At first glance, Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965) might appear to be a mere copy of the story of Lawrence of Arabia with some science-fictional window dressing. Several critics have pointed to the similarities between Lawrence and Paul Atreides—both are foreign figures who immerse themselves in a desert culture and help lead the locals to overthrow their oppressors.

The 1962 film based on a romanticized version of Lawrence’s journey, Lawrence of Arabia (directed by David Lean), was critically acclaimed and widely popular. It rested on the idea of the ‘white savior,’ whose role was to lend a sympathetic ear to oppressed peoples and provide assistance to improve their lot in life. Released at a time when U.S. relations in the Middle East were becoming more complicated and the Cold War was reaching new heights of tension, this offered a potentially reassuring message that Western involvement in foreign affairs could be heroic and therefore welcomed.

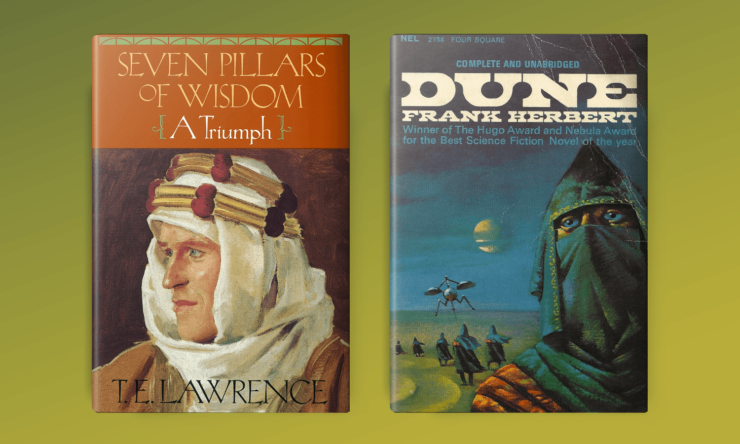

Herbert himself was very interested in exploring desert cultures and religions. As part of his extensive research and writing process, he read hundreds of books, including T.E. Lawrence’s wartime memoir, Seven Pillars of Wisdom: A Triumph (1926) [Brian Herbert, Dreamer of Dune, Tom Doherty Associates, 2003] He saw messianic overtones in Lawrence’s story and the possibility for outsiders to manipulate a culture according to their own purposes. [Timothy O’Reilly, Frank Herbert, Frederick Ungar Publishing, 1981]

Yet, although Lawrence’s narrative was certainly an inspiration for key aspects of Dune, there are also critical contrasts in the portrayals of Lawrence and Paul, the Arabs and the Fremen, women, and religion. What follows is a discussion of some similarities and differences between the fictional world of Dune and the worlds in Seven Pillars of Wisdom as filtered through Lawrence’s recollections of his time as a go-between figure in the British and Arab camps during World War I. This overview will demonstrate how Herbert adapted and modified elements of Lawrence’s story to create a world in Dune that is both familiar and new.

Introducing Lawrence

The subject of over 70 biographies and multiple films, plays, and other writings, T.E. Lawrence is a household name for many in the West. [Scott Anderson, “The True Story of Lawrence of Arabia,” Smithsonian Magazine, 2014] He was an officer in the British Army during WWI who served as an adviser to the Arabs and helped in their revolt against the Turks, though the extent of his influence is disputed among historians. [Stanley Weintraub, “T.E. Lawrence,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2020] Other figures, such as British archaeologist and writer Gertrude Bell, were better known at the time and arguably had a greater impact on Middle Eastern politics. [Georgina Howell, Queen of the Desert: The Extraordinary Life of Gertrude Bell, Pan Books, 2015] But after American journalist Lowell Thomas seized upon Lawrence’s story in 1918, Lawrence’s fame grew to eclipse that of his contemporaries.

Interestingly, whether or not others consider Lawrence of Arabia to be a hero, Lawrence does not portray himself that way in Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Instead, he appears as a conflicted man, trying to bridge two worlds but feeling like a fraud. On the one hand, he explains the ways in which he becomes like one of the Arabs: in dress, in mannerisms, and in the ability to appreciate desert living. He takes some pleasure in being hardier and more knowledgeable than his fellow British associates.

On the other hand, there are varying degrees of contempt in his descriptions of the Arabs and their differences from the British. Filtering his experiences through his British sensibilities creates a sense of superiority at times that adds to the cultural barrier he faces. Although Lawrence himself may have been accepted and respected by his Arab companions, the image of Lawrence of Arabia is problematic for its implication that native peoples need a ‘white savior’ to rescue them from their oppression.

This continues to be a topic of debate in relation to Dune, as shown, for example, in Emmet Asher-Perrin’s Tor.com article Why It’s Important to Consider Whether Dune Is a White Savior Narrative.

