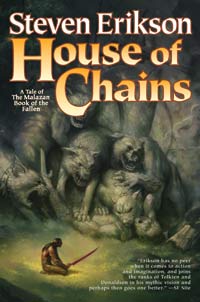

Welcome to the Malazan Re-read of the Fallen! Every post will start off with a summary of events, followed by reaction and commentary by your hosts Bill and Amanda (with Amanda, new to the series, going first), and finally comments from Tor.com readers. In this article, we’ll cover Chapter Thirteen of House of Chains by Steven Erikson (HoC).

A fair warning before we get started: We’ll be discussing both novel and whole-series themes, narrative arcs that run across the entire series, and foreshadowing. Note: The summary of events will be free of major spoilers and we’re going to try keeping the reader comments the same. A spoiler thread has been set up for outright Malazan spoiler discussion.

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

SCENE 1

Leoman’s 2000-strong force is ready to leave. Dom watches as Leoman speaks to Sha’ik, thinking he’d be just as happy if Leoman didn’t return and gloating over Sha’ik’s clear ignorance of his plans that were “settling into place to achieve her own demise.” Sha’ik reminds Leoman he is not to engage the Malazan army. Leoman tells her they’ve already probably been harassed by local tribes, but she responds those are mere skirmishes and those tribes are sending people to her everyday. Leoman’s would be easily their largest foe and she doesn’t want Tavore facing such a foe yet. Leoman agrees, then tells Heboric if he needs anything to seek out Mathok, a statement that gets both Dom’s and Sha’ik’s attention. Sha’ik calls it “an odd thing to say” since Heboric is under her protection. Leoman said he just wanted to ensure Sha’ik wasn’t distracted from preparing her army, an army, Dom points out, she entrusted Dom to run. Leoman says goodbye and as he moves away, Dom tells Sha’ik that Leoman will disobey orders. She replies, “of course he will.” Dom says he shouldn’t be allowed to leave then and Sha’ik asks if Dom is now suddenly fearful of Tavore’s army? She says Leoman’s attacks will be irrelevant; Tavore’s army is weak and shaky and young. Dom argues for keeping Leoman “leashed,” and Sha’ik says what he really means is “killed,” but if Leoman is a “mad dog” then where better to send him than against their enemy. She adds that Febryl is impatiently waiting for Dom in Dom’s tent, dismissing him cavalierly, and telling him “brittle self-importance” is a flaw in “aging men”, speaking allegedly of Febryl.

SCENE 2

After Dom leaves, Heboric asks Sha’ik if she is trying to goad the conspirators into acting though Leoman and Karsa, the only ones to trust, are gone. Sha’ik tells him she trusts none but herself. As for Leoman and Karsa, “when they look upon me they see an imposter.” Heboric asks if she trusts him, and she answer that he cannot leave now, before the battle, but afterward she will extend the Whirlwind all the way for him so as to ease his journey. Heboric asks what doesn’t she know and she replies far too much, naming L’oric specifically as a mystery, saying he can block even the Whirlwind’s magic. Heboric tells her what L’oric has revealed to him was in confidence, but he can say L’oric isn’t her enemy. She’s relieved, but when she asks if that means L’oric is her ally, Heboric doesn’t answer. She accepts that and moves on to ask about Bidithal’s “explorations” of Rashan, his old warren. Heboric and Sha’ik discuss that the Whirlwind is a fragment of Kurald Emurlahn whose “true rulers had ceased to exist, thus leaving it vulnerable,” and that the Whirlwind is the largest such fragment and it’s power is growing. She says Bidithal sees himself as the fragment’s “penultimate—[its] High Priest,” but he doesn’t know such a role doesn’t exist as Sha’ik is “High Priestess . . . single mortal manifestation of the Whirlwind.” She says Bidithal wants to “enfold Rashan into the Whirlwind” or use the Whirlwind to “cleanse the Shadow Realm of its false rulers,” the former leaders of the Malazan Empire. So many parts, she adds, to this upcoming battle, and the challenge is to “cajole all those disparate motives into one, mutually triumphant effect.” To do so, she says, she needs the secret of Heboric’s hands—they are defeating otataral and she needs to know how to do that. Heboric starts to answer she really doesn’t, as the fragment’s Elder magic will be unaffected, but Sha’ik interrupts and says Tavore will use her otataral sword to negate Sha’ik’s advantage in her High Mages. Heboric asks what that matters as Tavore can’t defeat the Whirlwind, and Sha’ik answers because the Whirlwind can’t defeat Tavore. At first this shocked Heboric, but then he realizes it makes sense as Kurald Emurlahn is so weak—in pieces, “riven through with Rashan—a warren that was indeed vulnerable to the effects of otataral.” He realizes the two magics will obviate each other, leaving it up to Dom, “who knows it and he has his own ambitions.” Heboric says he understands what she needs and why, but he has no control over the power of his hands and she says he’s getting closer because of the tea. This crushes Heboric as he had thought her suggestion of the tea for his nightmares was “compassion . . . a gift. He felt something crumbling inside of him. A fortress in the desert of my heart. I should have known it would be a fortress of sand . . . Stay? He felt no longer able to leave. Chains. She has made for me a house of chains.”

