I can’t look at the cover of The Eye of the World by Robert Jordan without flashing back to my thirteen-year-old self. I would devour the pages on the bus ride to and from school, tuning out the chatter around me to focus on the stubborn characters from the Two Rivers and their place in the Pattern. And I wasn’t the only one; I spotted other classmates toting the giant books around as well. The Wheel of Time was formative to my understanding of the fantasy genre, and I particularly loved the magic system. At the time, I didn’t see anything problematic about it.

[Spoilers follow for Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series and Iron Widow by Xiran Jay Zhao]

My favourite scene from A Crown of Swords, the seventh book in the series, was when Nynaeve finally learned to channel the One Power without her block; as a wilder, she’d learned to channel by instinct, and even after training at the White Tower, she couldn’t access her powers without being angry. But finally, after seven books of struggling and refusing to “surrender,” because that’s what channeling the female side of the One Power requires, she’s stuck underwater with no way to escape. She has to surrender or die.

And with hope gone, flickering on the edge of consciousness like a guttering candle flame, she did something she had never done before in her life. She surrendered completely.

—A Crown of Swords by Robert Jordan

I liked this scene so much because Nynaeve’s inability to channel “properly” was a puzzle that needed to be solved. There were rules to Robert Jordan’s magic, and she wasn’t playing according to them. She was “cheating,” and as a result, she couldn’t always access her power when she needed to. Overcoming this block felt like a triumph, like positive character development—Nynaeve was always so mad and stubborn, and here she finally learned to give in.

Upon re-reading the series as an adult, this is now my least favourite scene in the entire series.

Buy the Book

The Eye of the World: Book One of The Wheel of Time

Jordan’s magic system is intricate and fascinating. The One Power has two sides—saidar, the female half, which is a gentle river that must be surrendered to or embraced; and saidin, the male half, which is a raging torrent that has to be dominated and controlled. Channelers weave flows of different elements: Earth, Spirit, Water, Air, and Fire. In addition to being more generally powerful than women, men tend to be better at channeling Fire and Earth, while women are better at Water and Air. Females are supposed to be able to compensate for their lower power levels by being more “dexterous” (however, upon re-reading the entire series, I still have no idea what that means, and several women are generally required to take on a single man of greater power).

Women are also able to link their powers—a feat men cannot achieve without them. This doesn’t result in their strength being combined; instead, the leader gets a bonus to their power and the other women in the circle cannot do anything. The main advantage is that the leader can form more complex weaves than they could manage alone. A circle of women can only be expanded beyond thirteen if a male channeler is added. And though a man cannot start a circle, a woman can pass control of a circle over to him once it has been formed.

All of these details add up to one fact: In the Wheel of Time series, gender essentialism is reality. It is built into the fabric of magic itself. Men’s superior strength in the One Power reflects how they are often physically stronger than women. Their need to wrestle saidin into submission, as opposed to women’s surrendering to saidar, reflects a view of men as dominant and powerful, while women are passive and submissive. Interestingly enough, I wouldn’t describe any of the female protagonists using either of those terms. Moiraine, often described as “steel under silk,” is wise, unyielding, and powerful, wielding Fire and Earth to great effect. Egwene, who has a special affinity with Earth, is stubborn and strong, persevering through the harsh training with Aiel Wise Ones and, later, withstanding torture. Elayne is imperious, unyielding, creative in learning how to make ter’angreal—a feat no one of this age had imagined possible—and takes on the weight of princess and, later, queen of Andor. Aviendha is a wildfire. Min is a rock. Cadsuane is a powerhouse.

In fact, if I could offer any critique of Jordan’s main female cast, it’s that they’re too similar—all incredibly stubborn characters with tempers who think men are wool-heads. It’s clear that Jordan does not think that a woman’s place is in the kitchen with a man ordering her around. The yin-yang symbol of the Aes Sedai and the way the One Power spikes when a female and male channeler work together suggests that he thinks men and women are stronger when they join forces, working together as equals. So why does his magic system subscribe to such binary gender norms?

In the scene with Nynaeve, Jordan missed an opportunity to push back against the “rules” of his world that say females need to be submissive. I wish that Nynaeve would have been allowed to wrestle with the One Power like men do. But perhaps he felt the binary nature of the laws he set in place prevented him. Or, more likely, he didn’t think about or recognize the option for a character to break the mold at all.

In the later books, the Dark One reincarnates Balthamel, a male Forsaken, into the body of a female (renamed Aran’gar). Aran’gar still channels saidin, the male half of the One Power. With Aran’gar, Jordan sets a precedent for how a person’s spirit, rather than their body, determines what half of the One Power they use, though this fact is never explored to a further extent with any other characters.

Robert Jordan published the first Wheel of Time book in 1990, and it’s clear he grew up understanding the world from a binary, cis-normative lens, not taking into account the fact that non-binary identities exist and that there are no traits that describe all women and all men. I love the Wheel of Time series, and I respect that Jordan created the fantasy world he wanted, but media doesn’t exist in a vacuum; the very fabric of Jordan’s world reflects gender stereotypes, perpetuating the idea that unequal social systems are natural. Re-reading this series made me wonder what such a binary magic system would look like if written today by an author who understood gender as a spectrum.

