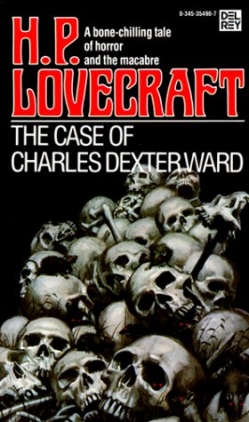

Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re looking at the first two parts of The Case of Charles Dexter Ward. CDW was written in 1927, published in abridged form in the May and July 1941 issues of Weird Tales; and published in full in the 1943 collection Beyond the Wall of Sleep. You can read the story here. Spoilers ahead.

Summary: In 1928, Charles Dexter Ward is confined to a private hospital near Providence, Rhode Island. He appears to have traded a twentieth-century mindset for an intimate acquaintance with eighteenth-century New England. Once proud of his antiquarian learning, he now tries to hide it and seeks knowledge of the present. Still odder are physiological changes: perturbed heartbeat and respiration, minimal digestion, and a general coarseness of cellular structure. He’s “exchanged” the birthmark on his hip for a mole on his chest, cannot speak above a whisper, and has the subtle “facial cast” of someone older than his 26 years.

Dr. Willett, Charles’s physician from birth, visits. Three hours later, attendants find Charles missing, without a clue to how he escaped. Nor can Willett explain. Not publicly, that is.

Charles was always prone to enthusiasms. His fascination with the past dated to childhood walks through the antique glamour of Providence. His genealogical researches revealed a hitherto unsuspected ancestor: Joseph Curwen, who’d come to Rhode Island from witch-haunted Salem, trailing dark rumors. Piqued by their relationship and an apparent conspiracy to destroy all records of Curwen, Charles sought information about the pariah. In 1919 he found certain papers behind paneling in Curwen’s former Providence home. Charles declared these papers would profoundly alter human thought, but Willett believes they drew young Charles to “black vistas whose end was deeper than the pit.”

Yet by the early 1760s, his strange ways led to social ostracism. The few savants to see his library came away vaguely appalled. One recalled seeing a heavily underlined passage from Borellus: “The essential Saltes of Animals may be so prepared and preserved, that an ingenious Man may…raise the fine Shape of an Animal out of its Ashes…and by the lyke Method, without any criminal Necromancy, call up the Shape of any dead Ancestour from [its] Dust.” Curwen kept his ship officers only through coercion, and hired “mongrel riff-raff” as sailors—sailors who often disappeared on errands to his farm. He bought many slaves for whom he couldn’t later account. He often prowled around graveyards.

To restore his position, and perhaps for more obscure reasons, Curwen decided to marry a woman beyond social reproach. He persuaded Captain Dutee Tillinghast to break his daughter Eliza’s engagement to Ezra Weeden. To the surprise of all, Curwen treated his bride with gracious consideration and relocated any untoward activities to his farm. Public outrage was appeased.

Not so the outrage of spurned Weeden. Weeden swore Curwen’s pleasure with newborn daughter Ann and his renewed civic contributions to Providence were a mask for nefarious deeds. He spied on Curwen and learned that boats often stole down the bay from his warehouses by night. Doings at the Pawtuxet farm were more disturbing. With confederate Eleazar Smith, he determined there must be catacombs under the farm, accessible through a hidden door in the river bank. The spies heard subterranean voices, as well as conversations inside the farmhouse: Curwen questioning informants in many languages. From accompanying protests and screams, he was no gentle interrogator. Bank slides near the farm revealed animal and human bones, and after heavy spring rains corpses floated down the Pawtuxet—including some that bridge loungers insisted weren’t quite dead.

In 1770, Weeden had enough evidence to involve some prominent townsmen, including Capt. Abraham Whipple. All remembered a recent incident in which British revenue collectors had turned back a shipment of Egyptian mummies, assumed to have been destined for Curwen. Then a huge naked man was found dead in Providence. His trail led back through the snow to Curwen’s farm. Old-timers claimed the corpse resembled blacksmith Daniel Green, long deceased. Investigators opened Green’s grave, and found it vacant. Intercepted letters suggested Curwen’s involvement in dark sorceries.

