Remember back in the ‘60s when you’d buy a sci-fi paperback and there’d be two books packaged in one, with covers on each side, and when you finished one you’d flip the book over and read the other one? Signs is like that. (Except without the cover-flippy thing…) It’s two different movies—and I’m gonna talk about both of them.

Signs is GREAT Horror movie. From the moment the credits start, we’re trapped in a world full of doom and unease, with uncanny sounds playing over baby monitors, unnatural silences falling over endless fields of corn, and a terrible sense of dread underlying everything. The ambiance is unmatched.

Signs is a DEEPLY TROUBLING movie about religion. Like a lot of M. Night Shyamalan’s earlier work, Signs presents itself as one type of movie before turning into another. You thought you were in an alien invasion story—and you were! But surprise: it’s also about religious faith, in a very weird way.

Let’s start with the horror.

Also, let me say upfront that every performance in this movie is miraculous. And the first ten minutes of the film are, frankly, perfect. James Newton Howard’s score is incredibly tense, sets the tone through the credits, and then cuts off abruptly into utter silence as the first scene starts. In a few seconds, the camera looks through a thick, ripply window to show us a lush cornfield and an empty, silent playset, before moving back into the room and settling on a photo of a man, a woman, and two children, all smiling. The man from the photo startles awake and sits up into frame, gasping for air. We see that he’s sleeping alone on one side of his large bed, we see how haggard he looks, and we see the empty cross-shaped spot on his wall after he’s gotten up.

The movie has given us: lost wife, silent house, troubled sleep, lost faith. And where are those two kids?

This is all before we hear the high-pitched, terrified child’s scream that kicks the plot into motion—we already have a sense of the sadness and emotional stakes that will underpin everything that comes next.

The person screaming is the man’s daughter, and she’s screaming because she and her older brother have just found a crop circle in their corn. And from the moment the camera falls back to show us the pattern and just how tiny the humans are in it, the tension only gets worse.

Signs stays on the ground with the characters. We’re not in the Oval Office, or the Pentagon, or the Eiffel Tower or Red Square. We’re at a family farm in rural Pennsylvania. The man is Reverend Hess, a former Episcopal priest, who has focused on his farm since he lost his wife and his religious faith in the same night. His younger brother Merrill has moved in to help with the kids, Morgan and Bo, who are both very smart and really sweet. Morgan has asthma, and he seems to need his inhaler pretty often, and Bo leaves half-drunk glasses of water all over the house because she’s convinced the water is “contaminated”. The movie doesn’t reveal some E.T. or Mac & Me type connection with the aliens. Morgan buys a book about aliens that is, like all books about aliens, highly subjective, and he refers to Bo having “feelings”—intuitions about the future—but we never know how much credence to give them, and it’s never clear whether the adults even notice them. These are two normal, if shell-shocked, little kids.

All of the big “the aliens have landed” scare moments are folded into daily life: Bo and Morgan find the crop circle while they’re playing; Bo wakes her father up to tell him “There’s a monster outside my window”, but in the same breath asks for another glass of water, and it’s only several minutes later that Graham looks up and sees an alien on the roof (even then, he thinks it’s a local boy playing a prank); the family only learns about the size of the invasion when Bo complains that all the TV channels are playing the same show, and it’s news footage of crop circles around the world. The stuff that would be the “action” of most alien invasion movies plays out on the Hess’ TV, as the family either crowds around to watch, or resolutely ignores it.

The dread is relentless. No one has a plan, and this man and his grieving family are on their own. If a TV or radio is on, someone’s talking about aliens. Every time Graham Hess tries to interact with people, they call him “Father” and pour salt in the wound where his faith used to be. When he tries to take the family into town for a break, Morgan and Bo use their allowance to buy a book about aliens, the town’s Army recruiter harangues Merrill with theories about an alien recon mission, a pharmacy cashier blurts out a confession to Graham because she thinks the world is ending, and then the whole family sits down for pizza only to look up and see Ray Reddy, the man who accidentally killed Colleen Hess.