Lawrence of Arabia

Both Lawrence and Paul appear to be men raised in Western cultures who adopt the ways of a Middle Eastern culture in order to blend in and meet their goal of rallying a fighting force to meet their own (imperial) goals. They understand the importance of desert power and act as a bridge between the two worlds they inhabit to facilitate the use of this force.

Looking first at Lawrence, he admits early on that his book is not a history of the Arab movement but of himself in the movement. It is about his daily life and encounters with people, with the war providing a sense of purpose to structure the narrative. In short, this purpose is to convince enough Arab tribes to side with Prince Feisal against the Turks to defeat them. It means persuading the tribes to put aside their grudges and vendettas, and sometimes their ways of tribal justice, to form a cohesive front.

Lawrence already knows Arabic and how to wear the skirts and head-cloth of the Arab outfit, but he gains a deeper understanding of the language and culture through his experience traveling in the Middle East. For example, he discovers how important it is to have a broad knowledge of the various peoples who live in the desert if one wants to be accepted as an insider: “In the little-peopled desert every worshipful man knew every other; and instead of books they studied their generation. To have fallen short in such knowledge would have meant being branded either as ill-bred, or as a stranger; and strangers were not admitted to familiar intercourse or councils, or confidence.” [Lawrence, p 416-417*] He is used to book knowledge being valued. Now he must adjust to picking up information tidbits to gain the trust of new tribes and persuade them to his and Feisal’s cause.

In terms of clothing, Lawrence comes to accept the Arab dress as “convenient in such a climate” and blends in with his Arab companions by wearing it instead of the British officer uniform. [Lawrence, p 111] This reduces the sense that he is from a different culture and way of life. He learns the advantages of “going bare foot” to gain a better grip on tough terrain but also the pain of having no shoe protection in rocky or snowy terrain. [Lawrence, p 486] He writes of the incredulity of Egyptian and British military police in Cairo when he answers their questions in Arabic with fluent English: “They looked at my bare feet, white silk robes and gold head-rope and dagger…I was burned crimson and very haggard with travel. (Later I found my weight to be less than seven stone [44 kg/98 lb]).” [Lawrence, p 327-328] Here Lawrence paints a picture of himself as seen through their eyes—a scrawny, sunburned, barefoot leader dressed like an Arab but speaking English like a British person.

Sometimes his transformation leads to feelings of shame, showing Lawrence’s discomfort with the idea that he has ‘gone native.’ At the close of the book, once Damascus has been conquered, he has an unusual encounter with a medical major:

With a brow of disgust for my skirts and sandals he said, ‘You’re in charge?’ Modestly I smirked that in a way I was, and then he burst out, ‘Scandalous, disgraceful, outrageous, ought to be shot…’ At this onslaught I cackled out like a chicken, with the wild laughter of strain…I hooted out again, and he smacked me over the face and stalked off, leaving me more ashamed than angry, for in my heart I felt he was right, and that anyone who pushed through to success a rebellion of the weak against their masters must come out of it so stained in estimation that afterward nothing in the world would make him feel clean. However, it was nearly over. [Lawrence, p 682]

While the medical major is disgusted at Lawrence’s Arab appearance and thinks he has sullied himself, Lawrence seems to feel ashamed of having taken on this appearance as a way of manipulating the Arabs to rebel. He feels dirtied by his role but knows that his part in this performance is almost over.

The strategic advantage that Lawrence identifies is that the Arabs are on their own turf and can engage in guerilla-style attacks, then retreat into the desert with minimal casualties. Throughout Seven Pillars, Lawrence describes how he led small groups of men to sabotage the Turks’ transportation and communication networks by installing explosives in key parts of the railway such as bridges. Their ability to quickly maneuver on camels and disappear made them difficult targets to anticipate or defend against. He makes a comparison between this ‘desert power’ and naval power, which the British were very familiar with:

‘He who commands the sea is at great liberty, and may take as much or as little of the war as he will.’ And we commanded the desert. Camel raiding parties, self-contained like ships, might cruise confidently along the enemy’s cultivation-frontier, sure of an unhindered retreat into their desert-element which the Turks could not explore. [Lawrence, p 345]

As a fighting force, the camels were also formidable. Lawrence says that “a charge of ridden camels going nearly thirty miles an hour was irresistible.” [Lawrence, p 310] Another advantage was that the Arabs’ numbers were constantly in flux due to a reliance on a mixture of tribes rather than one main armed force. This meant “No spies could count us, either, since even ourselves had not the smallest idea of our strength at any given moment.” [Lawrence, p 390] Lawrence’s narrative shows his appreciation for this way of waging war and how much his thinking adapts in response to his new environment.

Paul Muad’Dib

How does this picture of Lawrence transformed into Lawrence of Arabia compare with the characterization of Paul Atreides in Dune?

