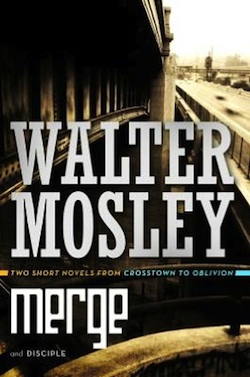

We have excerpts from Walter Mosley’s upcoming novel: Merge/Disciple, two works contained in in one volume. It’s out on October 2:

Merge: Releigh Redman loved Nicci Charbon until she left him heartbroken. Then he hit the lotto for $26 million, quit his minimum wage job and set his sights on one goal: reading the entire collection of lectures in the Popular Educator Library, the only thing his father left behind after he died. As Raleigh is trudging through the eighth volume, he notices something in his apartment that at first seems ordinary but quickly reveals itself to be from a world very different from our own. This entity shows Raleigh joy beyond the comforts of $26 million dollars…and merges our world with those that live beyond.

Disciple: Hogarth “Trent” Tryman is a forty-two year old man working a dead-end data entry job. Though he lives alone and has no real friends besides his mother, he’s grown quite content in his quiet life, burning away time with television, the internet, and video games. That all changes the night he receives a bizarre instant message on his computer from a man who calls himself Bron. At first he thinks it’s a joke, but in just a matter of days Hogarth Tryman goes from a data entry clerk to the head of a corporation. His fate is now in very powerful hands as he realizes he has become a pawn in a much larger game with unimaginable stakes a battle that threatens the prime life force on Earth.

Merge

There ain’t no blues like the sky.

It wasn’t there a moment before and then it was, in my living room at seven sixteen in the evening on Tuesday, December the twelfth, two thousand seven. I thought at first it was a plant, a dead plant, a dead branch actually, leaning up against the wall opposite my desk. I tried to remember it being there before. I’d had many potted shrubs and bushes in my New York apartment over the years. They all died from lack of sun. Maybe this was the whitewood sapling that dropped its last glossy green leaf just four months after I bought it, two weeks before my father died. But no, I remembered forcing that plant down the garbage chute in the hall.

Just as I was about to look away the branch seemed to quiver. The chill up my spine was strong enough to make me flinch.

“What the hell?”

I could make out a weak hissing sound in the air. Maybe that sound was what made me look up in the first place. It was a faltering exhalation, like a man in the process of dying in the next room or the room beyond that.

I stood up from the seventeenth set of lectures in the eighth volume of The Popular Educator Library and moved, tentatively, toward the shuddering branch.

My apartment was small and naturally dark but I had six-hundred-watt incandescent lamps, specially made for construction sites, set up in opposite corners. I could see quite clearly that the branch was not leaning against the wall but standing, swaying actually, on a root system that was splayed out at its base like the simulation of a singular broad foot.

The shock of seeing this wavering tree limb standing across from me had somehow short-circuited my fear response. I moved closer, wondering if it was some kind of serpent that one of my neighbors had kept for a pet. Could snakes stand up straight like that?

The breathing got louder and more complex as I approached.

I remember thinking, Great, I win the lotto only to be killed by a snake nine months later. Maybe I should have done what Nicci told me and moved to a nice place on the Upper West Side. I had the money: twenty-six million over twenty years. But I didn’t want to move right off. I wanted to take it slowly, to understand what it meant to be a millionaire, to never again worry about work or paying the bills.

The sound was like the hiss of a serpent but I didn’t see eyes or a proper mouth. Maybe it was one of those South American seed drums that someone had put there to scare me.

“Nicci?” I called into the bedroom even though I knew she couldn’t be there. “Nicci, are you in there?”

No answer. She had sent my key back two years before—a little while after she left me for Thomas Beam.

Even though I was facing this strange hissing branch the thought of Tom Beam brought back the stinging memory of Nicci asking me if I minded if she went out to a show with him.

