I was lucky enough to grow up in an age when people weren’t as worried about safety. Especially transportation safety. That’s why:

- I remember the brief glorious moment of flight when jumping an old beater car over a railway crossing, followed by the thud when the engine falls out on touchdown;

- I know the exact sound of a windscreen and face collision after an abrupt stop;

- I know how fast a VW Beetle has to take a corner before the kid riding the running board flies off;

- I can boast of walking four miles through a blizzard after breaking four ribs in a mid-winter car wreck.

It was a glorious time to be alive.

Science fiction offers even more exotic transportation choices—choices that even I would avoid. Here are six of them.

The Orion Drive

Poul Anderson’s Orion Shall Rise (1983) is a tale of conflict between technological exuberance (on the part of the Northwest Union) and technological prudence (on the part of the conservationist Maurai). The Northwest Union is planning to use what advocates might call “externally pulsed plasma propulsion” and skeptics might call “riding a series of small nuclear explosions from which your pusher plate may or may not protect you.” The Orion drive was an actual proposal, the brainchild of Ted Taylor and Freeman Dyson. It offered a rare combination of high Delta-v and high acceleration at the cost of, well, pretty much everything implied by “a series of small nuclear explosions.”

Advocates of Project Orion were sure that the engineering challenges were surmountable, but since the Partial Test Ban in 1963 effectively doomed efforts to build one, we will never know. We can only guess. All I know is that I wouldn’t ride a spaceship where the barrier between me and a nuclear detonation, even a very small one, was an ablative plate assembled by the lowest bidder1.

Matter-to-Energy Conversion

Steve Gallacci’s Albedo: Birthright (1985) is a sequel to his mil-SF comic, Albedo: Erma Felda: EDF. It is set in a time when civilization was recovering from an interstellar dark age. Its characters sometimes gain possession of imperfectly understood ancient technology. Ancient starships seem to offer renewed access to the stars but…there is a catch. The ships are powered by total conversion of matter to energy. Failure modes include turning all matter in contact with the power plant into energy. This is bad enough if the starship is still in deep space; it’s worse if it’s on a planet at the time2.

Hyperspace

John E. Stith’s Redshift Rendezvous (1990) features journeys through a hyperspace where the speed of light is only ten meters a second. While this does allow space travel (as well as Mr Tomkins-style physics lectures), I don’t think it would be a good idea. At least not for meatsack me—my biochemistry has been honed by billions of years of evolution in an environment in which the speed of light is about 300,000 kilometers per second. I am not at all convinced that said biochemistry would keep functioning if you changed a fundamental physical constant.

Subatomic Particle Energy

Bob Shaw’s A Wreath of Stars (1976) and Gregory Benford’s The Stars in Shroud (1978) use similar conceits, if for rather different purposes. In Wreath, conversion from regular matter to anti-neutrinos3 affords its protagonist escape from an irate dictator. He finds himself in an intangible world (which is doomed, so it wasn’t much of an escape). In the Benford novel, conversion to tachyons allows faster than light travel. In addition to issues I will discuss in a later essay, both of these technologies have the same apparent drawback, namely: unless the process is absolutely instant (I don’t see how it could be) this would probably shear all the complex molecules and chemical structures in one’s meatsack body, as different bits are converted at slightly different times. Do not want to be converted to mush, fog, or plasma. No thanks.

One-Way Teleporters

Lloyd Biggle, Jr.’s All The Colors of Darkness (1963) and Harry Harrison’s One Step From Earth (1970) both use teleportation devices whose portals are one-way only. When I was young, I worried about what might happen to molecular bonds as one passed through a one-way barrier that was impervious to forces in the other direction. Later in life I decided that these were event horizons and might permit safe transit. What kills you in a black hole isn’t the event horizon but the tides and the singularity. BUT…what happens to someone halfway through one of these if the person behind them becomes impatient, grabs the traveller by their backpack, and yanks them backwards? What happens if you trip while partway through? (Nothing good, is my guess.)

