I’m fond of found-object and assemblage art. I love that one person’s trash is another person’s robotic mouse. Micmacs à tire-larigot is like that, an assemblage of rusty refuse bits made into a delightful new mechanism.

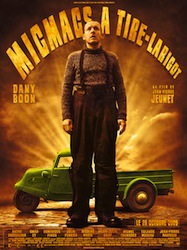

Jean-Pierre Jeunet, French screenwriter, director and producer who brought us Delicatessen, City of Lost Children, Amélie and other films has most recently created Micmacs. It is, if you can believe it, a magical, light-hearted and charming story of revenge against arms manufacturers. It’s also a reflection on the paranoia and fragility of corrupt people in power, and demonstrates the strength of playful subversion.

The title is a peculiar one. Micmac, in English, usually refers to a Native American nation, but in French slang (as far as I can tell) it means something similar to its false cognate mishmash. I’ve seen the title translated a number of ways, from “plentiful problems” to “a lot of conundrums” and “non-stop madness” but I get the impression that it’s just not a phrase that translates directly. That said, it fits the nature of the film despite, or perhaps because, it is puzzling.

Protagonist Bazil, as a child, lost his father to a landmine and, as an adult, was shot in the head by a stray bullet. After his injury he lost his job and apartment, and tried his hand at being a street performer. He’s taken in by a small family-like group of other outcasts who work as garbage salvagers. He soon discovers that the arms manufacturer who made the landmine that killed his father is across the street from its rival, the manufacturer of the bullet that remains lodged in his head. With the help of the salvagers, he sets up multiple plots of mischief against the arms dealers.

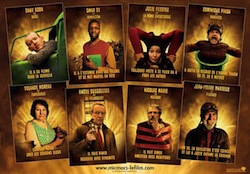

If you’ve seen Amélie, you’ll no doubt remember how she undermined the sanity of the mean shopkeeper by changing his lightbulbs and shoes and creating other silly nuisances. Micmacs takes this idea much further. The salvagers in their fight against the arms manufacturers remind me of a superhero group taking on super-villains, but substituting super for quirky. Each member has some beneficial oddity, from a diminutive strong man to a Guinness World Record-obsessed daredevil to a rubbery contortionist to a human calculator and a writer who speaks almost exclusively in cliché. Each fits improbably but perfectly in the schemes, like an odd cog or lever in what is essentially a massive Rube Goldberg machine of a film.

Micmacs is as visually immersive as any of Jeunet’s films. With his love of woolen browns and dingy greens and greasy grays, it’s a darker look than Amélie but considerably less oppressive than the visual weight of City of Lost Children.

Dany Boon (Bazil) is a well-known comedy actor in France, though not very famous elsewhere. I hope that Micmacs can change that, bringing him well-deserved notoriety, as Amélie did for Audrey Tautou. Micmacs is whimsical treat and Boon’s Chaplinesque delivery is responsible for no small part of the enchantment.

When Jason Henninger isn’t reading, writing, juggling, cooking or raising evil genii, he works for Living Buddhism magazine in Santa Monica, CA