Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

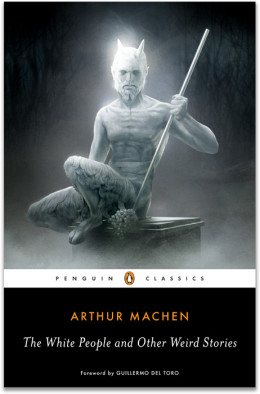

Today we’re looking at Arthur Machen’s “The White People,” first published in Horlick’s Magazine in 1904. Spoilers ahead.

“I must not write down the real names of the days and months which I found out a year ago, nor the way to make the Aklo letters, or the Chian language, or the great beautiful Circles, nor the Mao Games, nor the chief songs. I may write something about all these things but not the way to do them, for peculiar reasons. And I must not say who the Nymphs are, or the Dôls, or Jeelo, or what voolas mean. All these are most secret secrets, and I am glad when I remember what they are…”

Summary

A friend brings Cotgrave to a mouldering house in a northern London suburb, to meet the reclusive scholar Ambrose. Evidently Cotgrave’s a connoisseur of eccentricity, for he’s fascinated by Ambrose’s ideas about sin and sanctity. Good deeds do not a saint make, nor bad deeds a sinner. Sin and saintliness are both escapes from the mundane, infernal or supernal miracles, raptures of the soul that strives to surpass ordinary bounds. Most people are content with life as they find it—very few try to storm heaven or hell, that is, to penetrate other spheres in ways sanctioned or forbidden. Necessary as they are for social stability, laws and strictures have civilized us away from appreciation of the ideal natural who is the saint and the ideal unnatural who is the sinner. Still, if roses sang or stones put forth blossoms, the normal man would be overwhelmed with horror.

Cotgrave asks for an example of a human sinner. Ambrose produces a small green book. It’s one of his chief treasures, so Cotgrave must guard it carefully and return it as soon as he’s read it.

The Green Book turns out to be an adolescent girl’s account of strange experiences. It’s a book of secrets, one of many she’s written and hidden. She begins with words she must not define, the Aklo letters and Chian language; the Mao Games and Nymphs and Dols and voolas; the White and Green and Scarlet Ceremonies. When she was five, her nurse left her near a pond in the woods, where she watched a beautiful ivory-white lady and man play and dance. Nurse made her promise never to tell about seeing them. Nurse has told her a great many old tales, taught her songs and spells and other bits of magic that Nurse learned from her great-grandmother. These are all great secrets.

At thirteen, the girl takes a long walk alone, so memorable she later calls it “the White Day.” She discovers a brook that leads into a new country. She braves clawing thickets and circles of grey stones like grinning men and creeping animals. As she sits in their midst, the stones wheel and dance until she’s giddy. She travels on, drinking from a stream whose ripples kiss her like nymphs. She bathes her tired feet in a moss-encircled well. She passes through hills and hollows that from the right vantage point look like two reclining figures. Stumbling into one hollow reminds her of Nurse’s story about a girl who goes into a forbidden hollow, only to end up the bride of the “black man.” A final crawl through a narrow animal trail brings her to a clearing where she sees something so wonderful and strange she trembles and cries out as she runs away. Somehow she finds her way home.

For some time she ponders the “White Day.” Was it real or a dream? She recalls more of Nurse’s tales, one about a huntsman who chases a white stag into faery, where he weds its queen for one night; another about a secret hill where people reveled on certain nights; another about the Lady Avelin, white and tall with eyes that burned like rubies. Avelin made wax dolls to be her lovers or to destroy unwanted suitors. She called serpents to fashion for her a magical “glame stone.” She and her beloved doll were burned at last in the marketplace, and the doll screamed in the flames. And once Nurse showed the girl how to make a clay doll and how to worship it afterward.

At last the girl realizes that all Nurse taught her was “true and wonderful and splendid.” She makes her own clay idol and takes a second trip into the new country. Before entering the ultimate clearing, she blindfolds herself, so that she must grope for what she seeks. The third time around she finds the thing and wishes she didn’t have to wait so much longer before she can be happy forever.

Once, Nurse said she’d see the white lady of the pond again. That second trip, the girl does see her, evidently in her own reflection in the moss-encircled well.

The manuscript ends with the girl’s account of learning to call the “bright and dark nymphs.” The last sentence reads: “The dark nymph, Alanna, came, and she turned the pool of water into a pool of fire….”

