Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories.

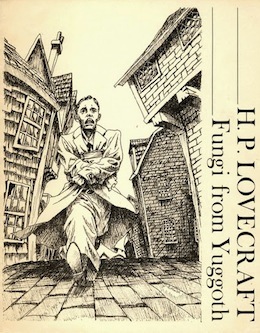

Today we’re looking at the final 12 sonnets in the “Fungi From Yuggoth” sonnet cycle, all written over the 1929-30 winter break (December 27 to January 4, and don’t you feel unproductive now?). They were published individually in various magazines over the next few years, and first appeared together in Arkham House’s Beyond the Wall of Sleep collection in 1943.

Spoilers ahead.

I cannot tell why some things hold for me

A sense of unplumbed marvels to befall,

Or of a rift in the horizon’s wall

Opening to worlds where only gods can be.

Summary

- St. Toad’s: Narrator explores the ancient labyrinth of mad lanes that lies south of the river. No guide-book covers its attractions, but three old men shriek a warning to avoid St. Toad’s cracked chimes. He flees at their third cry, only to see Saint Toad’s black spire ahead.

- The Familiars: John Whateley’s neighbors think him slow-witted for letting his farm run down while he studies queer books he found in his attic. When he starts howling at night, they set out to take him to the Aylesbury “town farm.” However, they retreat when they find him talking to two crouching things that fly off on great black wings.

- The Elder Pharos: Men say, though they haven’t been there, that Leng holds a lighthouse or beacon that beams blue light at dusk. In its stone tower lives the last Elder One, masked in yellow silk. The mask supposedly covers a face not of earth; what men found who sought the light long ago, none will ever know.

- Expectancy: Narrator senses unplumbed yet half-recalled worlds of wonder beyond such mundane things as sunsets, spires, villages and woods, winds and sea, half-heard songs and moonlight. Their lure makes life worth living, but no one ever guesses what they hint at.

- Nostalgia: Every autumn birds fly out to sea, chattering in a joyous haste to find a land their inner memories know. They search for its terraced gardens and temple-groves (and luscious mangoes) but find only empty ocean. Alas, the towers they seek are sunken deep and given over to alien polyps, but those towers too miss the birds and their remembered song.

- Background: Narrator can’t relate to raw new things because he first saw light in an old town. Harbor and huddled roofs, sunset on carved doorways and fanlights, Georgian steeples with gilded vanes, were the sights of his childhood dreams; they are treasures that cut the trammels of the present and let narrator stand before eternity.

- The Dweller: Explorers dig into a mound and find ruins old when Babylon was young. Within they find statues of fantastic beings beyond the ken of man. Stone steps lead down to a choked gate, which they clear. However, the sound of clumping feet below makes them flee.

- Alienation: A man dreams each night of remote worlds. He survives Yaddith sane and returns even from the Ghooric zone, but one night he hears across curved space the piping of the voids. The next day he wakes older and changed. The mundane world seems a phantom, and his family and friends are an alien throng to which he struggles to belong.

- Harbour Whistles: Over a town of decaying spires, the ships in harbor send a nightly chorus of whistles. Some obscure force fuses these into one drone of cosmic significance. Always in this chorus we catch notes from no earthly ship.

- Recapture: Narrator follows a path down a dark heath studded with mossy boulders. Cold drops spray from unseen gulfs, but there’s no wind, no sound, no view until he comes to a vast mound scaled by lava steps too big for human use. He shrieks, realizing that some primal star has sucked him here, once more, from man’s dream-transient sphere.

- Evening Star: Narrator watches the rise of the evening star from woods at the edge of a meadow. In the hushed solitude, it traces visions on the air, half-memories of towers and gardens and seas and skies from another life. He can’t tell where this life was, but the star’s rays surely call to him from his far, lost home.

- Continuity: Narrator senses in certain ancient things a dim essence that links them to all laws of time and space—a veiled sign of continuities, of locked dimensions out of reach except for hidden keys. Old farms against hills, viewed by slanting sunlight, move him most and make him feel he’s not far from some fixed mass whose sides the ages are.