Curwen grew visibly anxious and intensified his Pawtuxet operations. The time had come to act against him. Captain Whipple led a force of a hundred men to the farm. None actively involved in the raid would speak of it afterwards, but reports from a neighboring family and a guard posted at the farm’s outskirts indicated a great battle took place underground. Charred bodies, neither human nor animal, were later found in the fields. Monstrous cries sounded above musket fire and terrified screams. A mighty voice thundered in the sky, declaiming a diabolical incantation.

Then it was Curwen who screamed, as if whatever he’d summoned hadn’t wished to aid him. He screamed, but he also laughed, as Captain Whipple would recall in drunken mutters: “T’was as though the damn’d ____ had some’at up his sleeve.”

The wizard’s body was sealed in a strangely-figured lead coffin found on the spot. Later Eliza’s father insisted that she and Ann change their names, and effaced the inscription on Curwen’s gravestone. Others would assist in obliterating Curwen from the public record. He should not only cease to be, but cease ever to have been.

What’s Cyclopean: Nothing here, but keep an eye out in later sections. For now we’re still at the gambrel stage. We do get a delightful adverb: “ululantly.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Curwen’s sailors are “mongrels,” and his farm is guarded by “a sullen pair of aged Narragansett Indians… the wife of a very repulsive cast of countenance, probably due to a mixture of negro blood.” And yet, this story is relatively sympathetic to other races. Not only is it portrayed as a bad thing to sacrifice imported African slaves to unholy powers (though not to enslave them in the first place), but in the next section we’ll actually get two named African American characters about whom nothing at all bad is implied. They own Curwen’s old house, and shared historical curiosity leads them to cooperate with Ward’s investigations. This is as good as Lovecraft gets on race, which is pretty sad.

Mythos Making: Various elder deities are discussed in quaint ‘Ye Olde Yogge Sothothe’ terms, along with mention of nameless rites in Kingsport. It’s likely that the Blacke Man spoken of in Curwen’s letters is, though normally in colonial New England a byname of more pedestrian devils, Nyarlathotep.

Libronomicon: Curwen’s library includes Hermes Trismegistus, the Turba Philosophorum, Geber’s Liber Investigationis, Artephius’ Key of Wisdom, Zohar, Albertus Magnus, Raymond Lully’s Ars Magna et Ultima, Roger Bacon’s Thesaurus Chemicus, Fludd’s Clavis Alchimiae, and Trithemius’ De Lapide Philosophico, and the infamously quoted Borellus. The Necronomicon makes its inevitable appearance, lightly disguised between brown paper covers as the “Qanoon-e-Islam.”

Madness Takes Its Toll: We start with a flashforward to Ward (or “Ward”) escaping from a private asylum. The whole thing is presented as a clinical psychology case with very singular characteristics—unique, with no similar cases reported anywhere.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Learning from Curwen’s example of failure to fake it, I’m going to come right out and admit that this is a first read for me. (While this whole series has been billed as a reread, in fact I’ve not been a completist in the past. And CDW is long and lacks aliens.) I’d been hoping to get through the whole thing before we posted Parts I and II, but toddlers. I’ve read summaries and am not worried about spoilers, but if there’s subtle foreshadowing I’ll leave its identification up to Anne.

Breaking with his usual methods, Lovecraft offers this tale from a third-person, semi-omniscient perspective. It works well, letting us jump from point of view to point of view and evidence scrap to evidence scrap without the usual artificialities. One wonders why he didn’t make use of this tool more often—perhaps it simply wasn’t as much fun. One can see hints of his usual style, in that specific sections are guided by not-quite-narrators: the first by Dr. Willett’s opinions of Ward’s case, the second by Ward’s own research on Curwen.

This is another story steeped in real locations. Indeed, we practically get a guided tour of Providence. Lovecraft does love his written-out maps! And hand-drawn ones too, of course. Anyone have insight into why he finds the precise geography of his street grids so important? One does note that the verbal map of Providence is considerably richer and more approving than that of the Lovecraft County towns.