Cotgrave returns the book to Ambrose. He has questions, but Ambrose is cryptic. Too bad Cotgrave hasn’t studied the beautiful symbolism of alchemy, which would explain much. Ambrose does tell him that the girl is dead, and that he was one of the people who found her in a clearing, self-poisoned “in time.” The other occupant of the clearing was a statue of Roman workmanship, shining white in spite of its antiquity. Ambrose and his companions hammered it to dust. Ah, the occult but unabated vigor of traditions. Ah, the strange and awful allure of the girl’s story, not her end, for Ambrose has always believed that wonder is of the soul.

What’s Cyclopean: “White People” aims for Epic Fantasy levels on the neologism production scale. On the vocabulary list: Dôls, Jeelo, voolas, voor, Xu, Aklo, and Deep Dendo. (If you speak too much Xu and Aklo, you will be in Deep Dendo.)

The Degenerate Dutch: In spite of the title, this story is less about race than about scary, scary women.

Mythos Making: Machen is one of Lovecraft’s four “modern masters” and a major influence on the Cthulhu Mythos. Many entities that you wouldn’t want to meet in a dark alley speak Aklo.

Libronomicon: Aside from the Green Book itself, our sub-narrator makes notable reference to (and somewhat imitates the style of) the Arabian Nights.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Subconscious note of “infernal miracles” may “lead to the lunatic asylum.”

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I can absolutely see why people love Machen. If I squint, I can even see why Lovecraft thought the man was a genius and this story a masterpiece. But on first encounter, I just want to slap him.

I want to slap him for so many reasons. Where to start? The trivial reason is aesthetics. The Arabian Nights style embedded stories are intriguingly inverted fairy tales that convey a really eerie mood—but alas, they’re embedded in framing conceits that go on, and on and on. The attempt at a girl’s voice simpers and giggles, and reads like someone telling you about their nonlinear dream at the breakfast table before coffee. The opening and closing bits are worse, more like being cornered by That Guy at a party. He tells you about his so-clever personal philosophy; you try desperately to catch the eyes of potential rescuers, but there you are with your diminishing plate of cheese saying “hmm” and “ummm” as his theological opinions get increasingly offensive.

The theology, oh yes. I’ve read enough Fred Clark to recognize arguments about salvation by works when I see them. This is a novel version—it’s an argument against works-based salvation via an argument against works-based sin—but I just have no patience. You know what? You treat people badly, you hurt people, then that makes you a bad person, whether or not you violate the laws of physics in the process. Lovecraft, on a good day, manages to persuade that violations of the natural order truly are intrinsically horrific. But he does it by getting away from standard Christian symbolism, and from pedestrian examples such as talking dogs.

Speaking of Christian symbolism, Machen’s forbidden cults are straight out of the Maleus Maleficarum. I’m not necessarily opposed to a good forbidden cult—but I’m not sure an author can use that tool without spilling out all their squicks and squids for the world to see. For Lovecraft, the cults are an outgrowth of the scariness that is foreign brown people, “nautical-looking negros” and New York immigrants and the great blurring mass of people who just don’t appreciate western civilization’s flickering light in the vast, uncaring darkness.

For Machen, as for the authors of the Maleus, what’s scary is women. Women with sexual agency especially. It’s front and center here: from the female sub-narrator with her coy references to forbidden pleasures, to the more overt stories about kissing fairy queens and clay lovers—and then killing your proper suitors—that underline the point. Women should follow the natural paths laid down for them by god, and marry when their fathers tell them. They shouldn’t listen to secrets told by other women, and they should definitely not find or make lovers who actually meet their needs. That way lies sin. Sin, I tell you, and death by random alchemical poisoning.

Women in this story are, along with children, “natural,” while men are blinded by “convention and civilization and education.” Thanks? I guess that’s supposed to make it worse when child-women violate the laws of nature. This story shows the hard limits of the Bechdel test, which it passes without blinking, and without gaining anything whatsoever from the experience.

And then we’re back to That Guy at the party (everyone else having discreetly made their exits), and men nodding sagely as they rationalize women’s mysteries and explain why they’re objectively horrifying. The ending feels very Podkaynish, the child’s whole life and death simply an interesting philosophical and moral lesson for men—the real, rational people—to discuss cleverly in a garden. Oh, how I wish Charlotte Perkins Gilman had lived to write fixit fic of this story.

Anne’s Commentary

Critical enthusiasm for “The White People” must have hit its zenith with E. F. Bleiler’s contention that it’s “probably the finest single supernatural story of the century, perhaps in the literature.” In Supernatural Horror in Literature, Lovecraft names Machen one of the “modern masters.” Today’s tale he calls a “curious and dimly disquieting chronicle” and a “triumph of skilful selectiveness and restraint [which] accumulates enormous power as it flows on in a stream of innocent childish prattle.” He also relishes the occult neologisms and the vividly weird details of the girl’s dream-not-dream journey.