SCENE 3

At Leoman’s pit, Silgar appears and tells Felisin the warrior from Mathok doesn’t want to meet there due to concerns over prying eyes, but he is waiting for her in the ruins across the plaza. Felisin accepts the need for secrecy and follows him to the temple there, where Bidithal takes her captive. He tells her he plans to “drink all the pleasure from your precious body, leaving naught but bitterness, naught but dead places within. It is necessary . . . I take no unsavoury pleasure in what I must do. The children of the Whirlwind must be riven barren to make of them perfect reflections of the goddess herself . . . the goddess cannot create, only destroy. The source of her fury no doubt.”

SCENE 4

Silgar smiles as he hears what Bidithal does to Felisin. He thinks how Bidithal has also offered vengeance against Karsa and to raise Silgar’s place. He hears Felisin weeping and thinks “That lass would no longer look upon him with disgust.”

SCENE 5

Earlier, L’oric’s tent had briefly glowed brightly. Now, at dusk, another burst of light occurs and L’oric entered from a portal covered in blood, carrying a “misshapen beast,” an “ancient demon.” Its cries of pain had been breaking L’oric’s heart and it’s with some relief they finally end as it dies. He grieves over its death and is angry at himself for allowing it, for “too long proceeding as if the other realms held no danger to them. And now his familiar was dead, and the mirrored deadness inside him seemed vast.” As he strokes its face, he tells it “ah my friend, we were more of a kind than either of us knew. No, you knew, didn’t you. Thus the eternal sorrow in your eyes . . . each time I visited. I was so certain of the deceit. So confident that we could go on undetected, maintaining the illusion that our father was still with us.” He recalls how he had killed all the T’lan Imass involved save for the clan leader, whom he swears to hunt down. He thinks, “I need help. Father’s companions. Which one? Anomander Rake? No. A companion yes, on occasion, but never Osric’s friend. Lady Envy? Gods, no Caladan Brood? But he carries his own burdens, these days. Thus, but one left.” He calls on T’riss in “Osric, my father’s name.” He finds himself in a walled garden speaking to T’riss, Queen of Dreams. She compliments him on his skill at hiding his “Liosan traits” and says all the Tiste have gotten good at such thinks, mentioning how Rake one spent nearly 200 years disguised as a human royal bodyguard. She tells him his father Osric “Sleeps. We all long ago made our choices . . . Behind us our paths stretch, long and worn deep. There is bitter pathos in the prospect of retracing them. Yet for those of us who remain wake, it seems we do nothing but just that. An endless retracing of paths, yet each step we take is forward, for the path has proved itself to be a circle. Yet—and here is the true pathos—the knowledge never slows out steps.” L’oric tells her the Malazans call it “wide-eyed stupid.” When he informs her that Kurald Thyrllan lost its guardian, she says, “Yes. Tellan and Thyr wren ever close and now more than ever,” which he thinks is a “strange statement that he would have to think on later.” She realizes he’s there to ask her to help find a new guardian and wonders how his “desperation urges you to trust where no trust has been earned.” He argues she was his father’s friend, but she replies: “Friend? L’oric, we were too powerful to know friendship. Our endeavors far too fierce. Our war was with chaos itself, and at times, with each other. We battled to shape all that would follow. And some of us lost that battle . . . I held no deep enmity for your father. Rather, he was as unfathomable as the rest of us.” However, she agrees to help, telling him it will take a while and that “the present vulnerability will exist in the interval. I have someone in mind, but the shaping towards the opportunity remains distant. Nor do I think my choice will please you.” Her expression suddenly changes and she dismisses him, saying, “Another circle has been closed—terribly closed,” pulling her hand from a pool of blood. He appears back in his tent, sends his powers out and senses Felisin crawling in the night towards Karsa’s grove. He finds her and says he’ll go to Sha’ik, but Felisin says no; Sha’ik still needs Bidithal, a sense of priority and self-sacrifice that horrifies L’oric. She also forbids him from telling Heboric or trying to kill Bidithal. He agrees to let her stay in the grove and bring her healing elixirs. He’s furious with everyone and himself: “We knew he wanted her. Yet we did nothing.”

