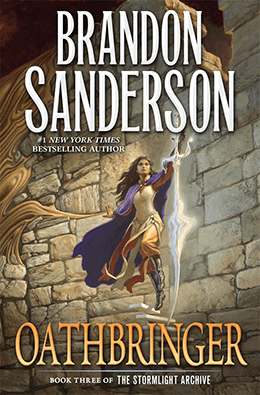

Start reading Oathbringer, the new volume of Brandon Sanderson’s Stormlight Archive epic, right now. For free!

Tor.com is serializing the much-awaited third volume in the Stormlight Archive series every Tuesday until the novel’s November 14, 2017 release date.

Every installment is collected here in the Oathbringer index.

Need a refresher on the Stormlight Archive before beginning Oathbringer? Here’s a summary of what happened in Book 1: The Way of Kings and Book 2: Words of Radiance.

Spoiler warning: Comments will contain spoilers for previous Stormlight books, other works that take place in Sanderson’s cosmere (Elantris, Mistborn, Warbreaker, etc.), and the available chapters of Oathbringer, along with speculation regarding the chapters yet to come.

Chapter 7

A Watcher at the Rim

I did not die.

I experienced something worse.

—From Oathbringer, preface

“Kaladin!” Lirin exclaimed, grabbing him by the shoulder. “What are you doing, son?”

Roshone sputtered on the ground, his nose bleeding. “Guards, take him! You hear me!”

Syl landed on Kaladin’s shoulder, hands on her hips. She tapped her foot. “He probably deserved that.”

The darkeyed guard scrambled to help Roshone to his feet while the captain leveled his sword at Kaladin. A third joined them, running in from another room.

Kaladin stepped one foot back, falling into a guard position.

“Well?” Roshone demanded, holding his handkerchief to his nose. “Strike him down!” Angerspren boiled up from the ground in pools.

“Please, no,” Kaladin’s mother cried, clinging to Lirin. “He’s just distraught. He—”

Kaladin held out a hand toward her, palm forward, in a quieting motion. “It’s all right, Mother. That was only payment for a little unsettled debt between Roshone and me.”

He met the eyes of the guards, each in turn, and they shuffled uncertainly. Roshone blustered. Unexpectedly, Kaladin felt in complete control of the situation—and… well, more than a little embarrassed.

Suddenly, the perspective of it crashed down on him. Since leaving Hearthstone, Kaladin had met true evil, and Roshone hardly compared. Hadn’t he sworn to protect even those he didn’t like? Wasn’t the whole point of what he had learned to keep him from doing things like this? He glanced at Syl, and she nodded to him.

Do better.

For a short time, it had been nice to just be Kal again. Fortunately, he wasn’t that youth any longer. He was a new person—and for the first time in a long, long while, he was happy with that person.

“Stand down, men,” Kaladin said to the soldiers. “I promise not to hit your brightlord again. I apologize for that; I was momentarily distracted by our previous history. Something he and I both need to forget. Tell me, what happened to the parshmen? Did they not attack the town?”

The soldiers shifted, glancing toward Roshone.

“I said stand down,” Kaladin snapped. “For storm’s sake, man. You’re holding that sword like you’re going to chop a stumpweight. And you? Rust on your cap? I know Amaram recruited most of the able-bodied men in the region, but I’ve seen messenger boys with more battle poise than you.”

The soldiers looked to one another. Then, red-faced, the lighteyed one slid his sword back into its sheath.

“What are you doing?” Roshone demanded. “Attack him!”

“Brightlord, sir,” the man said, eyes down. “I may not be the best soldier around, but… well, sir, trust me on this. We should just pretend that punch never happened.” The other two soldiers nodded their heads in agreement.

Roshone sized Kaladin up, dabbing at his nose, which wasn’t bleeding badly. “So, they did make something out of you in the army, did they?”

“You have no idea. We need to talk. Is there a room here that isn’t clogged full of people?”

“Kal,” Lirin said. “You’re speaking foolishness. Don’t give orders to Brightlord Roshone!”

Kaladin pushed past the soldiers and Roshone, walking farther down the hallway. “Well?” he barked. “Empty room?”

“Up the stairs, sir,” one of the soldiers said. “Library is empty.”

“Excellent.” Kaladin smiled to himself, noting the “sir.” “Join me up there, men.”

Kaladin started toward the stairs. Unfortunately, an authoritative bearing could only take a man so far. Nobody followed, not even his parents.

“I gave you people an order,” Kaladin said. “I’m not fond of repeating myself.”

“And what,” Roshone said, “makes you think you can order anyone around, boy?”

Kaladin turned back and swept his arm before him, summoning Syl. A bright, dew-covered Shardblade formed from mist into his hand. He spun the Blade and rammed her down into the floor in one smooth motion. He held the grip, feeling his eyes bleed to blue.

Everything grew still. Townspeople froze, gaping. Roshone’s eyes bulged. Curiously, Kaladin’s father just lowered his head and closed his eyes.

“Any other questions?” Kaladin asked.

“They were gone when we went back to check on them, um, Brightlord,” said Aric, the short guard with the rusty helm. “We’d locked the door, but the side was ripped clean open.”

“They didn’t attack a soul?” Kaladin asked.

“No, Brightlord.”

Kaladin paced through the library. The room was small, but neatly organized with rows of shelves and a fine reading stand. Each book was exactly flush with the others; either the maids were extremely meticulous, or the books were not often moved. Syl perched on one shelf, her back to a book, swinging her legs girlishly over the edge.

Roshone sat on one side of the room, periodically pushing both hands along his flushed cheeks toward the back of his head in an odd nervous gesture. His nose had stopped bleeding, though he’d have a nice bruise. That was a fraction of the punishment the man deserved, but Kaladin found he had no passion for abusing Roshone. He had to be better than that.

“What did the parshmen look like?” Kaladin asked of the guardsmen. “They changed, following the unusual storm?”

“Sure did,” Aric said. “I peeked when I heard them break out, after the storm passed. They looked like Voidbringers, I tell you, with big bony bits jutting from their skin.”

“They were taller,” the guard captain added. “Taller than me, easily as tall as you are, Brightlord. With legs thick as stumpweights and hands that could have strangled a whitespine, I tell you.”

“Then why didn’t they attack?” Kaladin asked. They could have easily taken the manor; instead, they’d run off into the night. It spoke of a more disturbing goal. Perhaps Hearthstone was too small to be bothered with.

“I don’t suppose you tracked their direction?” Kaladin said, looking toward the guards, then Roshone.

