My new novel, The Final Girl Support Group, comes out on July 13 and it made me think long and hard about murder books. Since we started telling stories, a disproportionate number of them seem to be about killing each other, a trend which got refined to its essence in slasher movies and serial killer books. Murder Books 101 is a place where we can talk about the tics, tropes, and habits of humanity’s favorite literary genre.

Every now and then, a book changes everything. The Exorcist was one example, Jaws was another, and in 1988 it was Silence of the Lambs. Its game-changer status got solidified a few years later when Jonathan Demme’s film adaptation swept the 1991 Academy Awards, taking home the big five (Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actress, Best Actor, Best Adapted Screenplay) and Anthony Hopkins’ Hannibal Lecter became a pop culture icon.

The movie is so familiar that there’s no need to recap it, but let me give a brief description for any newborn infants who might be reading. Silence of the Lambs is about an FBI agent hunting a serial killer with the assistance of another serial killer. The helpful serial killer is played by Anthony Hopkins. The bad serial killer is played by Ted Levine. The helpful serial killer eats his victims and murders numerous police officers over the course of the movie. The bad serial killer skins his victims and doesn’t murder anyone during the movie, however, we can tell he’s bad because he wants to be a woman. During the initial release, the filmmakers waved away criticism from LGBT groups by saying that the bad serial killer wasn’t gay or trans, he was just confused. Everyone seemed to buy it at the time, probably because we’d been conditioned by the fact that for decades the easiest way to spot the serial killer in murder movies was by looking for the character who wore a dress.

In Three On a Meathook (1972) the killer cross-dresses, just like Leatherface does at one point in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Cross-dressing and trans killers appear in Deranged (1974), Relentless 3 (1993), Fatal Games (1984), and Dressed to Kill (1980). The entire climax of Sleepaway Camp consists of the revelation that the killer is trans, a moment that was shocking in 1983 for its Crying Game-style reveal which blew the minds of teenaged boys everywhere.

Murder books are just as bad. In Richard LaPlante’s Steroid Blues, the bodybuilding, bearded man serial murdering the Neo-Nazi, steroid-dealing powerlifters who killed his sister turns out to actually be the sister herself, whose addiction to steroids has turned her into a man. Rockabye Baby (1984) features a serial-killing old man who dresses as a nurse, calls himself “The Bloofer Lady,” and wants to turn into his sister until he gets beaten up by a small child at which point he decides that gender makes him weak and he will now “break the chains of gender” by becoming gender-free. In Dead Man’s Float, the serial killer drowning old people turns out to be a woman who’s actually her own brother.

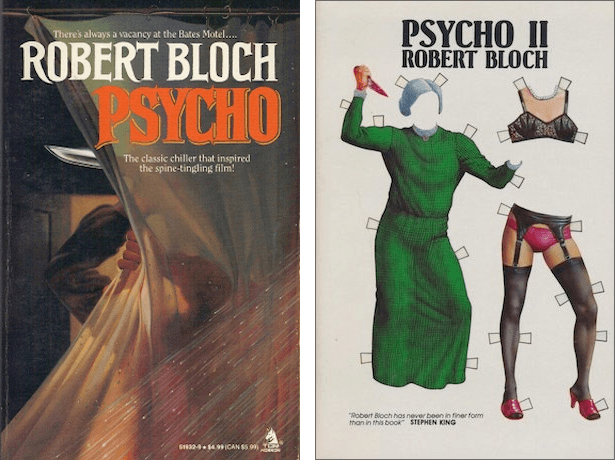

After a while, the second a serial killer appears you start waiting for the inevitable reveal that they want to be a woman. It’s a trope far too pervasive to spring out of nowhere, but where does it come from? Neither transsexuals nor transvestites make the FBI’s profile for serial killers, so it doesn’t reflect reality. Follow this toxic trail back far enough and you inevitably feel like you’ve arrived at Psycho (1960), Alfred Hitchcock’s zeitgeist-changing hit about Norman Bates, a serial killer who dresses as his mother. But behind Hitchcock’s movie is Robert Bloch’s book.

The book and the movie parallel each other closely, with the major difference being that in the book Norman Bates is an obese middle-aged man who’s obsessed with his mother, whereas in the movie it’s handsome young Anthony Perkins who’s obsessed with his mother. Writers are always looking for ways to surprise their readers, and Bloch’s gender shell game is an effective switcheroo. It’s certainly the gimmick that Bloch felt made his book come to life, even going so far in his memoir to write that it’s “Norman” Bates because the character is neither woman “nor man.”

Bloch got the idea for Psycho when he was 41 years old with no money and no prospects and a stalled writing career, trapped in a tiny Wisconsin town. Then Ed Gein happened. A local Wisconsinite, Gein was arrested for murder in 1957 and police discovered his house stuffed with trophies and accessories made from the skin and bones of his victims and multiple bodies he had exhumed from local cemeteries. Gein went down in history as a necrophiliac transvestite who wore women’s skin and kept his mother’s corpse in the basement.

The problem? Ed Gein wasn’t a necrophile, nor was he a transvestite, and he never exhumed his mother’s body.