SCENE 6

Heboric is in his tent after several days of imbibing the tea. He has a vision of a

jade giant with a “resigned” looking expressions)flying by, then sees “scores more” emerging from a single point in the dark [lots of quotes coming up]

Each has a unique posture, they range from perfect condition to battered into fragments

He thinks “an army” at first, then notes they are “unarmed, naked, seemingly sexless”

Their “perfection” makes him think they were never alive, thus “statues in truth”

He turns to see where they are going and sees “a vast—impossibly vast—red-limned wound cut across the blackness, suppurating flames along its ragged edges. Grey storms of chaos spiraled out in lancing tendrils and the giants descended into its maw. One after another. To vanish. Revelations filled his mind. Thus the Crippled God was brought down to our world. Through this terrible puncture. And these giants follow. Like an army behind its commander. Or an army in pursuit.

He realizes they can’t all be appearing in his home realm because there are too few

He begins moving toward a giant, one that was “but torso and head.”

He can see into it: “Figures. Bodies like his own. Humans, thousands upon thousands, all trapped within the statue. Trapped and screaming, their faces twisted in terror . . . Mouths opened in silent cries—of warning, or hunger, or fear—there was no way to tell . . . He thought he understood now—they were prisoners, ensnared within the stone flesh, trapped in some unknown torment.”

He strikes the finger of another one and enters it. He:

“…found himself amidst a crowd of writhing, howling figures . . . A prisoner. There were voices roaring through his skull . . . in languages he could not recognize . . . Then a string of words reached through the tumult . . . and he understood them.

‘You came from there. What shall we find, Handless One? What lies beyond the gash?’

Then another voice spoke, louder, more imperious. What god now owns your hands, old man? Tell me! Even their ghosts are not here—who is holding on to you? Tell me!’

‘There are no gods,’ a third voice cut in . . .

‘So you say . . . in your empty, barren, miserable world!’

‘Gods are born of belief, and belief is dead. We murdered it with our vast intelligence. You were too primitive—’

‘Killing gods is not hard. The easiest murder of all. Nor is it a measure of intelligence. Not even of civilization. Indeed, the indifference with which such death-blows are delivered is its own form of ignorance.’

‘More like forgetfulness. After all, it’s not the gods that are important, it is the stepping outside of oneself that gifts a mortal with virtue—’

‘Kneel before Order? You blind fool—’

‘Order? I was speaking of compassion—’

One mentions only Heboric can leave but should do so soon while he can. Heboric looks at his missing left hand: “A god. A god has taken them. I was blind to that—the jade’s ghost hands made me blind to that.” He returns to his tent, thinking, “A god has found me. But which god?”

In them morning his hands are still “ghostly, but the otataral was gone. The power of the jade remained [with] slashes of black through it . . . barbs banded the backs of his hands. . His tattoos had been transformed.” His vision is now “inhumanly sharp” and then he realizes who the god is Treach: “In need of a Destriant, Treach? So you simply took one? Stole from him his own life . . . Is this how you recruit followers? Servants? By the Abyss, you have a lot to learn about mortals.” But his anger soon dies as he tests his heightened senses. He smells a hint of violence and blood, but dismisses it as some domestic argument. As he eats, “the burgeoning of some senses perforce took away from others. Leaving him blissfully unaware of his newfound single-mindedness. Two truths he had long known did not for some time emerge to trouble him. No gifts were truly clean in the giving. And nature ever strives for balance . . . a far grimmer equilibrium had occurred between the past and the present.”

SCENE 7

In Karsa’s grove, Felisin is awakened by serpents slithering over her. She recalls Bidithal’s words during the cliterectemy: “‘I shall bring this ritual to our people, child, when I am the Whirlwind’s High Priest. All girls shall know this in my newly shaped world. The pain shall pass. All sensation shall pass. You are to feel nothing, for pleasure does not belong in the mortal realm. Pleasure is the darkest path, for it leads to the loss of control. And we mustn’t have that. Not among our women. Now you shall join the rest, those I have already corrected.’ Two such girls had arrived then, bearing the cutting instruments. They had murmured encouragement to her . . . spoken of the virtues that came of the wounding. Propriety. Loyalty . . . the withering of desire . . . Passions were the curse of this world . . . The lure of pleasure had stolen Felisin’s mother away from the duties of motherhood.” Felisin thinks it hadn’t been pleasure but “Hood who embraced her [Felisin’s mother].” She believes Felisin will kill Bidithal, though not yet and though it may be too long until it happens: “Bidithal takes girls into his arms every night. He makes an army, a legion of the wounded. . And they will be eager to share out their loss of pleasure. They are human after all and it is human nature to transform loss into a virtue. So that it might be lived with, so that it might be justified.” Karsa’s gods awaken and Ber’ok speaks to her: “Vengeance swarms about you, with such power as to awaken us . . . We would ease your pain . . . You seek vengeance? . . . The one who has damaged you would take the power of the desert goddess for himself . . . the [Felisin’s] wounding is of no matter. The danger lies in Bidithal’s ambition A knife must be driven into his heart . . . Serve us and we in turn shall serve you . . . We shall ensure that Bidithal’s death is in a manner to match his crime, and that it shall be timely.” When Felisin asks how she is to be the knife, Ber’ok answers, “Child, you already are.”

