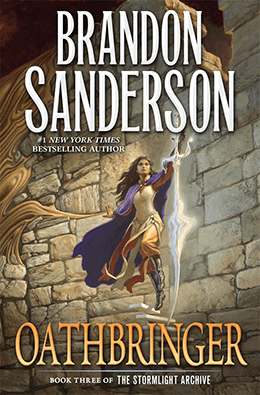

Start reading Oathbringer, the new volume of Brandon Sanderson’s Stormlight Archive epic, right now. For free!

Tor.com is serializing the much-awaited third volume in the Stormlight Archive series every Tuesday until the novel’s November 14, 2017 release date.

Every installment is collected here in the Oathbringer index.

Need a refresher on the Stormlight Archive before beginning Oathbringer? Here’s a summary of what happened in Book 1: The Way of Kings and Book 2: Words of Radiance.

Spoiler warning: Comments will contain spoilers for previous Stormlight books, other works that take place in Sanderson’s cosmere (Elantris, Mistborn, Warbreaker, etc.), and the available chapters of Oathbringer, along with speculation regarding the chapters yet to come.

Chapter 4

Oaths

I know that many women who read this will see it only as further proof that I am the godless heretic everyone claims.

—From Oathbringer, preface

Two days after Sadeas was found dead, the Everstorm came again.

Dalinar walked through his chambers in Urithiru, pulled by the unnatural storm. Bare feet on cold rock. He passed Navani—who sat at the writing desk working on her memoirs again—and stepped onto his balcony, which hung straight out over the cliffs beneath Urithiru.

He could feel something, his ears popping, cold—even more cold than usual—blowing in from the west. And something else. An inner chill.

“Is that you, Stormfather?” Dalinar whispered. “This feeling of dread?”

This thing is not natural, the Stormfather said. It is unknown.

“It didn’t come before, during the earlier Desolations?”

No. It is new.

As always, the Stormfather’s voice was far off, like very distant thunder. The Stormfather didn’t always reply to Dalinar, and didn’t remain near him. That was to be expected; he was the soul of the storm. He could not—should not—be contained.

And yet, there was an almost childish petulance to the way he sometimes ignored Dalinar’s questions. It seemed that sometimes he did so merely because he didn’t want Dalinar to think that he would come whenever called.

The Everstorm appeared in the distance, its black clouds lit from within by crackling red lightning. It was low enough in the sky that—fortunately—its top wouldn’t reach Urithiru. It surged like a cavalry, trampling the calm, ordinary clouds below.

Dalinar forced himself to watch that wave of darkness flow around Urithiru’s plateau. Soon it seemed as if their lonely tower were a lighthouse looking over a dark, deadly sea.

It was hauntingly silent. Those red lightning bolts didn’t rumble with thunder in the proper way. He heard the occasional crack, stark and shocking, like a hundred branches snapping at once. But the sounds didn’t seem to match the flashes of red light that rose from deep within.

The storm was so quiet, in fact, that he was able to hear the telltale rustle of cloth as Navani slipped up behind him. She wrapped her arms around him, pressing against his back, resting her head against his shoulder. His eyes flickered down, and he noticed that she’d removed the glove from her safehand. It was barely visible in the dark: slender, gorgeous fingers—delicate, with the nails painted a blushing red. He saw it by the light of the first moon above, and by the intermittent flashes of the storm beneath.

“Any further word from the west?” Dalinar whispered. The Everstorm was slower than a highstorm, and had hit Shinovar many hours before. It did not recharge spheres, even if you left them out during the entire Everstorm.

“The spanreeds are abuzz. The monarchs are delaying a response, but I suspect that soon they’ll realize they have to listen to us.”

“I think you underestimate the stubbornness a crown can press into a man or woman’s mind, Navani.”

Dalinar had been out during his share of highstorms, particularly in his youth. He’d watched the chaos of the stormwall pushing rocks and refuse before it, the sky-splitting lightning, the claps of thunder. Highstorms were the ultimate expression of nature’s power: wild, untamed, sent to remind man of his insignificance.

However, highstorms never seemed hateful. This storm was different. It felt vengeful.

Staring into that blackness below, Dalinar thought he could see what it had done. A series of impressions, thrown at him in anger. The storm’s experiences as it had slowly crossed Roshar.

Houses ripped apart, screams of the occupants lost to the tempest.

People caught in their fields, running in a panic before the unpredicted storm.

Cities blasted with lightning. Towns cast into shadow. Fields swept barren.

And vast seas of glowing red eyes, coming awake like spheres suddenly renewed with Stormlight.

Dalinar hissed out a long, slow breath, the impressions fading. “Was that real?” he whispered.

Yes, the Stormfather said. The enemy rides this storm. He’s aware of you, Dalinar.

Not a vision of the past. Not some possibility of the future. His kingdom, his people, his entire world was being attacked. He drew a deep breath. At the very least, this wasn’t the singular tempest that they’d experienced when the Everstorm had clashed with the highstorm for the first time. This seemed less powerful. It wouldn’t tear down cities, but it did rain destruction upon them—and the winds would attack in bursts, hostile, even deliberate.

The enemy seemed more interested in preying upon the small towns. The fields. The people caught unaware.

Though it was not as destructive as he’d feared, it would still leave thousands dead. It would leave cities broken, particularly those without shelter to the west. More importantly, it would steal the parshmen laborers and turn them into Voidbringers, loosed on the public.

All in all, this storm would exact a price in blood from Roshar that hadn’t been seen since… well, since the Desolations.

He lifted his hand to grasp Navani’s, as she in turn held to him. “You did what you could, Dalinar,” she whispered after a time watching. “Don’t insist on carrying this failure as a burden.”

“I won’t.”

She released him and turned him around, away from the sight of the storm. She wore a dressing gown, not fit to go about in public, but also not precisely immodest.

Save for that hand, with which she caressed his chin. “I,” she whispered, “don’t believe you, Dalinar Kholin. I can read the truth in the tightness of your muscles, the set of your jaw. I know that you, while being crushed beneath a boulder, would insist that you’ve got it under control and ask to see field reports from your men.”

The scent of her was intoxicating. And those entrancing, brilliant violet eyes.

“You need to relax, Dalinar,” she said.

“Navani…” he said.

She looked at him, questioning, so beautiful. Far more gorgeous than when they’d been young. He’d swear it. For how could anyone be as beautiful as she was now?

