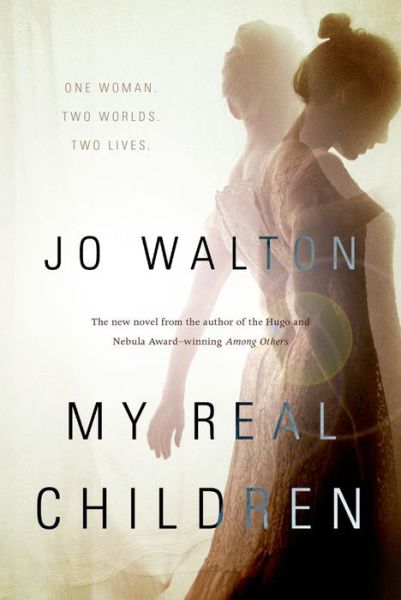

Check out Jo Walton’s My Real Children, available May 20th from Tor Books! Read an excerpt below, and learn more about the cover design here.

It’s 2015, and Patricia Cowan is very old. “Confused today,” read the notes clipped to the end of her bed. She forgets things she should know—what year it is, major events in the lives of her children.

But she remembers things that don’t seem possible. She remembers marrying Mark and having four children. And she remembers not marrying Mark and raising three children with Bee instead. She remembers the bomb that killed President Kennedy in 1963, and she remembers Kennedy in 1964, declining to run again after the nuclear exchange that took out Miami and Kiev.

Her childhood, her years at Oxford during the Second World War—those were solid things. But after that, did she marry Mark or not? Did her friends all call her Trish, or Pat? Had she been a housewife who escaped a terrible marriage after her children were grown, or a successful travel writer with homes in Britain and Italy? And the moon outside her window: does it host a benign research station, or a command post bristling with nuclear missiles?

1

VC: 2015

“Confused today,” they wrote on her notes. “Confused. Less confused. Very confused.” That last was written frequently, sometimes abbreviated by the nurses to just “VC,” which made her smile, as if she were sufficiently confused to be given a medal for it. Her name was on the notes too—just her first name, Patricia, as if in old age she were demoted to childhood, and denied both the dignity of surname and title and the familiarity of the form of her name she preferred. The notes reminded her of a school report with the little boxes and fixed categories into which it was so difficult to express the real complexity of any situation. “Spelling atrocious.” “Needs to pay attention.” “Confused today.” They seemed remote and Olympian and impossible to appeal. “But Miss!” the kids would say in more recent years. She would never have dared when she was in school, and neither would the obedient girls of her first years of teaching. “But Miss!” was a product of their growing confidence, trickle-down feminism, and she welcomed it even as it made her daily work harder. She wanted to say it now herself to the nurses who added to her notes: “But Miss! I’m only a little confused today!”

The notes hung clipped to the end of her bed. They listed her medication, the stuff for her heart she had been taking for years since the first attack. She was grateful that they remembered it for her now, the abrupt Latin syllables. She liked to check the notes from time to time, even though the staff discouraged it if they caught her at it. The notes had the date, which otherwise was hard to remember, and even the day of the week, which she so easily lost track of here, where all days were alike. She could even forget what time of year it was, going out so seldom, which she would have thought impossible. Not knowing the season really was a sign of severe confusion.

Sometimes, especially at first, she looked at the notes to see how confused she appeared to them, but often lately she forgot, and then forgot what she had forgotten to do among the constant morass of things she needed to keep track of and the endless muddle of notes reminding herself of what she had meant to do. She had found a list once that began “Make list.” VC, the attendants would have written if they had seen it; but that was long before the dementia began, when she had been still quite young, although she had not thought so at the time. She had never felt older than those years when the children were small and so demanding of her attention. She had felt it a new lease on youth when they were grown and gone, and the constant drain on her time and caring was relieved. Not that she had ever stopped caring. Even now when she saw their faces, impossibly middle-aged, she felt that same burden of unconditional loving tugging at her, their needs and problems, and her inability to keep them safe and give them what they wanted.

