Metropolis (1927) Directed by Fritz Lang. Screenplay by Thea von Harbou. Starring Alfred Abel, Brigitte Helm, Gustav Fröhlich, and Rudolf Klein-Rogge.

Before we get into this week’s film, I’m going to take a brief detour into discussing modern art. I would ask for your patience, but I figure if you have patience enough to spend two and a half hours watching a 97-year-old silent movie, you also have the patience to enjoy a short—and relevant!—art history lesson.

Through the latter half of the 19th and into the beginning of the 20th century, there were major changes happening in the Western art world. These changes were happening across all artistic media, not just in the visual arts, but the visual arts are an easy shorthand for demonstrating the shift. Artists were moving away from classical styles that had dominated the previous few centuries (think: the Dutch Golden Age, the Italian Renaissance, the Baroque movement) and exploring more experimental, less traditional approaches to creating art.

This didn’t happen by accident. The artists of the era, which includes everybody from Van Gogh with his star-filled sky to Seurat with his Sunday afternoon to Munch with his eternally relatable scream, were deliberately experimenting with new ways to create art: to capture people and places, to convey emotions and ideas, to do so in ways that hadn’t been done before. A lot of these experiments involved various degrees of abstraction—that is, setting aside literal representation, clear perspective, and visual logic in favor of impression, emotion, distillation, simplification. At its farthest extreme of abstraction are the things that tend to get labeled (often dismissively) as modern art (e.g., the Abstracts, the Dadaists, the Cubists), but there was in fact a very broad spectrum of movements and styles spreading across Europe and the U.S. during the first decades of the 20th century (…not just the ones that make dads in museums snort derisively and remark that anybody could do that).

One of those movements was Expressionism, whose artists were interested in exploring radically subjective, highly emotional views of the world. Our buddy Edvard Munch’s The Scream is the perfect example of an Expressionist work: it doesn’t look like a realistic or accurate portrait of a person, but it sure as hell feels like a mood that everybody recognizes all too well. Another example, which I share simply because I love it so much, is Franz Marc’s Deer in the Forest, which captures the color-saturated, geometrically disjointed feeling of looking upon a scene of sunlight filtering through a thick forest cover. But there weren’t only painters interested in this style of interpreting and portraying the world. There were also writers, sculptors, dancers, and, yes, filmmakers.

In 1916, right at the heart of World War I, Germany banned the import of foreign films, which led to a wartime bounty of German-made films going into production. And, yes, a lot of these films were government-sponsored propaganda, but not all of them were, and by the time the war ended and the ban was lifted, Germany had all the necessary components of a major film industry. But they also had trade embargoes that now went in the other direction, as the rest of the world was balking at watching German movies. All of these factors combined to create a brief, concentrated, semi-isolated, and wildly creative explosion of German movies during the years of the Weimar Republic. That period of intense production fell off abruptly when the Nazis rose to power and began declaring anything even remotely interesting degenerate and illegal, and filmmakers, actors, and artists from all corners of Germany’s film industry fled the country.

But right in the middle of all that inter-war creative period were the German Expressionists, a movement of avant-garde artists across all disciplines keen on exploring subjective, emotional perspectives on the world, with particular interest in the very dark reality of postwar Germany and the ominous rise of unchecked industrialization. In cinema, the quintessential example of German Expressionism is Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), which combines gorgeous and discomfiting surrealist artistry with a horror premise of an evil doctor brainwashing a sleepwalker into committing murders, as a way of exploring ideas of authority, tyranny, and violence.

All of that is the cultural context Metropolis comes out of.

The screenplay for Metropolis was based on a novel of the same name, which Thea von Harbou wrote for the specific purpose of it being adapted into a film by Fritz Lang. Von Harbou and Lang were married at the time; in addition to Metropolis, they collaborated on several films together, including Woman in the Moon (1929), one of the earliest “serious” sci fi films ever made, and M (1931), one of the first about the hunt for a serial killer. Both their marriage and their professional collaborations would end in 1933, the year Adolf Hitler came to power and put Joseph Goebbels in charge of the newly-established Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. The final film Lang and Von Harbou made together was The Testament of Dr. Mabuse, a thriller about a mad criminal mastermind. Lang had to screen the film for Goebbels, who banned it in Germany for portraying how a group of “extremely dedicated people” might overthrow a government with violence. At some point thereafter, Lang made the decision to leave Germany for France, and eventually became a naturalized citizen of the United States, while von Harbou stayed behind and later became a member of the Nazi Party.