“Um, no, Brightlord,” the captain said. “Honestly, we were just worried about surviving.”

“Will you tell the king?” Aric asked. “That storm ripped away four of our silos. We’ll be starving afore too long, with all these refugees and no food. When the highstorms start coming again, we won’t have half as many homes as we need.”

“I’ll tell Elhokar.” But Stormfather, the rest of the kingdom would be just as bad.

He needed to focus on the Voidbringers. He couldn’t report back to Dalinar until he had the Stormlight to fly home, so for now it seemed his most useful task would be to find out where the enemy was gathering, if he could. What were the Voidbringers planning? Kaladin hadn’t experienced their strange powers himself, though he’d heard reports of the Battle of Narak. Parshendi with glowing eyes and lightning at their command, ruthless and terrible.

“I’ll need maps,” he said. “Maps of Alethkar, as detailed as you have, and some way to carry them through the rain without ruining them.” He grimaced. “And a horse. Several of them, the finest you have.”

“So you’re robbing me now?” Roshone asked softly, staring at the floor.

“Robbing?” Kaladin said. “We’ll call it renting instead.” He pulled a handful of spheres from his pocket and dropped them on the table. He glanced toward the soldiers. “Well? Maps? Surely Roshone keeps survey maps of the nearby areas.”

Roshone was not important enough to have stewardship over any of the highprince’s lands—a distinction Kaladin had never realized while he lived in Hearthstone. Those lands would be watched over by much more important lighteyes; Roshone would only be a first point of contact with surrounding villages.

“We’ll want to wait for the lady’s permission,” the guard captain said. “Sir.”

Kaladin raised an eyebrow. They’d disobey Roshone for him, but not the manor’s lady? “Go to the house ardents and tell them to prepare the things I request. Permission will be forthcoming. And locate a spanreed connected to Tashikk, if any of the ardents have one. Once I have the Stormlight to use it, I’ll want to send word to Dalinar.”

The guards saluted and left.

Kaladin folded his arms. “Roshone, I’m going to need to chase those parshmen and see if I can figure out what they’re up to. I don’t suppose any of your guards have tracking experience? Following the creatures would be hard enough without the rain swamping everything.”

“Why do they matter so much?” Roshone asked, still staring at the floor.

“Surely you’ve guessed,” Kaladin said, nodding to Syl as her ribbon of light flitted over to his shoulder. “Weather in turmoil and terrors transformed from common servants? That storm with the red lightning, blowing the wrong direction? The Desolation is here, Roshone. The Voidbringers have returned.”

Roshone groaned, leaning forward, arms wrapped around himself as if he were going to be sick.

“Syl?” Kaladin whispered. “I might need you again.” “You sound apologetic,” she replied, cocking her head.

“I am. I don’t like the idea of swinging you about, smashing you into things.”

She sniffed. “Firstly, I don’t smash into things. I am an elegant and graceful weapon, stupid. Secondly, why would you be bothered?”

“It doesn’t feel right,” Kaladin replied, still whispering. “You’re a woman, not a weapon.”

“Wait… so this is about me being a girl?”

“No,” Kaladin said immediately, then hesitated. “Maybe. It just feels strange.”

She sniffed. “You don’t ask your other weapons how they feel about being swung about.”

“My other weapons aren’t people.” He hesitated. “Are they?”

She looked at him with head cocked and eyebrows raised, as if he’d said something very stupid.

Everything has a spren. His mother had taught him that from an early age.

“So… some of my spears have been women, then?” he asked.

“Female, at least,” Syl said. “Roughly half, as these things tend to go.” She flitted up into the air in front of him. “It’s your fault for personifying us, so no complaining. Of course, some of the old spren have four genders instead of two.”

“What? Why?”

She poked him in the nose. “Because humans didn’t imagine those ones, silly.” She zipped out in front of him, changing into a field of mist. When he raised his hand, the Shardblade appeared.

He strode to where Roshone sat, then stooped down and held the Shardblade before the man, point toward the floor.

Roshone looked up, transfixed by the weapon’s blade, as Kaladin had anticipated. You couldn’t be near one of these things and not be drawn by it. They had a magnetism.

“How did you get it?” Roshone asked.

“Does it matter?”

He didn’t reply, but they both knew the truth. Owning a Shardblade was enough—if you could claim it, and not have it taken from you, it was yours. With one in his possession, the brands on his head were meaningless. No man, not even Roshone, would imply otherwise.

“You,” Kaladin said, “are a cheat, a rat, and a murderer. But as much as I hate it, we don’t have time to oust Alethkar’s ruling class and set up something better. We are under attack by an enemy we do not understand, and which we could not have anticipated. So you’re going to have to stand up and lead these people.”

Roshone stared at the blade, looking at his reflection.

“We’re not powerless,” Kaladin said. “We can and will fight back—but first we need to survive. The Everstorm will return. Regularly, though I don’t know the interval yet. I need you to prepare.”

“How?” Roshone whispered.

“Build homes with slopes in both directions. If there’s not time for that, find a sheltered location and hunker down. I can’t stay. This crisis is bigger than one town, one people, even if it’s my town and my people. I have to rely on you. Almighty preserve us, you’re all we have.”

Roshone slumped down farther in his seat. Great. Kaladin stood and dismissed Syl.

“We’ll do it,” a voice said from behind him.

Kaladin froze. Laral’s voice sent a shiver down his spine. He turned slowly, and found a woman who did not at all match the image in his head. When he’d last seen her, she’d been wearing a perfect lighteyed dress, beautiful and young, yet her pale green eyes had seemed hollow. She’d lost her betrothed, Roshone’s son, and had instead become engaged to the father—a man more than twice her age.

The woman he confronted was no longer a youth. Her face was firm, lean, and her hair was pulled back in a no-nonsense tail of black peppered with blonde. She wore boots and a utilitarian havah, damp from the rain.

She looked him up and down, then sniffed. “Looks like you went and grew up, Kal. I was sorry to hear the news of your brother. Come now. You need a spanreed? I’ve got one to the queen regent in Kholinar, but that one hasn’t been responsive lately. Fortunately, we do have one to Tashikk, as you asked about. If you think that the king will respond to you, we can go through an intermediary.”

She walked back out the doorway.

“Laral…” he said, following.

“I hear you stabbed my floor,” she noted. “That’s good hardwood, I’ll have you know. Honestly. Men and their weapons.”