Paul is also raised in a Western-like style yet able to adopt the ways of a foreign people with relative ease. He is curious about the “will-o’-the-sand people called Fremen” even before he moves from Caladan to Arrakis. [Herbert, p 5*] Once there, he relies on his training as the son of a duke and a Bene Gesserit to understand and adapt to the local culture.

Paul somehow knows how to properly fit a stillsuit on his first try, as if it were already natural to him. His knowledge and intelligence impress the Imperial Planetologist Dr. Liet Kynes, who believes Paul fits with the legend: “He shall know your ways as though born to them.” [Herbert, p 110] Compare this with a passage from Seven Pillars: “Now as it happened I had been educated in Syria before the war to wear the entire Arab outfit when necessary without strangeness, or sense of being socially compromised.” [Lawrence, p 111] Unlike Lawrence, Paul has the advantage of his growing prescience to give him special foreknowledge of how to adjust to his new environment, as well as a savior narrative to align with. But both are able to take on the garb of a different culture relatively smoothly.

Besides dress, their outward attitude toward the foreigners they find themselves among is similar. Lawrence states idealistically that “I meant to make a new nation, to restore a lost influence, to give twenty millions of Semites the foundation on which to build an inspired dream-palace of their national thoughts.” [Lawrence, p 23] Once among the Fremen, Paul is named Paul Muad’Dib and Usul and learns how to live according to their cultural norms and values. He presumes to help train and lead the Fremen so they can fight against their common enemy, the Harkonnen, and turn Arrakis into a water-filled paradise. But both figures admit that what they actually need is a fighting force. The promise of independence they hold out is thus a means to an end.

The idea of desert power in Lawrence’s story also appears in Dune. Duke Leto informs his son, Paul, of this shift in how to maintain control of their new planet. He tells Paul, “On Caladan, we ruled with sea and air power…Here, we must scrabble for desert power.” [Herbert, p 104] Later, Paul shows that he has accepted this as his own strategy: “Here, it’s desert power. The Fremen are the key.” [Herbert, p 204] Just as the Turks were constantly stymied by the Arab attacks on their equipment and forces, the Harkonnen find themselves with severe losses due to the Fremen raids. Their underestimation of the Fremen leaves them vulnerable. By the time they acknowledge that they have been losing five troops to every one Fremen, it is too late.

Herbert gives the Fremen on their sandworms a final dramatic military maneuver when they ride in to attack the Emperor after using atomics to blow open the Shield Wall. Just like the camels that Lawrence describes create an “irresistible” charge during battle, the sandworms handily plow through the Emperor’s forces in their surprise appearance.

Compare Lawrence’s description of the camel-mounted forces surrounding him at an honor march with Herbert’s scene:

…the forces behind us swelled till there was a line of men and camels winding along the narrow pass towards the watershed for as far back as the eye reached…behind them again the wild mass of twelve hundred bouncing camels of the bodyguard, packed as closely as they could move, the men in every variety of coloured clothes and the camels nearly as brilliant in their trappings. We filled the valley to its banks with our flashing stream. [Lawrence, p 144-145]

Out of the sand haze came an orderly mass of flashing shapes—great rising curves with crystal spokes that resolved into the gaping mouths of sandworms, a massed wall of them, each with troops of Fremen riding to the attack. They came in a hissing wedge, robes whipping in the wind as they cut through the melee on the plain. [Herbert, p 464]

Both passages give a sense of the magnitude of these mounted forces prepared to do battle. They even use similar imagery: a “flashing stream” and “flashing shapes,” a “wild mass” and “a massed wall.” To any enemy who had discounted the desert dwellers as merely a pest, these mounted forces prove the error in that assumption.

Like Lawrence, by bringing new insights, training, and “skilled assistance,” Paul aids local efforts to achieve victory. [Lawrence, p 113] He also holds a more expansive vision of what can be achieved, and acts as a bridge between the worlds of the Fremen and the Imperium. This is how Paul becomes a Lawrence of Arabia figure, and the clear parallels between the desert in Dune and the Middle East only add to this sense.

Differing Emotions

Despite their similarities, Lawrence appears much more conflicted than Paul about his role in adopting the ways of a foreign people and assuming such great authority over them. His anxiety is peppered throughout Seven Pillars as he describes his attempt to inhabit two worlds.