Amanda’s Reaction to Chapter Thirteen:

Okay, so yet more emphasis of the importance of dark, shadow and light being related: “The aspect all three share is ambivalence, their games the games of ambiguity. All is deceit, all is deception. Among them, nothing—nothing at all—is as it seems.”

I do want to just remark on the fact that all these name changes do make the series unnecessarily complicated. I mean, I sort of understand the fact that a change of name is essentially a change of identity—that the name is the first step to becoming a new person—but it makes it hard. Sha’ik was Felisin, Ghost Hands was Heboric, Cutter was Crokus, Teblokai was Karsa, and other examples which I can’t think of right at this moment…. That is a LOT to keep taking on board. [Bill: By the way, I’d like to be known from now on as FarSlayer.]

I just want to highlight Sha’ik’s naivety at this point:

“Tribes will have conducted raids on them, Chosen One. Likely beginning a league beyond the walls of Aren. They will have already been blooded-”

“I cannot see such minor exchanges as making a difference either way,” Sha’ik replied.

It is clear to me that as soon as an army—especially one as green as Tavore’s—faces any sort of engagement, it will become more of a united force. The army will realise that they can survive. It will begin the Darwin process of ‘survival of the fittest’, in that those who survive the first skirmishes will automatically be more wily and more effective than those who die straight away. For Sha’ik not to recognise this shows little understanding.

Or is it that she has faith in her own forces and her own generals?

Nice little nod back to the mad dog theme that we saw at the beginning of House of Chains:

“But a wolf like Leoman should remain leashed.”

“Leashed? The word you’d rather have used is killed. Not a wolf, but a mad dog. Well, he shall not be killed, and if indeed he is a mad dog then where better to send him than against the Adjunct?”

Is it wise for Sha’ik to needle Korbolo Dom so thoroughly, especially when she has realised how much she needs him in the event that her magic is negated by the otataral of Tavore? This meeting between sisters is also magic versus the absence of magic.

Here I can see why the change of names might be useful to the author: “Ah, Ghost Hands, no we come to it, don’t we? Very well, I shall speak plain. Do not leave. Do not leave me, Heboric.” When she says Heboric, it comes across as much more vulnerable.

And then that vulnerability becomes ice—I feel for Heboric utterly when he discovers that she’s been completely manipulating him: “The tea? That which you gave me so that I might escape my nightmares? Calling upon Sha’ik Elder’s knowledge of the desert, you said. A gift of compassion, I thought. A gift… […] Chains. She has made for me a house of chains.”

Silgar has lost his name—and seemingly lost everything. This is truly sick-making…. “His sun-blistered skin was caked in dust and excrement, the stumps at the ends of his arms and legs weeping a yellow, opaque liquid. The first signs of leprosy marred his joints at elbow and knee.” Another absolutely prime candidate for the Crippled God…

Oh Gods…. Bidithal has his hands on Felisin Younger… I hardly want to turn the page. I know that sometimes Erikson’s writing descends into the darkest places, and I dread to think how far he might go here.

*makes face* “His wrinkled hands were stroking, plucking, pinching, pawing her.”

Jesus. I don’t like this. This is about the most uncomfortable I have been reading a book. I really can’t face this.

Now we find out that the creature destroyed by the T’lan Imass was, in fact, L’oric’s familiar. And here, it sounds as though L’oric is actually the SON of Osric—is that correct? [Bill: there’s a revelation, huh?] “I need… I need help. Father’s companions. Which one? Anomander rake? No. A companion, yes, on occasion, but never Osric’s friend.”

How interesting! The Tiste are able to hide their features! “Anomander once spent almost two centuries in the guise of a royal bodyguard…human, in the manner you have achieved.”

I guess we could start throwing around ideas as to who might become the protector of Kurald Thyrllan—since it is someone that won’t please L’oric, I guess it won’t be a Tiste Liosan.

