Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

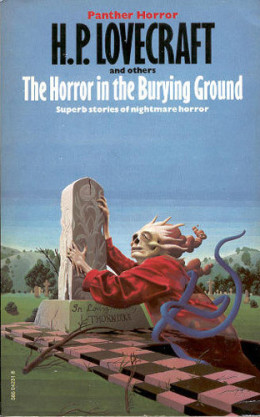

Today we’re looking at Lovecraft and Hazel Heald’s “The Horror in the Burying Ground,” first published in the May 1937 issue of Weird Tales. Spoilers ahead.

“Not much is left of Stillwater, now. The soil is played out, and most of the people have drifted to the towns across the distant river or to the city beyond the distant hills. The steeple of the old white church has fallen down, and half of the twenty-odd straggling houses are empty and in various stages of decay. Normal life is found only around Peck’s general store and filling-station, and it is here that the curious stop now and then to ask about the shuttered house and the idiot who mutters to the dead.”

Summary

Travelers taking the Stillwater road to Rutland, Vermont, may notice a certain tightly shuttered farmhouse and a white-bearded man who frequents the Swamp Hollow burying ground, chatting with its “residents.” Stillwater’s barely more than a ghost town these days, but a visitor who stops at Peck’s general store can learn something from the shabby loungers.

Sophie Sprague lives in the shuttered house, a recluse since her brother Tom and her admirer Henry Thorndike died. Crazy Johnny Dow, the graveyard loiterer, often shouts at her that something’s coming to get her. See, Tom Sprague was a big brutish fellow and a heavy drinker, who cowed his sister with threats. He hated Thorndike, a city man who’d studied medicine but settled for becoming an undertaker. An odd undertaker, too, from the queer books he read and chemicals he mixed and experiments he performed on animals. Once Tom found him with a purloined (and apparently dead) calf, and punched him out over it. Later he saw the calf alive, so he must have been wrong about its demise. Henry cordially returned Tom’s hatred.

One June day, Tom returns home from an alcoholic bender to find Henry with Sophie. Shouts erupt. Then Sophie runs for old Doc Pratt, for Tom’s heart has given out. It’s a bit suspicious that Henry stands over the dead man’s bed, ready to embalm him and bragging about what a great job he’ll do, and good thing Stillwater has him, because sometimes people do get buried alive, you know. Crazy Johnny Dow arrives to assist his employer Henry and make helpful remarks about how the corpse isn’t cold, how its eyelids twitch. As Henry pumps in embalming fluid, the corpse convulsively sits up and stabs Henry with the embalming syringe, injecting him with a hearty dose of his own medicine. Haha, says crazy Johnny. Now Henry will get dead and stiff like Tom Sprague, but remember, the injection doesn’t work as fast if the recipient doesn’t get much.

Tom’s funeral is two days later. Sophie tries to look grief-stricken, but her attention wanders from Tom’s unnervingly rosy corpse to the feverish Henry. Crazy Johnny babbles that Tom can hear and see, and they’ll bury him that way. A woman faints at the “way [Tom] looks.” In the excitement, Henry’s knocked down. He’s too sick to rise. It’s due to the accidental injection of embalming fluid. They must wait, he says—he’ll come to later, he doesn’t know how long. Meantime he’ll be conscious and aware—don’t be deceived—

He collapses, and Doc Pratt pronounces him dead. Johnny flings himself on Henry’s corpse, pleading for the crowd not to bury him. He’ll come back good as ever, but if he’s under the earth, he won’t be able to scratch his way free. It’s all right if Tom is trapped underground, though. Johnny doesn’t like Tom.

Momentarily evicted, Johnny returns to terrify Sophie by shrieking that she knows, she knows, but even so she’ll let the two men be buried alive. Never mind. They’ll still talk to her, appear to her, and one day they’ll come back and get her!

Another coffin’s produced, another grave’s dug, and Tom and Henry are laid to rest in Swamp Hollow. Johnny tries to dig them back up, but he’s put in the town jail. That night, screams from Sophie’s house draw neighbors. She’s hearing voices from Swamp Hollow. The neighbors do too, but they tell themselves it must be crazy Johnny escaped from jail. Next day the constable insists Johnny was in his cell all night.

Some people tell stories about noises in the burial ground every anniversary of the double death. Some say every black morning at two a.m., faint figures try Sophie’s doors and shuttered windows.

“She-devil,” one of the graveyard voices said that first night. And “you know.” And “comin’ again some day.”

Travelers generally leave at this point. Especially if it’s grown dark, they avoid looking up at the shuttered house or into the unquiet burial ground.

What’s Cyclopean: “Eldritch horror and daemoniac abnormality.” That’s as good a five-word summary of the Mythos as anyone could ask for.

The Degenerate Dutch: Nobody here this week but us rural New Englanders.