He seized her by the back of the head and pulled her mouth to his own. Passion woke within him. She pressed her body to his, breasts pushing against him through the thin gown. He drank of her lips, her mouth, her scent. Passionspren fluttered around them like crystal flakes of snow.

Dalinar stopped himself and stepped back.

“Dalinar,” she said as he pulled away. “Your stubborn refusal to get seduced is making me question my feminine wiles.”

“Control is important to me, Navani,” he said, his voice hoarse. He gripped the stone balcony wall, white knuckled. “You know how I was, what I became, when I was a man with no control. I will not surrender now.”

She sighed and sidled up to him, pulling his arm free of the stone, then slipping under it. “I won’t push you, but I need to know. Is this how it’s going to continue? Teasing, dancing on the edge?”

“No,” he said, staring out over the darkness of the storm. “That would be an exercise in futility. A general knows not to set himself up for battles he cannot win.”

“Then what?”

“I’ll find a way to do it right. With oaths.”

The oaths were vital. The promise, the act of being bound together.

“How?” she said, then poked him in the chest. “I’m as religious as the next woman—more than most, actually. But Kadash turned us down, as did Ladent, even Rushu. She squeaked when I mentioned it and literally ran away.”

“Chanada,” Dalinar said, speaking of the senior ardent of the warcamps. “She spoke to Kadash, and had him go to each of the ardents. She probably did it the moment she heard we were courting.”

“So no ardent will marry us,” Navani said. “They consider us siblings. You’re stretching to find an impossible accommodation; continue with this, and it’s going to leave a lady wondering if you actually care.”

“Have you ever thought that?” Dalinar said. “Sincerely.”

“Well… no.”

“You are the woman I love,” Dalinar said, pulling her tight. “A woman I have always loved.”

“Then who cares?” she said. “Let the ardents hie to Damnation, with ribbons around their ankles.”

“Blasphemous.”

“I’m not the one telling everyone that God is dead.”

“Not everyone,” Dalinar said. He sighed, letting go of her—with reluctance—and walked back into his rooms, where a brazier of coal radiated welcome warmth, as well as the room’s only light. They had recovered his fabrial heating device from the warcamps, but didn’t yet have the Stormlight to run it. The scholars had discovered long chains and cages, apparently used for lowering spheres down into the storms, so they’d be able to renew their spheres—if the highstorms ever returned. In other parts of the world, the Weeping had restarted, then fitfully stopped. It might start again. Or the proper storms might start up. Nobody knew, and the Stormfather refused to enlighten him.

Navani entered and pulled the thick drapings closed over the doorway, tying them tightly in place. This room was heaped with furniture, chairs lining the walls, rolled rugs stacked atop them. There was even a standing mirror. The images of twisting windspren along its sides bore the distinctly rounded look of something that had been carved first from weevilwax, then Soulcast into hardwood.

They had deposited all this here for him, as if worried about their highprince living in simple stone quarters. “Let’s have someone clear this out for me tomorrow,” Dalinar said. “There’s room enough for it in the chamber next door, which we can turn into a sitting room or a common room.”

Navani nodded as she settled onto one of the sofas—he saw her reflected in the mirror—her hand still casually uncovered, gown dropping to the side, exposing neck, collarbone, and some of what was beneath. She wasn’t trying to be seductive right now; she was merely comfortable around him. Intimately familiar, past the point where she felt embarrassed for him to see her uncovered.

It was good that one of them was willing to take the initiative in the relationship. For all his impatience to advance on the battlefield, this was one area in which he’d always needed encouragement. Same as it had been all those years ago…

“When I married last,” Dalinar said softly, “I did many things wrong.

I started wrong.”

“I wouldn’t say that. You married Shshshsh for her Shardplate, but many marriages are for political reasons. That doesn’t mean you were wrong. If you’ll recall, we all encouraged you to do it.”

As always, when he heard his dead wife’s name, the word was replaced to his hearing with a breezy sound of rushing air—the name couldn’t gain purchase in his mind, any more than a man could hold to a gust of wind.

“I’m not trying to replace her, Dalinar,” Navani said, suddenly sounding concerned. “I know you still have affection for Shshshsh. It’s all right. I can share you with her memory.”

Oh, how little they all understood. He turned toward Navani, set his jaw against the pain, and said it.

“I don’t remember her, Navani.”

She looked to him with a frown, as if she thought she hadn’t heard him correctly.

“I can’t remember my wife at all,” he said. “I don’t know her face. Portraits of her are a fuzzy smudge to my eyes. Her name is taken from me whenever spoken, like someone has plucked it away. I don’t remember what she and I said when we first met; I can’t even remember seeing her at the feast that night when she first arrived. It’s all a blur. I can remember some events surrounding my wife, but nothing of the actual details. It’s all just… gone.”

Navani raised her safehand fingers to her mouth, and from the way her brow knit with concern, he figured he must look like he was in agony.

He slumped down in a chair across from her. “The alcohol?” she asked softly.

“Something more.”

She breathed out. “The Old Magic. You said you knew both your boon and your curse.”

He nodded. “Oh, Dalinar.”

“People glance at me when her name comes up,” Dalinar continued, “and they give me these looks of pity. They see me keeping a stiff expression, and they assume I’m being stoic. They infer hidden pain, when really I’m just trying to keep up. It’s hard to follow a conversation where half of it keeps slipping away from your brain.

“Navani, maybe I did grow to love her. I can’t remember. Not one moment of intimacy, not one fight, not a single word she ever said to me. She’s gone, leaving debris that mars my memory. I can’t remember how she died. That one gets to me, because there are parts of that day I know I should remember. Something about a city in rebellion against my brother, and my wife being taken hostage?”

That… and a long march alone, accompanied only by hatred and the Thrill. He remembered those emotions vividly. He’d brought vengeance to those who had taken his wife from him.

Navani settled down on the seat beside Dalinar, resting her head on his shoulder. “Would that I could create a fabrial,” she whispered, “to take away this kind of pain.”

“I think… I think losing her must have hurt me terribly,” Dalinar whispered, “because of what it drove me to do. I am left with only the scars. Regardless, Navani, I want it to be right with us. No mistakes. Done properly, with oaths, spoken to you before someone.”

“Mere words.”

“Words are the most important things in my life right now.”