These ideas seems to have sprung from an 8-page Life pictorial that threw in the line that Gein “wished he were a woman.” The only catch? A psychiatrist hadn’t examined him yet. As the local crime lab director said, “It’s news to me.” Life seemed to have gotten the idea from the Milwaukee Journal which wrote about Gein’s “unnatural attachment” to his mother, quoting an unidentified investigator. They also got an armchair psychiatrist who’d never met Gein to claim that Gein wished “he had been a woman instead of a man” and that he showed symptoms of “acute transvestitism.” The actual psychiatric profile of Gein said nothing about transvestitism or cross-dressing.

All this cross-dressing talk seems to derive from a single polygraph transcript in which the operator, Joe Wilimovsky, suggested to Gein several times that he enjoyed wearing women’s clothing and body parts. “That could be,” Gein cheerfully admitted, and suddenly he was a transvestite who wanted to be a woman. It’s probably a good place to note that Gein was also known to be “highly suggestible” and had trouble telling the difference between things that actually happened and things he was told had happened.

But why did Wilimovsky insert cross-dressing into Gein’s story?

The late 1950s saw America growing increasingly hysterical over crime. The juvenile delinquent was the most terrifying figure in pop culture and the United States Senate had just held hearings about how comic books turned good boys bad. Within months of Gein’s arrest, Charles Starkweather went on a shooting spree in the Midwest for reasons no one could understand, followed by the apparently motiveless In Cold Blood killings; then came the 1960 arrest of Melvin Rees, another serial killer.

Why were men suddenly killing everyone for no good reason? The obvious answer: their mothers.

A psychiatric theory making the rounds in the Forties and Fifties claimed that mothers who showed too much affection for their sons turned them into criminals and sexual deviants. If your mother was close to you, there was a good chance you’d wind up a “sissy.” Philip Wylie’s bestseller Generation of Vipers (1942) laid everything at mom’s feet (while also slamming women’s suffrage), claiming, “Mom’s first gracious presence at the ballot-box was roughly concomitant with the start toward a new all-time low in political scurviness, hoodlumism, gangsterism, labor strife, monopolistic thuggery, moral degeneration, civic corruption, smuggling, bribery, theft, murder, homosexuality, drunkenness, financial depression, chaos and war.”

Buy the Book

The Final Girl Support Group

Robert Moskin wrote a 1958 article in Look called, “The American Male: Why Do Women Dominate Him?” Richard Green published a study called The Sissy Boy Syndrome in 1987 based on research he’d begun back in 1953 trying to identify why some boys grew up to be gay or trans and he laid it squarely at the feet of their mothers: “Unlike fathers, their involvement and investment with sons must be only temperate. It must be finely tuned to provide the son with security and emotional warmth. There must be just enough of mother to round off the hard edges carved by father; she must not smother, stifle, or feminize.”

The psychological profile of the Boston Strangler developed by the police in the early Sixties cast him as “probably homosexual” and his mother as “punitive, overwhelming.” As late as 1980, the DSM claimed “Transsexualism seems always to develop in the context of a disturbed parent-child relationship…Extreme, excessive, and prolonged physical and emotional closeness between the infant and the mother and a relative absence of the father during the earliest years may contribute to the development of this disorder in the male.”

And there you have it. A busted psychiatric theory about how mothers made their sons gay and trans got shoehorned into the case against Ed Gein by eager psychiatrists, and it then made it into Robert Bloch’s novel based on the Gein case, which wound up in Alfred Hitchcock’s hit movie based on Bloch’s book, which flowed out like a poisonous river, leaving its rancid traces on dozens, if not hundreds, of serial killer books and slasher movies.

It’s an idea that persists even today among people who should know better. When you Google Ed Gein, most current articles describe him as a “mama’s boy” who was ruined by his “domineering mother,” a narrative that totally leaves out the fact that, according to Gein himself, his father was an alcoholic nightmare who physically abused Gein and his brother for years. Fun fact: the Boston Strangler also had an alcoholic, abusive father. But why pay attention to that? After all, we all know everything is always mom’s fault.

Grady Hendrix is the award-winning, New York Times bestselling author of The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires, along with a bunch of other books and movies. His new novel is The Final Girl Support Group (out July 13) and you can find more dumb facts about him over at gradyhendrix.com.

Who knew women had such power? The hand that rocks the cradle, huh? Hey, there’s an idea for another movie about motherhood and its beneficial effects. (Oy.)

Nice outline of the poor view of transsexualism and transvestism in our horror fiction, Mr. Hendrix. Can anyone think of any counter-examples?

The Silence of the Lambs example is interesting because Harris seems to have known better- he goes out of his way to tell us that Buffalo Bill isn’t actually transsexual, and even to point out that there is no correlation found between being trans and violence- but none of that sticks quite as much as the image of the scary serial killer man in a dress.

CBS’s Clarice had a trans woman call the main character out, in a somewhat meta moment, for the book’s and movie’s perpetuation of the trope.

Oliver in Elizabeth Hand’s Waking the Moon was a sympathetic transsexual character, one whose transsexuality was important in thwarting the Moon Goddess’s advent.