It was when she thought of her children that she was most truly confused. Sometimes she knew with solid certainty that she had four children, and five more stillbirths: nine times giving birth in floods of blood and pain, and of those, four surviving. At other times she knew equally well that she had two children, both born by caesarean section late in her life after she had given up hope. Two children of her body, and another, a stepchild, dearest of them all. When any of them visited she knew them, knew how many of them there were, and the other knowledge felt like a dream. She couldn’t understand how she could be so muddled. If she saw Philip she knew he was one of her three children, yet if she saw Cathy she knew she was one of her four children. She recognized them and felt that mother’s ache. She was not yet as confused as her own mother had been at last when she had not known her, had wept and fled from her and accused her of terrible crimes. She knew that time would come, when her children and grandchildren would be strangers. She had watched her mother’s decline and knew what lay ahead. In her constant struggle to keep track of her glasses and her hearing aid and her book it was this that she dreaded, the day when they came and she did not know them, when she would respond to Sammy politely as to a stranger, or worse, in horror as to an enemy.

She was glad for their sake that they didn’t have to witness it every day, as she had done. She was glad they had found her this nursing home, even if it seemed to shift around her from day to day, abruptly thrusting out new wings or folding up on itself to make a wall where yesterday there had been a corridor. She knew there was a lift, and yet when the nurses told her that was nonsense she took the stairlift as docilely as she could. She remembered her mother struggling and fighting and insisting, and let it go. When the lift was there again she wanted to tell the nurse in triumph that she had been right, but it was a different nurse. And what was more likely, after all—that it was the dementia (“VC”), or that place kept changing? They were gentle and well-meaning, she wasn’t going to ascribe their actions to malice as her mother had so easily ascribed everything. Still, if she was going to forget some things and remember others, why couldn’t she forget the anguish of her mother’s long degeneration and remember where she had put down her hearing aids?

Two of the nurses were taking her down to the podiatrist one day—she was so frail now that she needed one on each side to help her shuffle down the corridor. They stood waiting for the elusive lift, which appeared to be back in existence today. The wall by the lift was painted an institutional green, like many of the schools where she had taught. It was a color nobody chose for their home, but which any committee thought appropriate for a school or a hospital or a nursing home. Hanging on the wall was a reproduction of a painting, a field of poppies. It wasn’t Monet as she had thought on earlier casual glances; it was one of the Second Impressionist school of the Seventies. “Pamela Corey,” she said, remembering.

“No,” the male nurse said, patronizing as ever. “It’s David Hockney. Corey painted the picture of the ruins of Miami we have in the little day room.”

“I taught her,” she said.

“No, did you?” the female nurse asked. “Fancy having taught somebody famous like that, helped somebody become a real artist.”

“I taught her English, not art,” Pat said, as the lift came and they all three went in. “I do remember encouraging her to go on to the Royal Academy.” Pamela Corey had been thin and passionate in the sixth form, and torn between Oxford and painting. She remembered talking to her about safe and unsafe choices, and what one might regret.

“Somebody famous,” the female nurse repeated, breaking her train of thought.

“She wasn’t famous then,” Pat said. “Nobody is. You never know until too late. They’re just people like everyone else. Anyone you know might become famous. Or not. You don’t know which ones will make a difference or if any of them will. You might become famous yourself. You might change the world.”

“Bit late for that now,” the nurse said, laughing that little deprecating laugh that Pat always hated to hear other women use, the laugh that diminished possibilities.

“It’s not too late. You’d be amazed how much I’ve done since I was your age, how much difference I’ve made. You can do whatever you want to, make yourself whatever you want to be.”

The nurse recoiled a little from her vehemence. “Calm down now, Patricia,” the male nurse said on her other side. “You’re scaring poor Nasreen.”

She grimaced. Men always diminished her that way, and what she had been saying had been important. She turned back to the female nurse, but they were out of the lift and in a corridor she’d never seen before, a corridor with heather-twill carpet, and though she had been sure they were going to the podiatrist it was an opthalmologist who was waiting in the sunny little room. Confused, she thought. Confused again, and maybe she really was scaring the nurses. Her mother had scared her. She hated to close herself back in the box of being a good girl, to appease, to smile, to let go of the fierce caring that had been so much a part of who she was. But she didn’t want to terrify people either.

