wide variety of reasonings (including some involving the author’s moral character) that the hypothetical Dune movie would have probably been worse than not getting it, but they don’t say you can’t disagree, or you’re evil for wanting it, or that you can’t separate the art from the artist if you choose. You on the other hand said we HAVE to interact with art and artists in YOUR way, that it was irresponsible to condemn an artist for any beliefs they expressed. Perhaps you’re just being hyperbolic, but… you seem to be the one calling for restricting free speech here in ostensible defense of it.

This article was really thought-provoking. I haven’t actually seen the documentary, but I’m glad to have assumptions checked in advance.

Every professional wrestling fan who was watching 15 years ago knows the name Chris Benoit. A tremendously talented and nearly universally beloved talent who shocked the world when news broke that he murdered his wife and young son before committing suicide. WWE has scrubbed him from their history, and fans are torn on how to regard him; can you enjoy his old matches while condemning his final actions? Can you separate the two? There may never be a clear answer, but by all accounts he was a decent man before that fateful night. It is speculated that he did what he did because of brain damage due to a history of concussions. It wasn’t a “I believe these things all the time” thing, which makes it so very murky. It seems that fans of Jodorowsky see him the same way, but there really is no parallel, unless he has some brain damage from bad 60’s drugs that makes him think all sex is really rape. Which is just, I’m sorry, no. Jodorowsky isn’t a man who had a great career who then did one bad thing, he seems to have had a screwed up career from start to finish. This item is defective, send it back to factory.

@38: I don’t know whether Jodorowsky really thought that all sex is really rape.

But it occurs to me that, when Andrea Dworkin wrote that heterosexual intercourse in a male-dominated society had elements of coercion or degradation for many women, the outcry was “Feminists say that sex is rape! Bunch of crazy man-haters!”

When Jodorowsky made comments that imply that he doesn’t see much of a difference between sex and rape, the outcry was “What a creative genius!”

Wonder why that was.

(Meanwhile, I wish I had never read any accounts of Pablo Neruda’s life. A great career, and at least one bad thing.)

In this case, we don’t need to have decide between the art of the artist. Both seem to be terrible.

@39 Does Neruda’s one bad thing taint his entire body of work for you? Are you able to reconcile it? I’m not familiar with him, so I have no basis there.

The issue so many have with Benoit was the one bad thing was at the very end, and it was so very bad. There are so many famous people who have wildness in their early lives only to get clean and make good later, so it’s easier to overlook. So many rock bands flamed out after getting big and falling into drugs, but Aerosmith did their (arguably) best work after getting clean in the 90’s. Jodorowsky doesn’t seem to have one bad thing to reconcile, or a bad period that he got clean from, he seems to have always been a remarkable d-bag. To reconcile that would take a massive leap or a blind spot the size of Jupiter.

If anyone deserves a rip-snorting left-wing intersectional tell-me-off-athon it’s probably Jodorowsky. It does seem a little bit harsh though given that Frank Herbert had more than a few issues with his view of women…

Overall the piece convinced me that Jodorowsky would have been a much better fit for ‘God Emperor of Dune’, where his nightmare surrealism would have gone quite well with a story where the main character is a giant human/worm hybrid who has taken over the universe with his army of lesbians and is obsessed with expanding humanity’s consciousness through his weird breeding program.

What a well written article, I really enjoyed the style and content. Can’t wait for next weeks update

Ugh, thanks for this article, I will never waste time on watching this documentary.

Looking forward to starting the re-read on the next books which I never managed to get through. I have read the synopsis and find the general storyline quite intriguing, but I found the second book a terrible slog compared to the first.

I watched the documentary a few months ago on Netflix.

I had the same feeling about Jodorowsky’s intended project as I did about my middle-school friends’ idea to start a small appliance repair service; we had neither the training, the tools, nor the resources to do such a thing in any viable way. And neither did Jodoroswky.

Wow. I saw this a couple of years ago, and found the old man quite charismatic and interesting. But, I was a good deal more sympathetic to Jodorowsky referring to raping a text than raping a person. Problematic word choice? Sure. But my attitude toward adaptation in general is that the original work may or may not be germane to the adaptation, because the original work will still exist regardless of what gets cribbed from it. Remakes and adaptations aren’t a threat to the original work (in my opinion), and may even direct new people to discover it who would not have done so otherwise.