She parted her lips, thoughtful. “Elhokar?”

“I wouldn’t want to put him in that position.”

“A foreign priest? From the Azish, maybe? They’re almost Vorin.”

“That would be tantamount to declaring myself a heretic. It goes too far. I will not defy the Vorin church.” He paused. “I might be willing to side-step it though.…”

“What?” she asked.

He looked upward, toward the ceiling. “Maybe we go to someone with authority greater than theirs.”

“You want a spren to marry us?” she said, sounding amused. “Using a foreign priest would be heretical, but not a spren?”

“The Stormfather is the largest remnant of Honor,” Dalinar said. “He’s a sliver of the Almighty himself—and is the closest thing to a god we have left.”

“Oh, I’m not objecting,” Navani said. “I’d let a confused dishwasher marry us. I just think it’s a little unusual.”

“It’s the best we’re going to get, assuming he is willing.” He looked to Navani, then raised his eyebrows and shrugged.

“Is that a proposal?”

“…Yes?”

“Dalinar Kholin,” she said. “Surely you can do better.”

He rested his hand on the back of her head, touching her black hair, which she had left loose. “Better than you, Navani? No, I don’t think that I could. I don’t think that any man has ever had a chance better than this.”

She smiled, and her only reply was a kiss.

Dalinar was surprisingly nervous as, several hours later, he rode one of Urithiru’s strange fabrial lifts toward the roof of the tower. The lift resembled a balcony, one of many that lined a vast open shaft in the middle of Urithiru—a columnar space as wide as a ballroom, which stretched up from the first floor to the last one.

The tiers of the city, despite looking circular from the front, were actually more half-circles, with the flat sides facing east. The edges of the lower levels melded into the mountains to either side, but the very center was open to the east. The rooms up against that flat side had windows there, providing a view toward the Origin.

And here, in this central shaft, those windows made up one wall. A pure, single unbroken pane of glass hundreds of feet tall. In the day, that lit the shaft with brilliant sunlight. Now, it was dark with the gloom of night.

The balcony crawled steadily along a vertical trench in the wall; Adolin and Renarin rode with him, along with a few guards and Shallan Davar. Navani was already up above. The group stood on the other side of the balcony, giving him space to think. And to be nervous.

Why should he be nervous? He could hardly keep his hands from shaking. Storms. You’d think he was some silk-covered virgin, not a general well into his middle years.

He felt a rumbling deep within him. The Stormfather was being responsive at the moment, for which he was grateful.

“I’m surprised,” Dalinar whispered to the spren, “you agreed to this so willingly. Grateful, but still surprised.”

I respect all oaths, the Stormfather responded.

“What about foolish oaths? Made in haste, or in ignorance?”

There are no foolish oaths. All are the mark of men and true spren over beasts and subspren. The mark of intelligence, free will, and choice.

Dalinar chewed on that, and found he was not surprised by the extreme opinion. Spren should be extreme; they were forces of nature. But was this how Honor himself, the Almighty, had thought?

The balcony ground its inexorable way toward the top of the tower. Only a handful of the dozens of lifts worked; back when Urithiru flourished, they all would have been going at once. They passed level after level of unexplored space, which bothered Dalinar. Making this his fortress was like camping in an unknown land.

The lift finally reached the top floor, and his guards scrambled to open the gates. Those were from Bridge Thirteen these days—he’d assigned Bridge Four to other responsibilities, considering them too important for simple guard duty, now that they were close to becoming Radiants.

Increasingly anxious, Dalinar led the way past several pillars designed with representations of the orders of Radiants. A set of steps took him up through a trapdoor onto the very roof of the tower.

Although each tier was smaller than the one below it, this roof was still over a hundred yards wide. It was cold up here, but someone had set up braziers for warmth and torches for light. The night was strikingly clear, and high above, starspren swirled and made distant patterns.

Dalinar wasn’t sure what to make of the fact that no one—not even his sons—had questioned him when he’d announced his intent to marry in the middle of the night, on the roof of the tower. He searched out Navani, and was shocked to see that she’d found a traditional bridal crown. The intricate headdress of jade and turquoise complemented her wedding gown. Red for luck, it was embroidered with gold and shaped in a much looser style than the havah, with wide sleeves and a graceful drape.

Should Dalinar have found something more traditional to wear himself ? He suddenly felt like a dusty, empty frame hung beside the gorgeous painting that was Navani in her wedding regalia.

Elhokar stiffly stood at her side wearing a formal golden coat and loose takama underskirt. He was paler than normal, following the failed assassination attempt during the Weeping, where he’d nearly bled to death. He’d been resting a great deal lately.

Though they’d decided to forgo the extravagance of a traditional Alethi wedding, they had invited some others. Brightlord Aladar and his daughter, Sebarial and his mistress. Kalami and Teshav to act as witnesses. He felt relieved to see them there—he’d feared Navani would be unable to find women willing to notarize the wedding.

A smattering of Dalinar’s officers and scribes filled out the small procession. At the very back of the crowd gathered between the braziers, he spotted a surprising face. Kadash, the ardent, had come as requested. His scarred, bearded face didn’t look pleased, but he had come. A good sign. Perhaps with everything else happening in the world, a highprince marrying his widowed sister-in-law wouldn’t cause too much of a stir.

Dalinar stepped up to Navani and took her hands, one shrouded in a sleeve, the other warm to his touch. “You look amazing,” he said. “How did you find that?”

“A lady must be prepared.”

Dalinar looked to Elhokar, who bowed his head to Dalinar. This will further muddy the relationship between us, Dalinar thought, reading the same sentiment on his nephew’s features.

Gavilar would not appreciate how his son had been handled. Despite his best intentions, Dalinar had trodden down the boy and seized power. Elhokar’s time recuperating had worsened the situation, as Dalinar had grown accustomed to making decisions on his own.

However, Dalinar would be lying to himself if he said that was where it had begun. His actions had been done for the good of Alethkar, for the good of Roshar itself, but that didn’t deny the fact that—step by step—he’d usurped the throne, despite claiming all along he had no intention of doing so.

Dalinar let go of Navani with one hand and rested it on his nephew’s shoulder. “I’m sorry, son,” he said.

“You always are, Uncle,” Elhokar said. “It doesn’t stop you, but I don’t suppose that it should. Your life is defined by deciding what you want, then seizing it. The rest of us could learn from that, if only we could figure out how to keep up.”