Poor, poor Felisin Younger—but what strength she shows! Is it strength? Or is it a form of denial? She is most certainly thinking of her adopted mother first over herself though. Sha’ik needs Bidithal, so Felisin Younger will not mention his actions. The saddest, most real and horrible part of this is L’oric’s final thought: “We knew he wanted her. Yet we did nothing.”

We go from Felisin Younger to Heboric doing something to help Sha’ik—I’m sorry, but I really cannot see why she is inspiring this sort of loyalty, that people are prepared to suffer to make her life easier! I still don’t like Sha’ik much at all, to be honest, and her coldness and ruthlessness doesn’t help me warm to her.

What an incredible sequence! As Heboric swirls in the blackness, and observes the stars and then the drifting jade statues, I was utterly gripped. And felt a massive sense of foreboding actually: “Thus, the Crippled God was brought down to our world. Through this…this terrible puncture. And these giants…follow. Like an army behind its commander. Or an army in pursuit.” That makes me wonder slightly whether the Crippled God is as bad as he’s been made out to be, to be honest. I only say this because if I had an army of faceless, sexless jade statues that eat otataral coming for me, then I would be getting a bit worried and using what I could to defend myself…

Because, see, these statues don’t seem so friendly… “Figures. Bodies like this own. Humans, thousands upon thousands, all trapped within the statue. Trapped…and screaming, their faces twisted in terror.”

Oh, this is deliciously-written! “Killing gods is not hard. The easiest murder of all. Nor is it a measure of intelligence. Not even of civilization. Indeed, the indifference with which such death-blows are delivered is its own form of ignorance.”

Hmm, so Heboric has been stolen by Treach. And I don’t like his new single-mindedness. It takes away the introspection that was such a large part of his characters, and means that he has little interest in events outside the immediate. I think this is an immense loss.

And Felisin Younger has been damaged enough to become of great interest to the Crippled God. There are lots and lots and lots of strands emerging to this tale now!

Bill’s Reaction to Chapter Thirteen:

So “ghostly” is certainly a nice way to describe a group of white horses in the desert dust being kicked up by the Whirlwind and the animals themselves, but it’s also an interesting choice of word in terms of mood and possible foreshadowing or red herring kind of foreshadowing.

For all her fear of her sister, Sha’ik speaks a bit more confidently than I would expect when she tells Heboric that after the battle she’ll ease his journey to the jade statue.

With all that Sha’ik knows, it tells us just how good L’oric is at staying mysterious.

That is a painful scene, Heboric’s recognition of how Sha’ik has manipulated him, how what he thought had been “a gift” was in fact pure self-interest and an utter dismissal of Heboric’s own desires. Beyond the emotional impact, a few other points I liked about this paragraph:

- the use of “compassion”, which as we’ve said repeatedly is a major motif running throughout the entire series. Here, as sometimes happen, we see it brought up as its inverse.

- the metaphor of “a fortress in the desert of my heart. I should have known it would be a fortress of sand.” I love the metaphor itself, the visual of it. I like as well both it appropriateness to the context/setting (Raraku) and its echo of B’rydis.

- the use of the title, an evocative intense metaphor, the House of Chains. And this as well makes one think of others who have been forced into such a house or who have made their own.

Felisin is maybe just a little too naive/trusting in this scene, but it does also add to the horror of what happens subsequently.

More serpents in the description of the shadows.

A barren Goddess—an interesting aspect as well as motivation for fury. It also calls back Sha’ik’s discussion with Karsa earlier: “The gift of the goddess offers only destruction.”

That is a horrifying scene with Felisin obviously, but all the more horrible because there is nothing in it to necessitate it taking place in a fantasy world. Anyone seeing this as “escapist” fiction should reread this scene and explain how it can’t be a journalistic account/interview from our world right now.

“I take no unsavory pleasure in what I must do.” The justification of the depraved and sadistic forever.

L’oric’s sudden entrance and the intensity of his grief is another example of how the T’lan Imass continue to be redefined for us. We see their implacability, their perseverance, and with the Liosan we’ve met and the idea of deception, it all combines to make us think that they’re killing of the “usurper” would be a good thing, and here we see its emotional impact, the grief and sorrow they’ve engendered, all unwitting and uncaring it seems.

Did anybody else laugh at L’oric’s response to possibly going to Lady Envy? “Gods, no!”

Caladan “carries his own burdens”. Again, the metaphorical and the literal.

I don’t recall if we ever learn whom Rake was bodyguard to—anyone know offhand? Even if we don’t, I like it as a tiny bit of tapestry detail (it also reminds me of Aragorn doing the same thing in LOTR though not for so long—if I’m remembering correctly).