“Rape” is a common and dismissive piece of language used (by men and boys) to describe this act (a quick google search for “George Lucas raping my childhood” will confirm this). That doesn’t make the language use right, but we’re still talking about a dismissive attitude about adaptation that I generally approve of, even if I don’t necessarily approve of all the words used to describe it.

Conversely, “I raped my co-star to create art” is just unconscionable.

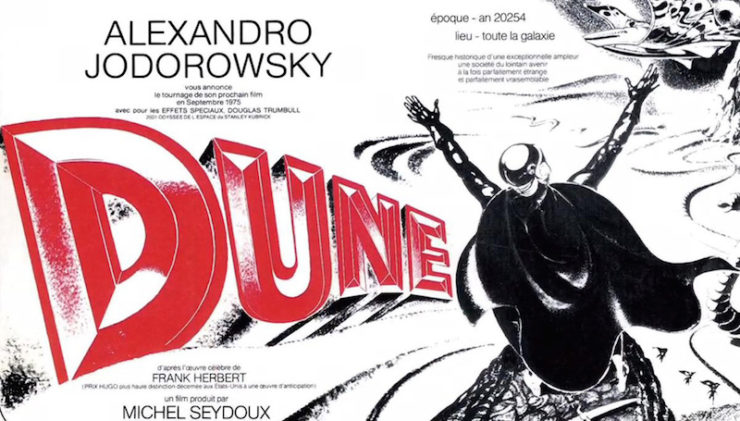

When I saw that poster in the middle of the article with the red “Dune” title, I couldn’t help thinking, “Why is Darth Vader on Arrakis?”

As for his sexual comments, I don’t think there is any defense for them. He has his head in the wrong place on the issue of rape and he has very little empathy for women who have gone through it. For such a supposedly great artist, his horizons are quite limited, as a person.

Given the lack of women among his warriors, who is the woman in the middle of the first photo of this article?

Another thing concerning El Topo : Brontis Jodorowski played the son of the “hero”. Wikipedia resume the opening of part one as : “The first half opens with El Topo (played by Jodorowsky himself) traveling through a desert on horseback with his naked young son, Hijo. They come across a town whose inhabitants have been slaughtered, and El Topo hunts down and kills the perpetrators and their leader, a fat balding Colonel. El Topo abandons his son to the monks of the settlement’s mission and rides off with a woman whom the Colonel had kept as a slave.”.

And note that Brontis was born in 1962, and the movie filmed in 1969.

No other comment.

All this documentary did was cement the idea that this would have been an awful Dune film, and that Jodorowsky is a disgusting maniac. What he did to his son is despicable, I wonder what kind of life that poor kid might have had. And let’s not get started in all of his “rape” speeches, that his supporters will defend saying “it’s symbolic, it’s an act of psychomagic”. Jodorowsky is, at best, a quack, and at worst, a dangerous sociopath.

I never stopped to consider that there were no women talking about the film, except for those two widows you mention. Good point.

And all that aside, the fact that people seem to believe that Jodorowsky’s quest, while never ending in an actual movie, somehow contributed to the face of sci-fi cinema being changed going forward… it’s preposterous.

On top of all that, having to listen to Jodorowsky butcher the English language only makes everything worse.

@15 – Lisamarie: Of course, he deserves a pass because he’s from the 1800s… what? 1970s? Oh, sorry, don’t mind me. :p

@17 – Eduardo: In this case, both the author and what he planned to do with Dune are complete and utter crap. Also, I am perfectly happy about boycotting material from certain authors based on their personal politics. For example, Orson Scott Card contributes financially to anti-LGBTQI* lobby groups, and if I buy one of his books or pay to see a movie based on them, it’s the same as contributing to those groups myself.

@21 – Gerry: And that, beyond any of his personal crimes (which I in no way want to diminish), is what would have made this a horrible Dune version.

@25 – Loungeshep: Yes to all you said.

@28 – Aidian: There is still the problem of using “rape” as a metaphor for anything that could remotely produce something positive and of value. It’s almost like “Christian” conservatives considering rape a blessing if it produces a child.

@30 – MattfromPoland: “Feminist” means advocating equal rights for all genders. You don’t like that, apparently.

@31 – cecrow: Then again, Jagger has consumed industrial quantities of recreational chemicals.

@34 – Latro: His Dune would have been Dune without Dune too.