Later, back in her bedroom with a prescription for new reading glasses that the nurse had taken away safely, she tried to remember what she had been thinking about Pamela. Follow your heart, she had said, or perhaps follow your art. Of course Pamela hadn’t been famous then, and there had been nothing to mark her as destined for fame. She’d been just another girl, one of the hundreds or thousands of girls she had taught. Towards the end there had been boys too, after they went comprehensive, but it was the girls she especially remembered. Men had enough already; women were socialized not to put themselves first. She certainly had been. It was women who needed more of a hand making choices.

She had made choices. Thinking about that she felt the strange doubling, the contradictory memories, as if she had two histories that both led her to this point, this nursing home. She was confused, there was no question about that. She had lived a long life. They asked her how old she was and she said she was nearly ninety, because she couldn’t remember whether she was eighty-eight or eighty-nine, and she couldn’t remember if it was 2014 or 2015 either. She kept finding out and it kept slipping away. She was born in 1926, the year of the General Strike; she held on to that. That wasn’t doubled. Her memories of childhood were solitary and fixed, clear and single as slides thrown on a screen. It must have happened later, whatever it was that caused it. At Oxford? After? There were no slides any more. Her grandchildren showed her photographs on their phones. They lived in a different world from the world where she had grown up.

A different world. She considered that for a moment. She had never cared for science fiction, though she had friends who did. She had read a children’s book to the class once, Penelope Farmer’s Charlotte Sometimes, about a girl in boarding school who woke up each day in a different time, forty years behind, changing places with another girl. She remembered they did each other’s homework, which worked well enough except when it came to memorizing poetry. She had been forced to memorize just such reams of poetry by her mother, which had come in handy later. She was never at a loss for a quotation. She had probably been accepted into Oxford on her ability to quote, though of course it was the war, and the lack of young men had made it easier for women.

She had been to Oxford. Her memories there were not confusingly doubled. Tolkien had taught her Old English. She remembered him declaiming Beowulf at nine o’clock on a Monday morning, coming into the room and putting the book down with a bang and turning to them all: “Hwaet!” He hadn’t been famous then, either. It was years before The Lord of the Rings and all the fuss. Later people had been so excited when she told them she had known him. You can never tell who’s going to be famous. And at Oxford, as Margaret Drabble had written, everyone had the excitement of thinking they might be going to be someone famous. She had never imagined that she would be. But she had wondered about her friends, and certainly Mark. Poor Mark.

The indisputable fact was: she was confused. She lost track of her thoughts. She had difficulty remembering things. People told her things and she heard them and reacted and then forgot all about them. She had forgotten that Bethany had been signed by a record label. That she was just as delighted the second time Bethany told her didn’t matter. Bethany had been crushed that she had forgotten. Worse, she had forgotten, unforgivably, that Jamie had been killed. She knew that Cathy was wounded that she could have forgotten, even though she had said that she wished she could forget herself. Cathy was so easily hurt, and she wouldn’t have hurt her for anything, especially after such a loss, but she had, unthinkingly, because her brain wouldn’t hold the memory. How much else had she forgotten and then not even remembered that she had forgotten?

Her brain couldn’t be trusted. Now she imagined that she was living in two different realities, drifting between them; but it must be her brain that was at fault, like a computer with a virus that made some sectors inaccessible and others impossible to write to. That had been Rhodri’s metaphor. Rhodri was one of the few people who would talk to her about her dementia as a problem, a problem with potential fixes and workarounds. She hadn’t seen him for too long. Perhaps he was busy. Or perhaps she had been in the other world, the world where he didn’t exist.

She picked up a book. She had given up on trying to read new books, though it broke her heart. She couldn’t find where she had put them down and she couldn’t remember what she had read so far. She could still re-read old books like old friends, though she knew that too would go; before the end her mother had forgotten how to read. For now, while she could, she read a lot of poetry, a lot of classics. Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford came to her hand now, and she opened it at random to read about Miss Matty and her financial difficulties back in the time of King William. “The last gigot in England had been seen in Cranford, and seen without a smile.”