“I dreamed of coming back,” Kaladin said, stopping in the hallway outside the library. “I imagined returning here a war hero and challenging Roshone. I wanted to save you, Laral.”

“Oh?” She turned back to him. “And what made you think I needed saving?”

“You can’t tell me,” Kaladin said softly, waving backward toward the library, “that you’ve been happy with that.”

“Becoming a lighteyes does not grant a man any measure of decorum, it appears,” Laral said. “You will stop insulting my husband, Kaladin. Shardbearer or not, another word like that, and I’ll have you thrown from my home.”

“Laral—”

“I am quite happy here. Or I was, until the winds started blowing the wrong direction.” She shook her head. “You take after your father. Always feeling like you need to save everyone, even those who would rather you mind your own business.”

“Roshone brutalized my family. He sent my brother to his death and did everything he could to destroy my father!”

“And your father spoke against my husband,” Laral said, “disparaging him in front of the other townspeople. How would you feel, as a new brightlord exiled far from home, only to find that the town’s most important citizen is openly critical of you?”

Her perspective was skewed, of course. Lirin had tried to befriend Roshone at first, hadn’t he? Still, Kaladin found little passion to continue the argument. What did he care? He intended to see his parents moved from this city anyway.

“I’ll go set up the spanreed,” she said. “It might take some time to get a reply. In the meantime, the ardents should be fetching your maps.”

“Great,” Kaladin said, pushing past her in the hallway. “I’m going to go speak with my parents.”

Syl zipped over his shoulder as he started down the steps. “So, that’s the girl you were going to marry.”

“No,” Kaladin whispered. “That’s a girl I was never going to marry, no matter what happened.”

“I like her.”

“You would.” He reached the bottom of the steps and looked back up. Roshone had joined Laral at the top of the stairs, carrying the gems Kaladin had left on the table. How much had that been?

Five or six ruby broams, he thought, and maybe a sapphire or two. He did the calculations in his head. Storms… That was a ridiculous sum— more money than the goblet full of spheres that Roshone and Kaladin’s father had spent years fighting over back in the day. That was now mere pocket change to Kaladin.

He’d always thought of all lighteyes as rich, but a minor brightlord in an insignificant town… well, Roshone was actually poor, just a different kind of poor.

Kaladin searched back through the house, passing people he’d once known—people who now whispered “Shardbearer” and got out of his way with alacrity. So be it. He’d accepted his place the moment he’d seized Syl from the air and spoken the Words.

Lirin was back in the parlor, working on the wounded again. Kaladin stopped in the doorway, then sighed and knelt beside Lirin. As the man reached toward his tray of tools, Kaladin picked it up and held it at the ready. His old position as his father’s surgery assistant. The new apprentice was helping with wounded in another room.

Lirin eyed Kaladin, then turned back to the patient, a young boy who had a bloodied bandage around his arm. “Scissors,” Lirin said.

Kaladin proffered them, and Lirin took the tool without looking, then carefully cut the bandage free. A jagged length of wood had speared the boy’s arm. He whimpered as Lirin palpated the flesh nearby, covered in dried blood. It didn’t look good.

“Cut out the shaft,” Kaladin said, “and the necrotic flesh. Cauterize.”

“A little extreme, don’t you think?” Lirin asked.

“Might want to remove it at the elbow anyway. That’s going to get infected for sure—look how dirty that wood is. It will leave splinters.”

The boy whimpered again. Lirin patted him. “You’ll be fine. I don’t see any rotspren yet, and so we’re not going to take the arm off. Let me talk to your parents. For now, chew on this.” He gave the boy some bark as a relaxant.

Together, Lirin and Kaladin moved on; the boy wasn’t in immediate danger, and Lirin would want to operate after the anesthetic took effect.

“You’ve hardened,” Lirin said to Kaladin as he inspected the next patient’s foot. “I was worried you’d never grow calluses.”

Kaladin didn’t reply. In truth, his calluses weren’t as deep as his father might have wanted.

“But you’ve also become one of them,” Lirin said.

“My eye color doesn’t change a thing.”

“I wasn’t speaking of your eye color, son. I don’t give two chips whether a man is lighteyed or not.” He waved a hand, and Kaladin passed him a rag to clean the toe, then started preparing a small splint.

“What you’ve become,” Lirin continued, “is a killer. You solve problems with the fist and the sword. I had hoped that you would find a place among the army’s surgeons.”

“I wasn’t given much choice,” Kaladin said, handing over the splint, then preparing some bandages to wrap the toe. “It’s a long story. I’ll tell you sometime.” The less soul-crushing parts of it, at least.

“I don’t suppose you’re going to stay.”

“No. I need to follow those parshmen.”

“More killing, then.”

“And you honestly think we shouldn’t fight the Voidbringers, Father?”

Lirin hesitated. “No,” he whispered. “I know that war is inevitable. I just didn’t want you to have to be a part of it. I’ve seen what it does to men. War flays their souls, and those are wounds I can’t heal.” He secured the splint, then turned to Kaladin. “We’re surgeons. Let others rend and break; we must not harm others.”

“No,” Kaladin said. “You’re a surgeon, Father, but I’m something else. A watcher at the rim.” Words spoken to Dalinar Kholin in a vision. Kaladin stood up. “I will protect those who need it. Today, that means hunting down some Voidbringers.”

Lirin looked away. “Very well. I am… glad you returned, son. I’m glad you’re safe.”

Kaladin rested his hand on his father’s shoulder. “Life before death, Father.”

“See your mother before you leave,” Lirin said. “She has something to show you.”

Kaladin frowned, but made his way out of the healing chamber to the kitchens. The entire place was lit only by candles, and not many of them. Everywhere he went, he saw shadows and uncertain light.

He filled his canteen with fresh water and found a small umbrella. He’d need that for reading maps in this rain. From there, he went hiking up to check on Laral in the library. Roshone had retreated to his room, but she was sitting at a writing table with a spanreed before her.

Wait. The spanreed was working. Its ruby glowed.

“Stormlight!” Kaladin said, pointing.

“Well, of course,” she said, frowning at him. “Fabrials require it.”

“How do you have infused spheres?”

“The highstorm,” Laral said. “Just a few days back.”

During the clash with the Voidbringers, the Stormfather had summoned an irregular highstorm to match the Everstorm. Kaladin had flown before its stormwall, fighting the Assassin in White.

“That storm was unexpected,” Kaladin said. “How in the world did you know to leave your spheres out?”

“Kal,” she said, “it’s not so hard to hang some spheres out once a storm starts blowing!”

