Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

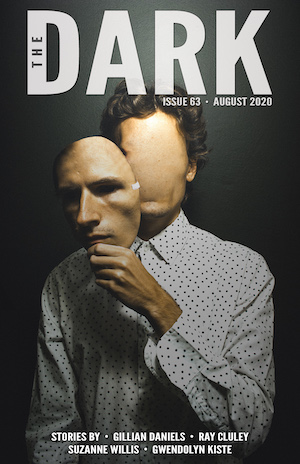

This week, we’re reading Gillian Daniels’s “Bobbie and Her Father,” first published in the August 2020 issue of The Dark. CW for harm to children.

“Nancy has a grasp like the weight of paper.”

Bobbie has spent ten years inside her house, blackout curtains drawn, TV playing. She likes watching movies, especially with dancing. Sometimes she tries to immitate their flying leaps, or tries; with one leg longer than the other, she can manage little more than hops.

This morning, while Bobbie industriously eats protein powder straight from the can, a woman knocks on the front door. Bobbie’s father has told her to respond ignore visitors, but curiosity wins out this time–Bobbie’s never spoken to a real woman. She lumbers to the door.

The woman’s eyes widen at the sight of Bobbie, but she introduces herself as Nancy, an adjunct in Dad’s department. He’s told Nancy so much about Bobbie! Is he home? Bobbie lets Nancy shake her hand, but her palm slickens with sweat. Nancy asks if she’s all right. Bobbie’s father has told her about–the accident.

Nancy leaves, and Bobbie rushes to wash her hands for fear of germs. When Dad arrives home, she’s excited to tell him about Nancy, but one of her nosebleeds delays conversation. They need to do some “work” first.

Work means a trip to the slab in the garage. Bobbie follows Dad, envying the fluid way he walks on legs that grew with his body. She doesn’t want to ask for a replacement foot–Dad doesn’t like to discuss how he found the pieces to make her. She lies on the slab, looking up at stars through the skylight. Her father takes up a scalpel, looks at an X-ray of Bobbie’s piecemeal skull. He remarks that when he was a surgeon, it was stressful, all those life and death decisions. As he cuts into her face (which lacks pain receptors), Bobbie knows if he could, he’d take death out of the equation altogether.

Stitched back up for the hundredth time, Bobbie asks about the danger of contamination from Nancy’s visit. Dad admits he was only guessing that Bobbie had to self-isolate all these years; he was being cautious. His egotism enrages her, this man who named his daughter after himself, who thinks he’s too good for death. She could crush his skull if she wanted, but knows she’d regret it bitterly, like the time she tried to free a blackbird from their attic and inadvertently crushed it.

Buy the Book

Star Eater

So she goes to bed, to pretend she sleeps like normal people. What would she do outside, she wonders. Touch grass? Inspected the rusted swing-set? Walk down the street until someone screamed?

Next morning Dad makes a conciliatory breakfast and says Nancy and her son will be coming over later. It’s time Bobbie started interacting with real people. Both procede to fuss around the house all day, anxious and excited.

Nancy arrives alone, explaining that Travis has gone to his father’s for the weekend. Bobbie watches how she hugs Dad, jokes with him. Do they want to date? She’s glad Nancy sits next to her, talks to her, seems to like her. They discuss movies, and Bobbie sings a bit from The Music Man. Nancy, astonished, says Bobbie has a wonderful voice. Dad agrees.

Then Travis shows up, falling-down drunk. He tells Bobbie her “mask” is nice, then realizes his mistake with little contrition. Bobbie supposes he’s one of those wild teenage boys represented on TV, but he’s also cool and gorgeous.

Mortified, Nancy leaves to call Travis’s father. Dad follows, leaving Bobbie alone with the only other man she’s ever met. Travis notes her uneven legs; she’s uncomfortable, but flattered to be looked at. When Travis heads outdoors to “take a leak,” he brushes against her shoulder, notices how muscular she is. Yes, she’s strong, Bobbie says. Thinking to imitate Nancy’s flirtatious smacks at Dad, she gently pushes Travis out the door.

He rolls on the grass, howling she’s hurt him. Guilt-wracked, Bobbie takes her first ever step outside, only to have Travis mock her for buying his faked injury. Her heart breaks that this rebellious, gorgeous boy thinks she’s stupid, and she asks why he lied. He answers that, because she’s going to hate him eventually, she might as well start now.

It’s like learning Dad lied about the germs, only worse. Rage fills her. If Travis wants Bobbie to hate him, she will. She grabs his arm. She thinks of her father piecing her together, then lying about what she could do with that patchwork body.