After a while she let the book drop. It had grown dark outside, and she got up and tottered over to draw the curtains. She made her way carefully, hanging onto the bed and then the wall. They didn’t like her to do it without the quad cane but she was safe enough, there wasn’t room to fall. Though she had fallen once on her way to the toilet and forgotten that she had a button to call for help. The curtains were navy blue, although she was quite sure there had been a pale green blind the last time. She leaned on the window sill, looking out at the bare branches of a sycamore moving in the breeze. The moon was half-obscured by a thin veil of cloud. Where was this place? Up on the moor? Or was it somewhere along the canal? There might be birds in the branches in the morning. She must remember to come and look. She had her binoculars somewhere. She remembered insisting on holding on to them and Philip saying gently that she wouldn’t have any use for them in the nursing home and Jinny saying in her gruff way that she might as well bring them if she wanted them. They must be here somewhere, unless that was in the other world. It would be very unfair if the binoculars were in one world and the tree were in the other.

If there were two worlds.

If there were two worlds, then what caused her to slide between them? They weren’t two times as they were for Charlotte. It was the same year, whichever year it was. It was just that things were different, things that shouldn’t have been different. She had four children, or three. There was a lift in the nursing home, or there was only a stairlift. She could remember things that couldn’t simultaneously be true. She remembered Kennedy being assassinated and she remembered him declining to run again after the Cuban missile exchange. They couldn’t both have happened, yet she remembered them both happening. Had she made a choice that could have gone two ways and thereafter had two lives? Two lives that both began in Twickenham in 1926 and both ended here in this nursing home in 2014 or 2015, whichever it was?

She shuffled back and looked at her notes, clipped to the end of the bed. It was February 5th 2015, and she was VC. That was definite, and good to know. She sat down but did not take up the book. It would be suppertime soon, she could hear the trolley moving down the corridor. They’d feed her and then it would be time for bed. This was the same whatever world she was in.

If she had made a choice—well, she knew she had. She could remember as clearly as she could remember anything. She had been in that little phone box in the corridor in The Pines and Mark had said that if she was going to marry him it would have to be now or never. And she had been startled and confused and had stood there in the smell of chalk and disinfectant and girls, and hesitated, and made the decision that changed everything in her life.

2

Adam: 1933

It was July 1933 and Patsy Cowan was seven years old and they were in Weymouth for two glorious weeks. There was a band in the bandstand, and sculptures of animals made of sand, and donkeys to ride and the sea to swim in, and they were building a sand pulpit for Mr. Price to preach from in the evening. She was wearing a brown cotton bathing suit, though most of the younger children and some of the other seven-year-olds still went bare. She could remember running bare when she had been a mere child, but she liked the bathing suit. Her fine brown hair was tied into bunches on both sides of her head, and when she shook her head hard she could make them slap her cheeks. She didn’t do it though, because Oswald said it made her look stupid, shaking her head for nothing. Oswald was just ten, she envied his summer birthdays. He wore long striped swimming shorts, down to his knees, and he was beginning to tan already.

They had come down by the late train on Friday night and today was Sunday, only the second whole day of the holiday, with twelve more whole days to go. They wouldn’t all twelve be this glorious, Patsy knew that. The sun couldn’t shine all day every day even on holiday, there was bound to be at least one rainy day. But on a rainy day Dad would take them to the museum or to an interesting old church or castle, which might not be as wonderful as a day on the beach but it was still fun. There would also be one afternoon when Dad would take Oswald to see football—“Sorry old girl, this is a boys’ afternoon out, just us men!” Dad would say, as he said every year. It did no good to argue that she loved football, or that if Oswald was going to have Dad to himself for an afternoon she should have the same. Dad had pointed out last year that she was having an afternoon with just Mum, and of course even then when she’d been only six she had known better than to complain.