A Conflicted Man

Lawrence admits that he is unprepared for the large role he is given in the Middle East during WWI, but out of duty or other reasons he stays the course. He says, “I was unfortunately as much in command of the campaign as I pleased, and was untrained.” [Lawrence, p 193] When he is told to return to Arabia and Feisal after believing he was done in the region, he notes that this task goes against his grain—he is completely unfit for the job, he hates responsibility, and he is not good with persuading people. His only knowledge of soldiering is as a student at Oxford reading books about Napoleon’s campaigns and Hannibal’s tactics. Yet he is still forced to go and “take up a role for which I felt no inclination.” [Lawrence, p 117]

Deeper into the 700-page memoir, Lawrence writes more specifically and frequently about feeling like a fraud and trying to serve two masters. He foreshadows his conflictions early on, believing that “In my case, the effort for these years to live in the dress of Arabs, and to imitate their mental foundation, quitted me of my English self, and let me look at the West and its conventions with new eyes: they destroyed it all for me. At the same time I could not sincerely take on the Arab skin: it was an affectation only.” [Lawrence, p 30]

Although he gains a new perspective on his own culture, he acknowledges that his role was part of a performance. He knows that “I must take up again my mantle of fraud in the East…It might be fraud or it might be farce: no one should say that I could not play it.” [Lawrence, p 515] This means having to present different faces to the British and the Arabs, and he knows the latter will necessarily suffer in the face of the former’s might. He says, “Not for the first or last time service to two masters irked me… Yet I could not explain to Allenby the whole Arab situation, nor disclose the full British plan to Feisal… Of course, we were fighting for an Allied victory, and since the English were the leading partners, the Arabs would have, in the last resort, to be sacrificed for them. But was it the last resort?” [Lawrence, p 395] In one instance, he feels homesick and like an outcast among the Arabs, someone who has “exploited their highest ideals and made their love of freedom one more tool to help England win.” [Lawrence, p 560]

The words he uses paint a dismal picture of his complicity in winning the Arabs’ trust. He believes that “I was raising the Arabs on false pretenses, and exercising a false authority over my dupes” and that “the war seemed as great a folly as my sham leadership a crime.” [Lawrence, p 387] Again he calls them “our dupes, wholeheartedly fighting the enemy” but still the “bravest, simplest and merriest of men.” [Lawrence, p 566]

It especially seems to bother him that he is a foreigner—from a large colonial power, no less—preaching to them about the need for national freedom. He states, “When necessary, I had done my share of proselytizing fatigues, converting as best I could; conscious all the time of my strangeness, and of the incongruity of an alien’s advocating national liberty.” [Lawrence, p 458] He calls himself “the stranger, the godless fraud inspiring an alien nationality” who hopes “to lead the national uprising of another race, the daily posturing in alien dress, preaching in alien speech.” [Lawrence, p 564, 514]

Such feelings prey on his mind and make him fearful of being left with his thoughts: “My will had gone and I feared to be alone, lest the winds of circumstance, or power, or lust, blow my empty soul away.” [Lawrence, p 514] He also suspects that there must be something in him that enabled such a duplicitous performance: “I must have had some tendency, some aptitude, for deceit, or I would not have deceived men so well, and persisted two years in bringing to success a deceit which others had framed and set afoot…Suffice it that since the march to Akaba I bitterly repented my entanglement in the movement, with a bitterness sufficient to corrode my inactive hours, but insufficient to make me cut myself clear of it.” [Lawrence, p 569]

But Lawrence still finds himself craving a good reputation among others and feeling guilty that he of all people should have one. He sees that “Here were the Arabs believing me, Allenby and Clayton trusting me, my bodyguard dying for me: and I began to wonder if all established reputations were founded, like mine, on fraud.” [Lawrence, p 579]

A Confident Man

The reflections on fraudulence and guilt in Lawrence’s book stand out as aspects that are mostly absent in the characterization of Paul in Dune. Paul does have some fears about his ability to prevent the jihad he foresees. But he appears fully able to reconcile his position as a duke in exile with his position as a leader among the Fremen who supposedly has their interests at heart. In comparison to Lawrence, Paul appears overly confident and unbothered by his use of foreign forces to gain authority and territorial rule.

As discussed above, Paul is explicitly told by his father about the importance of desert power. He seems to think his status entitles him to not only secure safety and survival among the Fremen, but to convince them to sacrifice themselves to help him reclaim his House’s ruling authority. And his plan is made even smoother by the fact that the way has already been paved by the Bene Gesserit’s Missionaria Protectiva for him to be accepted as a messiah figure.

Despite Paul seeing the likelihood of a terrible jihad waged by a combination of Atreides forces and Fremen warriors, there is little indication of an effort to take a different path. Paul describes how he “suddenly saw how fertile was the ground into which he had fallen, and with this realization, the terrible purpose filled him.” [Herbert, p 199] He foresees a path with “peaks of violence…a warrior religion there, a fire spreading across the universe with the Atreides green and black banner waving at the head of fanatic legions drunk on spice liquor.” [Herbert, p 199] He even seems to blame the Fremen for this at times. For example, he feels that “this Fremen world was fishing for him, trying to snare him in its ways. And he knew what lay in that snare—the wild jihad, the religious war he felt he should avoid at any cost.” [Herbert, p 346-347]