Behind us our paths stretch, long and worn deep. There is bitter pathos in the prospect of retracing them. Yet for those of us who remain wake, it seems we do nothing but just that. An endless retracing of paths, yet each step we take is forward, for the path has proved itself to be a circle. Yet—and here is the true pathos—the knowledge never slows out steps.”

A few ideas:

One, again, I like how this can be any person saying this, not some made up goddess in some made up fantasy world. Don’t we all know people like this—who seem to retrace their same steps, no matter where it has brought them? Haven’t we all at times wondered the same thing about ourselves?

Two—if this is the issue, the solution seems clear: break the circle. So how does this circle get broken? And by whom? Perhaps some new players in the parade are not quite so bound, might want to change the parade route a bit? Is it pure coincidence that L’oric brings up a Malazan phrase in response?

Tellann and Thyr were always close. Maybe something to watch.

I mentioned earlier that this book will deal a lot with themes of betrayal. And the other side of the coin to betrayal is loyalty and trust. We’ve seen Dom muse on his betrayal, Sha’ik talk of trust, Heboric feel betrayed by Sha’ik, Felisin betrayed and too trusting, Sinn betraying the besiegers, and here The Queen of Dreams also talks of trust.

Yes, that is a nice little tease by her re the new guardian she has in mind.

God yes, what a horrifying statement by Felisin.

And by L’oric: “We knew . . . Yet we did nothing” Another phrase that could be leveled at a host of modern issues. “…children are dying.” Look around.

The vision of Heboric is a tough one here. I’m not sure if it should be a big file and discuss later when we can do so more fully (if not completely :) ) or here. Talk amongst yourselves then and I’ll go with the gang.

Without going into the statues/Crippled God aspect, however, I will say the discussion re gods was another example of the intellectual depth one can find in these books.

And it wouldn’t be me if I didn’t, yet again, point out that line about compassion and empathy—”stepping outside of oneself”. This is, time and again, the saving grace among so much brutality we see in the series.

It’ll be interesting to watch how the Treach angle plays out for Heboric. Here’s a man who had everything taken from him, who became handless and blind—the epitome of helplessness—and now he is granted power of some sort. What will he do with it? How will he respond to it? Certainly, on a basic plot level, it will make his journey somewhat easier.

And so close to teasing out what happened to Felisin—a truly pregnant moment of plot potential that slips away. I like how Erikson handled that here.

Serpents!

Here, in Felisin’s memory, is the scene I meant when I wrote of how what happened to her could be just as easily found in a jouranlistic/memoristic account today in our world. For instance: “Pleasure is the darkest path, for it leads to the loss of control. And we mustn’t have that. Not among our women.” Anyone seriously believe this thought isn’t expressed/considered by hundreds of thousands every single day? It reminds me of something Margaret Atwood said about her novel The Handmaid’s Tale” (great novel btw—read it if you haven’t)—something along the lines of (and I paraphrase obviously): Nothing in my book is made up or fantasy, all the horrors you find in it have been perpetrated upon some people by some people in our history.

I love (obviously in the “hate” sense of “love”) the word choice too of how he has “corrected” women. That’s the precision of language—that one word tells us so much of how Bidithal views women—their potential for pleasure is a “flaw” to be “corrected.”

And I love (“hate”) that Erikson doesn’t take the easy way out here and present dirty old sick perverted how-can-you-not-hate-him scum of the Earth Bidithal as the sole perpetrator. Or men as the sole perpretrators. After all, mothers have held their daughers down, have handed them over, have been players in this scene. Yes, some out of terror for themselves and their daughters. But others out of belief. Again, it reminds me of Atwood who has her Aunts and Wives in The Handmaiden’s Tale—women as oppressors of women. It’s on the Top Ten list of oppressors—get those you’re oppressing to do your dirty work for you.

“It is human nature to transform loss into a virtue. So that it might be lived with, so that it might be justified.” Again, anyone want to argue this point? She sees pretty clearly, this young girl. Possibly, admittedly, too clearly for a young girl, but I’ll take that little bit of possibly implausibility for the intellectual stimulation and added substance any day.

Any surprise Karsa’s “gods” speak to someone now so “broken”?

This is a rough scene with Felisin, but it’s a scene as I’ve tried to highlight not only adds depth and emotional intensity and plot intensity to this story but that can be seen in the context of our own contemporary society. It isn’t the use of rape or its ilk as a cheap means of shocking the reader or of saying “hey, look how ‘gritty’ I’m being!” I appreciate Erikson’s willingness to go there.

