Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

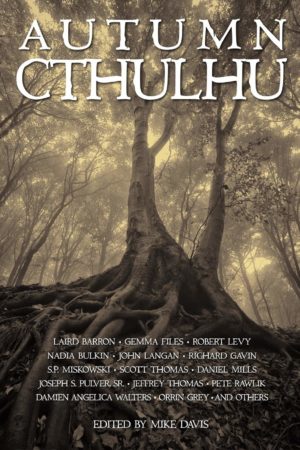

This week, we cover Gemma Files’s “Grave Goods,” first published in the 2016 Autumn Cthulhu anthology. Spoilers ahead!

“It’s a boogeyman, so it has to do something gross. Like giants grinding bones to make their bread.”

As Aretha Howson fits bone chips together, they sing in a tone she feels more than hears, a frequency that “whispers in her ear at night, secret, liquid. Like blood through a shell.”

Aretha works with Drs. Elyse Lewin and Anne-Marie Begg of Lakehead University in Ontario, Canada. Through a miserably wet October, Lewin’s team has been investigating a site on Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug First Nations land. The location’s remote and wild; the team had to cut a path through old growth conifers to reach their goal: a granite slab incised with petroglyphs atop a burial pit dated to 6500 B. P. (before the present). They’ve named it “Pandora’s Box.” A member of the local tribe, Begg has helped secure the elders’ permission to excavate.

The slab, it turns out, is also inscribed on its underside with “square-cut, coldly eyeless faces.” Begg calls the topside petroglyphs votive totems, but confesses they don’t resemble those she grew up with. Aretha speculates the topside may say “Keep out,” the underside “Stay in.”

A month into the dig, Aretha’s battling sinusitis as well as irritation with everyone except fellow intern Morgan. Lewin assembled an all-female team with the apparent belief that this exclusion of testosterone would guarantee harmony and cooperation. Nope: Begg and forensics expert Tatiana Huculak constantly battle over Huculak’s desire to send bone samples off-site for carbon-dating. Forget it, Begg says. The human remains must be returned to their resting places, as found. Huculak counters that she’s not sure the remains are human. Their pelvises are backslung like a bird’s, their spines articulated like a snake’s, their eyes set on the sides of their heads, their too-many teeth carnivore-pointed and -serrated. Maybe they’re looking at an “offshoot of humanity…some evolutionary dead end.” Debate deteriorates into what Begg calls “the black girl and the Indian, calling each other out as racists.” Lewin’s reminders that they’re all scientists, respectful professionals, have no lasting effect.

Aretha’s glad none of the team knows she’s trans. Paranoid, maybe, but there’s tension enough already. And puzzles, like why a family burial (one male, one female, one unsexed adolescent) should be exorbitantly blanketed with grave goods. Like why both skeletons and goods are coated with the red ochre that in ancient burials worldwide symbolized blood, propitiation, a warding-off of vampiric ghosts. Like why despite that reverent avalanche of grave goods, the skeletons’ faces were desecrated. She wonders too about the common practice, apparently absent here, in which the prominent dead were buried with sacrificed retainers.

One day, as light fades, Aretha feels driven back to the excavation. En route she overhears Begg on the sat-phone, arguing with an elder about Huculak’s suspicions. Begg doesn’t want to muddy their scientific undertaking with “mythology.” Aretha remembers the “fairy tales” Begg initially told them over the campfire. Her people don’t go where they’re now working, which is why it was a hiker who found the slab. Legend has it that Baykoks lingered here: skeletally thin creatures that shrilled in the night, killed warriors, and devoured their livers.

Aretha continues to the pit and scrapes obsessively at its walls. Morgan finds her and summons the others. Over their protests, Aretha digs on. Finally Begg realizes Aretha must’ve heard her earlier phone call. The Baykok’s folklore, she says. Aretha’s not going to find any separate larder of human bones. Aretha was thinking about retainer sacrifices, but there might be both. What about Huculak’s theory? What if a species coexisted here with humans and interbred, so modern humans might retain traces of the other species’ DNA?

Suddenly the pit wall collapses, spilling “roots and stones and bones, bones, bones” over Aretha. She was right, she deliriously thinks. “They’re here, we’re…(here).” And above her, behind her shocked team members, stands a tall, thin figure with burning side-set eyes. Its wail fills her mind: “(here, yes) (as we always have been) (as we always will)”

Buy the Book

What Feasts at Night

Aretha awakes in the main tent, “hurt all over, inside and out,” a “furled agony-seed” in her lower abdomen. With Aretha’s clothes removed for first aid, the team’s discovered the scars from her gender reassignment surgery. Lewin’s incensed with the “misrepresentation,” but Morgan hotly defends Aretha. Begg and Huculak fall into their old argument. Huculak brandishes a freshly uncovered human bone which still has unmummified flesh on it. Morgan insists on hiking down-trail to find a sat-phone connection and call in medical help for Aretha. She kisses Aretha and whispers that she’ll see her soon, but the voice in Aretha’s mind hisses “I—(we)—think not.”