Somewhat arrogantly, he believes that he is the only one who can prevent this from happening. On the day of his sandworm riding test, “Half pridefully, Paul thought: I cannot do the simplest thing without its becoming a legend…every move I make this day. Live or die, it is a legend. I must not die. Then it will be only legend and nothing to stop the jihad.” [Herbert, p 388] On seeing the Fremen leader Stilgar transformed into “a receptacle for awe and obedience” toward him, Paul tells himself, “They sense that I must take the throne…But they cannot know I do it to prevent the jihad.” [Herbert, p 469]

Yet he, along with his mother, are the ones who train the Fremen to become even more skilled warriors, and he invites them to defeat not only the Harkonnen but the Emperor himself. Thus, Paul conveniently overlooks his own actions which directly contribute to this outbreak of violence across the universe. It is only toward the end of the book that he recognizes his role: “And Paul saw how futile were any efforts of his to change any smallest bit of this. He had thought to oppose the jihad within himself, but the jihad would be. His legions would rage out from Arrakis even without him. They needed only the legend he already had become. He had shown them the way.” [Herbert, p 482]

Whereas Lawrence reveals increased feelings of guilt during his time among the Arabs, Paul appears more and more confident, buoyed by his prescient abilities and victories over his enemies. And although both Seven Pillars of Wisdom and Dune have arguably successful endings for the peoples that have received external assistance, there is a sense that Lawrence is relieved that he can relinquish his position of authority, while Paul is triumphant at his rising power. He also displays his sense of ownership and control over the Fremen as a people, unequivocally stating that “The Fremen are mine.” [Herbert, p 489]

This represents a clear difference between these two men and how they process responsibility and authority. Paul is indeed a Lawrence of Arabia-type character, but appears to be absolved of the sense of fraudulence and guilt that Lawrence returns to again and again in his reflections.

Orientalizing Tendencies

There are also differences in Lawrence’s account of the Arabs as compared to Paul’s understanding of the Fremen. Although both use stereotypes, Lawrence’s descriptions have a greater tendency to contain Orientalist attitudes about non-Western cultures.

In brief, according to the famous Palestinian American academic Edward Said, Orientalism refers to the way that Westerners have historically set up a distinction between East and West, Orient and Occident, without acknowledging that this is a human-created construct that strengthens the power of the West. [Orientalism, Vintage, (first ed 1978) 2003] This perpetuates the idea that the West is superior to the East and reinforces stereotypes about who is civilized and who is human. In an Orientalist perspective, there is an “absolute and systematic difference between the West, which is rational, developed, humane, superior, and the Orient, which is aberrant, undeveloped, inferior.” [Said, p 300]

Said’s theory has been widely used in academic circles to analyze concepts such as imperialism, colonialization, and racism. It is also used as a lens to analyze cultural products like books, films, and advertising. Because Said specifically focuses on the Middle East and depictions of Arabs in his work, it is particularly useful in examining texts related to these.

The Arabs

Having spent extended periods of time living with various Arab groups, Lawrence is able to move past some stereotypes. As discussed above, there are certainly aspects of the Arabs that he finds beneficial. Although the living conditions can be difficult, he displays a certain amount of respect for the way the nomads, in particular, have carved out a living through use of dress, camels, wells, and other adaptations to the landscape and climate. He himself adopts their ways and language and communicates with them about complex military operations.

Certain men he describes favorably, such as Prince Feisal: “In appearance he was tall, graceful and vigorous, with the most beautiful gait, and a royal dignity of head and shoulders.” [Lawrence, p 98] Another leader he characterizes with less positive language: “Nuri, the hard, silent, cynical old man, held the tribe between his fingers like a tool.” [Lawrence, p 641]

Lawrence is more neutral in tone about his observations regarding how the Arabs organize themselves. He portrays the tribal structure and lack of hierarchy as somewhat of a double-edged sword. On the one hand, society is more egalitarian and “there were no distinctions, traditional or natural.” [Lawrence, p 161] This means that a leader must earn their position through merit and share the experiences of living and eating with those in their ranks.

On the other hand, it means that they are less likely to form the kind of large, disciplined armies that nations like Britain use for conquest and control. Lawrence explains how it takes Feisal two years to settle all of the blood feuds in the region so that different tribes can unite in war against the Turks. Because their “idea of nationality was the independence of clans and villages,” it is more challenging to ask them to view themselves as part of an Arab nation. [Lawrence, p 103]

Lawrence’s descriptions of the Arabs as a people show the type of Orientalist tendencies that Said criticizes. Lawrence claims that they are a simple people, willing believers, and undisciplined fighters who need leadership and guidance to harness their potential. He also sometimes uses the language of savagery, perhaps in an attempt to differentiate himself, whom he considers a civilized Englishman, from the tribesmen.

In his observations, it is clear he is using his own culture as a reference point: “They were a dogmatic people, despising doubt, our modern crown of thorns. They did not understand our metaphysical difficulties, our introspective questionings. They knew only truth and untruth, belief and unbelief, without our hesitating retinue of finer shades…they were a limited, narrow-minded people.” [Lawrence, p 36]

Yet their minds are fully open to belief and obedience, according to Lawrence. One of his pieces of evidence is that three of the great world religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) arose out of this region and found ways of prospering among the people.