Bill Capossere writes short stories and essays, plays ultimate frisbee, teaches as an adjunct English instructor at several local colleges, and writes SF/F reviews for fantasyliterature.com.

Amanda Rutter contributes reviews and a regular World Wide Wednesday post to fantasyliterature.com, as well as reviews for her own site floortoceilingbooks.com (covering more genres than just speculative), Vector Reviews and Hub magazine.

As Bill (Farslayer) said, we see a turn around of seeming compassion in Heboric’s “chaining” by Sha’ik. In this chapter, the dominant overt force, I would say, is Vengence. This echo’s Traveller’s taking the sword as Vengence rather than Grief in the last chapter.

We have Felisin “formed into a knife” and Sha’ik’s desire to combat her sister. We have Silgar’s twisted vengence against Karsa that leads to Felisin’s maiming.

Then, though, we see the compassion of Lo’ric for his familiar (a

Bhok‘arala I believe) this compassion in turn turns around the dispassion of the T’lan from the previous chapter.

Heboric’s view of the Jade giants falling through the gaping rift in space is fantastic. At this point it provides some info on the giants but raises more questions than it answers. What is their origin? Who are the people within? …

Bill, you can be FarSlayer if I can be ShieldBreaker.

I just want to be Nefarious Bredd . . .

@@@@@ 4

ZetaStriker wins… :-D

The Felisin younger events are one of the harder things to read, although there are plenty of them in this series. Most of the detail is kept off the pages but still we know exactly what happens and it is despicable. One only hopes that Bidithal gets what he deserves at some point.

I feel for L’oric too. His familiar is killed for no reason other than that the T’lan Imass think he is a false god. The real reason for his existence is given by L’oric. Another example of how misguided the T’lan Imass have become through their eternal vow. And then L’oric returns from that to find Felisin immediately after. The depth of his rage and hurt right then is hard to imagine.

The jade giant, Farslayer, is something I don’t see the point in filing. I’m interested to hear what people’s thoughts are now rather than waiting for more. We do get more but for me it didn’t answer many of the questions I had.

And Felisin speaking to Karsa’s gods just gave me an Aha moment that I should have recognized ages ago in connection to future events. I feel dumb right now. Wow.

The jade giants scene in here is significantly, significantly more illuminating upon a re-read than initially. I was confused as hell the first time I read that particular section. But once you’ve been through all the books and come back to it? Wow. Makes you realize that Erikson knew EXACTLY where he was going throughout the course of the series.

@Farslayer: Appropriate name when the theme is vengeance as shalter@1 points out. Like Tehol Lives@3 however, I don’t think that’s the one I’d want to be.

djk1978@6: Multiple sides to the killing of the familiar, as can be expected. After all, it was Jaghut playing god that so severely traumatized the Imass to begin with. You can’t really expect them to take a false god as a good thing. Also, are they really misguided? I would argue pretending Osseric is still there, watching and responding didn’t do the Tiste Liosan any favours. Something to consider as we go on.

Amanda: I too feel that Felesin/Sha’ik is unworthy of such loyalty and devotion. I don’t get it? She’s in this for her own revenge, and is being used and manipulated by Rel/Dom, Leoman, etc. She is selfish and hurtful to Heboric who has saved her again and again. Not a sympathetic person.

And Bidithal! Very hard to read. I kept thinking what a field day Leigh Butler would have with this section! To those of you not familiar with Leigh…is there anyone?….she blogs on Tor @@@@@ the Wheel of Time and she is an outspoken feminist….and she rages! As she should. Felesin younger is so selfless here…showing such care for Sha’ik and her mission. Amazing that anyone could.

As you say, Bill, much the same is being perpetrated in our world, today. It is common practice in certain African tribes. Argh. SE has many themes that comment on today’s trials and tribulations. It is the beauty of Fantasy, and especially SE, that we can talk about these “big” ideas, here.

I so enjoy SE’s thoughts on religion…Do we give the gods power, rather than the other way around? Do we create them? And then lose interest, so they fade away?

I am 50 pages from the end of tCG, and I can’t wait to fully engage again with the reread. HoC is soooo interesting especially having (nearly) finished the series. Much light is being shed still, in this final book, and HoC reads as a very different book now.

Chains, Compassion, Jade strangers, vengence, trust, justice……

Harai@8: The T’lan Imass issue has been discussed and will continue to be I suspect. I understand the motivations behind why they began the course they started on. However, I think the vow has ruined their ability to look at anything objectively. They don’t seem to really think anymore, they just do. And in doing they may do as much harm as good. No, I understand the Jaghut tyrants oppressed them, but it serves as little excuse for the Ritual and what the T’lan subsequently did to the other Jaghut and others in my opinion.