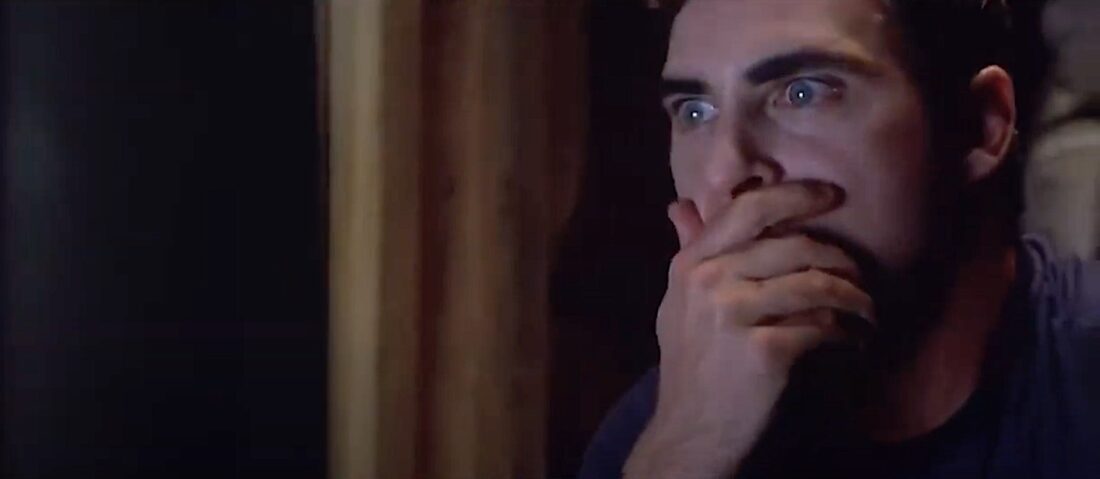

Back at the farm, the corn is always rustling in the wind—or is it aliens creeping ever closer to the house? For most of the film, the aliens are sounds we can barely hear, clicking noises over a baby monitor, scuttling on the roof, eerie silence on a summer night. We, the audience, only know as much as these characters—rumors, hearsay, news reports—and we’re subject to the same jolts of panic, culminating in what I (and others) would argue is one of the most frightening scenes put on film:

This is an alien scout, filmed by a terrified parent with a camcorder. There’s no reassuring talking head, no solid, square-jawed white dude in charge like in ‘50s sci-fi. We’re with Merrill in that scene, and his reaction is ours.

There’s not a single thing that parent with the camcorder can tell those screaming children.

There’s not a single thing Graham or Merrill can do to comfort Morgan and Bo.

Again, up to this point, a note-perfect horror movie. And then it starts to tip over into something else. When it becomes clear that the aliens are invading, there’s no sign that anyone is doing anything about it. The only military presence we see is the man at the Army Recruiting Office. There is no statement from a president, king, or pope. There is no sense that the US or Russia are planning to nuke the ships. Even though the aliens are clearly congregating near the crop circles, no official shows up at the Hess farm to ask any questions or offer protection.

This dovetails with the ongoing conversation in the film. Graham tells his brother that all people either believe in luck, or in miracles. While the “miracle” folks think that there’s someone taking care of them, and that no matter how bad things get at least they won’t be alone, the “luck” camp knows that they’re fundamentally on their own.

The film complicates this as it goes.

When Colleen Hess was pinned by Ray Reddy’s car, the police chief brought Graham out, and gently but firmly warned him about what he was walking into, so he could prepare himself as much as possible. After Colleen’s death, Merrill dropped whatever else he was doing to help his brother. When Tracey Abernathy wanted to confess her sins, Graham stayed and listened to her. When Graham got a call from Ray Reddy, he put the phone down, grabbed a jacket, and went out the door to meet the man. As the tone gets bleaker, the family clings together, often literally piling on top of each other on the couch in front of the TV. On a certain level, this undercuts Graham’s belief—these people aren’t alone, because they’re there for each other.

But again, there’s no sense that a cavalry is coming to help, and, at least for most of its runtime, it doesn’t allow sentimentality. At a moment when the family really seems at a loss what to do, Graham suggests with a kind of grim glee that they make a dinner of whatever they want: Bo wants spaghetti, Morgan wants french toast and mashed potatoes, Merrill wants chicken teriyaki, and Graham announces that he’s going to make a bacon cheeseburger with extra bacon. We don’t watch them make this feast, because that act of creation would undercut the tone—instead, Shyamalan cuts to the family sitting around the table in silence, food heaped in front of them. The TV is now only a blank screen and an emergency signal. Morgan wants to pray, Graham refuses to allow that, Morgan tells Graham he hates him, everyone cries, the four of them, again, collapse on top of each other.

A scene that might nod toward the resilience of the family in the face of death instead feels utterly hopeless. And it gets worse: the aliens get in, and the family has to flee to the basement, and despite barricading the entire house they’ve forgotten about a coal chute that offers a way in, they haven’t brought any weapons, Merrill knocks out the only lightbulb, they only have two flashlights, and when an alien almost gets in and Morgan has an asthma attack, they realize they forgot his medicine, too.

This family, broken down to its remaining four members, are not ready for what is happening, and no help is coming. When Graham finally cracks and says “I hate you”—not to the aliens but to God—his tone exactly matches his son’s. The scene ends with the four of them trapped in the dark, and the camera cuts to black.

Have I mentioned that every time Graham falls asleep he dreams about his wife’s death?

Still a horror movie! But in this moment, one that finds its horror not in the physical threat of aliens, but in the existential despair they’ve brought with them. Graham watched his wife die, he lost his faith and his calling, and now he’s going to watch his children and his brother die in the midst of a nightmare come true, and there’s not a goddamn thing he can do about any of it.

But this also marks the film’s turn into a very different movie! If you’ll all join me in flipping that paperback over, it’s time for Movie #2: Signs as deeply troubling religion movie.