When you read up on Metropolis anywhere, from the most in-depth articles to the briefest summaries, you very quickly encounter the oft-repeated story that Goebbels admired Metropolis so much he wanted Lang to make Nazi films, and Lang hated this idea so much he packed up that very night and fled the country instead. That is more or less how Lang told the story a decade or so later, although it seems like he took some rather dramatic license in this retelling. Film historians still actively debate how much of it is true. But Lang was definitely anti-Nazi, and would later make multiple specifically anti-Nazi films, the most famous being Man Hunt (1941), which the Hollywood censors working under the Hays Code criticized because it didn’t offer “balance” in its portrayal of the Nazi antagonists.

And all of that is the political context that has largely defined the legacy of Metropolis.

So now that we’ve established this complicated framework for the film—a work of Expressionist modern art released during the pivotal post-WWI period but often interpreted through a post-WWII lens—let’s get into the film itself.

First, a note on the many, many versions of this film: The only version of Metropolis I have seen is the restored version that was released in 2010. This is the one that was reconstructed after a complete copy of the original cut was found in a museum in Museo del Cine in Buenos Aires. When I first looked into it, I was kind of expecting the story of the discovery of the original negatives to be somewhat dramatic, but as far as I can tell it was very tame. The negative had been in Argentina for decades (in the form of a safety reduction of the original nitrate stock), and it had passed from a distributor to a private collector to a museum. In 2008 the curator of the museum learned they had this copy of lying around, located it, and got it to the right people to authenticate and restore it.

Prior to that restoration, there were numerous versions and cuts of the film over the years (including one from the ’80s with a rock soundtrack), with the various degrees of editing going all the way back to immediately after its initial release in 1927. The reasons for the countless versions include people, companies, and governments deciding along the way that it was too long, too confusing, too communist, too radical, too incomplete, or (apparently) too lacking in ’80s rock music, but the key point is that until that lost copy was found in 2008, everybody who recut or reedited Metropolis was working with incomplete versions pieced together from the hack job Paramount made when they edited the film for American distribution.

The restoration finished in 2010 is not a wholly complete version of Lang’s final cut, as some parts of the film remain too damaged to use, but it’s the most complete it has been since its brief run in Berlin in 1927. It is available with the full original (and very Wagnerian) score by Gottfried Huppertz, which was also used to determine where certain missing bits went and how long they lasted.

I share this because it’s a fascinating bit of film history—and because it is a very strong argument in favor of preserving all the physical media you can. Don’t throw your physical media away, folks.

Metropolis is set in a futuristic city that has no other name, because it isn’t meant to be any specific place; it’s simply meant to be a city, perhaps any city, in an unspecified time period. In this city, society is rigidly stratified between the workers who live and toil in hardship beneath the surface and the elite masters who frolic in gardens and attend lavish parties above. We are introduced to the city’s residents in a very telling order, because we see the machines before we see any humans. Only after a lingering introduction to the chugging, churning labyrinth of steam engines do we meet any people, and they are the anonymous and downtrodden workers, in dark clothes with their heads lowered, moving about in featureless clusters. They are, visually and metaphorically, another part of the machine, one that needs to be replaced at every shift change.

From there we move to the city above, where the rich and powerful have created a haven for their sons, a garden where these fortunate young men enjoy leisure and education and chasing scantily clad women around fountains. That’s what our main character is doing when we meet him. Freder (Gustav Fröhlich), son of the city’s master Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel), is interrupted in his frivolities by the arrival of some visitors from the workers’ city. A beautiful young woman (Brigitte Helm) is escorting a group of the workers’ children to witness the city’s elite sons in their natural habitat. The two groups of people stare at each other like both of them think the other is an exotic zoo animal, with the exception of the young woman, Maria, who pointedly tells the poor children that the rich heirs are their brothers and sisters.

Freder has never before seen a pretty girl radicalize schoolchildren right in front of his fountain, so he naturally becomes obsessed and heads down to the underground city to search for her. But instead of finding Maria, he finds the hall of massive machines, where he witnesses a terrible accident that kills several workers. Dazed by the explosion, Freder has a vision of the machine as a temple of Moloch, the Canaanite god of fire who, in the Old Testament’s Book of Leviticus, is associated with forbidden practices that are implied to be human sacrifice. A metaphor that unsubtle does not need to be explained to either the audience or poor, dazed Freder. When he comes to, he races out of the workers’ city and goes straight to his father.

