The goal of building a fictional world isn’t to build a world. It’s to build a metaphor. And the success of the world you build isn’t measured by how complete or coherent or well-mapped the world is. It’s measured by whether the world and the meaning map onto each other.

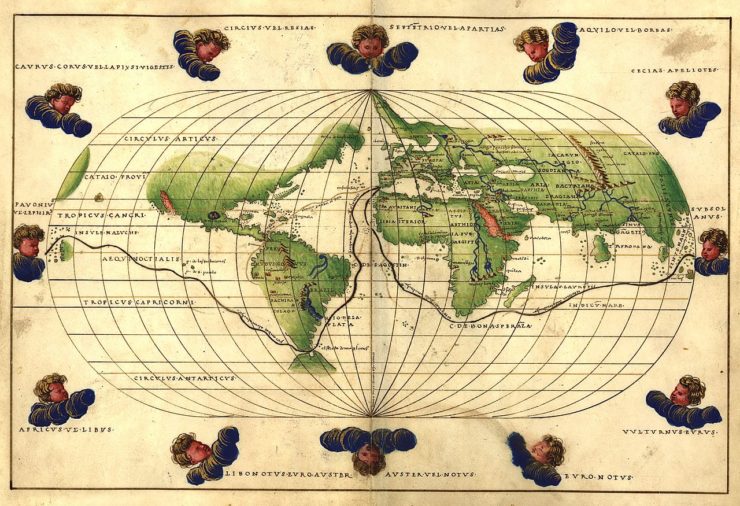

Arguments about worldbuilding in SFF don’t generally focus on metaphors. Instead they often focus, somewhat paradoxically, on realism. How can you best make a world that feels as detailed and rich and coherent as the world you’re living in now, complete with impeachment trials, global warming, pandemics, pit bulls, and K-pop? Should you, in the manner of Tolkien, systematically construct every detail of your fantasy realm, with maps and histories and even complete languages? Or should you leave spaces to suggest vast uncharted bits? Maybe sometimes it’s more evocative not to tell your readers what lives on every part of the map, or what the Elvish means. As China Mieville says, “A world is going to be compelling at least as much by what it doesn’t say as what it does. Nothing is more drably undermining of the awe at hugeness that living in a world should provoke than the dutiful ticking off of features on a map.”

But sometimes left out of these discussions is the idea that authors aren’t always trying to create worlds that feel real, or complete, or even particularly huge. To map or not to map isn’t just a question of finding the best cartographic technique to arrive at the same mound of Mordor. The discussion of which way to get where can leave out the many possible Wheres in fiction—and that the journey and the destination are often tied together like the braided colons of the purple space critters of Br’leyeh. Which is very tied together indeed.

Again—and unlike the whimsical purple colons of Br’layah—Tolkien’s Middle-earth is famous for its careful construction. That’s part of the fun of the book. The sense of the combined weight of mystery and history and language all carefully and lovingly delineated isn’t there because Tolkien abstractly believed that all fantasy worlds should start with linguistics. Rather, Tolkien creates a complete world because he is writing about the threat of civilizational collapse. He builds his world up because he wants his readers to be invested in the detail and the craft, so that they feel a sense of loss and fear when all that detail and craft is threatened. Faced with two world wars and an existential threat to the rich history he loved, Tolkien poured his love of a passing era into the creation of his own rich history. Middle-earth holds together so well precisely because it is a reaction, and a response, to a real world which seemed to be coming apart.

Buy the Book

The Witness for the Dead

Tolkien’s worldbuilding is essentially inspired by nostalgia. It’s fitting that he’s had so many imitators, who draw new maps to return to versions of Middle-earth, just as Tolkien drew his maps of Middle-earth as a way of returning to an England that seemed to be slipping away.

