A Prima Primer

The basis of alchemy was to transmute prima materia (lead), representing the material of creation, by placing it into a furnace until it changed through various phases to come out as the desired product: the philosopher’s stone. According to Randall A. Clack’s “Strange Alchemy of Brain: Poe and Alchemy,” a chapter in the wonderful Companion to Poe Studies, alchemy on a philosophical level represents “spiritual gold” that emerges “through the Alchemist’s creative imagination,” to emerge as new life.1

The prima materia transmutes in stages: nigredo, where black lead, the prima materia, is “tortured,” then purified, as represented by albedo, also known as the whitening. Once the transmutations are completed, the final stage, the rubedo, is signified by the glowing red heat seen from the still. At rubedo, a.k.a. the philosopher’s stone, “the prima materia has reached celestial or spiritual perfection [and at] this final stage represented the freeing of divine Wisdom imprisoned in the darkness of matter and delivering it to a new life.”2 The philosopher’s stone yielded a by-product, the elixir of life, that granted regenerative and healing powers, perhaps even immortality.

The Feminine Principle

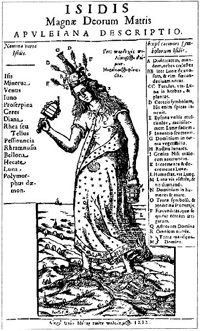

Alchemical mythology begins with the Hellenic Egyptian goddess Isis. While her son Horus battled rival gods abroad, Isis fled to Hermes where she was accosted by a lustful angel. Isis promised herself for the exchange of “life’s greatest secret.” The angel returns with a buddy, who Isis also charms, and he reveals to her “the great secret,” which is that everything stems from common matter and therefore can be transmuted. Isis is sworn to secrecy, her only allowance is to enlighten her son.3

Alchemical mythology begins with the Hellenic Egyptian goddess Isis. While her son Horus battled rival gods abroad, Isis fled to Hermes where she was accosted by a lustful angel. Isis promised herself for the exchange of “life’s greatest secret.” The angel returns with a buddy, who Isis also charms, and he reveals to her “the great secret,” which is that everything stems from common matter and therefore can be transmuted. Isis is sworn to secrecy, her only allowance is to enlighten her son.3

According to Jungian Marie von Franz, this myth is archetypal and demonstrates woman as the progenitor of all knowledge, but unlike Eve, whose knowledge acquirement brought sin upon man, Isis’s education:

is quite changed, for when Isis succeeds in getting the secret from those angels it is seen as a great achievement. So here we have a switch in the feeling judgment, though the event itself seems a very near parallel: the female element, the feminine principle, gets it from deeper layers and then is the mediator who hands it on to mankind.4

Isis’s departing of knowledge to Horus creates a relationship built upon “the great secret,” which leads to a required sympathy within Alchemy. Not only present is a feminine respect, but also a marriage of opposites: heaven is wedded to the earth, sun to moon, and body to spirit. It is this last marriage that Poe was most interested in.

Lifted Veils

“Ligeia” is not only distinguished by beauty but by brain, which is more vast and therefore perhaps threatening to the narrator husband, whose relationship is more pupil than lover:

the learning of Ligeia was immense—I said her knowledge was such as I have never known in woman—but where breathes the man who has traversed, and successfully, all the wide area of moral, physical, and mathematical science? With how vast a triumph—with how vivid a delight—with how much of all that is ethereal in hope did I feel, as she bent over me in studies but little sought—but less known,—that delicious vista by slow degrees expanding before me, down whose long, gorgeous, and all untrodden path, I might at length pass onward to the goal of a wisdom too divinely precious not to be forbidden!

Ligeia is dark, with fierce black eyes and long, ebon black hair, making her the prima materia that undergoes nigredo during her illness. Thrown into a furnace of disease, she is tortured and tormented by the dawning inevitability of her death:

Ligeia is dark, with fierce black eyes and long, ebon black hair, making her the prima materia that undergoes nigredo during her illness. Thrown into a furnace of disease, she is tortured and tormented by the dawning inevitability of her death:

Words are impotent to convey any just idea of the fierceness of resistance with which she wrestled with the Shadow. but in the intensity of her wild desire for life—for life . Yet not until the last instance, amid the most convulsive writhing of her fierce spirit, was shaken the external placidity of her demeanor. Her voice grew more gentle yet I would not wish to dwell upon the wild meaning of the quietly uttered words. to assumptions and aspirations which mortality had never before known.