“Dimly disquieting,” hmm. That was my first impression. I enjoyed the frame story opening as much as Cotgrave but frequently floundered while traversing the Green Book. It may be psychologically astute for Machen to couch the girl’s narrative in breathless long blocks of text, but really, paragraphs—specifically fairly frequent paragraph breaks—are among a reader’s best friends. The second read, like a second trip through difficult terrain, went much more smoothly. For one thing, I decided that the narrator’s name is Helen, based on the lullaby Nurse sings her: “Halsy cumsy Helen musty.” Names, for me, ground characters in fictive reality. For another, I began to appreciate Helen’s consciousness-stream; like the brook in the story, it leads into a strange new world, its current sometimes shallow and meandering, sometimes deep and profoundly tumultuous. It floats or sweeps us from Helen’s personal experiences into Nurse’s teachings and Nurse’s cautionary yet alluring folktales. I liked the interpolated stories the same way I like the copious footnotes in Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell (or in Lake Wobegon Days, for that matter.) They enrich the main story. They broaden the mysteries of the White People and White Lands beyond Helen’s own trickle into a river of tradition, both dark and bright like the nymphs that occupy it—or, as “processes,” unlock it?

Nurse is a fascinating character, a true sinner as Ambrose defines the term. She comes from a line of witches, a community of women passing down the old lore and its secrets. Her great-grandmother taught her, and she teaches little Helen, possibly with the sanction of Helen’s mother, whom Nurse summons when the infant speaks in the “Xu” language. Helen’s father, on the other hand, fences Helen in with lessons and disbelief. He’s the perfect representative for that civilized mundanity Ambrose deems the foe of sin and holiness, for he’s a lawyer who cares only for deeds and leases. Whereas wise and powerful women, or at least bold ones, dominate Nurse’s stories: the eventual bride of the Black Man who ventures into a forbidden hollow; the fairy queen; Lady Avelin of the wax images.

Yet men can join the more “natural” gender (per Ambrose) and revel in the Ceremonies. Both a white lady and a white man astonish little Helen by the forest pond. The land of hills and hollows resolve at a distance into two human figures, both Adam and Eve. This story is a psychosexual feast, with “mounds like big beehives, round and great and solemn,” with jutting stones like grinning men and creeping beasts, with serpents that swarm over Lady Avelin and leave her a magic stone with their own scaly texture. Ripples kiss; well water is warm, enveloping Helen’s feet like silk, or again, nymphish kisses. I’m thinking that it’s the magic of menarche that allows Helen to put aside doubt and accept Nurse’s teachings as true, after which she lies down flat in the grass and whispers to herself “delicious, terrible” things, she makes a clay doll of her own and returns up the narrow, dark path to the clearing of the white statue too beautiful and awful to glimpse a second time.

Lovecraft supposes this statue represents the Great God Pan, father of another Helen. Ambrose hints that on a subsequent visit to the clearing, the author of the Green Book poisons herself—saves herself—in time. Or does she? Is the infernal ecstasy she craves attainable only through death, the sole possible escape from all the living years she’ll otherwise endure before she can be happy forever and ever?

So, does Helen die a sinner or a saint, or a Saint or a Sinner? I wonder if we can really guess what Machen thought, or whether he could decide himself.

This may come as a shock, but next week marks our hundredth post! To mark this very special occasion, we’re watching something very special: Haiyoru! Nyaruani is (we assume) the only neo-Lovecraftian story ever to feature elder gods in their incarnations as anime schoolgirls. We’ll watch at least the ONA flash series (which runs about a half hour total), and possibly continue into Remember My Mister Lovecraft as whim and schedule permit.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

Didn’t T.E.D. Klein base one of his novels on The White People? or at least borrow from it.

Machen has his faults and not all of his work holds up but the narrative in the green book has glimpses of true weirdness.

Lovecraft on Machen: from “Supernatural Horror in Literature”:

“Of living creators of cosmic fear raised to its most artistic pitch, few if any can hope to equal the versatile Arthur Machen; author of some dozen tales long and short, in which the elements of hidden horror and brooding fright attain an almost incomparable substance and realistic acuteness. Mr. Machen, a general man of letters and master of an exquisitely lyrical and expressive prose style, has perhaps put more conscious effort into his picaresque Chronicle of Clemendy, his refreshing essays, his vivid autobiographical volumes, his fresh and spirited translations, and above all his memorable epic of the sensitive aesthetic mind, The Hill of Dreams, in which the youthful hero responds to the magic of that ancient Welsh environment which is the author’s own, and lives a dream-life in the Roman city of Isca Silurum, now shrunk to the relic-strown village of Caerleon-on-Usk. But the fact remains that his powerful horror-material of the ’nineties and earlier nineteen-hundreds stands alone in its class, and marks a distinct epoch in the history of this literary form.