They dug the pulpit with spades and with their hands. The spades had wooden handles and metal blades, and they were just like real spades except for the size. Hers was red and Oswald’s was blue, and Mum said that if they lost them they needn’t think they were getting any more. Mum was sitting reading on a deck chair she had paid for at the top of the beach, but Dad was right there with them, organizing all the church children building the pulpit. Patsy loved the feeling of sand between her toes and the way sand was so easily shaped and manipulated. She loved making a mark and rubbing it out. Sand was hot on top and cool underneath when you dug, and it was clean, it brushed off, or if it didn’t you could easily wash it off if you went down to bathe. Sand wasn’t like dirt at home. You could get as sandy as you liked and just run into the water and be all clean again.

Best of all was coming down to the beach early in the morning when the tide had washed away all the marks of the day before, and running on the hard-packed sand making footprints. The first morning Dad had brought them down, they had followed the tracks of a man and a dog, the little paw prints running in and out of the edge of the sea, until at last they caught up with them and saw that the dog was a white and black terrier and the man was just a man who said “Good morning” politely to Dad. But this morning coming down before church they had been the very first, and they had run across the great flat sand in the early morning light, “the lone and level sands stretch far away” as it said in the poem, with the waves lapping with little white edges and beyond them the sea stretching out even further away, stretching all the way to America. Dad walked along the edge of the sea looking for shells and seaweed, but the children ran barefoot and free. Patsy could run as fast as Oswald, even though he was two and a half years older. She could run faster than any of the other seven-year-olds. One day later in the week Dad would organize athletics on the beach, he had promised, and she would win, she knew she would. She could do a handstand every time and a cartwheel twice out of three times.

“This is going to be the best pulpit ever!” she said, digging enthusiastically. “Better than last year. And Mr. Price will give the best sermon ever and convert all the heathens!”

“That’s right, old girl,” Dad said. “But don’t throw your sand out behind you without looking, you’re getting it on people.”

She looked around guiltily, but he was laughing, not angry, although her sand had spattered his legs. It was so nice to spend whole days with Dad like this. It only ever happened in the summer and perhaps for a day or two at Christmas. He worked so hard selling wirelesses and mending them for people. He went off on his bike before she was up in the morning and sometimes didn’t come back until after she was in bed. On Sundays he didn’t work, but he was usually so tired that Mum made her and Oswald tiptoe around after they came back from church. Sometimes he would rouse himself in the afternoon and take them out for a walk, or organize a ball game in the park. Then she would catch a glimpse of her summer father, the man who loved to play. He had the older children running down to the sea now with buckets, to bring water to wet the sand to shape it. Patsy dug more carefully.

“Why aren’t you a minister, Dad, like Mr. Price?” she asked.

“God didn’t call me that way,” he replied, talking to her the way she liked, as if she were an equal.

“And He did call you to be a wireless installer?”

“Well, I learned about radio in the war, and so when I was demobbed it seemed like a good choice,” he said.

That didn’t seem as grand as God calling him.“Didn’t God—” she began.

“Why do you want me to be a minister anyway, Miss Patsy?” Dad interrupted.

“Ministers only work on Sundays,” she said. “You’d be home with us the rest of the time.”

For a moment she was afraid from the look on Dad’s face that she’d said something naughty, or worse, blasphemous. Her mother shut her in the cupboard when she said anything blasphemous, though she never meant to. She knew thoughts about God and ministers had the potential to get to dangerous places. Then he threw back his head and laughed so much that all the other children laughed too, even though they hadn’t been listening and didn’t know what he was laughing about, and other groups on the beach, people they didn’t know at all, turned their heads and looked at them. Patsy hadn’t meant to be funny, but she was so relieved she had been funny by mistake and not blasphemous by mistake that she laughed too, but hers wasn’t a real laugh or the infectious hilarity of the other children.

“I must tell Mum that,” Dad said. “How she’ll laugh! I dare say she’d not like it if I was under her feet six days a week instead of only one!”

Oswald was back with a bucket almost full of sea water. He must have been carrying it very carefully so as to avoid spilling. “Tell Mum what?” he asked.

