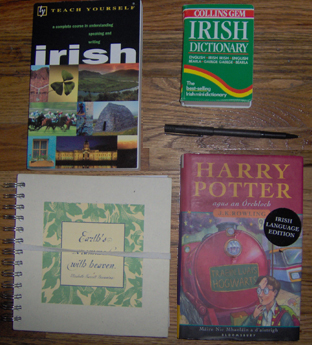

I’ve started a reading project that requires me to cart around all the stuff in the picture on the right: blank notebook, pen, Irish1 dictionary, Teach Yourself Irish, and the main feature, a copy of the first Harry Potter book in Irish. It’s called Harry Potter agus an Órchloch, or Harry Potter and the Golden Stone, and I’m only on page three after about nine hours with the book. Maybe half an hour was spent actually wading through new material, and the rest of the time went to looking up words in the dictionary, noting them with context in the notebook and paging through Teach Yourself Irish as a grammatical reference.

For example, you can’t just look up “órchloch” in the dictionary. You can try, but all you’ll get is “ór,” adjective, “golden.” There’s no entry for “chloch,” so it’s off to Teach Yourself Irish to look up adjectives and compound words; it turns out that most adjectives come after the word they describe, except for a few monosyllables like “ór.” When the adjective does come before the word, it causes an initial mutation known as séimhiú,2 a type of lenition where an “h” gets inserted after the first letter of the word. This turns the word “cloch,” with a hard “c” and throaty “ch,” into “chloch,” which is the sound I made when I first tried Jameson’s. It means “stone,” which makes sense, and when I apply my meager vocabulary and powers of deduction to the middle two words, we get Harry Potter and the Golden Stone.

I’m not quite crazy enough to tackle a totally unfamiliar language with a book and a dictionary, but like any graduate of an introductory course, my conversation is restricted to topics that Jane Austen would consider polite: the weather, the health of my family and what I did the other weekend. Reading Harry Potter would go faster if all they did was complain about the rain, announce the time, describe their clothing and go drinking a lot, but I’ll have to wait for the Irish Gossip Girl for that. A few times, as I sat with my materials arrayed around me on the living room floor or piled in my lap on the bus to Boston, I wondered exactly why I was doing this to myself. I haven’t taken three hours to read a single page since well, ever. And it’s not like I don’t know what happens.

Despite having nearly as much to lug around as Kate Nepveu and Leigh Butler for a re-read of relatively miniscule proportions, I’m having fun, and my geeky joys in the project are twofold: one is that I know I’m (very) slowly improving my Irish, and I hope that by the time I finish Chapter 1 that it’ll only take me an hour a page. There are faster ways to learn a language, but few of them include the phrase “SCÓR AG GRYFFINDOR!” I like singing songs in Irish and I’d love to read poetry in Irish; once I master the modern dialect (read: once conjugating verbs in the past tense stops making me break out in a cold sweat), then Old Irish can’t be that hard, right? Then I could read the Ulster Cycle in the original. In short, I’m a Hibernophile all over.

The other thing that’s fun is just that I have to pick my way through the book so slowly, sentence by word by consonant mutation. The last book I read in another language was Alanna La Guerrera, a Spanish translation of Tamora Pierce’s Alanna: The First Adventure. I read more slowly in Spanish, so it made me linger over moments and images that I might have rushed past in English, but it’s still a book I’ve read umpteen times in English in a language I studied for fourteen years. I’ve stopped laboring over the fine points of Spanish grammar, but every little thing in Irish throws me off my game. I have to think constantly about whether “a” means “his,” “hers,” or “theirs” at any given moment, whether that prepositional phrase means “to have” or “to know,” and how on earth “bhfaca” and “chonaic” can both be forms of the verb “féic.”3 It’s not the same as my Irish-specific geeky joy; puzzling out sentences feels more like doing math or playing a video game, but even better because I’m still tinkering with language. As I said, I know what happens in the book, so reading a sentence two, three, or ten times until I have it all figured out doesn’t frustrate me; quite the opposite, in fact.

Does anyone else read in a language you’re not fluent in? Why? How does it affect your reading? What do you read? I can’t be the only nutter with a dictionary in Tor.com-land.

1 “Irish you mean, like, Gaelic?” Say this to the wrong Irishman and you will get punched. The way my first Irish teacher explained it to me was that, sure, the Irish word for the Irish language is “Gaeilge,” which sounds a lot like “Gaelic,” but “Gaelic” could just as well apply to any of the Goidelic languages (Irish, Scottish and Manx). Calling it “Irish” connects it to Ireland and the Irish people; there was also something about the English being the ones to coin “Gaelic.” I mostly know that my friends in Cork who were into Irish were picky about it, so in an effort not to get called an amadán,4 I picked up the habit.

2 Pronounced “SHAVE-you.” Means the funny grammar thing.

3 Pronounced “fake.” Means “see.”

4 Pronounced “AM-a-don.” Means idiot.5

5 Pronounced “EE-jit.”