“How many do you have?”

“Some,” Laral said. “The ardents have a few—I wasn’t the only one to think of it. Look, I’ve got someone in Tashikk willing to relay a message to Navani Kholin, the king’s mother. Wasn’t that what you implied you wanted? You really think she’ll respond to you?”

The answer, blessedly, came as the spanreed started writing. “ ‘Captain?’ ” Laral read. “ ‘This is Navani Kholin. Is it really you?’ ”

Laral blinked, then looked up at him.

“It is,” Kaladin said. “The last thing I did before leaving was speak with Dalinar at the top of the tower.” Hopefully that would be enough to authenticate him.

Laral jumped, then wrote it.

“ ‘Kaladin, this is Dalinar,’” Laral read as the message came back. “ ‘What is your status, soldier?’ ”

“Better than expected, sir,” Kaladin said. He outlined what he’d discovered, in brief. He ended by noting, “I’m worried that they left because Hearthstone wasn’t important enough to bother destroying. I’ve ordered horses and some maps. I figure I can do a little scouting and see what I can find about the enemy.”

“ ‘Careful,’ ” Dalinar responded. “ ‘You don’t have any Stormlight left?’ ”

“I might be able to find a little. I doubt it will be enough to get me home, but it will help.”

It took a few minutes before Dalinar replied, and Laral took the opportunity to change the paper on the spanreed board.

“ ‘Your instincts are good, Captain,’ ” Dalinar finally sent. “ ‘I feel blind in this tower. Get close enough to discover what the enemy is doing, but don’t take unnecessary risks. Take the spanreed. Send us a glyph each evening to know you are safe.’ ”

“Understood, sir. Life before death.”

“ ‘Life before death.’ ”

Laral looked to him, and he nodded that the conversation was over. She packed up the spanreed for him without a word, and he took it gratefully, then hurried out of the room and down the steps.

His activities had drawn quite a crowd of people, who had gathered in the small entry hall before the steps. He intended to ask if anyone had infused spheres, but was interrupted by the sight of his mother. She was speaking with several young girls, and held a toddler in her arms. What was she doing with…

Kaladin stopped at the foot of the steps. The little boy was perhaps a year old, chewing on his hand and babbling around his fingers.

“Kaladin, meet your brother,” Hesina said, turning toward him. “Some of the girls were watching him while I helped with the triage.”

“A brother,” Kaladin whispered. It had never occurred to him. His mother would be forty-one this year, and…

A brother.

Kaladin reached out. His mother let him take the little boy, hold him in hands that seemed too rough to be touching such soft skin. Kaladin trembled, then pulled the child tight against him. Memories of this place had not broken him, and seeing his parents had not overwhelmed him, but this…

He could not stop the tears. He felt like a fool. It wasn’t as if this changed anything—Bridge Four were his brothers now, as close to him as any blood relative.

And yet he wept.

“What’s his name?”

“Oroden.”

“Child of peace,” Kaladin whispered. “A good name. A very good name.”

Behind him, an ardent approached with a scroll case. Storms, was that Zeheb? Still alive, it seemed, though she’d always seemed older than the stones themselves. Kaladin handed little Oroden back to his mother, then wiped his eyes and took the scroll case.

People crowded at the edges of the room. He was quite the spectacle: the surgeon’s son turned slave turned Shardbearer. Hearthstone wouldn’t see this much excitement for another hundred years.

At least not if Kaladin had any say about it. He nodded to his father—who had stepped out of the parlor room—then turned to the crowd. “Does anyone here have infused spheres? I will trade you, two chips for one. Bring them forth.”

Syl buzzed around him as a collection was made, and Kaladin’s mother made the trades for him. What he ended up with was only a pouch’s worth, but it seemed vast riches. At the very least, he wasn’t going to need those horses any longer.

He tied the pouch closed, then looked over his shoulder as his father stepped up. Lirin took a small glowing diamond chip from his pocket, then handed it toward Kaladin.

Kaladin accepted it, then glanced at his mother and the little boy in her arms. His brother.

“I want to take you to safety,” he said to Lirin. “I need to leave now, but I’ll be back soon. To take you to—”

“No,” Lirin said.

“Faher, it’s the Desolation,” Kaladin said.

Nearby, people gasped softly, their eyes haunted. Storms; Kaladin should have done this in private. He leaned in toward Lirin. “I know of a place that is safe. For you, Mother. For little Oroden. Please don’t be stubborn, for once in your life.”

“You can take them, if they’ll go,” Lirin said. “But I’m staying here. Particularly if… what you just said is true. These people will need me.”

“We’ll see. I’ll return as soon as I can.” Kaladin set his jaw, then walked to the front door of the manor. He pulled it open, letting in the sounds of rain, the scents of a drowned land.

He paused, looked back at the room full of dirtied townspeople, homeless and frightened. They’d overheard him, but they’d known already. He’d heard them whispering. Voidbringers. The Desolation.

He couldn’t leave them like this.

“You heard correctly,” Kaladin said loudly to the hundred or so people gathered in the manor’s large entry hall—including Roshone and Laral, who stood on the steps up to the second floor. “The Voidbringers have returned.”

Murmurs. Fright.

Kaladin sucked in some of the Stormlight from his pouch. Pure, luminescent smoke began to rise from his skin, distinctly visible in the dim room. He Lashed himself upward so he rose into the air, then added a Lashing downward, leaving him to hover about two feet above the floor, glowing. Syl formed from mist as a Shardspear in his hand.

“Highprince Dalinar Kholin,” Kaladin said, Stormlight puffing before his lips, “has refounded the Knights Radiant. And this time, we will not fail you.”

The expressions in the room ranged from adoring to terrified. Kaladin found his father’s face. Lirin’s jaw had dropped. Hesina clutched her infant child in her arms, and her expression was one of pure delight, an awespren bursting around her head in a blue ring.

You I will protect, little one, Kaladin thought at the child. I will protect them all.

He nodded to his parents, then turned and Lashed himself outward, streaking away into the rain-soaked night. He’d stop at Stringken, about half a day’s walk—or a short flight—to the south and see if he could trade spheres there.

Then he’d hunt some Voidbringers.

Chapter 8

A Powerful Lie

That moment notwithstanding, I can honestly say this book has been brewing in me since my youth.

—From Oathbringer, preface

Shallan drew.

She scraped her drawing pad with agitated, bold streaks. She twisted the charcoal stick in her fingers every few lines, seeking the sharpest points to make the lines a deep black.