Dalinar winced. “I have things to discuss with you. Plans that you might appreciate. But for tonight, I simply ask your blessing, if you can find it to give.”

“This will make my mother happy,” Elhokar said. “So, fine.” Elhokar kissed his mother on the forehead, then left them, striding across the rooftop. At first Dalinar worried the king would stalk down below, but he stopped beside one of the more distant braziers, warming his hands.

“Well,” Navani said. “The only one missing is your spren, Dalinar. If he’s going to—”

A strong breeze struck the top of the tower, carrying with it the scent of recent rainfall, of wet stone and broken branches. Navani gasped, pulling against Dalinar.

A presence emerged in the sky. The Stormfather encompassed everything, a face that stretched to both horizons, regarding the men imperiously. The air became strangely still, and everything but the tower’s top seemed to fade. It was as if they had slipped into a place outside of time itself.

Lighteyes and guards alike murmured or cried out. Even Dalinar, who had been expecting this, found himself taking a step backward—and he had to fight the urge to cringe down before the spren.

OATHS, the Stormfather rumbled, ARE THE SOUL OF RIGHTEOUSNESS. IF YOU ARE TO SURVIVE THE COMING TEMPEST, OATHS MUST GUIDE YOU..

“I am comfortable with oaths, Stormfather,” Dalinar called up to him. “As you know.”

YES. THE FIRST IN MILLENNIA TO BIND ME. Somehow, Dalinar felt the spren’s attention shifting to Navani. AND YOU. DO OATHS HOLD MEANING TO YOU?

“The right oaths,” Navani said.

AND YOUR OATH TO THIS MAN?

“I swear it to him, and to you, and any who care to listen. Dalinar Kholin is mine, and I am his.”

YOU HAVE BROKEN OATHS BEFORE

“All people have,” Navani said, unbowed. “We’re frail and foolish. This one I will not break. I vow it.”

The Stormfather seemed content with this, though it was far from a traditional Alethi wedding oath. Bondsmith? he asked.

“I swear it likewise,” Dalinar said, holding to her. “Navani Kholin is mine, and I am hers. I love her.”

SO BE IT.

Dalinar had anticipated thunder, lightning, some kind of celestial trump of victory. Instead, the timelessness ended. The breeze passed. The Stormfather vanished. All through the gathered guests, smoky blue awespren rings burst out above heads. But not Navani’s. Instead she was ringed by gloryspren, the golden lights rotating above her head. Nearby, Sebarial rubbed his temple—as if trying to understand what he’d seen. Dalinar’s new guards sagged, looking suddenly exhausted.

Adolin, being Adolin, let out a whoop. He ran over, trailing joyspren in the shape of blue leaves that hurried to keep up with him. He gave Dalinar—then Navani—enormous hugs. Renarin followed, more reserved but—judging from the wide grin on his face—equally pleased.

The next part became a blur, shaking hands, speaking words of thanks. Insisting that no gifts were needed, as they’d skipped that part of the traditional ceremony. It seemed that the Stormfather’s pronouncement had been dramatic enough that everyone accepted it. Even Elhokar, despite his earlier pique, gave his mother a hug and Dalinar a clasp on the shoulder before going below.

That left only Kadash. The ardent waited to the end. He stood with hands clasped before him as the rooftop emptied.

To Dalinar, Kadash had always looked wrong in those robes. Though he wore the traditional squared beard, it was not an ardent that Dalinar saw. It was a soldier, with a lean build, dangerous posture, and keen light violet eyes. He had a twisting old scar running up to and around the top of his shaved head. Kadash’s life might now be one of peace and service, but his youth had been spent at war.

Dalinar whispered a few words of promise to Navani, and she left him to go to the level below, where she’d ordered food and wine to be set up. Dalinar stepped over to Kadash, confident. The pleasure of having finally done what he’d postponed for so long surged through him. He was married to Navani. This was a joy that he’d assumed lost to him since his youth, an outcome he hadn’t even allowed himself to dream would be his.

He would not apologize for it, or for her.

“Brightlord,” Kadash said quietly.

“Formality, old friend?”

“I wish I could only be here as an old friend,” Kadash said softly. “I have to report this, Dalinar. The ardentia will not be pleased.”

“Surely they cannot deny my marriage if the Stormfather himself blessed the union.”

“A spren? You expect us to accept the authority of a spren?”

“A remnant of the Almighty.”

“Dalinar, that’s blasphemy,” Kadash said, voice pained. “Kadash. You know I’m no heretic. You’ve fought by my side.”

“That’s supposed to reassure me? Memories of what we did together, Dalinar? I appreciate the man you have become; you should avoid reminding me of the man you once were.”

Dalinar paused, and a memory swirled up from the depths inside him—one he hadn’t thought of in years. One that surprised him. Where had it come from?

He remembered Kadash, bloodied, kneeling on the ground having retched until his stomach was empty. A hardened soldier who had encountered something so vile that even he was shaken.

He’d left to become an ardent the next day.

“The Rift,” Dalinar whispered. “Rathalas.”

“Dark times need not be dredged up,” Kadash said. “This isn’t about… that day, Dalinar. It’s about today, and what you’ve been spreading among the scribes. Talk of these things you’ve seen in visions.”

“Holy messages,” Dalinar said, feeling cold. “Sent by the Almighty.”

“Holy messages claiming the Almighty is dead?” Kadash said. “Arriving on the eve of the return of the Voidbringers? Dalinar, can’t you see how this looks? I’m your ardent, technically your slave. And yes, perhaps still your friend. I’ve tried to explain to the councils in Kharbranth and Jah Keved that you mean well. I tell the ardents of the Holy Enclave that you’re looking back toward when the Knights Radiant were pure, rather than their eventual corruption. I tell them that you have no control over these visions.

“But Dalinar, that was before you started teaching that the Almighty was dead. They’re angry enough over that, and now you’ve gone and defied convention, spitting in the eyes of the ardents! I personally don’t think it matters if you marry Navani. That prohibition is outdated to be sure. But what you’ve done tonight…”

Dalinar reached to place a hand on Kadash’s shoulder, but the man pulled away.

“Old friend,” Dalinar said softly, “Honor might be dead, but I have felt… something else. Something beyond. A warmth and a light. It is not that God has died, it is that the Almighty was never God. He did his best to guide us, but he was an impostor. Or perhaps only an agent. A being not unlike a spren—he had the power of a god, but not the pedigree.”