Ligeia relates her death’s deconstruct through writing the poem “The Conqueror Worm.” According to Clack: “While the images of ‘The Conqueror Worm’ reflect the death (nigredo) of ‘Man’ alchemically, the poem seems to end too soon, for there is no alchemical resurrection (or transmutation).”5 This abrupt end upsets Ligeia who rages against the seeming irreversibility and totality of death. Shortly after this passionate rage, she dies. However, as the story progresses, she is resurrected as the philosopher’s stone.

After mourning Ligeia, the narrator marries Rowena, the fair and blue-eyed foil. The marriage was strained from the beginning: “I loathed her with a hatred belonging more to demon than to man. My memory flew back to Ligeia ”

By the second month, the newlywed Rowena falls ill and undergoes a similar nigredo as Ligeia. Feverish and bedridden, Rowena is hallucinatory and has nightmares of shadows outside her room. She oscillates between recovery and relapse, each cycle more violent and hallucinatory than before. Towards the end of Rowena’s convalescence, she tries to convince her husband that something lingers over her. The narrator begins to sense shadows but discredits it to his opium intake. However, when Rowena begins to fade, he rushes to restore her with a glass of wine:

…It was then that I became distinctly aware of a gentle foot-fall upon the carpet, and near the couch; and in a second thereafter, as Rowena was in the act of raising the wine to her lips, I saw, or may have dreamed that I saw, fall within the goblet, as if from some invisible spring in the atmosphere of the room, three or four large drops of a brilliant and ruby colored fluid. If this I saw—not so Rowena. She swallowed the wine unhesitatingly .

The fluid, Clack writes, is “analogous to the alchemical elixir vitae—the elixir of life that is a by-product of the philosopher’s stone.”6 After drinking the wine, Rowena relapses a final time and dies three nights later. Wrapped in burial bandages, the narrator keeps wake over her corpse throughout the fourth night to find that Rowena’s funereal looks are deceiving.

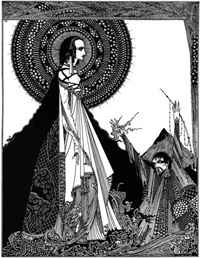

The narrator describes a series of reanimations: a sigh, a blush on the cheek, sanguine glow among the forehead (the rubedo). Unknowingly playing his role as partner, the sun to the moon, the narrator tries to revive Rowena, but as she did during her illness, she relapses back into death. This ebb and flow of life continues throughout the night, her corpse seemingly changed with each resurrection. He notices the corpse has grown longer, and when he goes to analyze her feet, the corpse recoils at his touch and jumps up, shaking off the bandages around its head:

there streamed forth into the rushing atmosphere of the chamber huge masses of long and disheveled hair; it was blacker than the raven wings of midnight! And now slowly opened the eyes of the figure which stood before me. ‘Here then, at least,’ I shrieked aloud, ‘can I never—can I never be mistaken—these are the full, and the black, and the wild eyes—of my lost love—of the Lady—of the LADY LIGEIA.’

The transmutation alluded to in “The Conqueror Worm” is now complete, as is Ligeia’s role as the philosopher’s stone. Also successfully completed is the alchemical marriage. While the marriage of Ligeia and the narrator was built on love and passion, there was also an implicit spiritual relationship that is realized by Ligeia’s reincarnation through Rowena: “The narrator metaphorically has attained the supernal, for Rowena has been alchemically transmuted into Ligeia—the narrator’s ‘lost love.’ Likewise, Poe has created the Philosopher’s Stone in the final image of Ligeia’s resurrection, for she represents a symbolic bridge to the unknown—the alchemical marriage of heaven and earth.”7

A similar knowledge is used for a similar gain in “Morella“; however, her preoccupation is not with a spiritual marriage, but with her own identity, as Part III will show.

1

Clack, Randall A. ” ‘Strange Alchemy of Brain’: Poe and Alchemy.” A Companion to Poe Studies. Ed. Eric W. Carlson. Westport: Greenwood Press. 1996. P. 369.

2

Ibid.

3

von Franz, Marie-Louise. Alchemy: An Introduction to the Symbolism and the Psychology. Toronto: Inner City Books. 1980. p.46.

4

Ibid., Pp. 46-51.

5

Clack, Randall A. ” ‘Strange Alchemy of Brain’: Poe and Alchemy.” A Companion to Poe Studies, Ed. Eric W. Carlson. Westport: Greenwood Press. 1996. P. 382.

6

Ibid., p. 383.

7

Ibid., p.384.

S.J. Chambers has celebrated Edgar Allan Poe’s bicentennial in Strange Horizons, Fantasy, and The Baltimore Sun‘s Read Street blog. Other work has appeared in Bookslut, Mungbeing, and Yankee Pot Roast. She is an articles editor for Strange Horizons and was assistant editor for the charity anthology Last Drink Bird Head.