“Mmm…” Pattern said from near her calves, where he adorned her skirt like embroidery. “Shallan?”

She kept drawing, filling the page with black strokes.

“Shallan?” Pattern asked. “I understand why you hate me, Shallan. I did not mean to help you kill your mother, but it is what I did. It is what I did.…”

Shallan set her jaw and kept sketching. She sat outside at Urithiru, her back against a cold chunk of stone, her toes frigid, coldspren growing up like spikes around her. Her frazzled hair whipped past her face in a gust of air, and she had to pin the paper of her pad down with her thumbs, one trapped in her left sleeve.

“Shallan…” Pattern said.

“It’s all right,” Shallan said in a hushed voice as the wind died down. “Just… just let me draw.”

“Mmm…” Pattern said. “A powerful lie…”

A simple landscape; she should be able to draw a simple, calming landscape. She sat on the edge of one of the ten Oathgate platforms, which rose ten feet higher than the main plateau. Earlier in the day, she’d activated this Oathgate, bringing forth a few hundred more of the thousands who were waiting at Narak. That would be it for a while: each use of the device used an incredible amount of Stormlight. Even with the gemstones that the newcomers had brought, there wasn’t much to go around.

Plus, there wasn’t much of her to go around. Only an active, full Knight Radiant could work the control buildings at the center of each platform, initiating the swap. For now, that meant only Shallan.

It meant she had to summon her Blade each time. The Blade she’d used to kill her mother. A truth she’d spoken as an Ideal of her order of Radiants.

A truth that she could no longer, therefore, stuff into the back of her mind and forget.

Just draw.

The city dominated her view. It stretched impossibly high, and she struggled to contain the enormous tower on the page. Jasnah had searched this place out in the hope of finding books and records here of ancient date; so far, they hadn’t found anything like that. Instead, Shallan struggled to understand the tower.

If she locked it down into a sketch, would she finally be able to grasp its incredible size? She couldn’t get an angle from which to view the entire tower, so she kept fixating on the little things. The balconies, the shapes of the fields, the cavernous openings—maws to engulf, consume, overwhelm.

She ended up with a sketch not of the tower itself, but instead a criss-crossing of lines on a field of softer charcoal. She stared at the sketch, a windspren passing and troubling the pages. She sighed, dropping her charcoal into her satchel and getting out a damp rag to wipe her freehand fingers.

Down on the plateau, soldiers ran drills. The thought of them all living in that place disturbed Shallan. Which was stupid. It was just a building.

But it was one she couldn’t sketch.

“Shallan…” Pattern said.

“We’ll work it out,” she said, eyes forward. “It’s not your fault my parents are dead. You didn’t cause it.”

“You can hate me,” Pattern said. “I understand.”

Shallan closed her eyes. She didn’t want him to understand. She wanted him to convince her she was wrong. She needed to be wrong.

“I don’t hate you, Pattern,” Shallan said. “I hate the sword.”

“But—”

“The sword isn’t you. The sword is me, my father, the life we led, and the way it got twisted all about.”

“I…” Pattern hummed softly. “I don’t understand.”

I’d be shocked if you did, Shallan thought. Because I sure don’t. Fortunately, she had a distraction coming her way in the form of a scout climbing up the ramp to the platform where Shallan perched. The darkeyed woman wore white and blue, with trousers beneath a runner’s skirt, and had long, dark Alethi hair.

“Um, Brightness Radiant?” the scout asked after bowing. “The highprince has requested your presence.”

“Bother,” Shallan said, while inwardly relieved to have something to do. She handed the scout her sketchbook to hold while she packed up her satchel.

Dun spheres, she noted.

While three of the highprinces had joined Dalinar on his expedition to the center of the Shattered Plains, the greater number had remained behind. When the unexpected highstorm had come, Hatham had received word via spanreed from scouts out along the plains.

His warcamp had been able to get out most of their spheres for recharging before the storm hit, giving him a huge amount of Stormlight compared to the rest of them. He was becoming a wealthy man as Dalinar traded for infused spheres to work the Oathgate and bring in supplies.

Compared to that, providing spheres to her to practice her Lightweaving wasn’t a terrible expense—but she still felt guilty to see that she’d drained two of them by consuming Stormlight to help her with the chill air. She’d have to be careful about that.

She got everything packed, then reached back for the sketchbook and found the scout woman flipping through the pages with wide eyes. “Brightness…” she said. “These are amazing.”

Several were sketches as if looking up from the base of the tower, catching a vague sense of Urithiru’s stateliness, but more giving a sense of vertigo. With dissatisfaction, Shallan realized she’d enhanced the surreal nature of the sketches with impossible vanishing points and perspective.

“I’ve been trying to draw the tower,” Shallan said, “but I can’t get it from the right angle.” Maybe when Brightlord Brooding-Eyes returned, he could fly her to another peak along the mountain chain.

“I’ve never seen anything like these,” the scout said, flipping pages. “What do you call it?”

“Surrealism,” Shallan said, taking the large sketchbook back and tucking it under her arm. “It was an old artistic movement. I guess I defaulted to it when I couldn’t get the picture to look how I wanted. Hardly anyone bothers with it anymore except students.”

“It made my eyes make my brain think it forgot to wake up.”

Shallan gestured, and the scout led the way back down and across the plateau. Here, Shallan noticed that more than a few soldiers on the field had stopped their drills and were watching her. Bother. She would never again return to being just Shallan, the insignificant girl from a backwater town. She was now “Brightness Radiant,” ostensibly from the Order of Elsecallers. She’d persuaded Dalinar to pretend—in public, at least—that Shallan was from an order that couldn’t make illusions. She needed to keep that secret from spreading, or her effectiveness would be weakened.

The soldiers stared at her as if they expected her to grow Shardplate, shoot gouts of flame from her eyes, and fly off to tear down a mountain or two. Probably should try to act more composed, Shallan thought to herself. More… knightly?

She glanced at a soldier who wore the gold and red of Hatham’s army. He immediately looked down and rubbed at the glyphward prayer tied around his upper right arm. Dalinar was determined to recover the reputation of the Radiants, but storms, you couldn’t change an entire nation’s perspective in a matter of a few months. The ancient Knights Radiant had betrayed humankind; while many Alethi seemed willing to give the orders a fresh start, others weren’t so charitable.

Still, she tried to keep her head high, her back straight, and to walk more like her tutors had always instructed. Power was an illusion of perception, as Jasnah had said. The first step to being in control was to see yourself as capable of being in control.