Aretha drifts off. She wakes to lessened pain and goes out into a blessedly rainless night, where Lewin, Begg, and Huculak huddle around a Coleman stove. Morgan has been gone two or three hours. Five minutes down the trail, Begg finds tracks, which all go to see. Each narrow print wells with blood and is, by human standards, backwards. Begg recalls legends about the Baykok: how at first they used humans for food, then slaves, then breeding stock. “Sometimes,” she allows to Huculak, “a monster isn’t a metaphor for prejudice… Sometimes it’s just a monster.”

That tone, “like blood through some fossilized shell,” again thrums through Aretha, drawing nearer. She sinks down, hears Lewin call out Morgan’s name. But it’s not Morgan who approaches. It’s her skin, held “like an early Hallowe’en mask” before a skeletal shadow flanked by others “making their stealthy, back-footed way towards them all.” Aretha’s inner voice whispers that “this darkness is yours as much as ours…passed down…from our common ancestors…”

Every grave is our own is Aretha’s last thought. The earth opens and she falls, wondering who will eventually find her bones, who will hear their songs, how long this time “before anyone stops to listen.”

What’s Cyclopean: The piercing cry of the baykok is “shell-bell, blood-hiss. Words made flesh, at long last.”

Libronomicon: Sure Heinrich Schliemann used The Iliad as a guidebook to find Troy—or something that could be called Troy—but that doesn’t mean that old epics are usually the best way to pick archaeological sites.

The Degenerate Dutch: Huculak says some deeply rude things about Begg’s insistence on protecting ancestral (or not-so-ancestral) bones, and about indigenous people generally. Lewin is an ass when Aretha is revealed to be transgender, and gets appropriately shouted down. Also it turns out that making an expedition all-female does not actually prevent conflict.

Weirdbuilding: Some of the stories feeding into weird fiction are very, very old.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

One of the most traditional horror stories is about what happens if you stray past the light of the campfire, or break binding social norms. Don’t go out thataway, there are monsters (maybe tigers, maybe dragons). Be polite to strangers on the road, they might punish rudeness (with a sword, with magic). And don’t mess with the dead.

As we’ve become more prone to messing with the dead—because they’re someone else’s ancestors and we’re curious, or because they’re buried with ancient jewels, or because medical research requires—the stories have expanded to gloss our nervousness. Doctors Frankenstein and West need corpses to control the stuff of life, and pyramids are surely full of both treasure (not actually yours) and curses (as many as you can carry). As for the trope-standard “Indian burial ground,” well. European-descended North American cultures are maybe not entirely reconciled to living on the bones of apocalypse.

Files’s archaeologists do have advantages over Indiana Jones. They’re actually checking with the original keepers of the land, for a start, even taking a representative along. They’re more interested in proper scientific procedure than treasure. They plan to treat the dead with respect.

No matter who you are—no matter how respectful you are of what you think you’re dealing with—you dismiss the old stories at your peril.

We’ve read several stories about a prejudiced jerk who ultimately gets eaten by a grue, or occasionally and unfortunately who gets the grue to eat others. This one is more interesting: a group of people with strong opinions and intersecting marginalities, who fail just badly enough at listening to stories—their own and others’—to fall prey to the grue whose bones they’re trying to study. None of them are irredeemable jerks, even Huculak with her anger at indigenous restrictions on disinterment or Lewin with her TERFy tendencies. Put them in a warm room with hot tea, and they could probably work out their differences or at least discuss them with less swearing—but they’re not going to get that chance.

The closest any of them come to taking the Baykok story seriously, before the end, is calling the slab “Pandora’s Box.” They half-joke about symbols reading “keep out” and “stay in,” but they aren’t listening to themselves. They’re scientists, after all, and part of science is looking for the evidence in front of you rather than believing stories. If you’re in the wrong sort of story, though, you’ll find more of that evidence than you can handle.

I love that amid all this, they are scientists. They care passionately and sometimes exasperatingly about research methods. They talk in citations and references and comparisons, debating the similarities and differences between baykoks and wendigos, making inferences based on the cross-cultural frequency of retainer sacrifice. They trace etymology and the genetics of the genus Homo. They point out that giants could grind your bones to make flatbread but not anything that has to rise. I hate when narratives treat scientists as idiots for being themselves in the face of genre threats (looking at Michael Chrichton here); here the mismatch between curiosity and imminent grue seems more tragedy than judgment.