This story also attempts, as in the later “Innsmouth,” to put together rumor and evidence into a damning picture. Here, though, there are enough reliable sources to actually succeed.

The “essential saltes of animals” quote makes me think inevitably of DNA. Of course, when this was written, we knew that some sort of hereditary essence existed, but not its nature. As it turns out, you sure can raise the shape of an animal at your pleasure, as long as you’ve figured out the secret to cloning (and haven’t taken “ashes” literally). Do let us know if you manage it.

Interesting to see how often H.P. revisits questions of identity, the self replaced by other selves, or sometimes by a new version of oneself that the old wouldn’t recognize. Intruding Yith, intruding dirty old men, intruding Deep One ancestry… now intruding ancestors that really should have stayed dead. In the grand and dreadful sweep of the cosmos, selfhood is a fragile thing. The obsession with madness is of a piece, another way that the self can be lost.

Speaking of repeated themes, here’s another story where marriage is a nasty thing, a route to intimacy with dark powers—poor Eliza Tillinghast. Though she gets a name—indeed, gets her own name back and gets out of the marriage alive, which is pretty remarkable for a female character in Lovecraft.

By the by, psychologists have recently run an experiment which is about as close as we can easily come to Lovecraftian possession or replacement—a “cyranoid” speaks words and intonation as directed by someone else over a discreet earpiece, and interacts with people who aren’t aware of this. No one notices, even when it’s a child speaking through a college professor or vice versa. Good news for anyone hoping to replace their relatives unnoticed in real life!

Anne’s Commentary

This novel is near my heart for two reasons: It’s steeped in the antique glamor of Providence, and it’s the primary inspiration for my own Mythos work. Early on, I planned for my hero to be another of Curwen’s descendants. That’s changed, but Curwen’s Pawtuxet legacy will certainly figure in the series. Who could resist ready-made underground catacombs full of unhallowed secrets?

Not me. Nope. Not even.

Living around Providence, I’ve often emulated Charles’s walks along the precipitous streets of College Hill. In Lovecraft’s time, Benefit Street had declined, leaving the Colonial and Victorian houses sadly neglected. Gentrification and a vigorous Preservation Society have reversed the decay, and the street now deserves its appellation of a “mile of history.” The infamous “Shunned House” is there, and many buildings by which Curwen must have strolled during his long tenure in the growing town. And the view from Prospect Terrace that entranced the infant Charles? It remains a thrilling smorgasbord for the antiquarian, and on an autumn evening, sunset does indeed gild spires and skyscrapers, while the westward hills shade into a mystic violet.

I currently live nearer the novel’s other locus, Pawtuxet Village. Its historical claim to fame is the June 9, 1772 attack led by none other than privateer Abraham Whipple. The Gaspee, a British customs schooner, went aground near the Village. Whipple and other Sons of Liberty boarded her, overcame the crew, then burned the ship to the waterline. Every June, we fete this blow to tyranny with parades, re-enactments and Colonial encampments. I’ve long wanted to question the gentleman impersonating Whipple over lubricating flagons of ale—c’mon, what really went down during that nasty business with Curwen? From a cosmic point of view, ridding Providence of necromancy was the Captain’s greater feat!

On the other hand, if the actor stayed in character, he might crown me with his flagon and follow it with scalding epithets. Better not to chance it.

I also rather like that Curwen’s daughter is named Ann. As Ruthanna noted, her mother Eliza came out of her brush with Mythos matters remarkably unscathed for a Lovecraft character of either gender. A different writer might have reunited her with Ezra Weeden. Huh. That could be the plot bunny of the week, but isn’t necessarily a fate to wish on Mistress Tillinghast given Weeden’s probable state of mind following his “revenge.”

The omniscient point of view resembles “The Terrible Old Man” in its cool distance and in the lack of purple prose that seems a natural (and welcome) outgrowth of stepping away from the action. Here, however, the key note is sincerity rather than irony. The terrors that beset Providence are not to be taken lightly. This is alternate history, properly buttressed with historical detail and personages—just think what might have happened if Curwen hadn’t been stopped!