The scout led her into the tower and up a flight of stairs, toward Dalinar’s secure section. “Brightness?” the woman asked as they walked. “Can I ask you a question?”

“As that was a question, apparently you can.”

“Oh, um. Huh.”

“It’s fine. What did you want to know?”

“You’re… a Radiant.”

“That one was actually a statement, and that’s making me doubt my previous assertion.”

“I’m sorry. I just… I’m curious, Brightness. How does it work? Being a Radiant? You have a Shardblade?”

So that was where this was going. “I assure you,” Shallan said, “it is quite possible to remain properly feminine while fulfilling my duties as a knight.”

“Oh,” the scout said. Oddly, she seemed disappointed by that response.

“Of course, Brightness.”

Urithiru seemed to have been crafted straight from the rock of a mountain, like a sculpture. Indeed, there weren’t seams at the corners of rooms, nor were there distinct bricks or blocks in the walls. Much of the stone exposed thin lines of strata. Beautiful lines of varied hue, like layers of cloth stacked in a merchant’s shop.

The corridors often twisted about in strange curves, rarely running straight toward an intersection. Dalinar suggested that perhaps this was to fool invaders, like a castle fortification. The sweeping turns and lack of seams made the corridors feel like tunnels.

Shallan didn’t need a guide—the strata that cut through the walls had distinctive patterns. Others seemed to have trouble telling those apart, and talked of painting the floors with guidelines. Couldn’t they distinguish the pattern here of wide reddish strata alternating with smaller yellow ones? Just go in the direction where the lines were sloping slightly upward, and you’d head toward Dalinar’s quarters.

They soon arrived, and the scout took up duty at the door in case her services were needed again. Shallan entered a room that only a day before had been empty, but was now arrayed with furniture, creating a large meeting place right outside Dalinar and Navani’s private rooms.

Adolin, Renarin, and Navani sat before Dalinar, who stood with hands on hips, contemplating a map of Roshar on the wall. Though the place was stuffed with rugs and plush furniture, the finery fit this bleak chamber like a lady’s havah fit a pig.

“I don’t know how to approach the Azish, Father,” Renarin was saying as she entered. “Their new emperor makes them unpredictable.”

“They’re Azish,” Adolin said, giving Shallan a wave with his unwounded hand. “How can they not be predictable? Doesn’t their government mandate how to peel your fruit?”

“That’s a stereotype,” Renarin said. He wore his Bridge Four uniform, but had a blanket over his shoulders and was holding a cup of steaming tea, though the room wasn’t particularly cold. “Yes, they have a large bureaucracy. A change in government is still going to cause upheaval. In fact, it might be easier for this new Azish emperor to change policy, since policy is well defined enough to change.”

“I wouldn’t worry about the Azish,” Navani said, tapping her notepad with a pen, then writing something in it. “They’ll listen to reason; they always do. What about Tukar and Emul? I wouldn’t be surprised if that war of theirs is enough to distract them even from the return of the Desolations.”

Dalinar grunted, rubbing his chin with one hand. “There’s that warlord in Tukar. What’s his name?”

“Tezim,” Navani said. “Claims he’s an aspect of the Almighty.”

Shallan sniffed as she slipped into the seat beside Adolin, setting her satchel and drawing pad on the floor. “Aspect of the Almighty? At least he’s humble.”

Dalinar turned toward her, then clasped his hands behind his back. Storms. He always seemed so… large. Bigger than any room he was in, brow perpetually furrowed by the deepest of thoughts. Dalinar Kholin could make choosing what to have for breakfast look like the most important decision in all of Roshar.

“Brightness Shallan,” he said. “Tell me, how would you deal with the Makabaki kingdoms? Now that the storm has come as we warned, we have an opportunity to approach them from a position of strength. Azir is the most important, but just faced a succession crisis. Emul and Tukar are, of course, at war, as Navani noted. We could certainly use Tashikk’s information networks, but they’re so isolationist. That leaves Yezier and Liafor. Perhaps the weight of their involvement would persuade their neighbors?”

He turned toward her expectantly.

“Yes, yes…” Shallan said, thoughtful. “I have heard of several of those places.”

Dalinar drew his lips to a line, and Pattern hummed in concern on her skirts. Dalinar did not seem the type of man you joked with.

“I’m sorry, Brightlord,” Shallan continued, leaning back in her chair. “But I’m confused as to why you want my input. I know of those kingdoms, of course—but my knowledge is an academic thing. I could probably name their primary export for you, but as to foreign policy… well, I’d never even spoken to someone from Alethkar before leaving my homeland. And we’re neighbors!”

“I see,” Dalinar said softly. “Does your spren offer some counsel? Could you bring him out to speak to us?”

“Pattern? He’s not particularly knowledgeable about our kind, which is sort of why he’s here in the first place.” She shifted in her seat. “And to be frank, Brightlord, I think he’s scared of you.”

“Well, he’s obviously not a fool,” Adolin noted.

Dalinar shot his son a glance.

“Don’t be like that, Father,” Adolin said. “If anyone would be able to go about intimidating forces of nature, it would be you.”

Dalinar sighed, turning and resting his hand on the map. Curiously, it was Renarin who stood up, setting aside his blanket and cup, then walked over to put his hand on his father’s shoulder. The youth looked even more spindly than normal when standing beside Dalinar, and though his hair wasn’t as blond as Adolin’s, it was still patched with yellow. He seemed such a strange contrast to Dalinar, cut from almost entirely different cloth.

“It’s just so big, son,” Dalinar said, looking at the map. “How can I unite all of Roshar when I’ve never even visited many of these kingdoms? Young Shallan spoke wisdom, though she might not have recognized it. We don’t know these people. Now I’m expected to be responsible for them? I wish I could see it all.…”

Shallan shifted in her seat, feeling as if she’d been forgotten. Perhaps he’d sent for her because he’d wanted to seek the aid of his Radiants, but the Kholin dynamic had always been a family one. In that, she was an intruder.

Dalinar turned and walked to fetch a cup of wine from a warmed pitcher near the door. As he passed Shallan, she felt something unusual. A leaping within her, as if part of her were being pulled by him.

He walked past again, holding a cup, and Shallan slipped from her seat, following him toward the map on the wall. She breathed in as she walked, drawing Stormlight from her satchel in a shimmering stream. It infused her, glowing from her skin.

She rested her freehand against the map. Stormlight poured off her, illuminating the map in a swirling tempest of Light. She didn’t exactly understand what she was doing, but she rarely did. Art wasn’t about understanding, but about knowing.