Mr. Machen, with an impressionable Celtic heritage linked to keen youthful memories of the wild domed hills, archaic forests, and cryptical Roman ruins of the Gwent countryside, has developed an imaginative life of rare beauty, intensity, and historic background. He has absorbed the mediaeval mystery of dark woods and ancient customs, and is a champion of the Middle Ages in all things—including the Catholic faith. He has yielded, likewise, to the spell of the Britanno-Roman life which once surged over his native region; and finds strange magic in the fortified camps, tessellated pavements, fragments of statues, and kindred things which tell of the day when classicism reigned and Latin was the language of the country. A young American poet, Frank Belknap Long, Jun., has well summarised this dreamer’s rich endowments and wizardry of expression in the sonnet “On Reading Arthur Machen”:

“There is a glory in the autumn wood;

The ancient lanes of England wind and climb

Past wizard oaks and gorse and tangled thyme

To where a fort of mighty empire stood:

There is a glamour in the autumn sky;

The reddened clouds are writhing in the glow

Of some great fire, and there are glints below

Of tawny yellow where the embers die.

I wait, for he will show me, clear and cold,

High-rais’d in splendour, sharp against the North,

The Roman eagles, and thro’ mists of gold

The marching legions as they issue forth:

I wait, for I would share with him again

The ancient wisdom, and the ancient pain.”

… Less famous and less complex in plot than “The Great God Pan”, but definitely finer in atmosphere and general artistic value, is the curious and dimly disquieting chronicle called “The White People”, whose central portion purports to be the diary or notes of a little girl whose nurse has introduced her to some of the forbidden magic and soul-blasting traditions of the noxious witch-cult—the cult whose whispered lore was handed down long lines of peasantry throughout Western Europe, and whose members sometimes stole forth at night, one by one, to meet in black woods and lonely places for the revolting orgies of the Witches’ Sabbath. Mr. Machen’s narrative, a triumph of skilful selectiveness and restraint, accumulates enormous power as it flows on in a stream of innocent childish prattle; introducing allusions to strange “nymphs”, “Dôls”, “voolas”, “White, Green, and Scarlet Ceremonies”, “Aklo letters”, “Chian language”, “Mao games”, and the like. The rites learned by the nurse from her witch grandmother are taught to the child by the time she is three years old, and her artless accounts of the dangerous secret revelations possess a lurking terror generously mixed with pathos. Evil charms well known to anthropologists are described with juvenile naiveté, and finally there comes a winter afternoon journey into the old Welsh hills, performed under an imaginative spell which lends to the wild scenery an added weirdness, strangeness, and suggestion of grotesque sentience. The details of this journey are given with marvellous vividness, and form to the keen critic a masterpiece of fantastic writing, with almost unlimited power in the intimation of potent hideousness and cosmic aberration. At length the child—whose age is then thirteen—comes upon a cryptic and banefully beautiful thing in the midst of a dark and inaccessible wood. She flees in awe, but is permanently altered and repeatedly revisits the wood. In the end horror overtakes her in a manner deftly prefigured by an anecdote in the prologue, but she poisons herself in time. Like the mother of Helen Vaughan in The Great God Pan, she has seen that frightful deity. She is discovered dead in the dark wood beside the cryptic thing she found; and that thing—a whitely luminous statue of Roman workmanship about which dire mediaeval rumours had clustered—is affrightedly hammered into dust by the searchers.”

Open question: is there any evidence that Machen was ever aware of Lovecraft’s work?

Post 100: Congratulations! If you want me, I will be fleeing from the deadly light of Lovecraftian anime pixels into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

@1: Klein’s only published novel, The Ceremonies, makes reference to “The White People”.

@1,

Yep.Klein’s novel THE CEREMONIES was heavily influenced by “The White People.”

I was profoundly unimpressed with this one. Lovecraft may have found it wonderful, particularly praising the voice of the Green Book segment, but it left me cold. I found the connection between the framing bits and the GB to be too vague for my taste. And oh God the book. I’m with Anne on paragraphs. I kept having these Quentin Tarantino moments (“Paragraphs, melon farmer!) that made it really hard to enter the world of the story. Of the four stories in the collection our hosts linked to, I think this is the least of them.

