Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

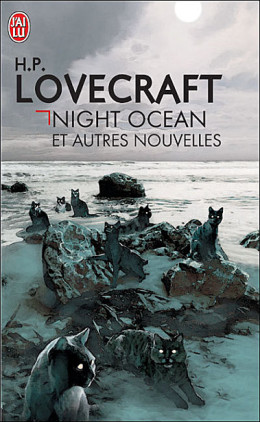

Today we’re looking at Lovecraft and R.H. Barlow’s “Night Ocean,” probably written in Autumn 1936 and first published in the Winter 1936 issue of The Californian. Spoilers ahead.

“Now that I am trying to tell what I saw I am conscious of a thousand maddening limitations. Things seen by the inward sight, like those flashing visions which come as we drift into the blankness of sleep, are more vivid and meaningful to us in that form than when we have sought to weld them with reality. Set a pen to a dream, and the colour drains from it. The ink with which we write seems diluted with something holding too much of reality, and we find that after all we cannot delineate the incredible memory.”

Summary

Unnamed artist, having completed his entry for a mural contest, wearily retreats to Ellston Beach for a rest cure. He’s a “seeker, dreamer, and a ponderer on seeking and dreaming, and who can say that such a nature does not open latent eyes sensitive to unsuspected worlds and orders of being?”

He rents a one-room house not far from the resort town Ellston, but isolated on a “hill of weed-grown sand.” The “moribund bustle of tourists” holds no interest; he spends his days swimming and walking on the beach and pondering the ocean’s many moods. At first the weather’s splendid. He combs the jetsam of the shore to find a bone of unknown nature, and a large metal bead on which is carved a “fishy thing against a patterned background of seaweed.”

As the weather turns cloudy and gray, he begins to feel uneasy. His sense of the ocean’s “immense loneliness” is oddly paired with intimations that some “animation or sentience” prevents him from being truly alone. He walks to Ellston for evening meals, but makes sure to be home before “the late darkness.” Could be his mood colors his perceptions, or else the dismal gray seaside shapes his feelings. In any case, the ocean rules his life this late summer.

Another cause for unease is Ellston’s unusual spate of drownings. Though there’s no dangerous undertow, though no sharks haunt the area, even strong swimmers have gone missing only to wash up many days later, mangled corpses. He remembers a tale he heard as a child about a woman who was loved by the king of an underwater realm, and who was stolen away by a creature with a priest-like miter and the face of a withered ape.

Early in September a storm catches him at his beach-wandering. He hurries home, drenched. That night he’s surprised to see three figures on the storm-racked beach, and maybe a fourth nearer his house. He shouts an invitation to share his shelter but the figures don’t respond, sinister in their stillness. Next time he looks, they’re gone.

Morning brings back brilliant sun and sparkling waves. Narrator’s mood rises until he comes upon what looks like a decaying hand in the surf. The sight leaves him with a sense of the “brief hideousness and underlying filth of life,” a “lethargic fear…of the peering stars and of the black enormous waves that hoped to clasp [his] bones within them—the vengeance of all the indifferent, horrendous majesty of the night ocean.”

Autumn advances. Ellston’s resorts close. Narrator stays on. A telegram informs him he’s won the design contest. He feels no elation, but makes plans to return to the city. Four nights before his departure he sits smoking at a window facing the ocean. Moonrise bathes the scene in brilliance, and he expects some “strange completion.” At last he spots a figure—human or dog or “distorted fish”—swimming beyond the breakers. With horrible ease, in spite of what looks like a burden on its shoulder, it approaches shore. “Dread-filled and passive,” he watches the figure lope “obscurely” into the inland dunes. It disappears, but he looks from window to window half-expecting to see “an intrusive regarding face.” Stuffy as the little house is, he keeps the windows shut.

The figure, however, doesn’t reappear. The ocean reveals no more secrets. Narrator’s fascination continues, “an ecstasy akin to fear.” Far in the future, he knows, “silent, flabby things will toss and roll along empty shores, their sluggish life extinct…Nothing shall be left, neither above nor below the somber waters. And until that last millennium, as after it, the sea will thunder and toss throughout the dismal night.”

What’s Cyclopean: This story’s best Lovecraftian phrases describe the ocean: “that sea which drooled blackening waves upon a beach grown abruptly strange.” “The voice of the sea had become a hoarse groan, like that of something wounded which shifts about before trying to rise.” “Recurrent stagnant foam.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Though dismissive of tourists, our narrator doesn’t pay enough attention to other people to make distinctions among them, negative or otherwise.

Mythos Making: Human-ish looking thing that swims well and skulks from the water… what on earth could that be?

Libronomicon: Our narrator is all about the visual art—and he’s trying not to even think about that.