The Stormlight streamed off the map, passing between her and Dalinar in a rush, causing Navani to scramble off her seat and back away. The Light swirled in the chamber and became another, larger map—floating at about table height—in the center of the room. Mountains grew up like furrows in a piece of cloth pressed together. Vast plains shone green from vines and fields of grass. Barren stormward hillsides grew splendid shadows of life on the leeward sides. Stormfather… as she watched, the topography of the landscape became real.

Shallan’s breath caught. Had she done that? How? Her illusions usually required a previous drawing to imitate.

The map stretched to the sides of the room, shimmering at the edges. Adolin stood up from his seat, crashing through the middle of the illusion somewhere near Kharbranth. Wisps of Stormlight broke around him, but when he moved, the image swirled and neatly re-formed behind him.

“How…” Dalinar leaned down near their section, which detailed the Reshi Isles. “The detail is amazing. I can almost see the cities. What did you do?”

“I don’t know if I did anything,” Shallan said, stepping into the illusion, feeling the Stormlight swirl around her. Despite the detail, the perspective was still from very far away, and the mountains weren’t even as tall as one of her fingernails. “I couldn’t have created this, Brightlord. I don’t have the knowledge.”

“Well I didn’t do it,” Renarin said. “The Stormlight quite certainly came from you, Brightness.”

“Yes, well, your father was tugging on me at the time.”

“Tugging?” Adolin asked.

“The Stormfather,” Dalinar said. “This is his influence—this is what he sees each time a storm blows across Roshar. It wasn’t me or you, but us. Somehow.”

“Well,” Shallan noted, “you were complaining about not being able to take it all in.”

“How much Stormlight did this take?” Navani asked, rounding the outside of the new, vibrant map.

Shallan checked her satchel. “Um… all of it.”

“We’ll get you more,” Navani said with a sigh.

“I’m sorry for—”

“No,” Dalinar said. “Having my Radiants practice with their powers is among the most valuable resources I could purchase right now. Even if Hatham makes us pay through the nose for spheres.”

Dalinar strode through the image, disrupting it in a swirl around him. He stopped near the center, beside the location of Urithiru. He looked from one side of the room to the other in a long, slow survey.

“Ten cities,” he whispered. “Ten kingdoms. Ten Oathgates connecting them from long ago. This is how we fight it. This is how we begin. We don’t start by saving the world—we start with this simple step. We protect the cities with Oathgates.

“The Voidbringers are everywhere, but we can be more mobile. We can shore up capitals, deliver food or Soulcasters quickly between kingdoms. We can make those ten cities bastions of light and strength. But we must be quick. He’s coming. The man with nine shadows…”

“What’s this?” Shallan said, perking up.

“The enemy’s champion,” Dalinar said, eyes narrowing. “In the visions, Honor told me our best chance of survival involved forcing Odium to accept a contest of champions. I’ve seen the enemy’s champion—a creature in black armor, with red eyes. A parshman perhaps. It had nine shadows.”

Nearby, Renarin had turned toward his father, eyes wide, jaw dropping. Nobody else seemed to notice.

“Azimir, capital of Azir,” Dalinar said, stepping from Urithiru to the center of Azir to the west, “is home to an Oathgate. We need to open it and gain the trust of the Azish. They will be important to our cause.”

He stepped farther to the west. “There’s an Oathgate hidden in Shinovar. Another in the capital of Babatharnam, and a fourth in far-off Rall Elorim, City of Shadows.”

“Another in Rira,” Navani said, joining him. “Jasnah thought it was in Kurth. A sixth was lost in Aimia, the island that was destroyed.”

Dalinar grunted, then turned toward the map’s eastern section. “Jah Keved makes seven,” he said, stepping into Shallan’s homeland. “Thaylen City is eight. Then the Shattered Plains, which we hold.”

“And the last one is in Kholinar,” Adolin said softly. “Our home.”

Shallan approached and touched him on the arm. Spanreed communication into the city had stopped working. Nobody knew the status of Kholinar; their best clue had come via Kaladin’s spanreed message.

“We start small,” Dalinar said, “with a few of the most important to holding the world. Azir. Jah Keved. Thaylenah. We’ll contact other nations, but our focus is on these three powerhouses. Azir for its organization and political clout. Thaylenah for its shipping and naval prowess. Jah Keved for its manpower. Brightness Davar, any insight you could offer into your homeland—and its status following the civil war—would be appreciated.”

“And Kholinar?” Adolin asked.

A knock at the door interrupted Dalinar’s response. He called admittance, and the scout from before peeked in. “Brightlord,” she said, looking concerned. “There’s something you need to see.”

“What is it, Lyn?”

“Brightlord, sir. There’s… there’s been another murder.”

Chapter 9

The Threads of a Screw

The sum of my experiences has pointed at this moment. This decision.

—From Oathbringer, preface

One benefit of having become “Brightness Radiant” was that for once, Shallan was expected to be a part of important events.

Nobody questioned her presence during the rush through the corridors, lit by oil lanterns carried by guards. Nobody thought she was out of place; nobody even considered the propriety of leading a young woman to the scene of a brutal murder. What a welcome change.

From what she overheard the scout telling Dalinar, the corpse had been a lighteyed officer named Vedekar Perel. He was from Sebarial’s army, but Shallan didn’t know him. The body had been discovered by a scouting party in a remote part of the tower’s second level.

As they drew nearer, Dalinar and his guards jogged the rest of the distance, outpacing Shallan. Storming Alethi long legs. She tried to suck in some Stormlight—but she’d used it all on that blasted map, which had disintegrated into a puff of Light as they’d left.

That left her exhausted and annoyed. Ahead of her, Adolin stopped and looked back. He danced a moment, as if impatient, then hurried to her instead of running ahead.

“Thanks,” Shallan said as he fell into step beside her.

“It’s not like he can get more dead, eh?” he said, then chuckled awkwardly. Something about this had him seriously disturbed.

He reached for her hand with his hurt one, which was still splinted, then winced. She took his arm instead, and he held up his oil lantern as they hurried on. The strata here spiraled, twisting around the floor, ceiling, and walls like the threads of a screw. It was striking enough that Shallan took a Memory of it for later sketching.

Shallan and Adolin finally caught up to the others, passing a group of guards maintaining a perimeter. Though Bridge Four had discovered the body, they’d sent for Kholin reinforcements to secure the area.