His opinion is that “Arabs could be swung on an idea as on a cord; for the unpledged allegiance of their minds made them obedient servants. None of them would escape the bond till success had come, and with it responsibility and duty and engagements…Their mind was strange and dark, full of depressions and exaltations, lacking in rule, but with more of ardour and more fertile in belief than any other in the world.” [Lawrence, p 41]

Lawrence sees this characteristic of obedience as full of potential, but only if it can be used to establish discipline. He describes how the Arabs perform well in small units but “[i]n mass they were not formidable, since they had no corporate spirit, nor discipline nor mutual confidence.” [Lawrence, p 140] After “spartan exercises” and training, though, they can become “excellent soldiers, instantly obedient and capable of formal attack.” [Lawrence, p 141] The goal appears to be to use the men’s usual fighting style for guerilla attacks when needed, but also train them to be able to fight in a more formal style that will help the Allies.

The Fremen

There are certainly several general parallels between the cultures of the Arabs and the Fremen. A strong Arabic influence appears in Dune through the use of Arab history, topography, culture, and words. Herbert borrows substantially from Arabic with terms such as Muad’Dib, Usul, Lisan Al-Gaib, Sayyadina, Shari-a, and Shaitan. [Istvan Csicsery-Ronay Jr, Seven Beauties of Science Fiction, Wesleyan University Press, 2008, p 39; Karin Christina Ryding, “The Arabic of Dune: Language and Landscape,” In Language in Place: Stylistic Perspectives on Landscape, Place and Environment, edited by Daniela Francesca Virdis, Elisabetta Zurru, and Ernestine Lahey, John Benjamins Publishing, 2021]

Critics have pointed to an analogy between the Fremen and Bedouin Arabs due to their cultures being nomadic, using guerilla war tactics, and having to live in harmony with nature out of necessity. [Csicsery-Ronay; B. Herbert; O’Reilly] In addition, the camel and sandworm are both used for transportation, warfare, and economic and cultural needs. [Hoda M. Zaki, “Orientalism in Science Fiction.” In Food for Our Grandmothers: Writings by Arab-American and Arab-Canadian Feminists, edited by Joanna Kadi, South End Press, 1994, p 182]

The overall characterization of the Fremen may be considered an overly romantic vision of Arab Bedouin society: long, flowing robes and dark or tanned skin; the practice of polygamy; values such as honor, trust, and bravery; and tribes that live primitive and simple lives in response to a brutal environment. [Zaki, p 183]

The representation of desert peoples through the Atreides’ eyes does rely on some romanticized notions. However, it can be seen as relying on fewer negative stereotypes than the depiction of the Arabs in Lawrence’s book.

In the Atreides’ view, the Fremen appear at first to be a suspicious and cautious people, willing to see if they can work with the Atreides or if they will need to consider them hostile like the Harkonnen. In the meantime, the Fremen helpfully provide solid intelligence and gifts of value such as stillsuits. Following his father, Paul accepts the view that the Fremen could be the allies and ‘desert power’ that they need. He thus has a clear incentive to look upon them favorably, just as Lawrence does.

When he sees the Fremen Stilgar for the first time, he feels the leader’s commanding presence: “A tall, robed figure stood in the door…A light tan robe completely enveloped the man except for a gap in the hood and black veil that exposed eyes of total blue—no white in them at all…In the waiting silence, Paul studied the man, sensing the aura of power that radiated from him. He was a leader—a Fremen leader.” [Herbert, p 92] Stilgar brings with him a sense of authority that all recognize. This aligns with how Lawrence describes Feisal—with a sense of destiny: “I felt at first glance that this was the man I had come to Arabia to seek – the leader who would bring the Arab Revolt to full glory. Feisal looked very tall and pillar-like, very slender, in his long white silk robes and his brown head-cloth bound with a brilliant scarlet and gold cord.” [Lawrence, p 92]

Also similar to Lawrence, Paul comes to understand and respect the way the Fremen have made the harsh environment livable through their stillsuits, sandworm riding, and other adaptations. When he realizes that the Fremen do not fear the desert because they know how to “outwit the worm”, he is impressed. [Herbert, p 125]

He notes the difference between his world—heavily regulated by the faufreluches class system—and that of the Fremen, who “lived at the desert edge without caid or bashar to command them” and were not recorded in Imperial censuses. [Herbert, p 4-5] Like Lawrence, he appears not to mind his experience living in a tribal structure, though both men still enjoy a certain privilege as outsiders. He learns how to ride sandworms, just as Lawrence learns how to ride camels.