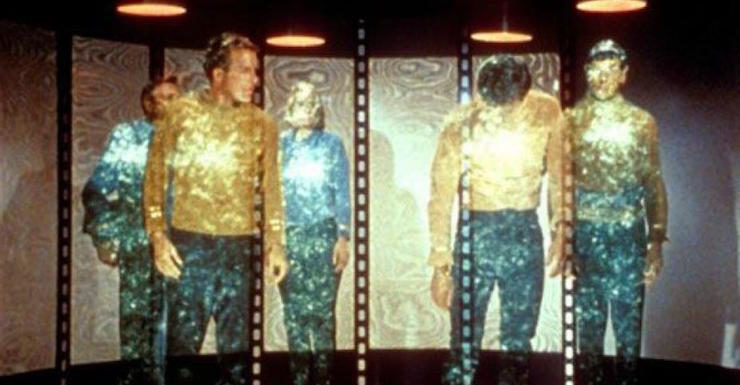

Transporters

Finally, I am leery of any teleportation system that depends on destructive scanning and distant replication; examples range from Anderson’s The Enemy Stars (1958) to some versions of Star Trek. Very small errors could result in unpleasant consequences, as demonstrated in that unimpeachable historical document, Galaxy Quest:

There are other problems with this mode of transport. Consult your friendly internet for a whole lot of angry argument re: this matter.

This segues into a worry I had as a six-year-old: does identity survive when every atom of one’s body is replaced? This occupied my thoughts quite a lot in 1967 and 1968, as my seventh birthday was approaching. My parents had once mentioned that all the atoms in one’s body were replaced every seven years. They neglected to add that this was a continual, gradual process4. I was under the impression that it would happen all at once on my seventh birthday. I wasn’t at all sure I’d still be me afterward. Although I could see why the duplicate might think it was.

Now, I think continuity of identity over the years is merely comforting illusion—still, I am not stepping into a zap-and-duplicate teleporter. But don’t let me stop you.

Buy the Book

Worlds Seen in Passing: Ten Years of Tor.com Short Fiction

1: Merely declining to use the device wouldn’t necessarily protect you from it. Externalities of the Orion Drive included non-zero death rates from fallout and the chance that one could fry satellites in orbit. But of course in those days, there was no globe-spanning satellite network. Most of the radioactive debris from higher altitude detonations would end up in Canada and other polar latitudes, where nobody associated with the project lived. An acceptable cost.

2: Murray Leinster’s much earlier Proxima had a very similar arrangement and an actual, on-stage, demonstration of the failure mode.

3: Bob Shaw was not a hard-SF author.

4: Similar confusion reigned when my parents relayed to me the sad news the family cat had been run over by teenagers. I am very, very literal-minded. I was not told that the teenagers were riding in a car at the time.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.

Do you technically die when using a transporter? Let’s say the soul is real and there’s an afterlife. If you use a transporter, do you die and your soul moves on to the afterlife? Does your replacement at the destination have it’s own soul? Was it instantly created?

Like a human fax machine?

Not really? Would you like to see my human fax machine?

Not really?

Couldn’t resist.

Oh, here we go. Cue the the edgy “transporters are murder machines” crowd. No, just no.

Hill hopping. In a 73 Pontiac Grand Am with a 400 cubic inch V-8. And somewhat questionable brakes. While not realizing there was a car stopped on the other side of the hill. Fortunately the brakes worked that time. Later, for some reason, a head gasket blew. Most of the local hills that could be hopped have been somewhat tamed by the highway department.

“Footfall” by Niven and Pournelle has an Orion powered spaceship launching from Puget Sound.

” the family cat had been run over by teenagers.”

Rather the opposite happened to me this summer. I was home in Canada, my dog was still in the UK. My dog sitter texted me and said “some guy” had run over my dog in the park. Then talked as if nothing significant had happened. I had to guess that he didn’t really mean run over by a car, as they shouldn’t be in the park. So, I waited until morning before asking “WTF? Run over…how?”

And no, she wasn’t hurt.

The fine structure constant is proportional to e^2/c (where e is the fundamental electric charge). If you are depressing only c, electromagnetism gets stronger with unknown but presumably large effects on chemistry as a whole as electrons now pull at each other much harder.

(And what about the protons in the nucleus? Did you just make electomagnetic repulsion between them stronger than the strong force holding the whole thing together?)

3: I think one can argue either side of the transporters = murder machines perfectly validly. What counts as sufficient continuity varies from person to person.

See also Wil McCarthy’s Fax machines, which also allow editing on the fly. Which I guess is one way to avoid qualms about whether or not the version at the far end is the same as the one who went in: just edit those out.

I _think_ Linda Nagata’s Vast had a side plot about someone who edited certain qualms out of their copies without informing them they’d been edited. The original died, leaving no hint the duplicates were … not quite faithful to the original.

“Think Like A Dinosaur” transporters. If anything goes wrong …

And isn’t it about time someone wrote a novel or story called “A Nicoll Event”?

duplicate comment/throw out airlock

@9

Sure it wasn’t a a transporter reflection in an ion storm?