They protected a medium-sized chamber now lit by a multitude of oil lamps. Shallan paused in the doorway right before a ledge that surrounded a wide square depression, perhaps four feet deep, cut into the stone floor of the room. The wall strata here continued their curving, twisting medley of oranges, reds, and browns—ballooning out across the sides of this chamber in wide bands before coiling back into narrow stripes to continue down the hall that led out the other side.

The dead man lay at the bottom of the cavity. Shallan steeled herself, but even so found the sight nauseating. He lay on his back, and had been stabbed right through the eye. His face was a bloody mess, his clothing disheveled from what looked to have been an extended fight.

Dalinar and Navani stood on the ledge above the pit. His face was stiff, a stone. She stood with her safehand raised to her lips.

“We found him just like this, Brightlord,” said Peet the bridgeman. “We sent for you immediately. Storm me if it doesn’t look exactly the same as what happened to Highprince Sadeas.”

“He’s even lying in the same position,” Navani said, grabbing her skirts and descending a set of steps into the lower area. It made up almost the entire room. In fact…

Shallan looked toward the upper reaches of the chamber, where several stone sculptures—like the heads of horses—extended from the walls with their mouths open. Spouts, she thought. This was a bathing chamber.

Navani knelt beside the body, away from the blood running toward a drain on the far side of the basin. “Remarkable… the positioning, the puncturing of the eye… It’s exactly like what happened to Sadeas. This has to be the same killer.”

Nobody tried to shelter Navani from the sight—as if it were completely proper for the king’s mother to be poking at a corpse. Who knew? Maybe in Alethkar, ladies were expected to do this sort of thing. It was still odd to Shallan how temerarious the Alethi were about towing their women into battle to act as scribes, runners, and scouts.

She looked to Adolin to get his read on the situation, and found him staring, aghast, mouth open and eyes wide. “Adolin?” Shallan asked. “Did you know him?”

He didn’t seem to hear her. “This is impossible,” he muttered. “Impossible.”

“Adolin?”

“I… No, I didn’t know him, Shallan. But I’d assumed… I mean, I figured the death of Sadeas was an isolated crime. You know how he was. Probably got himself into trouble. Any number of people could have wanted him dead, right?”

“Looks like it was something more than that,” Shallan said, folding her arms as Dalinar walked down the steps to join Navani, trailed by Peet, Lopen, and—remarkably—Rlain of Bridge Four. That one drew attention from the other soldiers, several of whom positioned themselves subtly to protect Dalinar from the Parshendi. They considered him a danger, regardless of which uniform he wore.

“Colot?” Dalinar said, looking toward the lighteyed captain who led the soldiers here. “You’re an archer, aren’t you? Fifth Battalion?”

“Yes, sir!”

“We have you scouting the tower with Bridge Four?” Dalinar asked.

“The Windrunners needed extra feet, sir, and access to more scouts and scribes for maps. My archers are mobile. Figured it was better than doing parade drills in the cold, so I volunteered my company.”

Dalinar grunted. “Fifth Battalion… who was your policing force?”

“Eighth Company,” Colot said. “Captain Tallan. Good friend of mine. He… didn’t make it, sir.”

“I’m sorry, Captain,” Dalinar said. “Would you and your men withdraw for a moment so I can consult with my son? Maintain that perimeter until I tell you otherwise, but do inform King Elhokar of this and send a messenger to Sebarial. I’ll visit and tell him about this in person, but he’d best get a warning.”

“Yes, sir,” the lanky archer said, calling orders. The soldiers left, including the bridgemen. As they moved, Shallan felt something prickle at the back of her neck. She shivered, and couldn’t help glancing over her shoulder, hating how this unfathomable building made her feel.

Renarin was standing right behind her. She jumped, letting out a pathetic squeak. Then she blushed furiously; she’d forgotten he was even with them. A few shamespren faded into view around her, floating white and red flower petals. She’d rarely attracted those, which was a wonder. She’d have thought they would take up permanent residence nearby.

“Sorry,” Renarin mumbled. “Didn’t mean to sneak up on you.”

Adolin walked down into the room’s basin, still looking distracted. Was he that upset by finding a murderer among them? People tried to kill him practically every day. Shallan grabbed the skirt of her havah and followed him down, staying clear of the blood.

“This is troubling,” Dalinar said. “We face a terrible threat that would wipe our kind from Roshar like leaves before the stormwall. I don’t have time to worry about a murderer slinking through these tunnels.” He looked up at Adolin. “Most of the men I’d have assigned to an investigation like this are dead. Niter, Malan… the King’s Guard is no better, and the bridgemen—for all their fine qualities—have no experience with this sort of thing. I’ll need to leave it to you, son.”

“Me?” Adolin said.

“You did well investigating the incident with the king’s saddle, even if that turned out to be something of a wind chase. Aladar is Highprince of Information. Go to him, explain what happened, and set one of his policing teams to investigate. Then work with them as my liaison.”

“You want me,” Adolin said, “to investigate who killed Sadeas.”

Dalinar nodded, squatting down beside the corpse, though Shallan had no idea what he expected to see. The fellow was very dead. “Perhaps if I put my son on the job, it will convince people I’m serious about finding the killer. Perhaps not—they might just think I’ve put someone in charge who can keep the secret. Storms, I miss Jasnah. She would have known how to spin this, to keep opinion from turning against us in court.

“Either way, son, stay on this. Make sure the remaining highprinces at least know that we consider these murders a priority, and that we are dedicated to finding the one who committed them.”

Adolin swallowed. “I understand.”

Shallan narrowed her eyes. What had gotten into him? She glanced toward Renarin, who still stood up above, on the walkway around the empty pool. He watched Adolin with unblinking sapphire eyes. He was always a little strange, but he seemed to know something she didn’t.

On her skirt, Pattern hummed softly.

Dalinar and Navani eventually left to speak with Sebarial. Once they were gone, Shallan seized Adolin by the arm. “What’s wrong?” she hissed. “You knew that dead man, didn’t you? Do you know who killed him?”

He looked her in the eyes. “I have no idea who did this, Shallan. But I am going to find out.”

She held his light blue eyes, weighing his gaze. Storms, what was she thinking? Adolin was a wonderful man, but he was about as deceitful as a newborn.

He stalked off, and Shallan hurried after him. Renarin remained in the room, looking down the hall after them until Shallan got far enough away that—over her shoulder—she could no longer see him.

Oathbringer: The Stormlight Archive Book 3 copyright © 2017 Dragonsteel Entertainment, LLC