Kadash looked at him, eyes widening. “Please, Dalinar. Don’t ever repeat what you just said. I think I can explain away what happened tonight. Maybe. But you don’t seem to realize you’re aboard a ship barely afloat in a storm, while you insist on doing a jig on the prow!”

“I will not hold back truth if I find it, Kadash,” Dalinar said. “You just saw that I am literally bound to a spren of oaths. I don’t dare lie.”

“I don’t think you would lie, Dalinar,” Kadash said. “But I do think you can make mistakes. Do not forget that I was there. You are not infallible.”

There? Dalinar thought as Kadash backed up, bowed, then turned and left. What does he remember that I cannot?

Dalinar watched him go. Finally, he shook his head, and went to join the midnight feast, intent on being done with it as soon as was seemly. He needed time with Navani.

His wife.

Chapter 5

Hearthstone

I can point to the moment when I decided for certain this record had to be written. I hung between realms, seeing into Shadesmar—the realm of the spren—and beyond.

—From Oathbringer, preface

Kaladin trudged through a field of quiet rockbuds, fully aware that he was too late to prevent a disaster. His failure pressed down on him with an almost physical sensation, like the weight of a bridge he was forced to carry all on his own.

After so long in the eastern part of the stormlands, he had nearly forgotten the sights of a fertile landscape. Rockbuds here grew almost as big as barrels, with vines as thick as his wrist spilling out and lapping water from the pools on the stone. Fields of vibrant green grass pulled back into burrows before him, easily three feet tall when standing at height. The field was dappled with glowing lifespren, like motes of green dust.

The grass back near the Shattered Plains had barely reached as high as his ankle, and had mostly grown in yellowish patches on the leeward side of hills. He was surprised to find that he distrusted this taller, fuller grass. An ambusher could hide in that, by crouching down and waiting for the grass to rise back up. How had Kaladin never noticed? He’d run through fields like this playing catch-me with his brother, trying to see who was quick enough to grab handfuls of grass before it hid.

Kaladin felt drained. Used up. Four days ago, he’d traveled by Oathgate to the Shattered Plains, then flown to the northwest at speed. Filled to bursting with Stormlight—and carrying a wealth more in gemstones—he’d been determined to reach his home, Hearthstone, before the Everstorm returned.

After just half a day, he’d run out of Stormlight somewhere in Aladar’s princedom. He’d been walking ever since. Perhaps he could have flown all the way to Hearthstone if he’d been more practiced with his powers. As it was, he’d traveled over a thousand miles in half a day, but this last bit—ninety or so miles—had taken an excruciating three days.

He hadn’t beaten the Everstorm. It had arrived earlier in the day around noon.

Kaladin noticed a bit of debris peeking out of the grass, and he trudged toward it. The foliage obligingly pulled back before him, revealing a broken wooden churn, the kind used for turning sow’s milk into butter. Kaladin crouched and rested fingers on the splintered wood, then glanced toward another chunk of wood peeking out over the tops of the grass.

Syl zipped down as a ribbon of light, passing his head and spinning around the length of wood.

“It’s the edge of a roof,” Kaladin said. “The lip that hangs down on the leeward side of a building.” Probably from a storage shed, judging by the other debris.

Alethkar wasn’t in the harshest of the stormlands, but neither was this some soft-skinned Western land. Buildings here were built low and squat, sturdy sides pointed eastward toward the Origin, like the shoulder of a man set and ready to take the force of an impact. Windows would only be on the leeward—the westward—side. Like the grass and the trees, humankind had learned to weather the storms.

That depended on storms always blowing in the same direction. Kaladin had done what he could to prepare the villages and towns he passed for the coming Everstorm, which would blow in the wrong direction and transform parshmen into destructive Voidbringers. Nobody in those towns had possessed working spanreeds, however, and he’d been unable to contact his home.

He hadn’t been fast enough. Earlier today, he’d spent the Everstorm within a tomb he’d hollowed out of rock using his Shardblade—Syl herself, who could manifest as any weapon he desired. In truth, the storm hadn’t been nearly as bad as the one where he’d fought the Assassin in White. But the debris he found here proved that this one had been bad enough.

The mere memory of that red storm outside his hollow made panic rise inside him. The Everstorm was so wrong, so unnatural—like a baby born with no face. Some things just should not be.

He stood up and continued on his way. He had changed uniforms before leaving—his old uniform had been bloodied and tattered. He now wore a spare generic Kholin uniform. It felt wrong not to bear the symbol of Bridge Four.

He crested a hill and spotted a river to his right. Trees sprouted along its banks, hungry for the extra water. That would be Hobble’s Brook. So if he looked directly west…

Hand shading his eyes, he could see hills that had been stripped of grass and rockbuds. They’d soon be slathered with seed-crem, and lavis polyps would start to bud. That hadn’t started yet; this was supposed to be the Weeping. Rain should be falling right now in a constant, gentle shower.

Syl zipped up in front of him, a ribbon of light. “Your eyes are brown again,” she noted.

It took a few hours without summoning his Shardblade. Once he did that, his eyes would bleed to a glassy light blue, almost glowing. Syl found the variation fascinating; Kaladin still hadn’t decided how he felt about it.

“We’re close,” Kaladin said, pointing. “Those fields belong to Hobbleken. We’re maybe two hours from Hearthstone.”

“Then you’ll be home!” Syl said, her ribbon of light spiraling and taking the shape of a young woman in a flowing havah, tight and buttoning above the waist, with safehand covered.

Kaladin grunted, walking down the slope, longing for Stormlight. Being without it now, after holding so much, was an echoing hollowness within him. Was this what it would be like every time he ran dry?

The Everstorm hadn’t recharged his spheres, of course. Neither with Stormlight nor some other energy, which he’d feared might happen.

“Do you like the new dress?” Syl asked, wagging her covered safehand as she stood in the air.

“Looks strange on you.”

“I’ll have you know I put a ton of thought into it. I spent positively hours thinking of just how—Oh! What’s that?”

She turned into a little stormcloud that shot toward a lurg clinging to a stone. She inspected the fist-size amphibian on one side, then the other, before squealing in joy and turning into a perfect imitation of the thing—except pale white-blue. This startled the creature away, and she giggled, zipping back toward Kaladin as a ribbon of light.