Along with his mother, Jessica, Paul finds success in teaching Fremen fighters how to engage in more effective attacks against the Harkonnen. Jessica realizes that “The little raids, the certain raids—these are no longer enough now that Paul and I have trained them. They feel their power. They want to fight.” [Herbert, p 399]

Yet the concept of these desert peoples being simple-minded and willing to believe anything is also present in Dune. Fremen society has been sown with the myths and legends of the Bene Gesserit’s Missionaria Protectiva, which primes them to accept Jessica and Paul as savior figures without much question. Jessica knowingly capitalizes on these legends to solidify her and Paul’s status, and Paul is pulled along into the mythos.

In comparison to these two rational-seeming figures, the Fremen can appear superstitious and trapped in their traditional ways. Their minds seem especially open to belief and obedience, in a way similar to how Lawrence describes the Arabs.

Arguably this is part of Herbert’s study of religions and his critique of people’s willingness to follow religious leaders and their promises: The Missionaria Protectiva goes out to many planets and populations, not just the Fremen. But the Orientalist overtones remain an inescapable part of the Fremen’s characterization, with ‘enlightened’ leaders needing to come to assist supposedly ‘inferior’ native peoples. The Fremen as a whole shift from independent tribal groups to commando forces operating under Paul’s guidance and religious authority. No matter how independent and authoritative Stilgar is initially, he too comes to believe in the legend and defers to Paul.

However, it is significant that the main characters themselves essentially become Fremen, even though this is out of necessity and somewhat exploitative. Just like Lawrence sees some of the Arabs’ ways as beneficial and chooses to adopt them, Paul and Jessica see the value of the Fremen’s ways in the desert environment and adopt them. They learn the water discipline necessary for desert survival. Jessica becomes a Fremen Reverend Mother and thus a key keeper of memory and advisor for the tribe. Paul accepts the mantle of messiah, new names, and a Fremen woman, Chani, as his concubine.

Basically, they both accept a hybrid identity as the new norm for their lives—a type of uniting of West and East that helps them defeat their mutual enemies. [Kara Kennedy, “Epic World-Building: Names and Cultures in Dune” Names, vol. 64, no. 2, p 106] This adds more dimension and nuance to the depiction of the Fremen and their culture, preventing it from relying solely on Orientalist stereotypes. And unlike Lawrence, who eventually returns to England, Paul remains close to the desert environment and influenced by Fremen in his role as ruler.

Women and Religion

There are two other notable differences between the worlds of Seven Pillars and Dune. One is the portrayal of women.

Lawrence’s book is clearly positioned as a man’s story about a male domain (war) likely intended for a male audience, and there are only a few mentions of women in total. Lawrence makes some brief reflections about the lack of women, but this mainly seems to be so that he can comment on the effect the absence has on men. He says the Arab leaders rely on their instinct and intuition and “Like women, they understood and judged quickly, effortlessly.” [Lawrence, p 221] He attributes this to “the Oriental exclusion of woman from politics”—that men end up taking on both so-called masculine and feminine characteristics in women’s absence. [Lawrence, p 221] He notes that “from end to end of it there was nothing female in the Arab movement, but the camels.” [Lawrence, p 221]

In contrast, women are very much present throughout Dune. A woman opens not only the book itself, but each unnumbered chapter within. This is the voice of Princess Irulan, the Emperor’s daughter, who authors the epigraphs and enters as a character at the book’s close. Irulan’s role is significant for shaping how the reader interprets each chapter. Her writings foreshadow key points and add to the sense that certain events are destined to happen.

Jessica appears so often she can be considered a main character alongside Paul. Being one of the Bene Gesserit, she is a highly skilled woman who takes responsibility for training and guiding her son, and securing their safety and survival as outsiders among the Fremen.

Chani is the child of Planetologist Liet Kynes and a Fremen woman and is introduced as a fierce fighter in Stilgar’s group that travels as a military company.

There is certainly no equivalent to these women in Lawrence’s book (or the 1962 film, which has no speaking roles for women in its 227-minute running time). Any comparisons between Paul and Lawrence of Arabia should acknowledge that Paul is not the kind of solitary hero that Lawrence is often held up to be.

The second major difference between the texts is in the portrayal of religion.

In Seven Pillars it is nearly absent. In a book so focused on the Middle East and its people and politics, one might expect some discussion of Islam and religious practices. But as Lawrence explains it, religion is not a major factor in the war the Arabs are fighting since their enemies, the Turks, are also Muslim. He says that “Of religious fanaticism there was little trace”, implying that religion would not be a helpful motivation for the Arabs in their alliance with Allied forces. [Lawrence, p 103]

Meanwhile, Dune is saturated with references to a variety of religions, including Catholicism, Islam, and Buddhism. Paul quotes the Orange Catholic Bible and receives a miniature copy of one. Jessica employs religious incantations from the Missionaria Protectiva to fit the mold of a prophesied figure, and also helps Paul capitalize on these myths. “Appendix II: The Religion of Dune” provides more background information on the different religious currents in the universe and is interwoven with references to real-world religions.