“He’s just a friend,” she’d said. “He’s not interested in me or anything like that.”

And then, two months later, after we had made love in my single bed her saying, “I’ve been sleeping with Tommy for six weeks, Rahl.”

“What?”

“We’ve been fucking, all right?” she said as if I had been the one to say something to make her angry.

“What does this mean?” I asked.

I knew that she hadn’t been enjoying sex with me. I knew that she was getting ready to go back to college and finish her degree in business; that she was always telling me that I could do better than the filing job I had with the Bendman and Lowell Accounting Agency.

“Do you love him?” I asked.

“I don’t know.”

“Are you going to keep seeing him?”

“For a while,” Nicci Charbon said. “What do you want?”

It was just after midnight and my penis had shrunk down to the size of a lima bean; the head had actually pulled back into my body. My palms started itching, so much so that I scratched at them violently.

“What’s wrong?” Nicci asked.

“What’s wrong? You just told me that you’re fucking Tommy Beam.”

“You don’t have to use foul language,” she said.

“But you said the word first.”

“I did not.”

We went back and forth on that fine point until Nicci said, “Well what if I did say it? You’re the one who told me it was all right to go out with him.”

“I . . .” It was then that I lost heart. Nicci Charbon was the most beautiful girl . . . woman I had ever known. I was amazed every morning I woke up next to her and surprised whenever she smiled to see me.

“I don’t want to lose you, Nicci,” I said. I wanted to ask her to come back to me but that seemed like a silly thing to say when we were in bed together in the middle of the night.

“You don’t care about me and Tommy?” she asked.

“I don’t want you to see him.”

It was the first bit of backbone I showed. Nicci got sour faced, turned her back, and pretended to sleep.

I tried to talk to her but she said that she was too upset to talk. I said that I was the one that should have been upset. She didn’t answer that.

I sat there awake until about three. After that I got dressed and went down to Milo’s All Night Diner on Lexington. I ordered coffee and read yesterday’s newspaper, thought about Nicci doing naked things with Tom Beam and listened to my heart thudding sometimes slowly, sometimes fast.

When I got back at six Nicci was gone. She’d left a note saying that it would probably be better if we didn’t see each other for a while. I didn’t speak to her again for fifteen months. Most of that time I was in pain. I didn’t talk about it all that much because there was no one to talk to and also because we were at war and a broken heart seems less important when you have peers that are dying from roadside landmines.

And then I won the lotto. Nicci called me three days after it was announced.

“No,” she said when I asked about her new boyfriend. “I don’t see Tommy all that much anymore. We were hot and heavy there at first but then I started college and he went to work for Anodyne down in Philly.”

She called me every day for two weeks before I agreed to see her. We had lunch together and I didn’t kiss her when we parted. She wanted to see me again but I said we could talk on the phone.

I wanted to see her, that was for sure. She looked very beautiful when we got together for lunch at Milo’s. She wore a tight yellow dress and her makeup made her wolf-gray eyes glow with that same hungry look that they had the first night she came up to my place.

But what was I supposed to do? Nicci had dropped me like an anchor, cut the rope, and sailed off with another man.

And now there was this seed drum or serpent hissing in my room.

A four-inch slit opened in the stick toward where the head would be if it was a snake or a man. The opening was the length of a human mouth, only it was vertical and lipless. A rasping breath came from the thing and I heard something else; a sound, a syllable.

I saw then that it couldn’t have been a stick because it was undulating slightly, the brown limb showing that it was at least somewhat supple—supporting the snake theory.

I leaned forward ignoring the possible danger.

“Foo,” the limb whispered almost inaudibly.

I fell back bumping against the desk and knocking my nineteen-forties’ self-study college guide to the floor. It was a talking stick, a hungry branch. Sweat broke out across my face and for the first time in nearly two years I was completely unconcerned with Nicci Charbon and Thomas Beam.

“What?” I said in a broken voice.