“What were we saying?” she asked, forming into a young woman and resting on his shoulder.

“Nothing important.”

“I’m sure I was scolding you. Oh, yes, you’re home! Yay! Aren’t you excited ?”

She didn’t see it—didn’t realize. Sometimes, for all her curiosity, she could be oblivious.

“But… it’s your home…” Syl said. She huddled down. “What’s wrong?”

“The Everstorm, Syl,” Kaladin said. “We were supposed to beat it here.” He’d needed to beat it here.

Surely someone would have survived, right? The fury of the storm, and then the worse fury after? The murderous rampage of servants turned into monsters?

Oh, Stormfather. Why hadn’t he been faster?

He forced himself into a double march again, pack slung over his shoulder. The weight was still heavy, dreadfully so, but he found that he had to know. Had to see.

Someone had to witness what had happened to his home.

The rain resumed about an hour out of Hearthstone, so at least the weather patterns hadn’t been completely ruined. Unfortunately, this meant he had to hike the rest of the way wet. He splashed through puddles where rainspren grew, blue candles with eyes on the very tip.

“It will be all right, Kaladin,” Syl promised from his shoulder. She’d created an umbrella for herself, and still wore the traditional Vorin dress instead of her usual girlish skirt. “You’ll see.”

The sky had darkened by the time he finally crested the last lavis hill and looked down on Hearthstone. He braced himself for the destruction, but it shocked him nonetheless. Some of the buildings he remembered were simply… gone. Others stood without roofs. He couldn’t see the entire town from his vantage, not in the gloom of the Weeping, but many of the structures he could make out were hollow and ruined.

He stood for a long time as night fell. He didn’t spot a glimmer of light in the town. It was empty.

Dead.

A part of him scrunched up inside, huddling into a corner, tired of being whipped so often. He’d embraced his power; he’d taken the path of a Radiant. Why hadn’t it been enough?

His eyes immediately sought out his own home on the outskirts of town. But no. Even if he’d been able to see it in the rainy evening gloom, he didn’t want to go there. Not yet. He couldn’t face the death he might find.

Instead, he rounded Hearthstone on the northwestern side, where a hill led up to the citylord’s manor. The larger rural towns like this served as a kind of hub for the small farming communities around them. Because of that, Hearthstone was cursed with the presence of a lighteyed ruler of some status. Brightlord Roshone, a man whose greedy ways had ruined far more than one life.

Moash… Kaladin thought as he trudged up the hill toward the manor, shivering in the chill and the darkness. He’d have to face his friend’s betrayal—and near assassination of Elhokar—at some point. For now, he had more pressing wounds that needed tending.

The manor was where the town’s parshmen had been kept; they’d have begun their rampage here. He was pretty sure that if he ran across Roshone’s broken corpse, he wouldn’t be too heartbroken.

“Wow,” Syl said. “Gloomspren.”

Kaladin looked up and noted an unusual spren whipping about. Long, grey, like a tattered streamer of cloth in the wind. It wound around him, fluttering. He’d seen its like only once or twice before.

“Why are they so rare?” Kaladin asked. “People feel gloomy all the time.”

“Who knows?” Syl said. “Some spren are common. Some are uncommon.” She tapped his shoulder. “I’m pretty sure one of my aunts liked to hunt these things.”

“Hunt them?” Kaladin asked. “Like, try to spot them?”

“No. Like you hunt greatshells. Can’t remember her name…” Syl cocked her head, oblivious to the fact that rain was falling through her form. “She wasn’t really my aunt. Just an honorspren I referred to that way. What an odd memory.”

“More seems to be coming back to you.”

“The longer I’m with you, the more it happens. Assuming you don’t try to kill me again.” She gave him a sideways look. Though it was dark, she glowed enough for him to make out the expression.

“How often are you going to make me apologize for that?”

“How many times have I done it so far?”

“At least fifty.”

“Liar,” Syl said. “Can’t be more than twenty.”

“I’m sorry.”

Wait. Was that light up ahead?

Kaladin stopped on the path. It was light, coming from the manor house. It flickered unevenly. Fire? Was the manor burning? No, it seemed to be candles or lanterns inside. Someone, it appeared, had survived. Humans or Voidbringers?

He needed to be careful, though as he approached, he found that he didn’t want to be. He wanted to be reckless, angry, destructive. If he found the creatures that had taken his home from him…

“Be ready,” he mumbled to Syl.

He stepped off the pathway, which was kept free of rockbuds and other plants, and crept carefully toward the manor. Light shone between boards that had been pounded across the building’s windows, replacing glass that the Everstorm undoubtedly broke. He was surprised the manor had survived as well as it had. The porch had been ripped free, but the roof remained.

The rain masked other sounds and made it difficult to see much beyond that, but someone, or something, was inside. Shadows moved in front of the lights.

Heart pounding, Kaladin rounded toward the northern side of the building. The servants’ entrance would be here, along with the quarters for the parshmen. An unusual amount of noise came from inside the manor house. Thumping. Motion. Like a nest full of rats.

He had to feel his way through the gardens. The parshmen had been housed in a small structure built in the manor’s shadow, with a single open chamber and benches for sleeping. Kaladin reached it by touch and felt at a large hole ripped in the side.

Scraping came from behind him.

Kaladin spun as the back door of the manor opened, its warped frame grinding against stone. He dove for cover behind a shalebark mound, but light bathed him, cutting through the rain. A lantern.

Kaladin stretched his hand to the side, prepared to summon Syl, yet the person who stepped from the manor was no Voidbringer, but instead a human guardsman in an old helm spotted by rust.

The man held up his lantern. “Here now,” he shouted at Kaladin, fumbling at the mace on his belt. “Here now! You there!” He pulled free the weapon and held it out in a quivering hand. “What are you? Deserter? Come here into the light and let me see you.”

Kaladin stood up warily. He didn’t recognize the soldier—but either someone had survived the Voidbringer assault, or this man was part of an expedition investigating the aftermath. Either way, it was the first hopeful sign Kaladin had seen since arriving.

He held his hands up—he was unarmed save for Syl—and let the guard bully him into the building.

Chapter 6

Four Lifetimes

I thought that I was surely dead. Certainly, some who saw further than I did thought I had fallen.

