In adapting Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, Stanley Kubrick’s ambition, as he expressed to Clarke in his introductory letter, was to make “the proverbial good science fiction movie.” That was in 1964, some years before the rehabilitation of genre cinema’s reputation by the critical establishment, a huge element of which was the movie the two gentlemen would end up releasing in 1968. With no exaggeration whatsoever, it is a simple fact that science fiction cinema would not exist in the form it does today without 2001.

The movie itself was not simple in any way. Kubrick’s initial interest in making a movie about extraterrestrials ended up evolving into nothing short of a story about humankind’s evolution from ape, to a point in the foreseeable future—one which we, in many ways, are living in now—where humans exist in a state of symbiosis with the technology they created, and where the possibility that one of those creations may surpass humanity in its humanity, and from there move to a point where, as Kubrick put it, they evolve into “beings of pure energy and spirit… [with] limitless capabilities and ungraspable intelligence.” This kind of ambition, and the amount of money Kubrick intended to spend realizing it, was unknown to science fiction cinema at the time. But, of course, Kubrick wasn’t particularly interested in doing something others had done before.

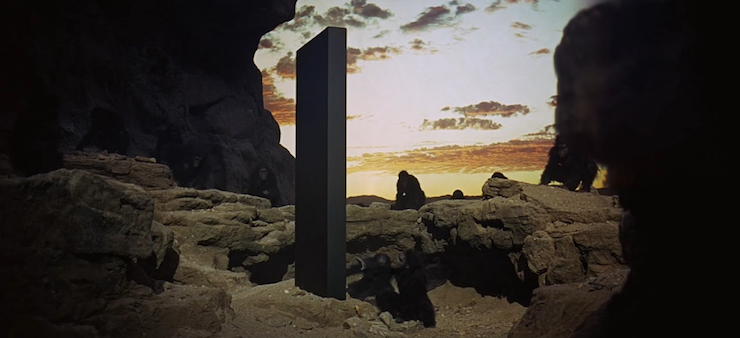

That spirit of innovation extends to the picture’s structure, which favors four distinctly separate episodes that lead to the next, rather than the usual three acts. In the first, titled, “Dawn of Man,” we’re introduced to a tribe that are a bit more than apes but not quite human yet. Their existence is a little bleak, consisting mostly of being eaten by leopards and being driven off the local muddy water hole by a louder tribe of ape/humans, until one morning they awake to see that a large black monolith has appeared. This, as one might imagine, changes things, and sets events in motion that lead us to the gleaming spacecraft orbiting Earth and shuttling people back and forth to the Moon.

The next chapter, millions of years later, finds us in space, where humanity become a bit less hairy and more talkative. We meet Dr. Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester), an American scientist on his way to the Moon on a mission shrouded in a bit of secrecy. The journey is pleasant, full of Strauss’ “Blue Danube” and long, lingering shots of the technological marvels humanity has wrought, eventually leading to the revelation that what’s really going on is that we’ve found another black monolith that was deliberately buried several million years prior (probably around the same time the other one was left on Earth). Once the monolith sees its first sunrise, it emits a loud, piercing, sustained note, that deafens Floyd and the other present scientists.

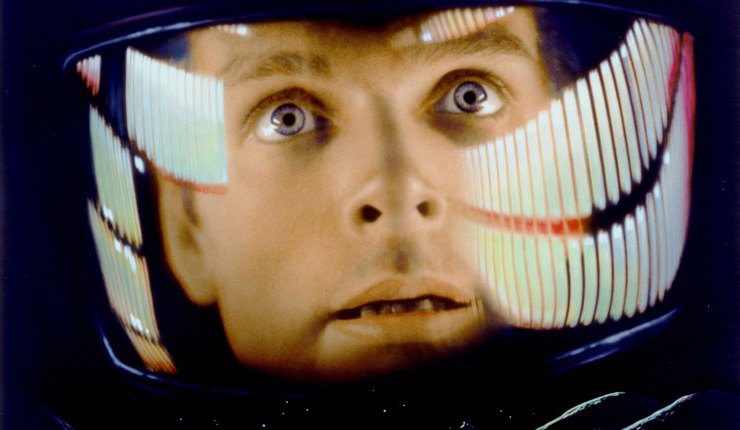

This leads to the next episode, where a manned mission to Jupiter is in progress. Our crew consists of the very taciturn astronauts Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood), three hibernating scientists, and the ship’s computer, HAL 9000.