Mythos Making: There are a lot of places in the Mythos where experimenting with resurrection turns out to be a really bad idea. Does Henry Thorndike corresponds with Herbert West and/or the old doctor from “Cool Air”?

Libronomicon: Any bets about what grimoire the recipe for that “embalming fluid” came out of? Or eventually ended up in?

Madness Takes Its Toll: There’s no need to listen to crazy Johnny Dow, just because all the evidence backs him up. Just lock him in a shed.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Oh, Hazel. I love Hazel Heald so much. This isn’t even one of her best collaborations with our friend Howard—the gonzo cosmic scope and cyclopean record of “Out of the Aeons” retains its place in my heart—but it’s still a pitch perfect bit of American Gothic horror.

Heald always manages to smooth over Lovecraft’s jagged edges, punch his strengths and eccentricities up to 11, and add telling details that help even typed characters ring true. Lovecraft’s oeuvre contains many, many stories of rural horror. In most of these, fear is mixed with or even overshadowed by contempt. To Lovecraft, the rural poor presage what the urban rich might degenerate to (and are in many cases the descendants of once-noble families). Their dialects and gossip are alien to him, and he inevitably holds them at a remove. But in Stillwater, the monologuing report comes with interjected body language, details of scent and texture, that for me bring it close. “The listener” is by implication the reader, and you can practically smell the creepy old men and women telling their stories on the rotting porch. You want to tear yourself away and yet want to hear the tale to its end.

This manages, too, to get across the core of the rural gothic. Small towns may be tight-knit communities—but they knit around the holes in stories, the violence heard through closed doors, the missing stairs that everyone knows to avoid. It’s thoroughly plausible to fill one of those gaps with horror that’s a trifle less mundane. And it works best if not all of those gaps are so filled. Stillwater gossips know dozens of secrets, from domestic violence to drug abuse to suspected murder. Why not add a resurrected ghoul or two haunting the graveyard.

Sophie, nearly as silent as Asenath, is at the heart of everything. Hostage to her brother’s abuse, desperate enough for rescue to “make up with” whatever cad is willing to brave his inebriated temper. When she gets the chance, she wields her silence as a weapon to rid herself of both men. Or try, at least. Her neighbors are passive—complicit if sympathetic to her original mistreatment, then complicit in her method of ending it, simply through their unwillingness to name barely veiled truths.

Other Lovecraft stories include this type of all-too-plausible denial. “The Color Out of Space” is a prime example, one where problems are ignored as much to preserve the pride of those facing them as the equilibrium of potential witnesses. Ephraim Waite benefits from a similar apathy. While the direction of the abuse isn’t obvious from outside Asenath and Edward’s marriage, the fact of it sounds fairly blatant. The story, though, never much acknowledges this, nor the lacuna of Asenath’s own point of view. “Burying Ground,” presumably thanks to Heald, is rather more self-aware. And aware that the horror it reports is Sophie’s horror.

Not only Sophie’s, though. Stillwater as a whole seems to have reached some tipping point of unspeakability. It’s collapsing, slowly, around the holes left where we don’t talk about things. All that’s left are Ishmaels and albatross-laden mariners, telling the tale to every visitor who triggers their geasa. At least, unlike those prototypical isolated survivors, the porch-dwellers have each other for company.

And you, for as long as you’re willing to stick around and listen. Maybe there’s more they could tell you, if they had a mind.

Anne’s Commentary

Bad things can happen in urban cemeteries. You know, like the disinterment of Joseph Curwen or the robbing of ancient cursed amulets. But rural cemeteries are always bad news—take that abandoned one in central Florida that Randolph Carter and his soon-to-be late buddy explore. Or that one where the receiving vault really needed a new lock, lest careless undertakers get trapped inside with the disgruntled dead. Or the one from which the Outsider climbs for his unfortunate rendezvous with a mirror.

Actually, for Lovecraft, rural areas in general resonate with eldritch horror. For someone in love with old New England, he harbors a surprising antipathy for its Puritan heritage. Sure, nasty Puritan era vibes persist in Providence and Kingsport and Arkham, but they are most concentrated in the backcountry, most unadulterated by modern rationalism. Isolation fosters decadence of a low-minded, hopeless sort unlike the well-read ecstasies and dark aesthetics of the city decadent. It produces horrors like Dunwich and the Martenses, hick wizards like Old Man Whateley and Daniel Morris, the maker of stone men, and dogs, and wives. It allows unnaturally old men to brood over pictures until they decide to emulate the cannibal butchers pictured. Even stout farmers like Nahum Gardner can be overcome by colors out of space. Even outback nobility like Henry Akeley can be defeated by the Fungi that lurk in the woods. Speaking of Akeleys, it looks like one branch of the family settled in Stillwater, only for Mrs. Akeley to lose her cat to Thorndike’s impious experiments.