—From Oathbringer, preface

Kaladin stepped into Roshone’s manor, and his apocalyptic visions of death and loss started to fade as he recognized people. He passed Toravi, one of the town’s many farmers, in the hallway. Kaladin remembered the man as being enormous, with thick shoulders. In actuality, he was shorter than Kaladin by half a hand, and most of Bridge Four could have outmatched him for muscles.

Toravi didn’t seem to recognize Kaladin. The man stepped into a side chamber, which was packed with darkeyes sitting on the floor.

The soldier walked Kaladin along the candlelit hallway. They passed through the kitchens, and Kaladin noted dozens of other familiar faces. The townspeople filled the manor, packing every room. Most sat on the floor in family groups, and while they looked tired and disheveled, they were alive. Had they rebuffed the Voidbringer assault, then?

My parents, Kaladin thought, pushing through a small group of townspeople and moving more quickly. Where were his parents?

“Whoa, there!” said the soldier behind, grabbing Kaladin by the shoulder. He shoved his mace into the small of Kaladin’s back. “Don’t make me down you, son.”

Kaladin turned on the guardsman, a clean-shaven fellow with brown eyes that seemed set a little too close together. That rusted cap was a disgrace.

“Now,” the soldier said, “we’re just going to go find Brightlord Roshone, and you’re going to explain why you were skulking round the place. Act real nice, and maybe he won’t hang you. Understand?”

The townspeople in the kitchens noticed Kaladin finally, and pulled away. Many whispered to one another, eyes wide, fearful. He heard the words “deserter,” “slave brands,” “dangerous.”

Nobody said his name.

“They don’t recognize you?” Syl asked as she walked across a kitchen countertop.

Why would they recognize this man he had become? Kaladin saw himself reflected in a pan hanging beside the brick oven. Long hair with a curl to it, the tips resting against his shoulders. A rough uniform that was a shade too small for him, face bearing a scruffy beard from several weeks without shaving. Soaked and exhausted, he looked like a vagabond.

This wasn’t the homecoming he’d imagined during his first months at war. A glorious reunion where he returned as a hero wearing the knots of a sergeant, his brother delivered safe to his family. In his fancies, people had praised him, slapped him on the back and accepted him.

Idiocy. These people had never treated him or his family with any measure of kindness.

“Let’s go,” the soldier said, shoving him on the shoulder.

Kaladin didn’t move. When the man shoved harder, Kaladin rolled his body with the push, and the shift of weight sent the guard stumbling past him. The man turned, angry. Kaladin met his gaze. The guard hesitated, then took a step back and gripped his mace more firmly.

“Wow,” Syl said, zipping up to Kaladin’s shoulder. “That is quite the glare

you gave.”

“Old sergeant’s trick,” Kaladin whispered, turning and leaving the kitchens. The guard followed behind, barking an order that Kaladin ignored.

Each step through this manor was like walking through a memory. There was the dining nook where he’d confronted Rillir and Laral on the night he’d discovered his father was a thief. This hallway beyond, hung with portraits of people he didn’t know, had been where he’d played as a child. Roshone hadn’t changed the portraits.

He’d have to talk to his parents about Tien. It was why he hadn’t tried to contact them after being freed from slavery. Could he face them? Storms, he hoped they lived. But could he face them?

He heard a moan. Soft, underneath the sounds of people talking, still he picked it out.

“There were wounded?” he asked, turning on his guard.

“Yeah,” the man said. “But—”

Kaladin ignored him and strode down the hallway, Syl flying along beside his head. Kaladin shoved past people, following the sounds of the tormented, and eventually stumbled into the doorway of the parlor. It had been transformed into a surgeon’s triage room, with mats laid out on the floor bearing wounded.

A figure knelt by one of the pallets carefully splinting a broken arm. Kaladin had known as soon as he’d heard those moans of pain where he’d find his father.

Lirin glanced at him. Storms. Kaladin’s father looked weathered, bags underneath his dark brown eyes. The hair was greyer than Kaladin remembered, the face gaunter. But he was the same. Balding, diminutive, thin, bespectacled… and amazing.

“What’s this?” Lirin asked, turning back to his work. “Did the highprince’s house send soldiers already? That was faster than expected. How many did you bring? We can certainly use…” Lirin hesitated, then looked back at Kaladin.

Then his eyes opened wide.

“Hello, Father,” Kaladin said.

The guardsman finally caught up, shouldering past gawking townspeople and waving his mace toward Kaladin like a baton. Kaladin sidestepped absently, then pushed the man so he stumbled farther down the hallway.

“It is you,” Lirin said. Then he scrambled over and caught Kaladin in an embrace. “Oh, Kal. My boy. My little boy. Hesina! HESINA!”

Kaladin’s mother appeared in the doorway a moment later, bearing a tray of freshly boiled bandages. She probably thought that Lirin needed her help with a patient. Taller than her husband by a few fingers, she wore her hair tied back with a kerchief just as Kaladin remembered.

She raised her gloved safehand to her lips, gaping, and the tray slipped down in her other hand, tumbling bandages to the floor. Shockspren, like pale yellow triangles breaking and re-forming, appeared behind her. She dropped the tray and reached to the side of Kaladin’s face with a soft touch. Syl zipped around in a ribbon of light, laughing.

Kaladin couldn’t laugh. Not until it had been said. He took a deep breath, choked on it the first time, then finally forced it out.

“I’m sorry, Father, Mother,” he whispered. “I joined the army to protect him, but I could barely protect myself.” He found himself shaking, and he put his back to the wall, letting himself sink down until he was seated. “I let Tien die. I’m sorry. It’s my fault.…”

“Oh, Kaladin,” Hesina said, kneeling down beside him and pulling him into an embrace. “We got your letter, but over a year ago they told us you had died as well.”

“I should have saved him,” Kaladin whispered.

“You shouldn’t have gone in the first place,” Lirin said. “But now… Almighty, now you’re back.” Lirin stood up, tears leaking down his cheeks. “My son! My son is alive!”

A short time later, Kaladin sat among the wounded, holding a cup of warm soup in his hands. He hadn’t had a hot meal since… when?

“That’s obviously a slave’s brand, Lirin,” a soldier said, speaking with Kaladin’s father near the doorway into the room. “Sas glyph, so it happened here in the princedom. They probably told you he’d died to save you the shame of the truth. And then the shash brand—you don’t get that for mere insubordination.”