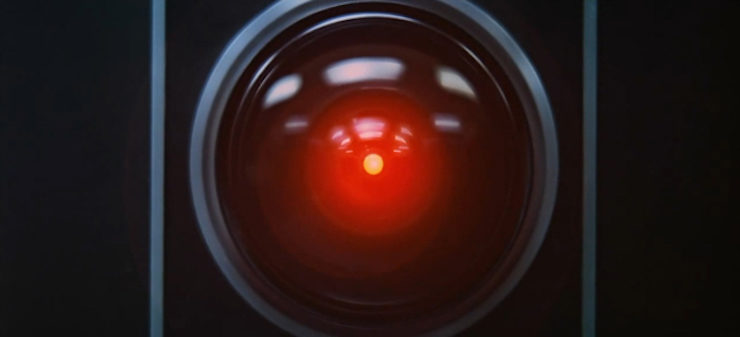

(Brief aside: HAL 9000 is the coolest computer to ever exist, and a very important milestone in the history of SF movie computers. He combines the “big with lots of flashing lights” archetype of 50s SF cinema—which established a truism that holds to this day, to wit, the more flashing lights it has, the more powerful a computer is, both in movies and life—with a very modern tendency to get overwhelmed and freak out; as a sub-aside, whoever starts and successfully maintains a fake HAL 9000 Twitter a la Death Star PR or the thousands of Dalek ones one will win my undying love.)

Everything is going fine until HAL misdiagnoses a fault in the unit that makes it possible for the spaceship to communicate with Earth. Bowman and Poole grow worried at how HAL might react, and with fairly good cause, as HAL proceeds to… well, not take their distrust very well. Bowman is eventually the last man standing, and manages to disconnect the part of HAL that gets paranoid and has nervous breakdowns. At this point, a pre-recorded message from Dr. Floyd activates, informing Bowman of the ship’s true mission: the monolith’s signal was sent to Jupiter, and they are to investigate why.

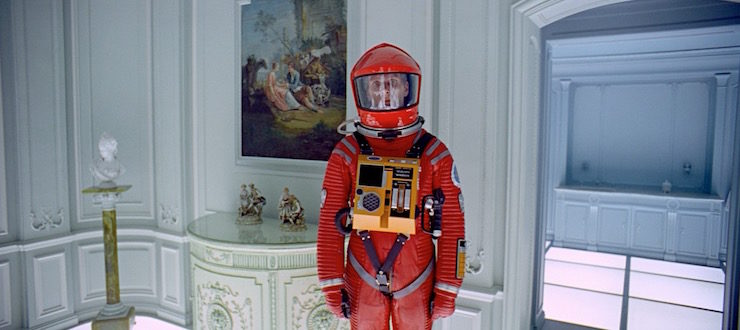

In the movie’s final chapter, Bowman arrives at Jupiter and finds another, much larger monolith, and dutifully goes to investigate. What happens next is a bit difficult to describe literally, and open to a number of different interpretations. Rather than attempt to describe or analyze it, I’ll say that it represents another step in evolution, to the level of whomever it was who built and placed the monoliths, if indeed that was all done by an entity similar enough to humanity and existing in the same physical universe that they build and place things. It all makes more sense the way Kubrick lays it out.

2001 is an absolutely tremendous film, one of the best and most innovative ever made, and widely hailed as such. A number of its champions make the slight mistake of referring to it as “surreal,” though. The picture makes perfectly logical, linear sense, even if that takes several viewings to ascertain. The first three chapters, while short on dialogue and long on meticulously constructed, geometrically precise camera shots highlighting humanity’s evolving relationship with technology, are all fairly straightforward in terms of story. Sure it’s loaded with signs and signifiers every way you look, but it all takes place in a real—if extrapolated several decades into the future and largely set in outer space—world. Even in the concluding sequence, with all the bright colors and weird images, what’s happening makes logical sense, at least the way I read it: an attempt by the aliens, whoever they are, to establish a means of communicating with Bowman. The images, gradually, become more and more familiar to human experience, concluding with some oddly colored but distinctly recognizable helicopter shots of Earth desertscapes, before arriving at the fully realized, three-dimensional simulation of a hotel room in which the aliens hurry Bowman through the last several decades of his corporeal life, before he becomes one of them, and one with them. The last shot of the movie, where this unearthly creature contemplates Earth, underscores the length of the journey he, the audience, and humanity itself has taken.

Anyway. I could go on for days talking about 2001. Many before me have, many after me will. It’s a genuinely great and important work of art. Its impact on SF cinema was indescribably vast. Not only did Kubrick and his crew essentially invent modern special effects (and, 43 years after its release, 2001‘s visual effects are still as cool as anything put on screen), but 2001‘s enormous cost and several times more enormous commercial success—I once wrote that “there has never been a weirder commercial hit in the history of cinema” than 2001 and I stand by that—led to the obsolescence of the way of thinking, explicated by legendary Hollywood executive Lew Wasserman to Kubrick when he passed on 2001, “Kid, you don’t spend over a million dollars on science fiction movies. You just don’t do that.” Thanks to the success of Kubrick and his team of collaborators (many of whom went on to cement SF cinema’s place at the table in Hollywood by working on George Lucas’ Star Wars), spending over a million dollars on science fiction movies became something you did do.

I’d characterize giving an entire genre legitimacy as a good day at the office. Even if that day took four years and meant going several hundred percent over budget. But show me someone who can make an omelet without breaking a few eggs and I’ll show you one of those camera-shy aliens who run around putting black monoliths all over the universe.

Originally published in November 2011.

Danny Bowes is a New York based critic, journalist, and blogger whose work has appeared in Premiere, The Atlantic, Indiewire, Yahoo! Movies, and Tor.com. You can read more of his work on his blog.