“Food,” the voice said again, stronger now, in the timbre of a child.

“What are you?”

“Food, please,” it said in a pleading tone.

“What, what do you eat?”

“Thugar, fruit . . .”

My living room had a small kitchen in the corner. There was a fruit plate on the counter with a yellow pear, two green apples, and a bruised banana that was going soft. I grabbed the pear and an apple and approached the talking stick. I held the apple up to the slit in the woodlike skin. When the fruit was an inch from the opening three white tubes shot out piercing the skin.

The apple throbbed gently and slowly caved in on itself. After a few minutes it was completely gone. The tiny pale tubes ended in oblong mouthlike openings that seemed to be chewing. When they were finished they pulled back into the fabulous thing.

“More?” I asked.

“Yeth.”

The creature ate all my fruit. When it had finished with the banana, peel and all, it slumped forward falling into my arms. It was a heavy beast, eighty pounds at least, and warmer by ten degrees than my body temperature. I hefted it up carrying it awkwardly like the wounded hero does the heroine in the final scene of an old action film.

I placed the thing upon my emerald-colored vinyl-covered couch and watched it breathing heavily through its vibrating slit of a mouth.

The living branch was round in body, four and half feet long. It was evenly shaped except for the bottom that spread out like a foot formed from a complex root system. The vertical slit was open wide sucking in air and it seemed to be getting hotter.

“Are you okay?” I asked, feeling a little foolish.

“Yessss.”

“Do you need anything?”

“Resssst.”

For a brief moment a white spot appeared at the center of the brown tube.

It gave the impression of being an eye, watching me for a moment, and then it receded into the body of the creature as its tubular mouths had done.

“Ressst,” it said again.

Disciple

I opened my eyes at three thirty on that Thursday morning. I was wide awake, fully conscious. It was as if I had never been asleep. The television was on with the volume turned low, tuned to a black-and-white foreign film that used English subtitles.

A well-endowed young woman was sitting bare breasted at a white vanity while a fully dressed man stood behind her. I thought it might be at the beginning of a sex scene but all they did was talk and talk, in French I think. I had trouble reading the subtitles because I couldn’t see that far and I had yet to make the appointment with the eye doctor. After five minutes of watching the surprisingly sexless scene I turned off the TV with the remote and got up.

I went to the toilet to urinate and then to the sink to get a glass of water.

I stood in the kitchen corner of my living room/kitchen/ dining room/library for a while, a little nauseous from the water hitting my empty stomach. I hated waking up early like that. By the time I got to work at nine I’d be exhausted, ready to go to sleep. But I wouldn’t be able to go to sleep. There’d be a stack of slender pink sheets in my inbox and I’d have to enter every character perfectly because at the desk next to me Dora Martini was given a copy of the same pink sheets and we were expected to make identical entries. We were what they called at Shiloh Statistics “data partners” or DPs. There were over thirty pairs of DPs in the big room where we worked. Our entries were compared by a system program and every answer that didn’t agree was set aside. For each variant entry we were vetted by Hugo Velázquez. He would check our entries and the one who made the mistake would receive a mark, demerit. More than twentyfive marks in a week kept us from our weekly bonus. Three hundred or more marks in three months were grounds for termination.

I climbed the hardwood stairs to the small loft where I kept my personal computer. I intended to log on to one of the pornography Web sites to make up for the dashed expectations the foreign film had aroused.

I was already naked, I usually was at home. It didn’t bother anybody to see a nude fat man lolling around the house because I lived alone. My mother would tell me that at my age, forty-two next month, I should at least have a girlfriend. I’d tell her to get off my back though secretly I agreed. Not many of the women I was interested in felt that they had much in common with a forty-two-year-old, balding, data entry clerk. I’m black too, African-American, whatever that means. I have a degree in poli sci from a small state college but that didn’t do much for my career.