What’s Cyclopean: “Ecstasy-fraught” is pretty good. Not sure about “rank-grassed.” Is the grass lined up in ranks? Is the grass stinky?

The Degenerate Dutch: All these newfangled communities are “flimsier wraiths

That flit with shifting ways and muddled faiths.” We all know what that means!

Mythos Making: The blue light shining over Leng! The High Priest Not to Be Named, chatting with Chaos! Anyone else want to listen in?

Libronomicon: John Whateley has “queer books.” Not the kind you’re thinking of, sorry.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Seriously, don’t go following the sound of cosmic piping. No, not even if you’ve come back safely from the Ghooric zone. DON’T DO IT.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

There are advantages to storytelling in a constrained form. One big plus is that you can’t explain everything, or even dwell on it at length. No monologuing final reveals, here, and no hysterical ranting even when shoggoths rear their appendages. What’s the Ghooric Zone? Of what is Saint Toad the patron? You won’t find the answers here, and so the sandbox expands.

Howard’s sandbox may be the most flexible and open-ended shared universe in genre. No copyright constrains the elder gods; no central cast of characters need be referenced. You can tell the original stories from a different angle, build out to either side, use places and characters and concepts in entirely new ways—or just come up with ideas that fit the mood and the setting like non-Euclidean tinker toys. I spend a lot of time, in these posts, talking about the power of Lovecraft’s original work and about his deep flaws as a writer and a person—here’s one place where he exceeded other “men of his time” and indeed of ours. The generosity of the Mythos, the explicit open invitation to contribute within his own lifetime, opened a door so wide that no power can slam it shut.

As with any good cosmic portal, things surge through that would terrify and confound the man foolish enough to give them the opening: because Lovecraft welcomed his friends and students to play with what he made, those he considered eldritch abominations can do the same. Engage him, argue with every one of his founding assumptions, prove him wrong a thousand times—it would have scared the hell out of him, but it makes the Mythos itself larger and stronger and more interesting. We should all be fortunate enough—and generous enough—to create something with such potential to transcend our faults.

Getting back to the sonnets (I was talking about sonnets), we see hints the late-growing nuance around Lovecraft’s own attitudes. With rants and explanations stripped away, it’s more apparent that the narrator of the poems isn’t so sure whether he’s an “us” or a “them.” Or maybe he is sure—the comforting glow of old New England towns is a door to eternity, and the rays of the evening star call from his far, lost home. “You’re not from around here, are you?” The terror of Yuggoth, of Y’hanthlei and the Archives, is that Lovecraft and his protagonists want to think of them as the abodes of alien abomination and incomprehensible monstrosity—but comprehension is all too clear as soon as they finish wading through a certain river in Egypt. They’re home. And the sonnets, for all that one could beg more detail on their intriguing hints, give no room to deny it. No matter how much our semi-autobiographical narrator protests to the contrary, the answer is “no.” He’s not from around here, after all.

That tension is enough to hold a sandbox together, down through aeons.

Saint Toad, according to Robert Anton Wilson, is a byname of Tsathoggua, patron of petrifying fear and creepy mummies. And Richard Lupoff says that the Ghooric Zone, far beyond the orbit of Pluto, is the true location of Yuggoth. Planet Nine, anyone? The nice thing about an open sandbox is that eventually, all questions will be answered. Ideally with horrific, mind-bending knowledge that you will forever regret seeking.

Anne’s Commentary

In this group of twelve sonnets, Lovecraft has nearly surrendered to the rhyme scheme variation abbacddc effegg. Last week, commenter SchuylerH noted that the 16th century poets Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, also wrote sonnets with a similar scheme. One wonders how they found the time, negotiating the touchy politics of Henry VIII’s court, but hey, no TV or Internet in those days to while away the long hours between breakfast and the executioner’s shadow.