If you go and put words in front of me, I will read them, so I wound up reading all four stories. In the first one, “A Fragment of Life”, there is a character (only very briefly on stage) who turned the money he made as a coal seller into real wealth by buying land in Crouch End. He then may (or maybe not, the witness winds up institutionalized) get involved with a number of very strange people. That bit had a little extra force after we read the Steven King story.

Anyway, I’d have to rate Machen as the least of HPL’s four modern masters. Like Ruthanna, I see what other see in him, but he’s no James, Dunsany, or Blackwood.

@2:Open question: is there any evidence that Machen was ever aware of Lovecraft’s work?

He was at least aware of SUPERNATURAL HORROR IN LITERATURE. Donald Wandrei sent him a copy, and he received a reply:

“I received a letter to-day from Machen, in which he mentioned your article and its hold on him”

Joshi, LOVECRAFT: A LIFE, 424

The stones sound like Carnac.

I read this for the first time a couple of months ago. Pretty good; it struck me as being really about ambiance rather than plot.

I like that was written away before the 1920

“Squicks and squids,” indeed. Lovecraft’s work was part squick and part squid, with the squid part much smaller than many people seem to think.

I shared your “Shoggoths in Bloom” post on Ana Mardoll’s blog and on my Facebook page, where it was much enjoyed. Thanks again.

Where to start? Agreed about the style of the Green Book–the girl was 16 but sounded younger, developmentally delayed or just unskilled I am not sure which–perhaps due to Machen’s not knowing how to sound like a teenager; someone needed to teach her how to do an outline first.

Agreed also about the disjunct tween the framing narratives and the story, though both get the mind going. That bit about the window falling/sympathetic infection is not only implausible but doesn’t fit in at all.

Why did the nurse vanish? If she had lived, would she have helped the girl find an alternative to suicide?

I am so sick of people who find nothing other than sexual stuff in Machen’s work; there seem to have been drugs involved in this one as well and music. Machen is not someone I would expect to be prudish, after all he translated the works of Casanova and also Le Moyen De Parvenir, which was nothing other than a string of 17th century dirty jokes. (Don’t bother, they weren’t that great.) So he could allude to it discreetly after the fashion of the time, but it seems to me that he had bigger things to be scared of, and these are the interesting ones. As a Left Hand Path mind, I am not sure I believe in sin to start with, though the universe-upsetting examples (singing flowers etc.) are scary, and I was never quite convinced that the mysteries found by the girl were inherently harmful; many dangerous things can be made useful with the proper care, as Ambrose himself admits–he does like to show off his knowledge without really showing us–and I was surprised and dismayed to find that she had either done a self-sacrifice like those cultists who tried to follow that comet, or else accidentally, cumulatively (“in time”) OD’d on something. And if the awful (which then meant awesome) lore continues unabated in places, how come there aren’t dead youngsters scattered all over the rural countryside? I think, though I am not sure, that his writing went into a bit of an eclipse about the same time that LSD and so on became big business, and people found their own way into ecstasy and sometimes horror.

All Machen’s stories have enough logic holes to use for a spaghetti strainer–if it isn’t amazing coincidences, it’s how the investigators wind up with so many key bits of evidence–but they have an oddly compelling quality for me even so. In this one, all the mysterious little allusions appeal–who wouldn’t be curious about the languages and the ceremonies? One person somewhere derived “glame stone” from “gleam”; as for the voor, which at first seems to mean ephemerality, it always made me think of those days when oddities of the cloud cover make morning look like afternoon or vice versa, or you’re at 47 degrees longitude and all the light comes from the north.

Thanks for a skilled dissection job, which I think you two could do for all Machen’s stories.

Ruthanna“Lovecraft, on a good day, manages to persuade that violations of the natural order truly are intrinsically horrific. But he does it by getting away from standard Christian symbolism, and from pedestrian examples such as talking dogs.”

Interestingly, HPL had similar reservations regarding Machen’s religious worldview:

People whose minds are-like Machen’s-steeped in the orthodox myths of religion, naturally find a poignant fascination in the conception of things which religion brands with outlawry and horror. Such people take the artificial and obsolete concept of “sin” seriously, and find it full of dark allurement. On the other hand, people like myself, with a realistic and scientific point of view, see no charm or mystery whatever in things banned by religious mythology. We recognise the primitiveness and meaninglessness of the religious attitude, and in consequence find no element of attractive defiance or significant escape in those things which happen to contravene it. The whole idea of “sin”, with its overtones of unholy fascination, is in 1932 simply a curiosity of intellectual history. The filth and perversion which to Machen’s obsoletely orthodox mind meant profound defiances of the universe’s foundations, mean to us only a rather prosaic and unfortunate species of organic maladjustment-no more frightful, and no more interesting, than a headache, a fit of colic, or an ulcer on the big toe. Now that the veil of mystery and the hokum of spiritual significance have been stripped away from such things, they are no longer adequate motivations for phantasy or fear-literature. We are obliged to hunt up other symbols of imaginative escape-hence the vogue of interplanetary, dimensional, and other themes whose element of remoteness and mystery has not yet been destroyed by advancing knowledge…..