The visual contrast between the different parts of the city is pronounced and very interesting. The buildings of the workers’ city are plain and utilitarian, every one of them looking the same, with minimal ornamentation or decoration; everything is boxy and sliced by intense, angular shadows. But both the hall of machines and the masters’ city above are different. These are where we see the stunning Art Deco design that Metropolis is rightfully famous for. Lang was inspired in creating the look of the city by a visit to New York. He made that visit in in 1924, a few years before some of New York’s most famous art deco skyscrapers were complete (eg., the Empire State Building and Chrysler Building), but there were already skyscrapers enough to put the idea of a tall, bright, dense, multilayered city in Lang’s mind. The machines, and especially the Heart Machine that drives them all, are also beautifully designed and ornate.

Many of the large buildings in Metropolis are miniatures, and while working on the film cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan developed a technique for filming live actors in scenes with the model cityscapes. The Schüfftan process, as it came to be known, involved placing a plate of glass at a 45-degree angle between the camera and the actors on the set and marking out where the action occurred on the glass. The glass was then replaced with a mirror, with the position of the actors removed so that the camera would still record them. The building miniature would be placed to the side of this viewline, and the camera would film the reflection of the miniature in the foreground with the actors in the distance—creating the effect of small characters set into a large building, in other words. I know it sounds confusing, but it’s actually extremely clever in how simple it is: you can see a diagram of the setup up on this page. The Schüfftan process became largely obsolete when it became easier for films to use traveling matte backgrounds and bluescreens for large-scale scenery and backgrounds.

Back in Metropolis, Freder tells his father about the deadly accident in the machine hall. Fredersen is not terribly moved by the deaths of the workers; he is more concerned about the mysterious maps the machine foreman (Heinrich George) found in the pockets of the dead men. Disappointed that his heartless industrialist of a father is behaving like a heartless industrialist, Freder heads back to the workers’ city to see how the other half lives. To his credit—and the film’s—his motivation does seem to be the plight of the workers, and only a little bit about Maria. He swaps places with a worker (Erwin Biswanger), and after a grueling shift he is able to accompany the other workers to finally locate Maria.

While Freder is enduring his first ever day of work, his father is trying to learn what the maps found with the dead workers mean. This is where the film takes a delightfully gothic turn—because, after all, what is more gothic than a mad inventor living in a forgotten church and trying to achieve Frankenstein-like miracles of science by creating a robot to take the place of his lost love? There is nothing more gothic than that, except perhaps a crazed man chasing a pretty young woman through some dark catacombs.

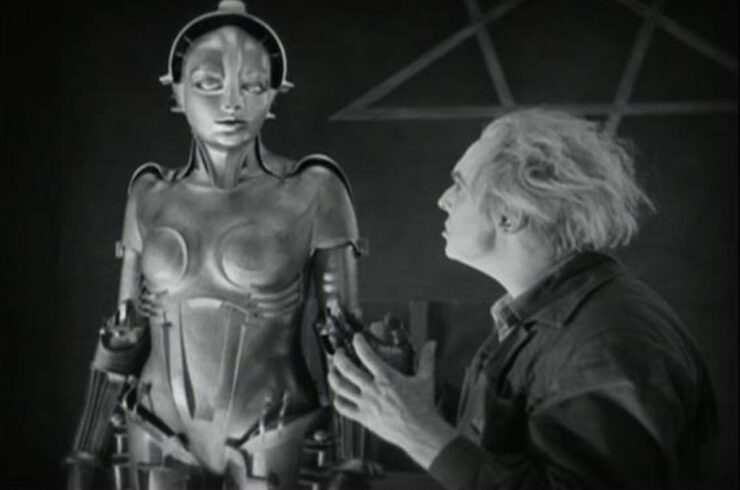

Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge), the inventor, wants to bring the dead beloved Hel (Fredersen’s wife and Freder’s mother) back to life by giving her face to his robotic invention (called the “Maschinenmensch” in German). Fredersen is not terribly happy about this invention, at least not yet. He and Rotwang follow the maps from the dead workers into the catacombs beneath the city, where they see Maria (surrounded by crosses and candles) sharing a version of the story of the Tower of Babel to convince the workers they deserve better treatment from their masters. Upon hearing this, Fredersen tells Rotwang to put Maria’s face on the robot instead. He wants to use Maria’s likeness to encourage the workers to violence, which will both discredit Maria and give Fredersen an excuse to retaliate and crush any thoughts of an uprising. So that’s exactly what they do. Rotwang abducts Maria in the catacombs, puts her face onto the robot, and sets the robot loose in the city to wreak havoc.

The Maschinenmensch (which is never given another name in the film) was designed by sculptor Walter Schulze-Mittendorff. He built the costume around a full-body cast of Brigitte Helm, and although he used a pliable plastic wood-filler instead of actual metal, it was very painful for her to wear. It looks incredible, though; there is a reason that eerie, elegant design is still so iconic.