Still, there are plenty of interesting epic fantasy variations and explorations that aren’t bent on re-memorializing the Shire. Jacqueline Carey’s Kushiel’s Dart (2001), for example, is an intricately detailed alternate Europe in which Christianity never gained a foothold as a cultural force. Free of repressive attitudes and doctrines surrounding sex, Carey’s world is one of sensual pleasure and sophistication, though increasingly threatened by callous northern barbarians. Like Tolkien’s world, hers is a monument of completeness. But she switches Tolkien’s terms, so that readers end up fearing the loss of an urbane sophisticated cosmopolis, rather than a sturdy rural England. It’s epic fantasy for Remainers.

Carey and Tolkien show that sweepingly meticulous worldbuilding can sustain different metaphors and meanings in its towers and boudoirs. But sometimes what an author has to say isn’t meticulous, but vague or confusing. Philip K. Dick, for one, is an author who famously wrote about how reality didn’t make any sense by creating worlds that didn’t fit together. His novels and stories are often train wrecks of worldbuilding (or even world wrecks of train building).

In Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (1968), for example, Dick imagines a future world in which human-like androids have been developed to do menial tasks. The hero, Deckard, is a bounty hunter employed to retire (i.e., kill) androids when they go rogue. Deckard works closely with the police. But at one point in the book, he is captured by a policeman he doesn’t know, and taken to a completely different fully staffed police station. Deckard lays out the illogic himself:

It makes no sense…. Who are these people? If this place has always existed, why didn’t we know about it? And why don’t they know about us? Two parallel police agencies, he said to himself; ours and this one. But never coming in contact—as far as I know—until now. Or maybe they have, he thought. Maybe this isn’t the first time. Hard to believe, he thought, that this wouldn’t have happened long ago. If this really is a police apparatus here; if it’s what it asserts itself to be.

The book suggests that either all the police are fake androids, or that Deckard himself is an android—explanations which don’t really answer any of the questions Deckard lays out above.

Thematically, though, the fake police station makes perfect (non)sense. Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? is a novel about how the boundaries of who is and isn’t considered human, or part of the community, are essentially arbitrary. It questions the policing of deviance. And how better to do that than to create a world in which the police themselves are an ersatz anomaly? We never learn really what the police station is or why it’s there any more than we ever learn why Gregor Samsa wakes up as a giant insect. The worldbuilding is off, broken, and incomprehensible because the world itself is off, broken, and incomprehensible.

Colson Whitehead’s 2016 novel Underground Railroad is even more explicit in its refusal to cohere. Initially, the novel seems to be in the tradition of antebellum slave narratives. That’s a genre that was devoted to realism, or to what might be called the worldbuilding of verisimilitude. Slave narratives were political documents, intended to convince the public of the truth of the suffering of enslaved people and to inspire them to action for change. Solomon Northup’s memoir Twelve Years a Slave (1853), to cite one example, includes lengthy discussions about the details of cotton farming. To readers now, these details may seem tedious and unnecessary. But at the time they no doubt were meant to demonstrate that Northup really had been held in bondage on a plantation, and that his account was true.

Contemporary depictions of slavery, like the movie 12 Years a Slave, often adopt a similar realist approach. Whitehead, though, does something different. Underground Railroad opens with the protagonist Cora in bondage in Georgia before the Civil War. But when she escapes, the world starts to fracture. She travels to South Carolina, where there is no slavery. Instead, whites sterilize Blacks and spout eugenic ideology that didn’t become popular until the late 19th and early 20th century. In Indiana, whites launch violent attacks on Black communities, as they did in the post-Reconstruction era. Whitehead’s North Carolina has instituted a regime of extermination similar to the Nazis; Cora has to hide out like Anne Frank and other Jewish people hidden by non-Jewish resistors. The spatial map of the United States is turned into a temporal map of injustice. All of history is compressed into a nightmare landscape that is as nonsensical and inescapable as American racism itself.

The point again isn’t that coherent worldbuilding is right or wrong. The point is that the coherence of fiction is part of what that fiction says to the reader. Walter Tevis’ The Hustler (1959) puts you in pool halls grimy and solid enough that you can feel the cue chalk under your fingernail because it’s a story about a guy facing the ugly truths of existence. Joanna Russ’ The Female Man (1975) creates several only partially realized alternate worlds as a way of suggesting the tentative, contingent nature of opposition to patriarchy—and the tentative, contingent nature of patriarchy itself. Terry Pratchett’s Discworld is a flat disc carried on the back of a bunch of turtles, and if you have ever read Terry Pratchett you know why those turtles are at home in his prose.

