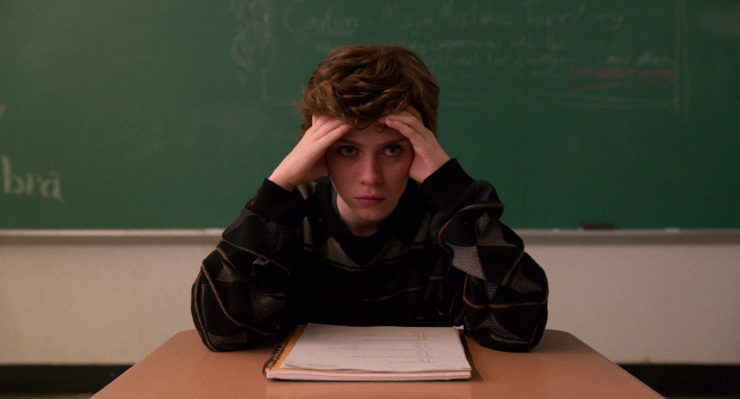

The new Netflix series I Am Not Okay With This is more than okay with revealing, even reveling in, its influences. The story of misfit Sydney (Sophia Lillis of It and Gretel & Hansel) navigating the high school social order carries the DNA of John Hughes films of the 1980s, complete with a detention episode reminiscent of The Breakfast Club. On the other hand, Sydney’s telekinetic superpowers bring to mind decades of X-Men comic books and, in one explosive sequence, the David Cronenberg classic Scanners.

But I Am Not Okay With This acknowledges its most important cinematic influence with its opening image, a climactic moment from which the series flashes back and builds toward over its eight-episode season: Sydney walking away from a disastrous high school dance, her dress covered in blood.

The scene clearly echoes the iconic climactic moment of Carrie, the 1974 Stephen King novel that was adapted into the 1976 blockbuster directed by Brian De Palma. But despite these unsubtle nods, series creators Jonathan Entwhistle and Christy Hall are not simply ripping off King and De Palma—rather, they’re using I Am Not Okay With This to re-examine Carrie’s themes through a 21st-century lens.

As both King’s first published novel and the first of his works to be adapted for the screen, Carrie looms large in the public consciousness. The story of a timid (and telekinetic) teenager (Sissy Spacek, in an Oscar-nominated performance) sheltered and dominated by her religious zealot mother Margaret (fellow Oscar nominee Piper Laurie), Carrie is a powerful critique of the pressures foisted upon teen girls in the 1970s. The story opens with the title character experiencing her first period in a gym shower. Unaware of what’s happening, she screams in terror and begs her classmates for help. Dumbfounded by her extreme response, the other girls mock Carrie until she’s rescued by gym teacher Miss Collins (Betty Buckley).

Buy the Book

Flyaway

Miss Collins’s rebuke stirs remorse in classmate Sue Snell (Amy Irving), who tries to make amends by asking her boyfriend Tommy Ross (William Katt) to take Carrie to the prom. But mean girl Chris Hargensen (Nancy Allen) rejects Miss Collins’s call for empathy and instead plots to embarrass Carrie. Working with her boyfriend Billy Nolan (John Travolta), Chris rigs the vote to make Carrie the homecoming queen, then drenches her in pig blood in front of the entire school.

The prank leaves Carrie soaked with blood and catatonic with rage. She unleashes her full powers on the crowd, killing everyone except Sue. Upon returning home, she’s attacked by her mother, resulting in a fight that leaves both women dead. The film ends with a legendary jump scare, in which Sue visits Carrie’s grave only to be grabbed by a bloody hand exploding out of the dirt.

Not only did Carrie set the stage for the King novels and adaptations that dominated the 1980s, but it also set the standard for outcast teen narratives that would be revisited at least every decade or so. In 1999, The Rage: Carrie 2 director Katt Shea and writer Rafael Moreau used the story of Carrie’s heretofore unseen half-sister to explore ideas about rape and bullying in the late ‘90s. A 2002 TV remake from director Dave Carson and Hannibal showrunner Bryan Fuller not only provided a more sympathetic take, in which both Carrie and Sue survive the “black prom” to start a new life together, but also delves into the adults’ culpability for shaping the teens who harass and torment Carrie. The 2013 remake directed by Kimberly Pierce and written by Riverdale showrunner Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa puts Chloe Grace Moretz in the title role and introduces a cyberbullying angle. Here, Chris (Portia Doubelday) and her friends record Carrie’s locker-room freak-out and put it on YouTube, working it into the climactic prom prank.

Series creators Entwistle and Hall intentionally place I Am Not Okay With This within the long line of Carrie stories by invoking the original’s most iconic image. But even as we watch Lillis storm down the street in a blood-soaked dress, her first lines distinguish the show from its predecessors: “Dear Diary… go fuck yourself.” Sydney may hold a telekinetic teen ostracized by her classmates and harangued by her single mother, but she is no demurring Carrie White.