Actually, I enjoy thinking about it. For me, Curwen is one of Lovecraft’s most intriguing characters, suave enough to please his ill-won bride, yet steeped in murderous monomania. Parts I and II leave us uncertain of his ultimate goals. From the start, he’s achieved unnaturally extended youth, though not absolute immortality. When exactly he makes a breakthrough in his wizardry, one must read closely to deduce. We’re told he’s always kept his associates in line through mortgages, promissory notes or blackmail. He shifts method five years before his death, in 1766. Thereafter, he wields damaging information he could only have pried from the mouths of the long-dead. Telling, too, is the change in midnight cargo transported to his farm. Before 1766, it’s mostly slaves for whom no later bills of sale can account. After 1766, it’s mostly boxes ominously coffin-like. Conversations overheard on the Curwen farm shift from mere mumblings and incantations and screams to those terribly specific catechisms in many languages. The confiscated Orne letter congratulates Curwen for continuing to get at “Olde Matters in [his] Way.” Apparently this late progress involves shafts of light shooting from a cryptic stone building on the farm.

Shafts of light. Hints from the Orne letter that Curwen better not summon anything “Greater” than himself. Hints from accounts of the Pawtuxet raid that maybe Curwen did summon “Greater.” What has he been up to? What would he have been up to if not for those Providence busybodies?

Here at the end of Part II, Lovecraft has me eager to learn the answers. Get to work digging them up, Charles!

We continue our Halloween season read of Charles Dexter Ward next week with Part III, “A Search and an Evocation.”

Photo credit: Anne M. Pillsworth

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She has a slightly dusty collection of brains in a closet somewhere.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.

Alienists! I do love the description of Providence here (at times I wonder if Lovecraft missed his true calling as a Rhode Island tour guide): one bit

“Here ran innumerable little lanes with leaning, huddled houses of immense antiquity; and fascinated though he was, it was long before he dared to thread their archaic verticality for fear they would turn out a dream or a gateway to unknown terrors.”

made me think of “The Music of Erich Zann”. I also appreciated the wealth of historical detail: knowing that there really was an Abraham Whipple and a “Gaspee Affair” somehow increases the verisimilitude of the more outlandish elements.

The first of a two part serial of The Case of Charles Dexter Ward was published in the May 1941 Weird Tales. Of potential interest in that issue were Robert Bloch’s “Beauty’s Beast” and August Derleth’s “Alitimer’s Amulet”; there were also a couple of Lovecraftian letters in the back.

ETA: Kurt Vonnegut used to advise writers to start as close to the end as possible. Here, Lovecraft again starts some time after the end…

I read TCOCDW twice, once when I was maybe 15 and first into Lovecraft. I then re-read it with the marvelous edition from The University of Tampa Press. Really, this should be the edition that everyone gets. It has notes and annotations by ST Joshi, and uses the corrected text. It also has numerous photos of sites in the text by Donovan K. Loucks, Lovecraftian geographer extraordinaire. The paperback is quiite affordable:

http://www.ut.edu/TampaPress/pressDetail.aspx?id=18777&terms=

My problem is, well, I just don’t like it. The whole first part with its Providence history/geography word salad is dull. I don’t think the author regarded it highly, and I don’t believe it was published in his lifetime. I view it more as his getting his experience with geography influencing the story and expressing his love for Providence. I like the plot but I found the text almost impenetrable.

I actually prefer the comic book edition from INJ Culbard and Selfmadehero because we basically just get the gist of the story, even if the art is not the best you ever saw.

My favorite way to enjoy the plot, which is very good, is the Dark Adventures Radio Theatre production from the HP Lovecraft Historical Society. It is superb. http://www.cthulhulives.org/store/storeDetailPages/dart-cdw-cd.html

The HP Lovecraft Literary Podcast did a 5 part series on CDW in 2010. Here is part 1: http://hppodcraft.com/2010/09/08/episode-54-the-case-of-charles-dexter-ward-part-1/

I’ve read it before, and it isn’t one of my favorites, by any means. HPL himself didn’t really care for it. I’ve been trying all week to read what gets covered today and only just managed to skim the first two chapters last night.