Some writers imagine carefully crafted realms. Some imagine realms with holes in them, realms that defy logic or seem impossible. But whatever universe you have in your head, there is no place divorced from the meaning of that place. What we say about the world can’t be teased apart from what the world is—we can’t imagine a world without meaning. We live in a land called metaphor. Even its cartography is a symbol.

Thanks to Jeannette Ng, who helped me think through some of these ideas on Twitter.

Noah Berlatsky is the author of Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics (Rutgers University Press).

Personally I world build for fun. Tolkien’s thing was language mine is anthropology. And like Mr. Bilbo Baggins I dearly love a map!

Discworld is carried on the back of only one turtle, Great A’Tuin.

I know this is a subjective topic, but I will say that Kushiel’s Dart did not impress me in the world-building department. “Europe with a coat of fantasy paint” is not exactly unique, even if it is special sexy fantasy paint.

@1 – I don’t recall but are you a fan of CJ Cherryh? She is an anthropologist by training and most of her novels are incredible cultural deep dives – especially the Foreigner series.

Thank you!

This is a point I’ve been trying (only less coherently) to make for ages. The point of world-building isn’t to put a map in and check travel distances and whether it’s believably medieval. The historicity flew out when the dragons flew in.

It’s nice not to have something throw you out by having a steampunk or modern element in an otherwise medieval background, and wonder where they got the Bessemer Process early, for example, but it’s most important that a fantasy is coherent by its own internal rules rather than by the external consistency of the real world.

One of my favourite fantasy series is Sheri Tepper’s Marianne trilogy, and it’s nowhere weakened by the use of strongly realised dreamscapes where the character, say, is trapped working in a library where she cannot escape.

Incidentally, I think you should have added Seanan McGuire’s Wayward Children: the entire set of world-building is about portals to different worlds that work on different rules (including Sense/Nonsense instead of Good/Evil).

Portal fantasies are good that way. Narnia is another one which doesn’t really work as an independent whole because the society is romanticised-medieval with parts that suit it as ill as Father Christmas and anthropomorphised animals and classical gods and spirits. But it works because Lewis put his heart and soul into it, a childlike creation with dreamlike elements rather than something that holds together for grown-up people or grown-up reasons.

Hear, here! Perhaps the moderators can start dropping a link to this essay when discussions get too heated regarding arcane elements of fictional worlds. ;-)

Yet the last two paragraphs seem to muddy an important point that I think can be expressed more succinctly: worldbuilding is just one tool at a storyteller’s disposal, no more or less important, in the abstract, than characterization, plot development, theme/symbolism, or any other literary element. Worldbuilding should be judged by the way it works in conjunction with those other elements to create a story that has impact on its audience.

A reminder to keep the tone of the comments civil and constructive–don’t be rude or dismissive if you want to take part in the discussion. The full commenting guidelines can be found here.

I love a good map! I will go back and forth between a story and a map to track the progress of the heros, and revel in the dorky geekiness!

When I am reading a work of fiction set in a “created” world and I find myself wondering about its inconsistencies or implausibilities, that usually means that I am not finding the characters or story compelling enough, and that is the real “problem” with that work of fiction. Sure, sometimes after I’ve read it I’ll think back about some aspect of the world that didn’t add up, but at the time I was reading it, if that was not an issue for me, I still think the world of the book is successful.

@10,

I agree: noticing inconsistencies in world-building indicates, to me at least, that the story-building isn’t strong enough.

The world of the story, from something as close to real as the Boston of Robert Parker’s Spenser to something as far away as Yoon Ha Lee’s Hexarchate has to be good enough, but inconsistencies are to be expected. They show up in many places: The Hobbit, in what appears to be pre-1492 Europe, with potatoes and tobacco, didn’t kick me out, but many fantasies (I’m looking at you, GoT on HBO) where pre-motor vehicle travel takes hours instead of weeks, or where wounds, especially head injuries, heal in a few hours or even minutes.