At least if I was white some young black woman might find me exotic. As it was no one seemed too interested and so I lived alone and kept a big plasma screen for my computer to watch pornography in the early or late hours of the day.

I turned on the computer and then connected with my Internet provider. I was about to trawl the Net for sex sites when I received an instant message.

Hogarth?

Nobody calls me that, not even my mother. My father, Rhineking Tryman, named me Hogarth after his father. And then, when I was only two, not old enough to understand, he abandoned my mother and me leaving her alone and bitter and me with the worst name anyone could imagine. I kept saying back then, before the end of the world, that I would change my name legally one day but I never got around to it, just like I never got around to seeing an ophthalmologist. It didn’t matter much because I went by the name of Trent. My bank checks said “Trent Tryman,” that’s what they called me at work. My mother was the only living being who knew the name Hogarth.

Mom?

For a long while the screen remained inactive. It was as if I had given the wrong answer and the instant messenger logged off. I was about to start looking for Web sites answering to the phrase “well endowed women” when the reply came.

No. This person is Bron.

This person? Some nut was talking to me. But a nut who knew the name I shared with no one.

Who is this?

Again a long wait, two minutes or more.

We are Bron. It is the name we have designated for this communication. Are you Hogarth Tryman?

Nobody calls me Hogarth anymore. My name is Trent. Who are you, Bron?

I am Bron.

Where are you from? How do you know me? Why are you instant messaging me at a quarter to four in the morning?

I live outside the country. I know you because of my studies. And I am communicating with you because you are to help me alter things.

It was time for me to take a break on responding. Only my mother knew my name and, even if someone else at work or somewhere else found out what I was christened, I didn’t know anyone well enough to make jokes with them in the wee hours of the morning. Bron was definitely weird.

Listen, man. I don’t know who you are or what kind of mind game you’re playing but I don’t want to communicate with you or alter anything.

I am Bron. You are Hogarth Tryman. You must work with me. I have proof.

Rather than arguing with this Bron person I logged off the Internet and called up my word processor.

I’d been composing a letter to Nancy Yee for the last eight months that was nowhere near completion. The letter was meant to be very long. We’d met at a company-wide retreat for the parent corporation of Shiloh Statistics, InfoMargins. The president of InfoMargins had decided that all employees that had more than seven years of service should be invited regardless of their position.

The retreat was held at a resort on Cape Cod. I liked Nancy very much but she had a boyfriend in Arizona. She had moved to Boston for her job and planned to break up with Leland (her beau) but didn’t want to start anything with me until she had done the right thing by him.

She’d given me her address and said, “I know this is weird but I need the space. If you still want to talk to me later just write and I’ll get back in touch within a few days.”

She kissed me then. It was a good kiss, the first romantic kiss bestowed on me in over a year—way over a year. I came home the next day and started writing this letter to her. But I couldn’t get the words right. I didn’t want to sound too passionate but all I felt was hunger and passion. I wanted to leave New York and go to Boston to be with her but I knew that that would be too much to say.

Nancy had thick lips and an olive complexion. Her family was from Shanghai. Her great-grandparents came to San Francisco at the turn of the twentieth century and had kept their genes pretty pure since then. She didn’t think herself pretty but I found her so. Her voice was filled with throaty humor and she was small, tiny almost. I’ve always been overlarge but I like small women; they make me feel like somebody important, I guess.

I composed long letters telling Nancy how attractive and smart and wonderful she was. I decided these were too effusive and deleted them one after the other. Then I tried little notes that said I liked her and it would be nice to get together sometime. But that showed none of my true feeling.

That Thursday morning at five to four I opened the document called “Dear Nancy” and started for the ninetyseventh time to write a letter that I could send.

Dear Nancy,

I remember you fondly when I think of those days we spent at the Conrad Resort on the Cape. I hope that you remember me and what we said. I’d like to see you. I hope this isn’t too forward . . .