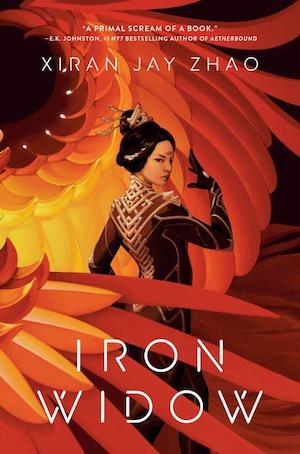

I recently picked up Iron Widow by Xiran Jay Zhao, and my question was answered.

Iron Widow, which was released on September 21, 2021, takes place in a science fantasy world inspired by ancient China. The magic system (or as the author put it in an interview, the “magical-scientific” system), involves giant mechs called Chrysalises, which take the shape of mythical creatures, such as the Nine-Tailed Fox, the Vermilion Bird, and the White Tiger. It draws on the Chinese concept of qi, or life force, and Wuxing, the five elements of wood, fire, earth, metal, and water. Chrysalises require two pilots—a male, who sits in the upper “yang” chair, and a female, who sits in the lower “yin” chair.

Buy the Book

Iron Widow

I was immediately struck by the yin and yang imagery, which also appears in The Wheel of Time (as the emblem of the ancient Aes Sedai, in which the white teardrop shape represents female channelers and the black fang represents male channelers). Yin means “dark” or “moon,” and is associated with femininity. Yang means “light” or “sun” and is associated with masculinity. In ancient Chinese philosophy, yin and yang is a concept that describes how two opposite forces are complementary and connected, working in harmony.

But this concept is twisted in Iron Widow’s Chrysalises. Instead of working together to fight against the Hunduns (alien mechs bent on destroying humanity), the male pilot controls the Chrysalis. He uses the female pilot, also called a concubine, as a source of energy. More often than not, the female pilot dies during a battle, because the male’s mental energy overwhelms her.

To my delight, the story’s protagonist, Wu Zetian, asks the same question that immediately comes to my mind when the workings of the Chrysalises is described:

“What is it about gender that matters so much to the system, anyway? Isn’t piloting entirely a mental thing? So why is it always the girls that have to be sacrificed for power?”

—Wu Zetian, Iron Widow by Xiran Jay Zhao

The novel opens with Zetian noticing a butterfly that has two different wings. Upon researching this phenomenon, she learns that this means the butterfly is both male and female. “Oh, yeah, biological sex has all sorts of variations in nature,” her friend Yizhi tells her, which leads Zetian to question what would happen if a person born like this butterfly piloted a Chrysalis. Which seat would they take? And what would happen if a woman took the upper yang chair or a man took the lower yin chair?

In this world, your “spirit pressure value,” the force with which you’re able to channel your qi, is measurable; when Zetian becomes a pilot, her test results show that her spirit pressure is six hundred and twenty-four, many times greater than most concubine-pilots. Such a high number means she might survive Chrysalis battles alongside a male pilot. She might even be an equal match for one of them, which would elevate her status in this patriarchal society.

Of course, no one knows what to do with Zetian when she not only takes control of the first Chrysalis she pilots, but her qi overpowers the male pilot and kills him.

Unlike Robert Jordan, Xiran Jay Zhao presents gender essentialism—the concept that men and women have specific, innate qualities related to their gender—as a social construct rather than a reality. By choosing ancient China—a society in which women were considered subordinate to men, often physically abused and forced to compete with concubines for their husband’s affections—as her inspiration for the setting, Zhao sets up Zetian to have the odds stacked against her. And that’s what makes the character’s rise to power such a breathtaking story. And while I won’t spoil the reveal, there’s more to the Chrysalises and Zhao’s magic system than meets the eye.

Interestingly, the yin-yang symbols used to represent channelers in the Wheel of Time don’t include the dots that suggest there’s a little bit of yang in yin and vice versa. Women are one thing and men are completely other. Iron Widow, however, embraces this mixture and does away with strict definitions.

“Female. That label has never done anything for me except dictate what I can or cannot do… It’s as if I’ve got a cocoon shriveled too tightly around my whole being. If I had my way, I’d exist like that butterfly, giving onlookers no easy way to bind me with a simple label.”

—Wu Zetian, Iron Widow by Xiran Jay Zhao

I appreciate the evolution that we can see between these two stories: first, a story that was written 30 years ago by a man who likely didn’t intentionally create gender barriers, but drew some hard lines anyway based on the restrictive societal norms he was familiar with; and second, a novel that was written this year by an author who intimately understands how society elevates certain identities for arbitrary reasons. Iron Widow demonstrates the distance we’ve traveled, in the last few decades, in the understanding and depiction of gendered magic systems, and proves that there’s room for all genders and LGBTQ+ identities in our stories. I can’t wait to see more magic systems like Zhao’s in future novels.

Allison Alexander edits sci-fi and fantasy at a small press, writes books, and plays video games the rest of the time. She is the incurable author of Super Sick: Making Peace with Chronic Illness, a geek’s guide to living with a disability. You can find her chasing bokoblins in Hyrule, traipsing with hobbits in Middle-earth, or blogging at aealexander.com.