I’m not particularly picky in this regard, that is I don’t read fiction with a highlighter, notepad, and sticky notes, but I’ve a good memory, so I may notice that the hero’s horse’s name changed from Benny to Bonny, but I have a threshold.

@11. swampyyankee: In all honesty it’s a lot more fun to look for these little inconsistencies with a view to using them to build on our understanding of the setting – regarding them as Untold Tales, rather than a mortal insult to the discerning client (for example: the horse might have switched from ‘Benny’ to ‘Bonny’ because somebody thought they had a gelding when they were actually riding a mare … and are doing their best to avoid bringing this up, because the horse was acquired ‘on the fly’).

I love it when an author lets the world build around the story, but then is also meticulous about consistency. STP’s Discworld is probably my favorite example of this, where even throwaway lines from the first 2-3 books where a life-spanning saga wasn’t expected are – by and large – maintained and treated as canon by the rest of the series. Is it perfect? No, but its remarkable, and explaining and jumping into maintaining that consistency with eyes wide open instead of hand-waving it away actually produces some remarkable opportunities for fiction.

@@.-@ I adore her Chanur saga as well for the same reason; building even a fairly sparse alien world sufficiently well that humans behaving stereotypically become strange – and more remarkably, feel natural as the strangers.

It doesn’t have to be meticulous, but I do appreciate consistency. I’m a fan of alternate histories and few things will jar me from a book than reading about how some major event changed everything two thousand years ago… and we hear about it as two characters walk through Washington DC. Or that dinosaurs never died out, which was something that had to be considered when they ratified the Constitution in 1787.

In general, I want enough detail that I can believe the whole but not so much detail that things fall apart at first consideration. Like the Star Wars films. The original trilogy is pretty spare in its world building. You an Empire and the Rebellion that have existed for… an extended yet indeterminate period of time. Done. The sequel has the New Republic and the First Order (which came from…?) and a Resistance? All in twenty years? Oh and let’s not forget the fuel. And the weapon dealers. It’s detailed, but clashes with what’s come before.

Tell me enough that I can believe in it and stay on the fun train.

I agree with @15, which is why alternate versions of our world are a hard sell for me sometimes. They’re not different enough. It’s like the set is only finished where the camera is pointing, and if you went round the back it would all be wood and canvas and paint. Like Temeraire, where implausibly large dragons that can be ridden by multiple humans somehow can both fly and also don’t create impossible supply problems, plus they’ve existed for centuries but we still have Napoleon and the Napoleonic Wars. Though at least the history of some other parts of the world, like South America, was different.

(I especially have a problem with travel to alternate worlds where major things, sometimes up to and including evolutionary biology, are different, but somehow versions of the characters still exist, and may even live in the same house which opens with the same key. But that’s another issue.)

I could see how you may think that’s the metaphor of Jacqueline Carey’s world, if you’ve only read the first book.

I’ve found the overarching message in her books is more about cultural differences and misunderstandings, the general goodness of common people, that all world religions and philosophical paths are just divergent routes to the same destination, how people after power will twist and corrupt sacred ideas towards their own end, and how good people, through brave deeds, can rectify what has been done by evil or selfish ones.

And, of course, Love as thou wilt.

P.S. It’s not only that Christianity never took hold, it’s more that when Yeshua (Jesus) was killed, a new God/Angel (Elua) was born from the admixture of the Yesuite (Jewish) God’s blood and the Magdalene’s tears, and nurtured by Gaia. He is persecuted as a false child of God, and eight of God’s angels revolt from heaven in order to come to Earth and save him. They comingle with mortals, their descendants creating the nation of Terre d’Ange.

Besides this, the other key difference is that most major civilizations from history are coexisting in some form or another (Carthage, Rome, Greece, Egypt, Meso- America, China, India, Babylon, Mongolia, Scandinavian, Jewish, Celts, Gauls, and Persian, just off the top of my head.)

A bunch of turtles? A bunch of turtles?! Do you refer to Great A’Tuin?!