She twists Travis’s arm out of its socket, tears it away from his body. Blood jets on the grass. Travis screams and screams. Bobbie hears Nancy calling—Nancy, who won’t be her friend now. She picks up Travis, and his severed arm, and hurries into the garage. She did this, a thing much worse than the blackbird, and now she’ll fix it. She’ll work, like Dad.

As Bobbie clamps and stitches, Travis goes still and cold. Nancy demands that Dad unlock the garage. She shakes the doorknob, while Dad insists that the kids can’t have gone in there.

Bobbie keeps stitching. When she’s done her best, she’ll wait for Travis to move. She may not remember the first moments of waking up, but wasn’t she there from the beginning?

She’s her father’s daughter, and there’s work to be done.

What’s Cyclopean: The descriptions of Bobbie’s experience of her imperfectly-constructed body are vivid despite being painless. Blood is a “viscous, oozing” syrup that stains a tissue “with frayed, red spots like the dark roses on the bathroom wallpaper.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Nancy brings up The Music Man as a favored musical—“it was a bit sexist, I guess, but the songs are just so much fun.” (This is true. It’s also, relevantly, a story about someone pretending to be something he isn’t, and having to redeem the deception.)

Weirdbuilding: Frankenstein is a powerful source to play with, and this week’s story leverages that power well.

Libronomicon: Bobbie reads—she mentions reading books by women in particular—but learns most about the world (some of it accurate) from The View, Good Morning America, and many, many dance shows and costume dramas.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Travis seems to have serious problems, even before he meets Bobbie. And Bobbie’s family isn’t the only one hiding things.

Anne’s Commentary

Many people convert their garages into workshops where they can practice their hobbies. This is a good idea. It keeps noise and dust and paint spatters and noxious odors out of the house proper, and the cars can sit outside just fine. Unless, of course, your hobby is fancy cars, in which case you need a really big garage, or several.

Bobbie’s dad Rob can make due with one garage, because his hobby isn’t fancy cars but fancy reanimations of the classic Frankensteinian variety–that is, of a patchwork pattern, like crazy quilts. Crazy quilts can be quite beautiful, but it’s a gamble, and they may not wash well. Stitches pulled through unrelated fabrics can come loose, mismatched seams can fray. But since Rob only has one quilt to deal with, he has time to tweak and make repairs.

Still, reanimation via heterogeneous reassortment is tricky. You can’t send to Etsy for a starter kit or have Amazon deliver replacement feet overnight, free shipping to Prime members. Setting up a home surgical theater isn’t cheap. Neighbors, door-to-door solicitors and repair people must be guarded against. Then there’s the heterogeneous reassortment herself.

So far Rob’s been a very lucky reanimator with Bobbie. Look at all the trouble Victor Frankenstein had, and Herbert West, and even salts-master Joseph Curwen. For the ten years since her awakening, Bobbie’s been an obedient daughter, never stirring outside their close-curtained house, content to learn about reality from the dubious shadow-world of television and movies. She’s believed what her father tells her about bacterial hazards and the ultimate capabilities of her body. She’s been considerate of his feelings, trying not to let him hear her clumsy dancing or to demand “work” beyond what he volunteers to provide.

For all her awkwardness and scars, Rob can call Bobbie a success. The brain in her odd-lots skull works well. During her pseudo-childhood, she’s reached at least an adolescent’s understanding and education. She’s shown a talent for singing. She thinks sharply. She observes closely. She feels acutely. Too acutely for her own and her father’s comfort at times, but what teenager doesn’t? All Bobbie needs to take her next developmental step is real-world experience with sympathetic real-worlders.

Here’s the catch. The real-world and monsters rarely mix well. That’s why Rob’s sealed Bobbie in a controlled world for so long. Even if he were only an arrogant egotist seeking to conquer death for the glory of it, he wouldn’t want to risk his sole subject through premature exposure. I read Rob as more than this particular monster-maker trope. He seems to have quit his surgical practice for emotional reasons, an inability to cope with life-or-death decisions. But if he were constitutionally unable to cope, would he have ever practiced surgery? I’m thinking some traumatic event knocked him out of the profession. I’m thinking the same event flung him into reanimation.

Bobbie’s father is controlling. Bobbie’s father has told her big lies. But as with “normal” controlling and sometimes-dishonest parents, that doesn’t mean he doesn’t love her. Maybe he loves her too much now because he loved her too much before, when he couldn’t let her go.