Once again, Lovecraft goes to great lengths to make us feel like this is the real world. He describes the Providence he knew in great detail and all of Curwen’s books that are cited are well-known alchemical texts. Well, except for the Necronomicon, of course, but the book it’s pretending to be is real (though not alchemical).

What stood out to me this time is the description of CDW before his discovery of the Curwen papers. It’s incredibly autobiographical. Apart from the hair color and his place of residence, Lovecraft has largely described himself.

I mentioned the to the authors, but it was too late to get this into the post. On Kickstarter currently, the first authorized H.P. Lovecraft video game is nearing the end of its run, and just happens to be “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward”. If you are interested in playing this story, seriously consider backing them! We only have until Halloween before this opportunity ends.

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/agustincordes/h-p-lovecrafts-the-case-of-charles-dexter-ward

And in the semi-regular list of “bits of HPL mythos that Charlie Stross borrowed for the Laundry” this week we have Ms Tillinghast, who’s name is used for a device (the Tillinghast resonator).

I didn’t spot any others though.

The quote at the beginning sounds like Jurassic Park.

It is ridiculous to call a colonial American town prehistoric. Stonehenge is prehistoric (and fits cyclopean architecture), but something that is just a few centuries old is not prehistoric. The desciption of the town is boring and too long anyway. Did he get paid by number of words?

Have any re-readers ever visited Providence? I have to wonder what it’s like and whether there’s still a place for a town where all of the roofs are gambrelled and all of the dead unquiet…

Those who are are not particularly enjoying this story may prefer Bear & Monette’s “The Wreck of the Charles Dexter Ward”. If you’ve read “Boojum” or “Mongoose”, you should know what you’re getting into.

I am very fond of Roger Corman’s cycle of movies based on Poe stories, and in 1963 he made a film in a similar vein based on The Case of Charles Dexter Ward. The Haunted Palace stars Vincent Price as Ward. Debra Paget and Lon Chaney, Jr. are co-stars and Charles Beaumont wrote the screenplay. I find the film to be particularly enjoyable (and if you enjoy Corman’s Poe cycle, or the Gothic horrors of Hammer studios films, you might too), and although it isn’t a note-for-note adaptation, it contains a lot of Lovecraft’s elements to the point you can tell it is based on the Lovecraft novel, even if you missed that part of the credits.

As far as the novel itself goes, I’ve almost finished it, and this is probably my third or fourth re-read in my lifetime thus far. I’m getting more out it now more that I ever did before. I’m finding an interesting inversion in myself as I follow this re-read; when I was in my teens and 20s, I loved Lovecraft’s more florid and purple stories much more than I did more straightforward tales such as this one and “The Call of Cthulhu.” Now that I’m in my 40s, that’s been flip-flopped to the point where I enjoy his straightforward narratives much more and find his purple passages to be sometimes annoying and intrusive. In this novel, the great wealth of ‘mundane’ detail that others are bored by, I am enjoying as much as the otherworldly elements.

I want to mention Shatterbrian AKA The Resurrected, a very good (and genuninely scary) adaptation of this story.

National Review Online has a podcast called ‘Between the Covers’ and the latest episode is about Lovecraft. They interview Leslie Klinger, the editor of The New Annotated H.P. Lovecraft and he says the CDW is his favorite story. It’s a good listen.

There looks to be a typographical error in this section; both my printed copy and Cthulhu Chick’s epub contain this sentence:

I suppose the word “snow” is supposed to be “scow”? Does anyone have a copy which reads differently?

Yep, it says “scow” in my copy of At the Mountains of Madness and Other Novels (the Joshi-edited Arkham House edition from the 1980s with the blue dust jacket).

I think CDW is the longest piece of fiction Lovecraft ever wrote? Like JohnBem above, I’ve found this story to grow on me over the years.

@7 – I was fortunate enough to visit providence for NecronomiCon in 2013. I walked through the neighborhood myslef. had lunch with Wilum Pugmire in the St. John’s Burying Ground while reading his sonnet about Poe, and then had awalking tour ith Darrell Schweitzer, while chatting with Cody Goodfellow. I’d say yes, the nieghborhood described in TCOCDW is still quite magical. Check out the University of Tampa Press edition. Visit the website of Mr. Loucks: http://www.hplovecraft.com. He provides a map for a walking tour.

