Gazing at the Poe Girl

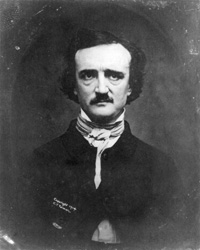

On his bicentennial, Edgar Allan Poe is being celebrated for many things: his grotesque horror, his flights of fancy, his progenitor detective, and his scientific authenticity. But what of his women: the lost Lenore, the chilled and killed Annabel Lee, the artless Eleonora? The Poe Girl, as I collectively refer to these and Poe’s other female characters, stems from an aesthetic belief recorded in his “Philosophy of Composition:” “ the death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.” But the Poe Girl is not only an invalid beauty cut down in her prime, but a specter that either haunts her lover out of revenge and anger or out of a desire to comfort. Whatever the various Poe Girls’ motives, they all share one common trait best expressed in “Eleonora”: “that, like the ephemeron, she had been made perfect in loveliness only to die.”

In poetry, the Poe Girl is but a memory, an absent presence. In his tales, the Poe Girl creates a more complex archetype. Some critics dismiss the Poe Girl as a mourning mechanism for the author’s wife; however, before Virginia Poe’s fatal hemorrhaging in January 1842, Poe had already published the stories I’ll discuss: “Berenice” (1835), “Morella” (1835), “Ligeia” (1838), and “Eleonora” (1841).

Immediately after his wife’s diagnosis, his pen took a turn with “The Oval Portrait,” published in April 1842, to focus on the fearful reality Poe was facing. After “The Oval Portrait,” Poe completely turned away from mourning his female characters to focusing on their violent murders in his detective tales. However, it will not be these victims, whose roles are minor within their stories, that we will look at but the eponymous heroines. Shortly after that, female characters all but dwindled in Poe’s tales, making an occasional appearance as a corpse in transport in “The Oblong Box,” and as a futuristic epistolary observer in “Mellonta Tauta.”

The Poe Girl has come to represent several things to different theorists. Within feminist circles she is symbolic of liberation or of oppression from the gaze. Within alchemy she is the philosopher’s stone; with less mysticism, she provides a basic argument for individualism and the soul’s existence. While Virginia seemed to be a bill of health during the peak of the Poe Girl writings, it isn’t entirely unreasonable to compare her with the Poe Girl, and a closer look at her life will conclude this series.

Tooth and Nail

Within feminism, the Poe Girl’s necrotic state is controversial. Death is viewed as “the most passive state occurring” which affects how women are viewed or not viewed. Women, as dead objects, are passive, lifeless bodies for the gaze to contemplate and the mind to idealize. It is easy to fetishize something that is no longer there; therefore, the heightened ideal for a woman to achieve is to die and become an object.

In “Berenice,” the narrator Egaeus suffers from monomania, a now archaic malady where the afflicted obsess over ideas. Riddled by his affliction, he is incapable of love and after rhapsodizing the brilliance and beauty of his wife, states that “During the brightest days of her unparalleled beauty, most surely I had never loved her. In the strange anomaly of my existence, feelings with me had never been of the heart, and my passions always were of the mind.”

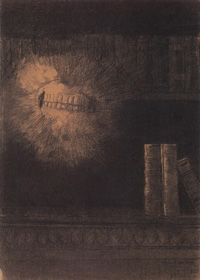

Berenice suffers from epilepsy, a disease characterized with life-threatening seizures and death-like trances. Unable to come to terms with Berenice’s person, Egaeus is horrified by her illness. His coping mechanism is to focus on her Platonian ideal: “The teeth!—the teeth!

everywhere, and visibly and palpably before me; long, narrow, and excessively white, with the pale lips writing about them

.” When Berenice is announced dead, Egaeus obsesses over the teeth until, driven insane, he violates her tomb and body to extract all her teeth.

Berenice suffers from epilepsy, a disease characterized with life-threatening seizures and death-like trances. Unable to come to terms with Berenice’s person, Egaeus is horrified by her illness. His coping mechanism is to focus on her Platonian ideal: “The teeth!—the teeth!

everywhere, and visibly and palpably before me; long, narrow, and excessively white, with the pale lips writing about them

.” When Berenice is announced dead, Egaeus obsesses over the teeth until, driven insane, he violates her tomb and body to extract all her teeth.