I’m basing my case on an object Daniels mentions in deft passing, with Bobbie putting no more emotional weight on it than she does the backyard grass and fence: Also in the backyard she’s never entered is–a rusty swing set. Long enough ago for the set to rust, a child played in Rob’s backyard. Say it was ten years ago, plus however many years stretched between lost and found, between a Bobbie dead and a Bobbie-of-sorts reborn.

There’s also that picture of Bobbie Rob keeps on his phone. I assumed, as Bobbie does, that it’s a picture of her as she looks now; more likely it’s a picture of the original Bobbie, a cute-kid photo Nancy could legitimately admire. To prepare Nancy for what now stands for Bobbie, Rob made up an “accident” story–maybe one based on an actual accident, only a fatal one.

Do I speculate? I do, because Daniels’s story is both spare enough and rich enough to invite such reader participation. It opens at the moment of change in Bobbie’s existence: Nancy’s knock on the door. Rob’s given Nancy enough encouragement to visit. Lonely himself, he wants to believe this affable adjunct will be just the sympathetic “real” person Bobbie needs to progress. He could have been right, too, if another teenage monster in the form of Travis hadn’t shown up.

Poor misunderstood monster Travis, who’s drunk enough to tell Bobbie the truth about his bad behavior: Let’s not pretend you could ever like me but get the rejection done now. Poor misunderstanding monster Bobbie, who’s too emotionally naïve to recognize his flash of vulnerability.

What follows is the shocking violence presaged by Bobbie’s memory of the trapped blackbird. And then comes Nancy’s second attack on a door, not gentle this time, and copious room for speculation on what must follow it for Bobbie—and her father.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Everyone has their hot-button rants. Conversations about technology and ethics are at serious risk of hitting one of mine: if anyone cites Frankenstein as a warning against scientific arrogance and playing god, and my Mary-Shelley-loving heart spits out a five-minute rant about how that isn’t the point of the story. That original genre-birthing tale—one of the world’s perfect tragedies despite a Romantic Angst dial that goes up to 11—is absolutely not about the hubris of R&D. It is, much to the distress of generations of misogynistic critics, covered in girl cooties: it’s all about the responsibilities of parenting, and the horror of neglecting them. Dr. Frankenstein makes new life, is disgusted by what he’s made, and leaves his philosophically-minded creation to make his lonely way in a world that teaches him only violence. And violence, it turns out, is something he can learn.

Daniels gets it.

Bobbie, unlike Frankenstein’s Adam, has a father who loves her. It’s enough to delay the tragedy. His flaws are less all-encompassing, harder to articulate, and I think more forgivable. Should he have sheltered Bobbie more, keeping her from contact with ordinary humans until he was truly sure of her self-control and ability to understand the consequences of her action? Or should he have sheltered her less, giving her a wider range of experiences that would help her understand those things?

Along with that all-too-ordinary parental quandary comes another conflict that doesn’t drift far from reality. Rob recognizes and loves Bobbie as a thinking, feeling person much like himself—and often fails to recognize and offer empathy for the places where she isn’t like him. The scene where he fixes her face, and can’t quite get through his head that she’s not going to feel pain, is heartbreaking. “Don’t you believe me?” The idea that people are all people and that we still aren’t all hurt by the same things can be a tough lesson even under normal circumstances. (Whatever the hell those are.)

As his flaws are fundamentally the flaws of an ordinary, slightly-confused parent, hers are those of an ordinary, slightly-confused kid. With, unfortunately, super-strength. I’ve always been both intrigued and terrified by the super-powered kid trope, and it’s become harder for me to deal with as a parent myself. Most superpowers, I suspect now, would be simply unsurvivable for bystanders when wielded by someone with the mood management and self-control skills of your average 5-year-old. In some places, parenting could make a difference. In many, that difference would only go so far. As is, unfortunately, the case for Bobbie.

I’m both frustrated and relieved that Daniels leaves the story off where she does. Because nothing good is going to happen, for Bobbie or Rob or anyone else involved, when that door is unlocked.

Because this is an incredibly sweet story—until it isn’t. A story about the redemptive power of loving family—until it isn’t. And then… maybe it’s a story about the arrogance of thinking you can create life and make it come out right. Hubris, scientific or parental—or both. And the hubris of a child, believing she can step safely into the world.

Side note: I first encountered Daniels’s work last week when we shared a virtual reading slot at Arisia, along with Laurence Raphael Brothers and series favorite Sonya Taaffe. Daniels impressed me deeply (and inconveniently) with an excerpt from a work-in-progress narrated by Jenny Greenteeth—sympathetic monster POV is apparently a specialty, and I can’t wait for more.

Next week, we continue our readthrough of The Haunting of Hill House with Chapter 8.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.