Madness Takes Its Toll: “Night Ocean” is about 95% clinical depression and 5% possible sea monster.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

This isn’t the sort of thing I normally like. More mood than plot, much amorphous existential angst, and a lot of romantic sniffing about how sensitive our narrator is. Most people couldn’t bear the epiphanies he’s felt, y’know.

But somehow it works. Maybe because his suggestive experiences mirror things that scare us in real life. Solitude, storms, shadows where there should be none. Nothing quite crosses the line into the truly unlikely. You can imagine being there: in a seaside cottage with no real electricity and a lousy lock, nature thundering to get in. It doesn’t hurt my empathy that I had a similar getting-caught-in-a-storm experience a couple of weeks ago. Halfway through walking the dog, the torrent came down, and I stumbled home with my eyes stinging and my clothes soaked beyond the possibility of dryness. Picturing the narrator’s waterlogged sensations so vividly, everything after took on that same sheen of reality.

This collaboration comes at the very tail end of Lovecraft’s career—according to hplovecraft.com, in fact, it’s his very last work, written in Fall 1936. Barlow was Lovecraft’s friend and eventual literary executor; their co-authorship was acknowledged without any veneer of ghostwriting. You can see Lovecraft’s hand in the language, which is poetic even if thematically repetitive.

“Shadow Over Innsmouth” was complete by this point. It seems likely that the humanoid critter, alarmingly good at swimming, is no coincidence. Is Ellston Beach down the road from Arkham and Kingsport, perhaps? But while the actual observed events hark closest to “Innsmouth,” the thing the narrator truly fears is more related to “Shadow Out of Time.” The ocean, full of unknown and unknowable mysteries, is a reminder of humanity’s own mortality—of the Earth’s mortality. It’s emblematic of the universe that doesn’t much care about the rise and fall of species and planets. At some point, an entity or force that doesn’t care whether you live or die may as well be aiming for your destruction. Disinterest shades into active malice. This is possibly the most explicit statement of that theme in all Lovecraft, though “Crawling Chaos” comes close.

One thing I can’t quite get over, in spite of my overall appreciation, is our narrator’s misanthropy. As a Cape Codder, I’m required to harbor a general dislike of tourists—the sort of mild resentment inevitably born from being both dependent on them for financial stability, and having to sit through the traffic jams caused by their enthusiasm. But if there’s one thing more obnoxious than tourists, it’s the tourist who thinks other tourists obnoxious, and goes on at length about how much deeper and less frivolous he is. Man, are you here renting a cute cottage that’ll wash out to sea in the next big storm? Are you heading home when it gets a little chilly? Thought so. You’re a tourist, man, deal with it.

Though perhaps there’s parallelism here: narrator’s dismissive dismissal of the Ellston Beach tourists’ dynamic life, even as they’re killed off by malevolent force, is not so different from the uncaring ocean.

Other thoughts: Barlow himself is a pretty interesting character. Friend to Lovecraft as well as to Robert Howard, author in his own right, and active in fannish publishing. He was also an anthropologist who spoke fluent Nahuatl and did groundbreaking work translating and interpreting Mayan codices. (This is probably more important than his work with Lovecraft, but hard to learn details about at 12:30AM because the internet is written by SF geeks, not anthropologists.) He killed himself in 1951 because some jerk of a student threatened to out the man as gay. Homophobia is why we can’t have nice things. Or people. He wrote his suicide note in Mayan.

Both Lovecraft and Barlow knew something about isolation, and about hiding yourself from the eyes of men. Perhaps that’s what really gives the story its power.

Anne’s Commentary

Like others drawn into Lovecraft’s circle, Robert Hayward Barlow was a man of many talents. Writer and poet and small press publisher and editor. Sculptor. Pioneering Mesoamerican anthropologist and expert in Nahuatl, language of the Aztecs. As Lovecraft’s literary executor and former frequent typist, Barlow donated many HPL manuscripts to the John Hay Library at Brown, thus earning sainthood among Mythos scholars and the Archivist Medal of Honor from the Great Race of Yith. The latter will be presented to him sometime during the Big Beetle reign of the Yith, when Xeg-Ka’an will travel back to 1930ish to borrow Barlow’s “carapace” for a while.

Sadly, it’s supposed that Barlow committed suicide at only 32 years old when menaced not by some cosmic horror but by the threat of being outed as gay. Although, on reflection, the human capacity for intolerance may be all the horror our race will ever need to self-destruct. Only through host-Yithian eyes may we view that end of the planet Barlow imagines in “Night Ocean,” for the “silent, flabby things” will long outlive our species. I got a little chill remembering that H. G. Wells brought his Time Traveler to a similar Earth’s end, with nothing but a silent, tentacled thing still hopping on the shore under the crimson light of a dying sun and eternal night at hand.

Let’s upgrade that chill to a big one, why don’t we.