SELECTED LETTERS, IV, 4

It seems that at least one of Lovecraft’s epistolary friends had trouble figuring out what was going on in “The White People”:

As for the essentials of the plot-you haven’t quite got ‘em yet, though you probably would have if I had sufficiently stressed the relationship between this tale & THE GREAT GOD PAN. This, then, is the dope: I. The image found in the woods was that of two entities locked in a monstrous & obscene embrace-from which, had they been living things, would have been born a Thing of non-human horror….like Helen Vaughan in THE GREAT GOD PAN, or the boy in THE BLACK SEAL.II. On account of a sympathetic action like that described in the prologue, the now-adolescent child-though without contact with any creative element-became pregnant with a Horror, to whose birth (knowing what she did of dark tradition) she could not look forward without a stark frenzy far beyond the fear of mere disgrace. Thus she killed herself. If she had not, a nameless hybrid abnormality of daemonic paternity would have been loosed upon the world. There seems to be very little question about the correctness of this interpretation, since several small allusions towards the end-especially regarding the girl’s age & and the nature of the image-join with earlier allusions to sketch the implications. Most analytical readers get this idea without much difficulty, & others see it unmistakably after being tipped off. This kind of plot was what the 1890’s regarded as the acme of horror-& it certainly does pack a pretty sombre shiver. But as I said before, that isn’t the real crux of the tale. The big thing is the tense, insidious atmosphere-landscape, half-hinted legendry, & all that.

SELECTED LETTERS, III, 348-49

” if roses sang … the normal man would be overwhelmed with horror.”

So, Machen would consider your average Merrie Melodies cartoon a glimpse of pandemonium? :)

Ambrose and Cotgrave, but most especially Ambrose, need to be thrown into the Black Pit, or bitten dead by the Black Snake in the pool, or imprisoned beneath the very biggest heaviest Voorish Dome in Deep Dendo, or… I don’t really care what, just as long as they’re never seen again. It seems a horrible smug frame round an eerie, fascinating picture. And I’m with Ruthanna on Ambrose’s theology: I wouldn’t let one of his “saints” get between me and the door.

Apart from the frame, WP seems far more morally ambiguous than Machen’s other eldritch-tales (at least the ones I’ve found online). “The Great God Pan”, “The White Powder”, “The Black Seal”, all make it thumpingly clear that the eldritch is Evil, corrupting of body, mind and spirit. Helen’s secret world just doesn’t fit into that black-and-white scheme: too much wonder and fascination and beauty alongside the sinister. Pickman would probably laugh and say that Machen scared himself with the story, and locked it in a box of Finest Morality to keep the dream-stuff from getting out.

*Googles some of the listed weird words* Interesting.

Hah. The only “Original Sins” I’m looking for were born in Garth Nix’s brain. Their story does involve a fish-worshipping cult and a Cthulhu lookalike, though. And some other eldritch abominations, and alternate dimensions. And the attempted destruction of the universe. Good times.

Machen’s view of religion, sin, and evil at this point are interesting in light of later developments. Around the turn of the century, his wife died and he briefly became involved with Aleister Crowley and the Golden Dawn. He soon chucked all that and spent the rest of his life interested in mystical Christianity through the lens of the Celtic Church and the Holy Grail. There’s probably enough there for a couple of doctoral theses.

I think it is probably the greatest supernatural horror story ever written, and I find the Green Book profoundly disturbing. Those who’ve been complaining here about the paragraphs may as well avoid Virginia Woolf’s masterpiece THE WAVES, which it prefigures stylistically and formally.

Since nobody else has mentioned it, the Green Book is actually a fragment of a novel Machen never finished. He saved it by framing it as “The White People”.

I’m just amused by Lovecraft’s use of the phrase, “This, then, is the dope.”

OneRatNoWalls put it better than I could, and I’ve long noted the callousness of Machen’s detectives/frame characters. They love to have fun visiting “Queer Street” but don’t have to face the burden of living there, and the people who do are just fodder for self-congratulation over one’s forensic cleverness, and sources of curious souvenirs. Here, where a mysterious rural otherworld is the setting instead of London slums, same thing.