At this point we don’t know much about the Lioasan so you maybe right that this pretence of Osric in Kurald Thyrllan may not have been good, but I think L’oric was doing what he thought best for his fellow Liosan. Who’s to say he isn’t a better judge of that then some random T’lan Imass?

We will eventually get some introspection that many (but not all) of the T’lan are not really conscious anymore. They obey the orders they are given and react but don’t have much in the way of thinking going on.

We’ll eventually see some of the results of the failure of L’oric’s plan. How things would have progressed if L’oric’s familiar was still in place isn’t really a question we can say much about.

Shalter, nice enunciation of the vengeance theme in this chapter

Tehol–you can be Shieldbreaker if you stay away from me . . .

On the T’lan Imass, let’s not forget that they themselves have asked for oblivion to end it all. And it’s probably no coincidence that the Imass we as readers tend to bond more with are just those who most directly question what they have become. I’d also say that they quite often are presented otherwise as “certain” in their actions and intent, and we’ve seen some pretty sharp characters in these books explain the dangers of “certainty”

I’m in complete agreement that what the Tlan Imass have become is hardly perfect or even what they wanted to be. I just wanted to point out it’s not as simple as “big bad T’lan Imass wrecking everything because that’s what they do.” From their point of view, they have a very good reason to kill beings falsely portraying themselves as gods.

It’s not just a whim or caprice.

Billcap@12: On the dangers of certainty: I compare L’oric to the other Tiste Liosan at this stage and to me the only one who really has any doubts of themselves and the rightness of their actions is L’oric. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that he’s the one that knows Osseric, true Son of Father Light isn’t blessing everything they do.

Speaking of Osseric, isn’t it fun to compare and contrast the personalities and behaviors of Rake, Osseric and the other Tiste ascendant “powers” we see as we go along?

I’ve lost track of the time zones and whatnot, but heads up to the rest of you – our lovely Bill very very recently had a birthday so wish him many happy returns :-D

Happy birthday Bill!

Happy Birthday, Bill!…..and many many more!

Happy birthday Bill! Your birthday may have been a few days ago, but Farslayer was born today.

Great comments so far everyone. The t’lan imass killing l’oric’s familiar says a lot about the t’lan, about the contradiction they embody. they killed a false god, which they perceived to be the right thing to do. however, terrible, terrible things have been down with good intentions.

the full tale of the liosan after their god was killed, and jorrude and the rest returned from their ‘mission’, is one that SE doesn’t tell, but i think would be extremely interesting.

Happy birthday, Bill. Wish you a good year with many great books to read!

Happy (belated?) Birthday Bil Farslayer!

Hmm — Bill’FarSlayer

HArai @13:

I don’t know that L’Oric is very different from the other Liosan we meet in the books (Jorrude and co). Spoiler:

L’oric comes across as a self-righteous prick in TBH when interacting with mere mortals. The other Liosan have the excuse of living in a very insular society, but what excuse does L’Oric have? He has lived among humans long enough to be a little more tolerant. He is a good guy, but I wish he wansn’t so rigid.

Thanks all for the great b-day wishes.

I tried getting my wife to call my Farslayer for my birthday. Didn’t quite go over . . . :)

Happy Belated Birthday, Bill!

Actual comments on the chapter coming tonight after work ;-)

@alison: Honestly, L’Oric’s self-righteousness in TB was one of those (extremely) rare instances where I thought SE was getting preachy, and L’Oric just happened to be the mouthpiece. Or maybe it was overstated to give Scillara’s POV?

Also: Hippo Birdie, Bill!

And more betrayal in this chapter, this time one I hadn’t expected, Sha’ik betraying Heboric.

I honestly thought that old man was the one person she would keep faith with, especially after she broke down in his arms after finding out that Paran was ‘dead’.

T’riss’ musings on the way most immortals/ascendants weren’t friends and often didn’t even trust each other, only makes clear how sad it is that Whiskeyjack’s friendship with Rake was cut short.

And the Bidithal scenes were just horrendous, poor Felisin.

Following the reread again after more than a decade I felt the need to comment on the cold consideration in Sha’ik’s betrayal of Heboric in contrast to her moment of vulnerability when she heard about her brother being alive. I think we should remember that Sha’ik reborn has both the personality of a wrathful goddess in her as that of a hurt young girl named Felisin. So the betrayal might have been the goddess, and the vulnerabilty Felisin temporarily taking over?

Another thing that struck me on this reread was that Steven’s inspiration for the jade giants might have come from the Terracotta army, unearthed in the 20th century in China. The statues in that army are also all slightly different from each other (like the jade statues). Also, jade has a common association with China.