Or better yet, there is a second NecronomiCon planned for summer of 2015, in August. Why not attend and hear your favorite authors read their own work, listen to scholarly papers, game with the creators of Call of Cthulhu and generally have a grand old time. They will certainly have more guided walking tours of Providence.

Not much to say this week, since I havven’t read CDW and have been busy looking for Deep-One-related books and sulking because none of my three libraries have The Innsmouth Cycle. (I read the original TSOI two years ago and hadn’t known until now that it captured the imaginations of so many writers, given how little love other aquatic humanoids and ocean-worshippers seem to get). But I always appreciate learning more about unfamiliar Lovecraft works in this blog’s interesting manner.

The Case of Charles Dexter Ward was the first Lovecraft story I read, in an

anthology in the early 1950s. I was fascinated by it. I found it hard to

follow the intricacies of the plot, but the wizards’ correspondence in archaic

English, and the antiquarian atmosphere, seemed persuasively authentic. I was

left with the impression that Salem witchcraft might have been like this, if

it had been real and actually worked.

@13 & 14: Might be the other way round, actually. A “snow” is an archaic term for a two-masted ship with square sails and a small trysail mast. Lovecraft’s handwriting is not readily apparent and the word was changed to snow after the 80’s Arkham editions. On the other hand, which word it should be remains a source of contention as neither ship quite seems to fit:

https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/alt.horror.cthulhu/G4siX1beCCM

This is why we need a variorum!

@15: It sounds like a great experience, though I’m sure I won’t be able to get there for it. Being sort-of familiar with the setting of the early stories of Ramsey Campbell doesn’t quite carry the same weight…

@17: I liked having the “authentic” forbidden lore mixed in with the likes of the Necronomicon. Here’s what I think Curwen was reading.

Hermes Trismegistus: the comparatively well-known alleged author of the Hermetic Corpus.

Turba Philosophorum: a 10th century book on alchemy, translated from Arabic.

Liber Investigationis: apparently a translation of Jabir ibn Hayyan’s Summit of Perfection.

Key of Wisdom: a translation of the mysterious Artephius’s most famous work.

Zohar: a foundational text of the Kabbalah.

Albertus Magnus: a very important medieval theologian who wrote about, among many other things, the work of Aristotle.

Ars Magna et Ultima: Lully’s reference work on Christianity, intended to win conversions through debate through a system of charts and diagrams inspired by the Islamic zairja.

Thesaurus Chemicus: the experimentalist monk Roger Bacon on the subject of alchemy.

Clavis Alchimiae: a work by the infamous adversary of Kepler, Robert Fludd.

De Lapide Philosophico: Does Lovecraft get confused here? There was an active Renaissance occultist and cryptographer by the name of Trithemius but the book he names is referenced elsewhere as being by the later Johannes Isaac Hollandus.

Borellus: Pierre Borel, 17th century physician and reputed alchemist.

I recently read James Blish’s The Devil’s Day, which endeavors to accurately represent medieval magic. This may also be of some interest.

Not much to add this week.

CDW is pretty straightforward bodyswitching/hostile takeover horror. As such it might not be HPL’s most famous but maybe his most “mainstream” story.

“WTH, HPL, you sold out!”

@6 birgit

re: ‘prehistoric’

Yep, as the word itself implies, anything prehistoric actually predates recorded history. As in “predates writing systems with which to write down stuff that has happened”.

So, yeah…even in a best case scenario HPL is at least several millennia late to the prehistoric party. I doubt there’s any snacks or drinks left…

@18 — Fascinating! Conveniently, I will have just such a varorium edition at some point in the unspecified (but hopefully not too distant) future …

@20: I hope that such a volume will clear up this and any further abstruse points of Lovecraftian orthography. Having checked my editions, it appears that The Case of Charles Dexter Ward is indeed the longest work by Lovecraft alone.