This attitude is only one of the ways that the series reimagines Carrie’s themes for a contemporary audience. A classroom sequence in the premiere episode may seem familiar to some, in which jocks Brad (Richard Ellis) and Ricky (Zachary S. Williams) interrupt a sex-ed lecture with an obvious dirty joke. But where the reference would have eluded the sheltered Carrie and would be further grounds for bullying by her female classmates, here the guys demand she “laugh” because Brad’s joke was “funny.” Where even Chris Hargensen recognized her mistreatment of Carrie as bullying (though she sees it as a justified attack, given their different social classes), Brad and Ricky consider Sydney the aggressor: By not smiling when they expect a smile, she’s violating a social code that they want to reinforced.

Moments like these recur throughout the series, establishing Sydney as a character who isn’t sheltered but is rather all too aware of the way that the world works. Sydney wants nothing more than to sink into anonymity and live the “normal teenage” life, but cannot, because no such thing exists. As she puts it in her introductory voice-over, “I am not special…and I’m okay with that.”

But she cannot be normal. Her father recently committed suicide, leaving her with not only an overburdened mother (Kathleen Rose Perkins) to help and a younger brother (Aidan Wojtak-Hissong) to care for, but also a mind buzzing with unresolvable emotions. Sydney’s angry outbursts draw the attention of school counselor Ms. Cappriotti (Patricia Scanlon), who plays the Miss Collins-esque role of protector. But where Miss Collins urged Carrie to go to prom like every other teenager (with disastrous results), Ms. Cappriotti aids Sydney by giving her a diary to fill with “normal teenager” stuff. The fact that Ms. Cappriotti points to no model for Sydney to emulate, and instead gives her blank pages to fill with her own thoughts, underscores the point Syd is slowly learning: there is no normal. Her uniqueness is exactly what makes her “not special,” because everyone is unique.

This key understanding that we’re all weirdos, whether or not we can move things with our minds, drives the ethos of I Am Not Okay With This. Where De Palma famously made an overheated spectacle of King’s novel, filling it with dizzying camera moves and allowing Piper to give a performance pitched toward black comedy, Entwhistle and Hall prefer to cultivate a drier, more ironic tone. Needle-drops sometimes declare too obviously a scene’s intended emotions and Sydney’s diary entries pop up via often intrusive voice-over, but there’s a playfulness to the proceedings that ground the characters in relatable human emotions.

That’s particularly true of Sydney’s two closest friends, popular kid Dina (Sofia Bryant) and quirky neighbor Stanley Barber (Lillis’s It co-star Wyatt Oleff). Even as she maintains a real bond with both of these friends, Sydney recognizes her difference from them. She considers her friendship with Dina to be some type of cosmic mistake, a fluke that put a popular and pretty girl together with the weirdo—a feeling only intensified when Dina begins dating the aforementioned jock, Brad.

Conversely, Sydney initially resists friendship overtures from Stanley, despite admiring his apparent disregard for social standards. She pursues a relationship with Stanely after deciding that she, like Dina, needs a boyfriend. But even as she realizes that she is attracted to Dina and not Stanley, she still appreciates the support he gives her.

Stanley becomes Sydney’s confident, a friend unfazed by her weirdness who offers encouragement when he learns about her powers. The series’ most affecting scene is an interaction between Sydney and Stanley at the end of the second episode. When a simple game of “Would You Rather…?” presents Sydney with the opportunity to talk about her abilities, she instead confesses that she has pimples on her thigh. After chuckling for a minute, Oleff spreads a giant grin across his face and declares, “I got you beat.” Stanley turns around and removes his shirt to reveal a back riddled with acne. Sydney responds by standing up, dropping her pants, and showing him the pimples on her thighs.

Throughout the interaction, both characters acknowledge that they are disgusted by the other’s blemishes. But they never reject one another for it. Instead, they celebrate the weirdness and form a bond over their shared deviations.

Sydney’s boasting of a body changed by puberty is a far cry from Carrie White screaming in the shower. Stan’s gleeful acceptance is the exact opposite of Chris Hargensen’s cruel teasing, as is Dina’s understanding of Sydney’s developing sexuality.

Even as I Am Not Okay With This unfolds a narrative filled with bullies, pranks, and telekinesis, it does so with far more empathy than any version of Carrie. I won’t spoil here why Sydney wears a bloody party dress, but I can tell you this: it has nothing to do with a hateful mother or even the rejection of her peers. I Am Not Okay With This doesn’t deny the fact that we all feel different, nor the fact that people can be mean and behave horribly. It also refuses to believe that anyone is “normal,” insisting instead that there can be a community with other people okay with not being okay.

Joe George‘s writing has appeared at Think Christian, FilmInquiry, and is collected at joewriteswords.com. He hosts the web series Renewed Mind Movie Talk and tweets nonsense from @jageorgeii.