“Patsy wants me to be a minister so I’ll only have to work on Sundays!”

Oswald didn’t laugh. “I’m not sure Mum would find that funny,” he said.

“No, maybe you’re right,” Dad agreed.

“Patsy’s not a baby any more. She should know that ministers work hard visiting the sick and… writing their sermons and…” it was clear that Oswald’s imagination was at an end.

Dad laughed again. “It’s all right old boy. I won’t say anything to Mum. You’re probably right that she wouldn’t see the funny side.”

“It’s just that she wants us to be like Lady Leverside’s children,” Oswald said.

Dad pulled Patsy onto his lap and patted the sand for Oswald to sit next to him, which he did, setting down the heavy bucket. “She wants the best for you,” he said. “For both of you. That’s why she wants you to dress nicely and speak properly and all of that. Your Mum worked for Lady Leverside before we were married, and that’s where she learned to take care of children. So that’s how she knows how to make bathing costumes and recite poetry and all that. I didn’t have the advantages you’re getting. Your Gran didn’t know any of the things you’re having the chance to learn from your Mum.”

Patsy smiled at the thought of comfortable old Gran reciting poetry. Gran cooked on the fire and made the best toffee in the world, but she wasn’t a poetry sort of person somehow.

“But, while it’s good that you have those advantages, this is very important, I want you to know that you’re just as good as Lord Leverside’s children, as good as any children in the world. You can do as much as they can, more. You can do better than them. You can go far and achieve great things.”

“But they’re honourable children,” Patsy said. “The Honourable Letitia and the Honourable Ralph. We’re not like them. Mum says we’re not.”

“She says she doesn’t want us to be common,” Oswald said.

“Like when you were playing football with the boys and you came home and said—” Patsy started eagerly, but Oswald punched her arm.

“It’s not fair repeating tales,” he said.

Dad looked at him reproachfully. “It’s better than hitting a girl, and one three years younger than you. That’s just the kind of thing I’m talking about, where you have the chance to learn better and you should take it.”

“Sorry,” Oswald said. “But honestly, Dad, she shouldn’t repeat things like that.”

“No, Patsy, your brother is right. If he said something he shouldn’t and Mum punished him, then that should be the end of it.”

“Sorry,” Patsy said. “I didn’t mean to sneak.” She put out her hand to Oswald to shake, which he did.

“But coming back to the other thing,” Dad said, “The fact that they’re The Honourable and you’re just Master and Miss means nothing. You’re every bit as good as they are, and you can go as far as they can. When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?”

“Adam!” Patsy said, quickly before Oswald could answer such an easy riddle. “And Eve was the lady!”

Oswald laughed. “She doesn’t understand, Dad.”

“But you do, don’t you? You know what I’m saying. Look at it this way, did Lady Leverside bring up her children herself? No, she chose your mother to do it. You’re having the same upbringing they had.”

One of the other children came to ask Dad a question about the pulpit and he got up to help. Patsy sat still, crinkling her toes and feeling the sand scrunch up under them. Lady Leverside’s children had seemed as far above her as the sun and the moon. Mum never said Patsy was better than they were at anything, never even as good. It was always “The Honourable Letitia would never have spoken with her mouth open…” or “forgotten her cushion…” or “come downstairs with her hair unbrushed.” Patsy was used to thinking of them as paragons. She considered Dad’s view that she was as good as they were, and potentially even better. Yet she knew they had six of everything, all of the best, and if they grew out of any of their clothes they had more right away, ordered from John Lewis’s. She and Oswald only had one set of best clothes at a time, and only two other sets of clothes, and they were forever outgrowing them or tearing them. She tore hers climbing trees and Oswald tore his playing football or fighting with boys.

“When I’m thirteen they’re going to send me away to school,” Oswald said, plopping down on the sand beside her.

“Will they me?” Patsy was alarmed, even though thirteen seemed impossibly far away, almost the whole length of her lifetime.

“I don’t think so, because it’s really expensive and you’re a girl,” Oswald said. He wasn’t looking at her, he was tracing a complicated design in the sand with his finger. “I think they’ll send you to a day school.”