Nevertheless, I will privately dub abbacddc effegg the Lovecraftian sonnet. There are nine of them in our last batch of Fungi! There are also two Italianate variations even closer to Wyatt’s: abbaabba cddcee. I’m tempted to think that when Lovecraft could find enough rhymes for that abbaabba octave, he showed off a little. Otherwise an abbacddc octave was more conducive to the unstrained English diction he was trying for in this cycle.

Here at the end of our sonnetic journey, I still don’t see a strong through-line or overarching arc to Fungi from Yuggoth. Their common feature is their subgenre: weird (Lovecraftian!) fantasy. Apart from the opening three sonnets and those featuring the daemon who’s probably Nyarlathotep, I don’t see continuity of plot. However, reading the last twelve poems, I do begin to notice thematic or structural groups or categories.

There are “story” sonnets, like the shortest of short-shorts. Here they include “St. Toad’s,” “The Familiars,” “The Dweller,” and “Recapture.” Story sonnets dominate earlier in the cycle, with the “Book” triad and such outstanding snippets as “The Lamp,” “Zaman’s Hill,” “The Courtyard,” “The Well,” “The Pigeon Flyers,” “The Howler,” and “The Window.”

There are “lore” sonnets, which don’t so much tell a discreet story as relate a bit of Lovecraft’s mythology. Here they’re represented by “The Elder Pharos,” “Nostalgia,” and “Harbour Whistles,” Earlier lore sonnets include “Antarktos,” “The Night-Gaunts,” “Nyarlathotep” and “Azathoth” (thought the last two could also overlap into the story category.)

The closing sequence of Fungi is marked by a third kind of sonnet, which I call the “musing and/or autobiographical” category: “Expectancy,” “Background,” possibly “Alienation,” “Evening Star,” and “Continuity.” Here the narrative voice rings in my inner ear as Lovecraft’s own voice, as he struggles to explicate a weird-Platonic sense of the cosmos. Mundane things are transient dreams—momentary expressions of eternal forms, linked to all the other momentary expressions of eternal forms though we remember the links only dimly. You know, that “fixt mass whose sides the ages are,” that’s the ultimate form or truth. Or else, or at the same time, Azathoth is the ultimate form or truth. And for Lovecraft, the truth’s embodied in, um, Providence and farm houses. Deep, man. Deeper than Y’ha-nthlei or the Vaults of Zin.

I have a feeling one could plumb much from the “musing” poems, if one was in the plumbing mood. I have to admit, I’m more in the “story” mindset at the moment and so most enjoyed the “story/lore” poems in this set of twelve. “St. Toad’s” would make a delicious fiction challenge: Take this in media res snippet, add beginning and development and end, and let’s have a cozy evening reading all our efforts by the fire. I bet a good anthology could come from the exercise!

“The Familiars” goes into the “homely” subcategory of Fungi, where “home” is the Dunwich region. Its companions are “The Well,” “Zaman’s Hill,” and “The Howler.” Of all the sonnets, these four really fulfill Lovecraft’s purpose of writing poetry that’s straightforward and of the vernacular. These are tales told on the general store porch, within the circle of rockers and in hushed tones, lest outsiders hear.

“Alienation” could, as opined above, be musing, or it could be a fairly discreet story, perhaps linkable to “Recapture”—when the “he” of “Alienation” answered the piping from beyond, maybe it led him (now “I”) to the landscape and revelation of “Recapture.” At any rate, we all know where void-born piping comes from. The big A, that’s right. He of the smacked head and final mindless judgment over all.

Fungi, I feel I’ve barely scraped your phosphorescent surfaces. But you’ll continue to sporulate in my mind, and who knows what will come of it? Not anything in a yellow silk mask, I hope.

Next week, by request, we read “Medusa’s Coil”—Lovecraft and Zealia Bishop’s deeply bigoted collaboration—so you don’t have to. Note: starting next week, the Lovecraft reread will be published Wednesday mornings. See you then!

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint in Spring 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.