JohnBem @@@@@ 8: I agree about the “mundane” passages — the wealth of local and historical detail — in this story. For me, as in all works firmly grounded in the real (Salem’s Lot comes to mind), the horror is intensified thereby.

One problem with the “reality” which I’ve just noticed, as a long-time resident in Providence and Pawtuxet — building extensive catacombs in an often-flooded river valley seems a task beyond Curwen’s physical resources. Lovecraft does note the problem of bank erosion, which uncovers the bones of some Curwen victims. But where did Curwen’s workers put all the earth excavated from the tunnels? Towering piles of dirt and rocks aren’t easy to hide or transport unseen.

Oh well, maybe magic, or night gaunts bearing buckets off to that chasm in the Dreamlands where ghouls throw their bones. In which case they might as well have carried off the tell-tale bank-bones as well.

Maybe that wasn’t in their contract….

@21: I’m certain it will either clear them up or exacerbate them; whichever.

@21 SchuylerH

Is it really longer than Kadath? That seems longer to me.

@22 Anne

The dirt could have been dumped load by load into the river to be carried off downstream. As long as he didn’t dump too much at once, it ought to be carried off. (I have no idea how strong the Pawtuxet actually is/was, but if it was undermining the banks it ought to be possible.) Stones could have gone into construction or field walls or been used as ballast in Curwen’s ships.

@24: In my Gollancz Necronomicon, The Case of Charles Dexter Ward is found on pages 648 through 749. At the Mountains of Madness is 422 through 503 and The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath is 750-828.

Of course, without modern pumping systems, it’s likely that most of that extensive riverside tunnel system would’ve flooded & collapsed inside of a week, but I’m willing to overlook that for the sake of the story.

Yep, as the word itself implies, anything prehistoric actually predates recorded history. As in “predates writing systems with which to write down stuff that has happened”. So, yeah…even in a best case scenario HPL is at least several millennia late to the prehistoric party.

Not millennia… if we’re talking about North America, everything pre Columbus is prehistoric because they didn’t have writing systems. Similarly Australia for everything pre-Cook. But, yes, it is silly to talk about a colonial town as being prehistoric!

@27 a1ay

You’re forgetting to take into account, among other things, the K’n-Yan in the Americas and the Old Ones in Australia.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 24 & hoopmanjh @@@@@ 26 The Pawtuxet is a fairly shallow, narrow and slow river except in flood, so I think dumping much dirt into it would eventually dam the current at the dump site. In flood, especially in the spring, the river does get up the depth and strength to wash out banks, though, as HPL has it in the novel. In recent years it has flooded out many homeowners, so yeah, I think massive pumps would be necessary to keep those precious tomes and Saltes above water!

Then there’s the matter of all the dressed stone one would have needed to construct catacombs of such extent, not to mention carpenters to make six paneled doors for “innumberable” doorways!

So, alas, they still seem improbable in real life, but remain fun in story.

a1ay @@@@@ 27 and DemetriosX @@@@@ 28: If you’re talking about the US and Canada, yes, pre-Columbus we have to depend on the writing of Lovecraft’s various and sundry ancient races. If all you want is North America, various Mesoamerican cultures started writing considerably earlier. We have more writing in Aztec than in Ancient Greek–just less translated.

Checking my much-beloved copy of Charles Mann’s 1491 gives the earliest definitive date for Olmec writing as 300 BCE, with several indications that it may have started considerably earlier, and a quick Google suggests that we’ve since pushed this back to 900 BCE.

Many examples of North American writing were destroyed as blasphemous by the Spanish–look up the Inca’s knotwork khipu sometime. May they be preserved in the Archives.

@27 a1ay

You’re of course correct that North American Natives (excluding Mesoamerica) didn’t have a writing system pre-Columbus. I was looking at it from HPL’s Anglo-Saxon perspective, because he referred to a gambrel-roofed house as ‘prehistoric’. English and its roots have been around in written form for a very long time…

I’m just so glad I wasn’t the only one outraged that Eliza and Ezra were never reunited! What was the point of all the painstaking revenge?!

(I love these articles by the way!)