“The Oval Portrait” deals with objectivity in less visceral but more explicit terms. Published seven years after “Berenice” in 1842, Poe further explores woman as object by confining her entire person within the ultimate display case, a canvas. While exploring his new lodging, the narrator finds within his room the most life-like portrait he has ever seen. The lodging has a catalog of its paintings, and he finds a passage explaining the portrait’s circumstances: “ evil was the hour when she saw, and loved, and wedded the painter. He, passionate, studious, austere, and having already a bride in his Art: she a maiden of rarest beauty, loving and cherishing all things; hating only the Art which was her rival; dreading only the pallet and brushes which deprived her of the countenance of her lover.” Regardless, she poses for her husband, and confines herself in the studio until she becomes ill and literally dies of neglect:

for the painter had grown wild with the ardor of his work, and turned his eyes from the canvas rarely, even to regard the countenance of his wife. And he would not see that the tints which he spread upon the canvas were drawn from the cheeks of her who sat beside him. And when many weeks had passed, and but little remained to do, then the brush was given, and then the tint was placed; and for one moment, the painter stood entranced before the work which he had wrought; but in the next, while he yet gazed, he grew tremulous and very pallid, and aghast, and crying with a loud voice, ‘This is indeed Life itself!’ turned suddenly to regard his beloved:—She was dead!

Poe was not the first to write about dead women. There was the courtly love of Dante and Beatrice, and the love poems of Novalis and Mérimée, not to mention the general Romantic dwelling on premature death as metaphor for sublimity and the ephemeral. Therefore, Poe was working within a “Western tradition of masking the fear of death and dissolution through images of feminine beauty.”1

In her book, Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity and the Aesthetic, feminist scholar Elisabeth Bronfen looks at Western aesthetic death culture. She sees within Poe’s work the old trope that a woman’s beauty masks human vulnerability. Bronfen also sees in Poe’s women the muse-artist paradigm where “ death transforms the body of a woman into the source of poetic inspiration precisely because it creates and gives corporality to a loss or absence . The Poet must choose between a corporally present woman and the muse, a choice of the former precluding the later.”2 In “The Oval Portrait’s” case, “the woman, representative of natural materiality, simultaneously figures as an aesthetic risk, as a presence endangering the artwork, so that as the portrait’s double she must be removed.”3

Recently, Poe’s work has been given a more sympathetic look by feminists. While some, like Beth Ann Bassein, believes Poe was reinforcing oppressing images, others like J. Gerald Kennedy and Cynthia S. Jordan “argue that Poe did, indeed, know better, that he did not simply reinscribe conventional (repressive) attitudes toward women but that he critiqued these attitudes in his tales.”4 One of the stronger arguments is that most of Poe’s women refuse idealization and objectification by refusing to stay dead. Female characters like Ligeia and Morella are wise and powerful, the possessors of esoteric and arcane knowledge, and often described in intimidating terms: “ the learning of Ligeia: it was immense—such as I have never known in woman…but where breathes the man who has traversed, and successfully, all the wide areas of moral, physical, and mathematical science?” As with Ligeia, Morella’s husband is also in awe of her erudition: “ I abandoned myself implicitly to the guidance of my wife, and entered with an unflinching heart into the intricacies of her studies.” These are proactive women, and as we will see in the following sections, used their knowledge to rage against the night, as Dylan Thomas would say.

1 Kot, Paula. “Feminist ‘Re-Visioning’ of the Tales of Women.” A Companion to Poe Studies. Ed. Eric W. Carlson. Westport: Greenwood Press. 1996. p. 392.

2 Bronfen, Elisabeth. Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity and the Aesthetic. Manchester: Manchester University Press. 1996.p. 362.

3 Ibid., p. 112.

4 Kot, Paula. “Feminist ‘Re-Visioning’ of the Tales of Women.” A Companion to Poe Studies. Ed. Eric W. Carlson. Westport: Greenwood Press. 1996. p. 387-388.

S.J. Chambers has celebrated Edgar Allan Poe’s bicentennial in Strange Horizons, Fantasy, and The Baltimore Sun’s Read Street blog. Other work has appeared in Bookslut, Mungbeing, and Yankee Pot Roast. She is an articles editor for Strange Horizons and was assistant editor for the charity anthology Last Drink Bird Head.