Someone—big name comic artist/writer but I forgot–did a clever spin on the Aklo business in a story called “The Courtyard”, which appeared in one of the Starry Wisdom anthos and was later made into a comic. Who knows, maybe some conlangers are working on it too…

I did like the reference to infrasound in the prologue, something felt but not heard. It is something to be reckoned with, even if the “brown note” myth is exaggerated.

“Someone—big name comic artist/writer but I forgot–did a clever spin on the Aklo business in a story called “The Courtyard”, which appeared in one of the Starry Wisdom anthos and was later made into a comic…”

It’s by Alan Moore and is in the first Starry Wisdom book.

@18

As am I. Infinitely.

Anyone notice that the Horlick’s magazine was put out by the same people who made those malted milk tablets that I once liked but haven’t found in eons?

I have the Chaosium edition, with the absurd floating potato on the cover, and it contains “A Fragment of Life” too. This makes an interesting companion to “White People”. Everyone’s experienced the urge to chuck it all and head for the green spaces. The creepiest part, aside from the woman raving upstairs, is the fate of the aunt who was “put away”–mental institutions can’t have been fun places then (either).

I keep thinking that the statue/image in “White People” was some sort of intricate composite of many creatures, not all recognizable, intertwined in various ways, and wish they hadn’t destroyed it. I wonder also if the makers had used some slightly fluorescent paint to make it seem luminous, but then again, some types of stone are very white.

@18/21: Nothing odd at all in that. Lovecraft wasn’t above using modern vernacular in his letters, though usually couched with a bit of a nudge and a wink. Ironically, I suppose you might say. (Oh, God. Was Lovecraft a hipster?)

@23: Note the gnomic utterances of the enigmatic entity Oorn (though I don’t know whether Lovecraft or Barlow’s to blame for that one).

Angiportus @@@@@ 10: I interpret “in time” as “given enough time” – a cumulative overdose rather than suicide. But it could go either way. And yes, not only sex–but oy, the sex.

Trajan23 @@@@@ 11: In this, Lovecraft is absolutely spot-on. But his own work goes beyond what he describes here–if he’d just written “the devil in the gaps” (so to speak), that aspect of his work would have aged much more poorly as science advanced. Instead, the best stuff is about the danger of knowing more combined with the inability to avoid looking–a fear that 21st century types can still very much relate to.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 23: Well, he did know about Lovecraft before Lovecraft was cool.

Love the Machen or hate it (my, this does seem to be a polarizing story), I side-eye anyone who’s confident they know exactly what’s going on with the plot–our friend Howard very much included. I’m not convinced Machen knew what that statue looked like any more than Lovecraft knew the precise shade of the Color.

T.E.D. Klein on “The White People”:

The girl’s stream-of-consciousness style, at once hallucinatory and naïve, lends a spellbinding immediacy to the narrative, and for all its confusion and repetitiveness, it remains the purest and most powerful expression of what Jack Sullivan has called the “transcendental” or “visionary” supernatural tradition. Most other tales in that tradition, such as Algernon Blackwood’s “The Wendigo,” E.F. Benson’s “The Man Who Went Too Far,” and Machen’s own “The Great God Pan,” merely describe encounters with the dark primeval forces that reign beyond the edge of civilization; “The White People” seems an actual product of such an encounter, an authentic pagan artifact, as different from the rest as the art of Richard Dadd is different from the art of Richard Doyle.

Deepest apologies to all, but I think I wasn’t in the right mood when I picked up The White People. I came away with mental pictures of a very over the top girl who did things like tie a big, ladybug pattern bandana over her face while she stumbled around blind through a lot of close growing bushes (probably the kind with big thorns), no doubt running into a few trees, and maybe some poison ivy and a beehive, before finally bonking head first into a forgotten statue no one else cared much about. She decided (possibly due to head injuries) that this meant some kind of awesome enlightenment.

Oh, and her first “supernatural” event was when she saw a lady cavorting with a man. While she could not identify the woman, her nurse was absent during this and later told her she shouldn’t talk about what she’d seen.

And we’re seriously supposed to believe that witchcraft is the only explanation for this and for why the nurse might have been a bit prone to telling stories with sexual overtones.

Meanwhile, the guy telling this story later concludes that wandering through the woods with a bandana wrapped around your head is proof of some kind of spiritual evil. The story may have hinted that her death was a suicide, but (sorry) I think accidents are bound to happen if you insist on charging blind into stone statues.