But even more striking to me is Helm’s performance as the false Maria. Even when the robot looks human, there is something so very off, so powerfully off-putting about Helm’s expressions and motions, that the robot is instantly recognizable as a completely different being from Maria. Helm was only seventeen years old when she filmed Metropolis; it was her first movie and was, by all accounts, an arduous and unpleasant production that lasted eighteen months. She went on to act in several more movies over the span of about a decade—but none with Lang—then retired from acting completely in 1935 because she hated the Nazi takeover of German’s film industry. She married an opponent of the Nazi Party, moved out of Germany, and never acted again.

Helm may only be remembered for this one role, but what a performance it is! Those feverishly distorted scenes where the robot dances at the club, the wicked glee on her face when the men in the audience begin to fight, her smiling fascination when the angry mob burns her at the stake—she’s brilliant, she’s changeable, and she never looks human. Her performance is exactly as enthralling and unsettling as it should be.

The false Maria incites the workers to violent dissent and the wealthy party-goers to violent debauchery, and the final act of the film consists of a whole lot of frightening mobs of people running around in different places. That includes a crowd of workers’ children, abandoned to drown by their rioting parents. This fact is not remotely fun: The children were played by several hundred actual impoverished, undernourished kids from the poorest parts of Berlin, who spent some two weeks filming in cold water to complete those flooding scenes in the workers’ city.

The climax of the film is as gothic as can be. The angry mob burns the false Maria at the stake; Rotwang attempts to abduct the real Maria because he believes her to be his beloved Hel; Freder fights Rotwang on top of a cathedral. Because you can’t go full gothic unless somebody has a fight on top of a cathedral. After Rotwang falls to his death, Freder convinces his father to join hands with the machine foreman, thereby fulfilling Maria’s goal of linking the “head” of the city with its “hands” by becoming its “heart.”

If you’re thinking that it’s a far too simplistic ending for a film that touches on several very complex social and political problems, well, you’re not alone. Decades later, Lang would tell Peter Bogdanovich in an interview that he simply wasn’t thinking very deeply about the politics at the time, and most of the film’s theme came from von Harbou. He acknowledges that the idea that the “heart” of a society can link its “head” and “hands” is pretty much a fairy tale. His interest was in the machines, in the rapid industrialization and technological advancement that characterized the first decades of the 20th century. But, over all, Lang hated Metropolis: “I didn’t like the picture—thought it was silly and stupid—then, when I saw the astronauts—what else are they but part of a machine? … Should I say now that I like ‘Metropolis’ because something I have seen in my imagination comes true—when I detested it after it was finished?”

I don’t think Metropolis is silly or stupid, although I do agree that the social politics at its core are more than a little troubling—especially the division of society into thinkers and workers. But there are also gems of astute observation in there: how easy it is to convince people to act against their own (or their children’s) self-interest, how eagerly the powerful will manipulate the powerless for their own purposes, how readily those who commit violence blame the victims of their violence for making them do it. The film has been interpreted as everything from pro-communist to pro-fascist with many stops in between, and I think part of the reason for the variety of readings is the coexistence of those “silly” elements right alongside those incisive observations.

But we’re still talking about it today, because as a nightmarish, alarming, and fascinating exploration of a single city that represents a larger, critically imbalanced society, it is utterly compelling. The obsession with technological progress, the dehumanization of labor, the stark contrast between visible beauty and hidden cruelty, the looming presence of a city that has pockets of both madness and hope tucked away, this is what all the best science fictional visions of the future are built on.

That brings me back to where I started, with a reminder to myself that Metropolis comes out of a time period and an artistic movement that was not trying to portray the world accurately, logically, or rationally—the things that we expect in science fiction, which is often very straightforward in its representation of an imagined world, even if that world is metaphorical or allegorical. What Metropolis wants to do, most of all, is to make its audience feel. Awe and anxiety, grief and fear, hope and suspicion—it wants to make its audience feel all the things that humans feel in a rapidly changing and uncertain world.

What do you think about Metropolis, the oldest film we’ve watched so far? What do you think about its portrayal of technology and progress? Where are your favorite places to see its influence in different sci fi movies that followed? Share your thoughts below!

Next week: We went full catacomb gothic this week, so let’s go full detective noir next week with Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville. Pull out your library card to watch it on Hoopla or Kanopy, or go to YouTube and find a video of the right length, or check various streaming services around the world, because the availability of this one varies widely.