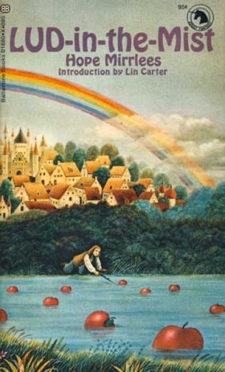

Lud-in-the-Mist is an unusual fantasy first published in 1926, before The Hobbit and considerably before the existence of fantasy as a marketing genre. It would be recognised as one of the founding works of the genre except for the way it has rarely been noticed and seldom reprinted. It’s a book that is itself in the tradition of Rossetti’s Goblin Market (1862) and Dunsany’s The King of Elfland’s Daughter (1924). It’s very clearly an influence on Susannah Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, and Neil Gaiman’s Stardust and the work of Greer Gilman, so perhaps it has contributed to a particular strand of fantasy, a particular way of approaching the numinous.

Lud-in-the-Mist is a sleepy comfortable settled town in Dorimare, a country that borders on Faery but which has turned its back on Faery and all the possibilities of Faery. The book is poised on that edge in which the uncanny spills into the mundane. It’s also beautifully written and a joy to read aloud. The theme, and the shape of the story, is pretty much that of The Bacchae, which isn’t unknown as a modern plot (Joanne Harris’s Chocolat) but is an unusual one to borrow, especially in this kind of setting. The story is shot through with folklore and country superstitions and the looming presence of the faery folk under the edges of the everyday.

We’re told in the first paragraph that Dorimare bordered on Fairyland, and then, immediately that “There had, of course, been no intercourse between the two countries for many centuries.” The mayor of Lud, Nathaniel Chanticleer, heard a note plucked from an old instrument, and the note was magical and changed the tone of his life.

It had generated in him what one can only call a wistful yearning after the prosaic things he already possessed. It was as if he thought he had already lost what he was holding in his hands. From this there sprang an ever present sense of insecurity, along with a distrust of the homely things he cherished…. Hence at times he would gaze on the present with the agonising tenderness with which one gazes at the past.

He suffers this strange affliction, and then his son eats fairy fruit. Fairy fruit is treated here like drug addiction, but also it’s very analogous to the way homosexuality was treated at the time Mirrlees was writing—something that feels good to the practitioner but something strongly disapproved of by society, something to grow out of, be cured of, and above all not to be mentioned in polite company. The people of Lud are so worried about fairy fruit that all mention of it has become completely taboo, and the laws banning it treat it as a kind of woven silk. I think it’s interesting to consider fairy fruit here as in Goblin Market as an analogy for “the love that dare not speak its name,” but it’s a subtext, not a laboured allegory. Whether or not Mirrlees intended this comparison, it’s reasonable to say that fairy fruit here takes the place of wine in The Bacchae and chocolate in Chocolat as the little madness that can spare you the greater madness, the little madness that gives flex to life.

The other very unusual thing about Lud-in-the-Mist as a novel is the way it’s set among the bourgeoisie. Nathaniel Chanticleer is a mayor, the town has thrived on trade, the masters of the town are merchants. The old aristocracy, Duke Aubrey and his court, have gone into Fairyland. Most fairy tales deal either with kings and princesses or with peasants—miller’s sons, girls who live in cottages and spin. Fantasy mostly goes with this. Lots of fantasy has kings coming back—here we have senators and masters and a trading republic, and that really is unusual. It’s without precedent and hasn’t been much copied either.

Lud-in-the-Mist is beautifully written, charming, funny, and always just a little creepy. It’s this combination that keeps bringing me back to it.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.