See here’s the thing—in this movie’s reality, God (and I’m gonna just use the word God here because that’s the word the characters use) knows that there’s going to be an alien attack, and decides to intervene on humanity’s behalf. (Which, to be clear, is nice of Them!) But the intervention itself leaves a little to be desired.

Maybe every human has troubling dreams in which, I don’t know, the appropriate number of David Bowie personae hold up pieces of paper spelling out W-A-T-E-R in the mother tongue of the dreamer?

No.

Perhaps letters of fire appear in the sky, spelling out “They’re allergic to water, you dopes!!!”?

Nope.

Maybe every TV news anchor around the world is suddenly possessed and chants: “Hey! Try WATER!” in their local dialect?

Not even close.

No, what God decides to do in this scenario is to check in on small-town Episcopal minster Graham Hess and his wife, Colleen. When Mrs. Rev. Hess gives birth to her first child, God gives him asthma. When she gives birth to her second child, God gives that one a severe anxiety disorder. Years later, six months before the alien invasion, God makes sure Mrs. Rev. Hess goes for one of her late-night fog walks along a pitch-black country backroad. Then They make small-town veterinarian Ray Reddy fall asleep at the wheel of his SUV at the precise second he passes Mrs. Hess, ensuring that the poor man swerves into Mrs. Hess and pins her to a tree so that as she dies, her brain and vocal cords still work just long enough for her to say one last incredibly cryptic, seemingly meaningless message to her terrified husband.

The message?

“Tell Graham—”

“I’m here,” Graham says.

“—tell him to see, and tell Merrill to swing away.”

As she speaks, we watch soon-to-be former Rev. Hess go from thinking they’re having their last conversation, to realizing that she has no idea where she is, and is just babbling as her brain dies. This pretty much takes Rev. Hess’ faith out at the knees. Her death really messes up their kids’ emotional lives—but it also means that Rev. Hess’ former baseball phenom little brother, Merrill, comes to live with them to help out.

Six months later, as a terrifying alien kidnaps Morgan and sprays poison at the child, Rev. Hess is able to decode his wife’s message on the fly. He’s able to “see” that Merrill is standing next to his commemorative baseball bat, and tells his brother to “swing away”. And since Bo, the kid with the severe anxiety disorder, leaves cups of water all over the house, and the aliens, as I may have mentioned, are allergic to water, when Merrill swings away he splashes water all over it, and it’s incapacitated pretty quickly.

And as if that wasn’t enough forward thinking from God? Morgan’s lungs were closed when the alien sprayed him with poison—because of his asthma.

You see, it wasn’t that Mrs. Reverend Hess was reliving one of Merrill’s baseball games in her last moments as her husband believed—it’s that God was letting her see six months into the future, when her grieving family would be attacked by terrifying otherworldly creatures. And somehow, as Death wrapped its icy little paws around her, she was able to take stock of this vision, and make some lightning quick decisions about how to take the aliens out, presumably because, I don’t know, St. Peter mentioned THE WATER ALLERGY or something, and relay this message to her husband before moving on to a hopefully-alien-free plane of existence.

Don’t you feel comforted now, moviegoers?

There’s an omniscient being with enough power to micromanage the plot of this movie, but not, I don’t know—stop the fucking aliens before they get to Earth.

You’re goddamn right Graham Hess goes back to being a priest at the end—my dude’s probably afraid that if he doesn’t, God’ll plow him into a tree to save some other family in the next Divine Rube Goldberg machination.

And yet! For me this kind of makes Signs the ultimate horror film? It’s not that were all trapped in an uncaring universe, tiny pinpricks of light in an endless void. And it’s not that sheep go to heaven and goats go to hell. It’s that God actually cares about humanity, but They’re horrifically incompetent.

Either They made the aliens at some point, then made us, then moved on to another project and only just noticed at the last minute that one of their creations was about to wipe out another one—and then threw this unhinged intervention plan together like the night before it was due—or the aliens are outside of their jurisdiction somehow????

Were the aliens created by some other God, that’s more powerful than the one that intervenes on the Hess’ behalf, but had a blind spot about the water?

Are the aliens free agents who operate outside the laws of God within Their own universe?

In any case, talk about a three-body problem, amirite?

And again, did God do this with everyone on Earth? All the places where people figured out the water thing, was that God giving people a nudge in the right direction?

Or did God just take a personal interest in Graham Hess because he’s Episcopalian, and once God noticed that they were gonna be alien food, then They decided to step in?

If that’s the case, did They just do that for Episcopalians? Is this God’s way of finally telling people who got it right?

‘CAUSE THAT OPENS A WHOLE FUCKING CAN OF WORMS.

And wait, how many poor hapless bystanders were used as God’s instruments over the course of the invasion? Were other veterinarians plowed into trees? Other doomed spouses babbling cryptic warnings as they died?

Each new question opens a horrific new cosmological Matryoshka doll!

Which, if you think about it, is the magic of Shyamalan. What other creator could make a movie that is a genuinely terrifying alien invasion story, a moving meditation on grief, and a batshit work of underbaked theology?