Well, yes, Elynne, except she wasn’t blindfolded the first time she went there….I agree that the nurse had a boyfriend–and probably ran off with him or another one later, which might explain her disappearance. Thing is, though, when I bonk my head on something it just hurts, and has never resulted in any transcendental experiences. And if she had hit hard enough to injure her brain, there’d be some kind of mark that the adults at home would have noticed. It’s just a dashed weird story that doesn’t make much sense.

Interesting speculations on the statue: I always imagined it as just some sort of priapic faun or something similar, which is foul and wrong BECAUSE PAGANISM.

For me, it’s always been the trip rather than the destination: the description of the girl’s journey has always struck me as one of the most wonderfully spooky evocations of place and landscape, and enough to make one nervous about striking off on one’s one even through the most civilized of countryside.

Anyone wanna bet that falling-window-sash bit in the prologue was cribbed from “Tristram Shandy”? Only in that case it was something even more tender than fingers at stake…

A very late comment, here.

There is one angle of interpretation i hardly ever see mentioned. Is it possible that Cotgrave is misrepresenting the truth, that the girl’s feverishly ornate impressions are merely a fabulation to give covert expression to a far more human evil, in which Cotgrave himself is far more complicit & culpable than he’s willing to admit?

After all, there’s clear indication in the text that the man is something of a hypocrite; when he pours his guests a drink, he abuses “the teetotal sect with ferocity,” then proceeds to pour himself a glass of water.

I’ve always read the story as a dream of female (or childrens’) empowerment which in the end gets cruelly crushed by men imposing their world view. And that’s why it’s a horror story, not because paganism equals evil, or something like that.

Al @@@@@ 33: Good catch on the Malleus Maleficarum. I should have looked that up rather than relying on memory.

It seems like this reread may not have exactly what you’re looking for in a discussion of weird fiction, either in terms of style, length, or content. Fortunately there are many other venues out there.

Comments at 32 and 33 unpublished: Please continue to keep the tone of this discussion civil and see Tor.com’s moderation policy for our community guidelines.

I feel like I don’t really get this story, but I take it differently than most people?

The green book part wasn’t scary to me at all. The scary one was Ambrose. “I never saw the kind of lunatic before,” was the impression I had all the way through.

When I read the story, I got an impression that “poisoning” mentioned in the epilogue was a figure of speech, referring to the prologue, where Ambrose says a child might accidentally get a “key” to a hermetic “medicine cabinet” and “poison” themselves with the forbidden knowledge.

If HPL is right and the contact with the idol resulted in some diabolic Annunciation, then the girl could have died in childbith. Or even worse – the men who found her in the process of giving birth to a hybrid could have killed her or\and her offspring.

On the nature of the statue – again, if HPL was rigth, could it have been something like that? – http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/9926420/Erotic-Pompeii-goat-statue-arrives-in-the-British-Museum.html

Actually the epilogue and HPL’s explaination were a huge surprise to me – I was reading this story with more of a “Pan’s Labyrinth” feeling of protagonist’s innocense and magical adventure, and had no idea there was a sex\impregnation theme there, except for maybe some slightly lesbian nymph kisses. I guess you can see this story in two completely different ways. Try reading it to a child without prologue and epilogue – and ask them what they think happened and what the secret was.

There is a film “The New Daughter”, starring Ivana Bakero, the same girl who played in “Pan’s Labyrinth”. I don’t think “The New Daughter” is such a good movie, but it is the same story as “Pan’s Labyrinth” – a girl wanders off into the woods, finds the Fair People and decides to go stay with them and be their queen. Only in “Pan’s Labyrinth” we see all of it from the girl’s point of view, and it’s all wonderful and beautiful. In “The New Daughter” we see the same story from her father’s perspective, and it is all horrible, gross and overall Evil.

This story assumes that you’ll be very familiar with certain aspects of British cultural concern with the Roman Empire. A naive reader could very easily overlook that the strange ruins the girl stumbles into and wonders over were almost certainly the remains of a Roman fort – an educated Englishman would have known that, but we don’t necessarily. Machen also assumes that the reader will know what sort of statues, of which god, the Romans erected at crossroads. It seems Lovecraft didn’t – nor did he understand the reference to her “poisoning herself”, which is a clear reference to the earlier metaphor about a child playing with a medicine cabinet and misusing dangerous substances which are valuable when used appropriately.

The girl “Helen” didn’t literally poison herself, of course, although she did probably use certain powers injudiciously in a way which lead to her death. The story about the mother whose fingers withered when she saw a window fall on her child’s fingers is the core of the clue – it’s all about the law of sympathy – although all the other stories carry certain themes which constitute the rest of Machen’s hinting. When you know who and what the statue was of, the girl’s fate becomes horribly clear.