Those rurals. The long linger of stern Puritan theology drives them not to godliness but to incest and murder and a generalized moral torpor symbolized in both “Dunwich Horror” and “Burying Ground” by dilapidated church steeples. It also makes them superstitious. The really interesting thing is that the mumbling grandmothers at hearth-sides and maundering unkempt loiterers at general stores are RIGHT to be credulous of such horrors as Yog-Sothoth worship and postmortem vengeance and cannibal monsters that stalk under cover of thunderstorms. The veils between worlds may grow hazardously thin in the lonely countryside. Sentinel Hill ain’t crowned with a gateway of stone for nothing. Yuggothians find ample places to hide in the remote hills of Vermont.

Mad scientists are also drawn to rural privacy. Herbert West first sets up shop in an old farmhouse outside Arkham. Joseph Curwen moves his nefarious operations from Providence to the Pawtuxet valley farmland. And “Horror in the Burying Ground” gives us Henry Thorndike, undertaker extraordinaire with a sideline in reanimation worthy of his fictional predecessor West.

Lovecraft and Heald play very well together in two settings: the museum and the crumbling countryside. It looks like “Burying Ground” is the latest of their collaborations, a bit of a mishmash of their favorite tropes. As in “Man of Stone,” there’s an abusive relationship into which a second man comes, bringing the woman hope of escape. There we saw husband (a wizard), put-upon wife and wife’s lover. Here we see brother, put-upon sister and sister’s suitor (a wizardly mad scientist.) I’m thinking this character dynamic comes from Heald, along with the way the abused woman gets at least partial revenge. Though “Man of Stone’s” Rose dies, she gets to force his own medicine down her husband’s throat, and we can hope her last scrawled wish to be buried alongside her lover, statue by statue, is obeyed. “Burial Ground’s” Sophie, it’s strongly implied, is in on the temporary murder of her brother and his more horrible true death when he wakes in his buried coffin. It’s also implied that she never has loved her rescuer Henry and is only too glad when he’s impaled on his own syringe and buried alive along with Tom—all the trouble of shaking Henry has been spared her, and she can enjoy the Sprague house and money alone or with a later mate of her choice.

So far we have the magic of “Man of Stone” opposed to the pseudoscience of “Burial Ground,” although one could think of Mad Dan’s magic as that famous science so far advanced that it looks to us like magic. If we do think of it that way, “Man of Stone” fits better in the “naturalistic because super-scientific” tradition of the Cthulhu Mythos. Plus it features the Book of Eibon. Whereas “Burial Ground” starts off with pseudoscience and then becomes frankly supernatural, with ghosts outside Sophie’s shuttered windows, threatening to become more potent revenants in the future. Not that pseudoscience and the supernatural can’t coexist, but here I’m not sure they do so comfortably.

Though crazy Johnny is a cool and even sympathetic character, I find “Burial Ground” less aesthetically cohesive than “Man of Stone” or the two “Museum” collaborations. I’m iffy about poor Sophie’s lifelong (if not longer) punishment, too. On the one hand, if she was as complicit in brother Tom’s fate as implied, she can’t claim Rose’s essential innocence. On the other, Tom was a major jerk. Could be Sophie’s greater sin was not rescuing Henry from being buried alive. Still, he was a jerk, too.

Compared to the firsthand accounts in Heald’s other collaborations with Lovecraft, “Burial Ground” is static. The narrator is indeterminate—maybe he’s one of the travelers who stopped in Stillwater to hear the tale of Tom and Sophie and Henry, maybe not. The overall effect is of a thirdhand account, what happened to the principal actors filtered through various townsfolk, filtered through a nebulous traveler or travelers. Immediacy is lacking, and so the real shivery horror of premature burials and revengeful ghosts abetted by a wise idiot. Contrast the “shiver” level of this story with “Shadow over Innsmouth.” In “Innsmouth,” the narrator learns all about the eerie town and its (his!) sinister heritage on his own, doing his own footwork as it were. We don’t just hear about his “wise idiot” informant, Zadok Allen—we get to meet and sit with Zadok, as the narrator himself conducts the revelatory interview, to the sound of waves and the smell of stranded sea refuse—and maybe more.

Bottom line, I guess, this is a story compacted as much as possible, and not to its benefit. It’s the product of three years, 1933-1935, and those years near the end of Lovecraft’s productive life, which may explain some loss of narrative vigor. Lovecraft was also at work on “Shadow Out of Time” during this period. I can certainly forgive him for devoting more energy to that than to this slight tale.

Next week, we check out a modern take on Lovecraft’s “The Hound” in Poppy Z. Brite’s more impressively titled “His Mouth Will Taste of Wormwood.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.