There’s no dialogue in “Night Ocean,” not a line. I suppose our narrator must speak to order meals and provisions, but we never accompany him on his brief excursions into Ellston. Instead we stay with him in his perfect solitude, on the beach, among the waves, within his odd little one-room house that’s consistently and intriguingly compared to an animal, crouching warm on its sandy hill or sitting like a small beast or hunching its back against assailing rain. The one time he speaks in-story is to sinister and unresponsive figures on the stormy beach. No, narrator’s no talker. As he writes himself, he’s not only a dreamer and seeker but a ponderer of seeking and dreaming, and what we get in his narrative is his pondering as he seeks renewed vigor on the beach—and dreams, asleep and awake, such strange, strange dreams. With effective use of poetic devices like repetition and vivid imagery, “Night Ocean” resembles such “pure” Lovecraft tales as “The Strange High House in the Mist.” With its focus on the narrator’s mental processes alone, all all alone, it recalls “The Outsider.” Lovecraftian, too, is the narrator’s sense of both insignificance and wonder before the infinite (or at least vast) and eternal (or at least as eternal as its planetary cradle) ocean. His “voice” doesn’t “sound” like the typical Lovecraft narrator, though. It’s lower-pitched emotionally—I mean, the guy can get scared without figuratively descending into tenebrous realms of demon-haunted pandemonium and all that. Plus, he never faints.

We could argue that Barlow’s narrator can afford to be calmer since his experience of the supernatural is much subtler. Significantly, he never gets any proof he’s SEEN something. No webbed footprints in the sand, no bloody handprint on the glass of his window. No photographs pinned to his canvas. Certainly no missive in his own handwriting on alien “papyrus” in an alien archive. He does pocket an enigmatic bone and an odd-patterned bead. He does see a surf-chased rotting hand. Or maybe not a hand? He’s not positive enough to report it to the authorities.

The cumulative force of the weird remains powerful, and there’s terror of the Lovecraft brand in that bit about narrator looking from window to window for a peering face. Really Lovecraftian is that wonderful line, “I thought it would be very horrible if something were to enter a window which was not closed.” But Lovecraft would have left out the “I thought.” “I thought” feels more like Barlow’s artist, doubtful ponderer that he is.

What aqueous creature, “something like a man,” does narrator glimpse loping from waves to dunes? The nudge-nudge, hint-hints that it’s a Deep One aren’t too subtle. We’ve got an ocean-delivered bead with a fishy thing and seaweed on it. We recall the Deep Ones’ skill at crafting jewelry with fishy things on it. We’ve got disappearances of strong swimmers who later wash up a bit worse for wear, and we recall how Deep Ones enjoyed the occasional human sacrifice. Then there’s the story that narrator recalls from his childhood, about how an undersea king of fish-things craved the company of a human woman, and how the kidnapper he dispatched wore a priestly miter—part of the costume, wasn’t it, of high functionaries of the Esoteric Order of Dagon?

We Mythosians know more than narrator. He’s brought no Necronomicon along for his beach read, nor even a tattered copy of Unaussprechlichen Kulten. I guess he wouldn’t know a shoggoth if he stepped on it. That’s all right. His is an eldritch-virgin’s tale, though he is a virgin constitutionally receptive to the cosmic shock, the revelation.

Besides Wells’s Time Machine, this story made me think of Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man. “Ocean’s” narrator writes: “…in flashes of momentary perception (the conditions more than the object being significant), we feel that certain isolated scenes and arrangements—a feathery landscape, a woman’s dress along the curve of a road by afternoon, or the solidity of a century-defying tree against the pale morning sky—hold something precious, some golden virtue that we must grasp.” It’s that whole epiphany thing. Stephen Dedalus was inspired to one by a girl wading in the sea, her legs delicate as a crane’s, her drawers fringed as if with soft down, her skirts dove-tailed behind her and her bosom slight and soft as the breast of a dove. Girl, bird. Wild mortal angel, goading the artist to recreate life out of life.

So Barlow’s artist sees what fleeting truth born out of the ocean? That as all things come from it, so shall they return thereto? Man, fish, an old secret barely glimpsed, not comprehended.

A last cool bit, like Barlow’s nod to Lovecraft or Lovecraft’s sardonic nod to himself or both. Narrator notes that “there are men, and wise men, who do not like the sea.” That would be HPL, the thalassophobe. But I think Lovecraft does understand those who “love the mystery of the ancient and unending deep.” Didn’t he put R’lyeh beneath it, and a certain Temple, and the glories of Y’ha-nthlei? Is it that we fear what we love, or that we love what we fear? Sometimes. Sometimes, with a painfully keen affection.

Next week, we’re gonna take a summer break. Weird, right? We’ll return to the Reread—and to a certain nameless city—on August 18th with John Langan’s “Children of the Fang,” which appears in Ellen Datlow’s Lovecraft’s Monsters anthology.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.