I do have to admit that I spent the whole story wanting to hug Aretha and make her go lie down. It’s possible that some things would’ve worked out better if she’d been sent home on her first day of fever, or at least that Morgan wouldn’t have gotten eaten first. Or that they would’ve gotten to kiss? Maybe? Unfortunately, I suspect something would’ve woken the baykoks anyway, and no one here seems like an obvious Final Girl with a chance at survival. Perhaps Aretha would’ve gotten some painkillers for the whole ordeal, at least. The line that made me squirm the most was the description of her “world’s worst yeast infection,” which is presumably imminent grue possession, but ow. Ow ow ow. I’ve never had my liver torn out and am just fine with avoiding it, but that’s the bit I can imagine all too easily.

Anne’s Commentary

Weird fiction wisdom holds that if the native or local people do not go to a certain place, your band of explorers or research scientists or adventure vacationers should not go there either. Invariably, the outsiders ignore this red flag. Invariably, it’s because native and local people are the dupes of legend, superstition or wrong-headed custom. Scooby-Doo variation: The natives and locals are making up monsters to scare outsiders off from some resource, treasure or evidence of nefarious deeds. Scooby-Doo variations aside, the natives and locals are always right, and at least some of the outsiders pay the ultimate price for their hubris.

In “Grave Goods,” Files gives us a character straddling the divide between natives and outsiders. Begg belongs to the tribe whose members avoid legendary Baykok territory, but she’s also an outside-trained scientist. In the end she admits that she knew about the Baykoks; she just didn’t want to believe the stories were true, even after Huculak found evidence that there might be something to them. Sciency evidence, you know, like bone and teeth structures more avian and reptilian than human. Oh, Science, you double-edged scalpel, you pusher of carbon-dating and DNA analysis that must finally drive us mad or into the comfortable ignorance of a new dark age!

Because who really wants to know where we came from, if we came from there too recently, anyhow? It’s one thing to picture evolutionary change occurring over millions of years, phylogenetic trees putting out branches and twigs and twiglets far more slowly than any actual plant. It’s another to think of Baykoks and humans interbreeding only about 6500 years ago, to produce an Aretha Howson in the present day: Someone entirely human from the looks of it, but hiding the Baykok within flesh, cartilage, and bone that resonate to its kins’ monstrous voices.

That’s assuming, of course, that there are monsters and not just differences individual to individual, race to race, species to species and on up the taxonomic hierarchy. I think everyone on Lewin’s team would have agreed pre-expedition that it’s prejudice that creates monsters, justifying one’s fear of particular others by demonizing them. Begg’s terrified realization is that “sometimes a monster isn’t a metaphor for prejudice at all, plus or minus power. Sometimes it’s just a monster.”

We’re not sure exactly what Lewin meant to accomplish by selecting only women for the Pandora’s Box project. Aretha deduces from the professor’s initial pitch that Lewin genuinely believed an all-female team would guarantee an operation free from “ambition, wrath, or lust,” a “paradisiacal meeting of hearts and minds.” But as Aretha’s aunties used to say, “Just ‘cause they ain’t no peckers don’t mean ain’t no peckin’ order.” The clash between Begg and Huculak is based on legitimately incompatible agendas. That doesn’t stop them from peppering their arguments for and against bone analysis with racial innuendoes and even slurs. Lewin flutters at such unprofessional (and unsisterly) behavior, but when Aretha’s transgender status is exposed, so too are Lewin’s biases.

Since such relatively minor differences are enough to shatter the harmony of the expedition, it’s a good thing no one has a chance to appreciate Aretha’s kinship with the Baykoks, who are to her not a “them” but a “we.”

Which brings up the question I often ask myself: Self, why in weird fiction do so many nonhuman intelligences want to interbreed with humans? And how can they even do so, given the substantial genetic differences between the species? Fantasy can fall back on magic, I suppose, science fiction on technology. Files’s scientists mention interbreeding between Neanderthals and Homo habilis, but these two groups must be much more closely related than humans and Baykoks. From the skeletons Lewin’s team unearths, the Baykoks sound like a reptilian-avian mashup. That suggests dinosaurs to me, since among the reptiles are dinosaurs and among the dinosaurs are birds. What if some dinosaur line survived to alter through convergent evolution into a vaguely anthropomorphic form? That would still leave Baykoks and humans too distantly related for interbreeding, wouldn’t it?

Never mind my overthinking. Baykoks, like all “reptile-people,” are cool creations. Maybe they’re related to the “Nameless City” serpents? And maybe that “adolescent” skeleton found under Pandora’s Box, with its “missing” pelvis, was a more ophidian form of Baykok? Or a visiting relative from the Arabian desert?

I’ll stop now, I swear.

Next week, we face the cracks in the sky in Chapters 17-18 of Max Gladstone’s Last Exit.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of A Half-Built Garden and the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon and on Mastodon as [email protected], and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.