“Why will they send you then?”

“Because of what Dad just said about getting on. Dad left school when he was fourteen and he’s been sorry ever since. He wants me to be a gentleman, just the same as Mum does.” He didn’t look up, but he piled up the sand wildly over the pattern he had made.

“Like Adam,” Patsy said, and for the second time didn’t understand why she had made somebody laugh.

“But it’s all such tosh,” Oswald said. “I’d a hundred times rather be brought up by Gran and get a job at fourteen than spend my life trying to ape something I’m not.”

“Why don’t you tell them so, then?”

“Oh come on Pats, you know there are things you can say and things you can’t.”

She did know. It seemed she had always known. She wanted to do something to comfort her brother, but there wasn’t anything. Gran would have hugged him, but in their house hugging was discouraged. She put her hand out again for him to shake, and he shook it solemnly.

“Come on,” he said.

“Where?” she asked, getting up at once expectantly.

“You’d come anywhere with me, wouldn’t you, Pats?” Oswald smiled down at her. “I must go down to the sea again!”

“The lonely sea and the sky!” she shouted.

“Anything less lonely than the sea in Weymouth on a hot Sunday morning in July is difficult to imagine,” Dad said.

Later, after a bathe where she had swum ten strokes without Dad holding on, she ran on rubbery legs up to Mum’s deckchair. Mum was reading the paper and looking very serious, but she put it down when she saw them and got out the towels and their clothes so they could dress nicely for lunch. Mum had sewn brightly striped beach towels into little tents with elastic around their necks so that they could take their wet things off underneath and didn’t have to go into the changing huts, which were smelly and besides cost money.

Dad dried his back with a big flat towel. “Patsy’s really learning to swim,” he said. “You should enroll her for lessons at the baths when we get back to Twickenham. It’s easier to swim in the baths,” he said over his shoulder to her. “There aren’t any waves to smack you in the face.”

“All right,” Mum said. “If she’d like it. Oswald started going when he was about this age.”

“Have you had a nice peaceful morning?”

“Lovely,” Mum said, though how it could be lovely sitting still in a deckchair reading Patsy couldn’t imagine.

“Is there any news in the paper?” Dad asked.

Mum tutted, which she did when she was going to report on something of which she disapproved. “It seems as if the Nazis in Germany have banned all the other political parties— made them illegal just like that. Theirs is the only party. Goodness knows how they think that’s going to work when they have elections.”

“I don’t suppose they’re planning to have elections,” Dad said. “It looks to me as if that Herr Hitler intends to be Führer for life.”

“And such horrible things,” Mum said. Then she changed her tone completely and turned to Patsy. “Aren’t you dry yet? They’ll be laying out our lunch before we get back if you don’t hurry. We don’t want to make extra work for Mrs. Bonestell.”

Oswald pulled off his towel, revealing his neat shirt and shorts underneath. “I wish we could have a picnic on the beach.”

“Not on a Sunday,” Mum said, reprovingly.

“We got the pulpit built,” Dad said quickly. “Mr. Price will be able to get right up there and preach, and we can all sing hymns as loudly as we can. Patsy was saying he’d convert any heathen on the beach.”

“I hope you built it in the right place this time,” Mum said.

“We took proper notice of the tide,” Dad said. “Don’t worry, there won’t be any of that King Canute preaching this year. Are you dressed under there yet, Patsy?”

Patsy had got her dress twisted up somehow so she couldn’t find the hole for her right arm. Dad held the big towel up and Mum rapidly sorted her out. “Now let’s go up and get some Sunday dinner,” Dad said. “Lunch, I mean. Come on!”

Twelve and a half more days of holiday, Patsy thought, and swimming lessons when she got home. Even if Oswald did have to go away to school it wasn’t for three years, and even if the Germans were acting peculiar they were a long way away. Mum and Dad were smiling at each other and Oswald was carrying the bucket and both spades, and if they were lucky there might be tinned salmon and tomatoes for lunch.

My Real Children © Jo Walton, 2014