Kaladin sipped his soup. His mother knelt beside him, one hand on his shoulder, protective. The soup tasted of home. Boiled vegetable broth with steamed lavis stirred in, spiced as his mother always made it.

He hadn’t spoken much in the half hour since he’d arrived. For now, he just wanted to be here with them.

Strangely, his memories had turned fond. He remembered Tien laughing, brightening the dreariest of days. He remembered hours spent studying medicine with his father, or cleaning with his mother.

Syl hovered before his mother, still wearing her little havah, invisible to everyone but Kaladin. The spren had a perplexed look on her face.

“The wrong-way highstorm did break many of the town’s buildings,” Hesina explained to him softly. “But our home still stands. We had to dedicate your spot to something else, Kal, but we can make space for you.”

Kaladin glanced at the soldier. Captain of Roshone’s guard; Kaladin thought he remembered the man. He almost seemed too pretty to be a soldier, but then, he was lighteyed.

“Don’t worry about that,” Hesina said. “We’ll deal with it, whatever the… trouble is. With all these wounded pouring in from the villages around, Roshone will need your father’s skill. Roshone won’t go making a storm and risk Lirin’s discontent—and you won’t be taken from us again.”

She talked to him as if he were a child.

What a surreal sensation, being back here, being treated like he was still the boy who had left for war five years ago. Three men bearing their son’s name had lived and died in that time. The soldier who had been forged in Amaram’s army. The slave, so bitter and angry. His parents had never met Captain Kaladin, bodyguard to the most powerful man in Roshar.

And then… there was the next man, the man he was becoming. A man who owned the skies and spoke ancient oaths. Five years had passed. And four lifetimes.

“He’s a runaway slave,” the guard captain hissed. “We can’t just ignore that, surgeon. He probably stole the uniform. And even if for some reason he was allowed to hold a spear despite his brands, he’s a deserter. Look at those haunted eyes and tell me you don’t see a man who has done terrible things.”

“He’s my son,” Lirin said. “I’ll buy his writ of slavery. You’re not taking him. Tell Roshone he can either let this slide, or he can go without a surgeon. Unless he assumes Mara can take over after just a few years of apprenticeship.”

Did they think they were speaking softly enough that he couldn’t hear?

Look at the wounded people in this room, Kaladin. You’re missing something.

The wounded… they displayed fractures. Concussions. Very few lacerations. This was not the aftermath of a battle, but of a natural disaster. So what had happened to the Voidbringers? Who had fought them off ?

“Things have gotten better since you left,” Hesina promised Kaladin, squeezing his shoulder. “Roshone isn’t as bad as he once was. I think he feels guilty. We can rebuild, be a family again. And there’s something else you need to know about. We—”

“Hesina,” Lirin said, throwing his hands into the air.

“Yes?”

“Write a letter to the highprince’s administrators,” Lirin said. “Explain the situation; see if we can get a forbearance, or at least an explanation.” He looked to the soldier. “Will that satisfy your master? We can wait upon a higher authority, and in the meantime I can have my son back.”

“We’ll see,” the soldier said, folding his arms. “I’m not sure how much I like the idea of a shash-branded man running around my town.”

Hesina rose to join Lirin. The two had a hushed exchange as the guard settled back against the doorway, pointedly keeping an eye on Kaladin. Did he know how little like a soldier he looked? He didn’t walk like a man acquainted with battle. He stepped too hard, and stood with his knees too straight. There were no dents in his breastplate, and his sword’s scabbard knocked against things as he turned.

Kaladin sipped his soup. Was it any wonder that his parents still thought of him as a child? He’d come in looking ragged and abandoned, then had started sobbing about Tien’s death. Being home brought out the child in him, it seemed.

Perhaps it was time, for once, to stop letting the rain dictate his mood. He couldn’t banish the seed of darkness inside him, but Stormfather, he didn’t need to let it rule him either.

Syl walked up to him in the air. “They’re like I remember them.” “Remember them?” Kaladin whispered. “Syl, you never knew me when

I lived here.”

“That’s true,” she said.

“So how can you remember them?” Kaladin said, frowning.

“Because I do,” Syl said, flitting around him. “Everyone is connected, Kaladin. Everything is connected. I didn’t know you then, but the winds did, and I am of the winds.”

“You’re honorspren.”

“The winds are of Honor,” she said, laughing as if he’d said something ridiculous. “We are kindred blood.”

“You don’t have blood.”

“And you don’t have an imagination, it appears.” She landed in the air before him and became a young woman. “Besides, there was… another voice. Pure, with a song like tapped crystal, distant yet demanding…” She smiled, and zipped away.

Well, the world might have been upended, but Syl was as impenetrable as ever. Kaladin set aside his soup and climbed to his feet. He stretched to one side, then the other, feeling satisfying pops from his joints. He walked toward his parents. Storms, but everyone in this town seemed smaller than he remembered. He hadn’t been that much shorter when he’d left Hearthstone, had he?

A figure stood right outside the room, speaking with the guard with the rusty helmet. Roshone wore a lighteyes’ coat that was several seasons out of fashion—Adolin would have shaken his head at that. The citylord wore a wooden foot on his right leg, and had lost weight since Kaladin had last seen him. His skin drooped on his figure like melted wax, bunching up at his neck.

That said, Roshone had the same imperious bearing, the same angry expression—his light yellow eyes seemed to blame everyone and everything in this insignificant town for his banishment. He’d once lived in Kholinar, but had been involved in the deaths of some citizens—Moash’s grandparents—and had been shipped out here as punishment.

He turned toward Kaladin, lit by candles on the walls. “So, you’re alive. They didn’t teach you to keep yourself in the army, I see. Let me have a look at those brands of yours.” He reached over and held up the hair in front of Kaladin’s forehead. “Storms, boy. What did you do? Hit a lighteyes?”

“Yes,” Kaladin said. Then punched him.

He bashed Roshone right in the face. A solid hit, exactly like Hav had taught him. Thumb outside of his fist, he connected with the first two knuckles of his hand across Roshone’s cheekbone, then followed through to slide across the front of the face. Rarely had he delivered such a perfect punch. It barely even hurt his fist.

Roshone dropped like a felled tree.

“That,” Kaladin said, “was for my friend Moash.”

Oathbringer: The Stormlight Archive Book 3 copyright © 2017 Dragonsteel Entertainment, LLC