@35 – Amaryllis: While I don’t condone it (see above), I actually understand what Jodorowsky is trying to say in that particular case of his use of this analogy. I think he’s actually talking about “tearing down the image of the white-clad, pure bride”, in order to “have sex with the woman and conceive a child”. Of course, as I have just shown, one can do that without using a rape analogy.

@47 – blatanville: Hahaha… reminds me when I was a little kid and me and my friends wanted to invent a super effective ant poison. Of course, the main ingredient was always water.

@50 – kimberlyr: Vader visits Arrakis because it reminds him of Tatooine. :)

@51 – David: Probably somebody’s wife.

@57, I’m a Christian conservative and I think that rape is a heinous act no matter the result. Horrible things should happen to rapists.

Also, I’m just curious, would you be willing to purchase a used copy of an Orson Scott Card book? This way there would be no money going toward the causes you object to.

(not trying to be confrontational, I’m just curious)

Thanks for the article Emily. Glad to have found there are two sides to this much talked about screenplay.

@58 – Jason: Please notice my use of quotations around the word Christian. I’m referring to a certain type of “Christian” who behaves nothing like a Christian is supposed to.

And I might buy a used copy of an Orson Scott Card book, yeah. I don’t think it’s very likely, but it’s not impossible.

The movie likely would have been successful had it been made. After all, 2001 became a major success due to viewers who would take LSD before screenings and trip put during the film.

His views are a bit whacky though.

To the one who said he saw nothing good from Moebius. In Europe a lot of people consider him as one of the greatest comic artists ever and he was GREAT. Personally I think he made his greatest work signed as Jean Giraud (Blueberry). Jodorowsky’s Dune sounds like a great movie and I would have loved to see the movie. But we never got it unfortunately. Instead we got Alien, Blade Runner, Star Wars etc. which are all inspired by Jodorowsky’s Dune. And we also got the comic “The Incal” by Jodorowsky and Moebius. We got a few Dune movies, but unfortunately none of them are great. We will probably never get the Jodorowsky’s version, but now we at least will get the Villeneuve’s version of Dune. I really hope that it will be almost as good as the book which is a master piece.

I remember having several distinct emotions while watching the documentary.

1. I think the reaction I was meant to have, which lasted for about the first quarter of it, was wondering “what if” and thinking how cool this would’ve been.

2. Into the second third, I grew perplexed, and started wondering: why did this guy seem to have absolutely zero interest in any of the actual themes of Dune? How did he think anyone was going to produce what appeared to be a bloated homage to his own (very familiar Catholic-teenaged-boy, IMO) repressed erotic obsessions masquerading in sci-fi costume? He in particular has this obsession with things “exploding” and “growing” that doesn’t need much reading-into. I was starting to cringe. I had never really heard much about this supposed mastermind and was beginning to understand why.

3. By the time he got to talking about “rape” I had checked out. I wish I could say I was shocked by that, but it was already of a piece with everything I’d seen to that point. By the time I switched it off, I *was* rather glad we never saw Jodorowsky’s Dune. I see now that he’s since walked back the claim about raping his co-star in Fando y Lis, but his obsession with rape isn’t surprising. It turns out to come up in all sorts of interviews he does.

The overall impression I was left with was of the kind of distasteful-but-charismatic chancer who all too often is able to play off his worst impulses as profundity for the art world. I’m perfectly happy his “Dune” vision never saw the light of day.

I primarily know Jodorowsky from his truly amazing collaborations in French comics with artists like Mobeus and many, many others. I recommend The Incal for any fan of science fiction (and see how that story has been borrowed from by movie makers over the years). And if by some miracle you can get your hands on a good copy of The Airtight Garage, count yourself blessed.

That said, if we judge not by the standards and practices of the era he was working in but by his other work in film, I’m sure Dune would have been a barely intelligible mess as a story, at least to the audiences of today who are less likely to use chemical enhancement while viewing. I would have paid to see it though, just for the great artists who were lined up to participate in it. Say what you want about the man and his ego, but it’s undeniable that when he worked with great artists,, he had a way of bringing out the best in them.

Most seem to not get that Jodorowsky is in part French. He has a terrible way to express his art in English, with little to no nuance. A bit like JCVD trying be philosophical in a 2nd language. Rape in french is Viol. Which has both the meaning of rape or just transgressing (in general). So a person saying “I was violated” in French does not necessarily mean it was sexual in nature (could just mean that she was robbed).