I stopped there, unhappy with the direction the letter was taking. It had been eight months. I had to say something about why I’d procrastinated for so long. And words like “fondly” made me seem like I came out of some old English novel and . . .

Hogarth?

I looked down at the program line but there was no indication that the system was connected to the Internet. Still the question came in an instant message box. There was a line provided for my response.

Bron? What the fuck are you doing on my computer? How are you on it if I’m not online? I don’t want to hear anything from you. Just get off and leave me alone.

It is of course odd for you to hear from someone you don’t know and cannot accept. I need for you, friend Hogarth, to trust me and so please I will give proof if you will just agree to test me.

What are you trying to prove?

That you and I should work together to alter things.

What things?

That will come later after you test me, friend Hogarth.

Test what?

Let me tell you something that no one else could know. Something that may happen tomorrow for instance. An event.

Fine. Tell me something that you couldn’t know that will happen tomorrow.

Something you couldn’t know, friend Hogarth. At 12:26 in the afternoon a report will come from NASA about a meteorite coming into view of the Earth. They think that it will strike the moon but about that they are mistaken. It will have been invisible until 12:26. It will be on all news channels and on the radio. 12:26. Good-bye for now, friend Hogarth.

When he signed off (I had no idea how he’d signed on) I was suddenly tired, exhausted. The message boxes had disappeared and I couldn’t think of anything to say to Nancy Yee. I went back downstairs and fell into my bed planning to get up in a few moments to go to Sasha’s, the twenty-four-hour diner on the Westside Highway, for pancakes and apple-smoked bacon.

The next thing I knew the alarm was buzzing and the sun was shining into my eyes. It was 9:47 A.M.

I rushed on my clothes, skipping a shower and barely brushing my teeth. I raced out of the house and into the subway. I made it out of my apartment in less than eight minutes but I was still an hour and a half late for work.

“Ten thirty-eight, Trent,” Hugo Velázquez said before I could even sit down.

“My mother had a fever last night,” I told him. “I had to go out to Long Island City to sit up with her. I missed the train and then the subway had a police action.”

I could have told him the truth but he wouldn’t have cared.

The data entry room was populated by nearly all my fellow workers at that late hour. The crowded room was filled with the sound of clicking keyboards. The data enterers were almost invariably plugged into earphones, hunched over their ergonomic keyboards, and scowling at the small flat-panel screens.

The Data Entry Pen (as it was called by most of its denizens) was at least ten degrees warmer than elsewhere in the building because of the number of screens and cheap computers, bright lights and beating hearts. There were no offices or low cubicle dividers, just wall-to-wall gray plastic desktops offering just enough room for an inand outbox, a keyboard, and a screen.

Of the sixty-odd data entry processors half turned over every year or so; college students and newlyweds, those who wanted to work but couldn’t manage it and those who were in transition in the labor market. The rest of us were older and more stable: losers in anyone’s book. We were men and women of all ages, races, sexual persuasions, religions, and political parties.

There were no windows in the Data Entry Pen. Lunch was forty-five minutes long conducted in three shifts. We used security cards to get in, or out. On top of protecting us from terrorists these cards also effectively clocked the time we spent away from the pen.

I sat down at my terminal and started entering single letter replies from the long and slender pink answer forms that Shiloh Statistics used for the people responding to questions that we data entry operators never saw. “T” or “F,” one of the ABCs, sometimes there were numbers answering questions about sex habits or car preferences, products used or satisfaction with political officials.

“We put the caveman into the computer,” Arnold Lessing, our boss and a senior vice president for InfoMargins, was fond of saying. He’d done stats on everyone from gang members to senators, from convicts to astronauts.

At the bottom of each pink sheet there was a code number. I entered this after listing all the individual answers separated by semicolons without an extra space. After the code I hit the enter key three times and the answers I entered were compared to Dora’s . . . I usually made about twice as many mistakes as she did.

Merge/Disciple © Walter Mosley 2012