All of these references to and critiques of religion make it a significant aspect of the book. This fits with Herbert’s interest in exploring the nature of the desert environment, and specifically what has caused it to give birth to so many major religions and loyal followers. It also aligns with his warnings about the danger of superhero figures, who he believes are “disastrous for humankind.” [Frank Herbert, “Dangers of the Superhero,” In The Maker of Dune, edited by Tim O’Reilly, Berkley Books, 1987, p 97]

Conclusion

In examining Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom as a source of inspiration for Herbert’s Dune, we’ve seen that there are multiple similarities, but also significant differences between the two works. T.E. Lawrence and Paul Atreides have much in common, yet while Lawrence expresses his sense of feeling like an unprepared fraud, Paul is bolstered by his training and status to feel much more confident in his leadership. The Arabs and Bedouin tribes are indeed an inspiration for the characterization of the Fremen, and Paul has a more favorable attitude toward desert peoples than Lawrence, who exhibits more overt Orientalizing tendencies. And finally, Dune is much more concerned with including a variety of religious references and a positive portrayal of women than Lawrence, who excludes these aspects almost entirely.

What all this shows is that Dune is not in fact a copy of the story of Lawrence of Arabia with some science-fictional window dressing. Rather, it uses elements of Lawrence’s story and his unique perspective as key ingredients with which to create a new and fascinating world.

Note: Page numbers for Seven Pillars of Wisdom: A Triumph are from the Alden Press 1946 edition and for Dune the Berkley Books 1984 edition.

Kara Kennedy, PhD, is a researcher and writer in the areas of science fiction, digital literacy, and writing. She has published academic articles on world-building in the Dune series and has other works about the series forthcoming. She posts literary analyses of Dune for a mainstream audience on her blog at DuneScholar.com.

This is a very interesting article comparing and contrasting Lawrence of Arabia and Paul Atreides / Dune. For more about the writing and origin of “Dune” check out Daniel Immerwahr’s essay in LA Review of Books and/or his YouTube talk.

I never got the sense that the David Lean film was a romanticized telling of Lawrence’s story. Well, not fully. It is romanticized in the first half; it’s certainly shot as though the man could move mountains against the Turks. But by the end Lawrence has bought into his own myth and become broken and disillusioned as a result. It is about a white savior but not necessarily endorsing that viewpoint. “Let me take your bloody picture for the bloody newspapers.”

Thank you for this fascinating essay.

Herbert also copied some phrases and descriptions ( word for word) from Lesley Blanch’s

“The Sabres of Paradise” which is about the Chechen revolt against the Russians in the 19th century. Words like “ kanly”, “ kindjal” and various aspects of Fremen culture are lifted straight out of that book. I stumbled on this decades ago, before the internet and had no one to tell, but since then a few other people have written about it.

Here is a link from 2017 about The Sabres of Paradise and Dune.

https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-secret-history-of-dune/

Donald is correct in his above observations, there is MUCH more influence from “Sabres of Paradise” (a Terrific book, IMHO) than Larry of Araby, though there is some crossover. I think the author of the article needs to do a second take, if not already done so, and read SoP to reconsider/re-examine her hypothesis.

A

This is a wonderful comparison between Seven Pillars and Dune. Very well-thought-out and -argued. My one quibble would be that, though it does mention at the beginning that Seven Pillars is a memoir and Dune is fiction, memoir and fiction are fundamentally different (although it is true that they are not as far apart as some would think). T.E. is a real person, while Paul is a character, a creation of Herbert’s mind. Perhaps a bit more emphasis on the fact that Paul is Herbert’s creation? Paul can’t decide something. Herbert can write Paul to make certain decisions, but Paul the fictional character does not have agency. The cause and effect is all in Herbert’s mind. Still, this is a great essay!

I may not have learned a ton more about Dune, but I certainly learned a LOT about TE Lawrence. Fascinating.

I think there might be a misunderstanding here. You write:

But that’s not what appears to be happening in that scene from Seven Pillars. In it, a doctor comes up to Lawrence and asks “Hey, are you the person in charge of this ‘war crimes’-level atrocity of a hospital, where corpses and dying men are stacked up together like cordwood and we have to wade through puddles of literal corpse juice?” Lawrence says “Yes,” so the doctor shouts at him and then hits him, which makes Lawrence start laughing at the bleak absurdity of the situation. At no point does it seem to be related to how Lawrence is dressed. The doctor thinks that Lawrence is responsible for how appalling the hospital is, when Lawrence is actually the guy trying to fix the situation.

“Other figures, such as British archaeologist and writer Gertrude Bell, were better known at the time …”

I hadn’t heard of her, thank you. And it turns out that four of her books are on Project Gutenberg.

https://gutenberg.org/ebooks/author/46514