In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

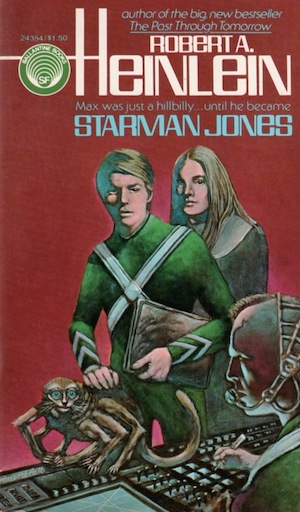

As Robert Heinlein’s juvenile series progressed, the tales took place further and further from Earth. And with Starman Jones, the series left the Solar System entirely, following the adventures of young Max Jones, a gifted young man who wants nothing more than to emulate his space-faring uncle and venture out into the galaxy. Along the way, he makes friends, breaks rules, learns new skills, and has adventures enough to last a lifetime.

Heinlein always did something different with each juvenile. In Starman Jones, more clearly than any other book in the series, the tale explores the difference between laws and regulations on one hand and morality on the other, and examines how those who break the law can also be in the right. My first exposure to Starman Jones was a library copy, which I believe I read in my twenties. By that age, I was used to stories where the lines between right and wrong were blurred. I wonder what my reaction would have been if I had read it in my early teens, like some of the other Heinlein juveniles.

For this review, I used a paperback copy borrowed from my son, and then found the book included in a Science Fiction Book Club omnibus edition entitled To the Stars.

About the Author

Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988) was one of America’s most widely revered science fiction authors, frequently referred to as the Dean of Science Fiction. I have often reviewed his work in this column, including Starship Troopers, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, “Destination Moon” (contained in the collection Three Times Infinity), and The Pursuit of the Pankera/The Number of the Beast, and Glory Road. From 1947 to 1958, he also wrote a series of a dozen juvenile novels for Charles Scribner’s Sons, a firm whose children’s divisions was interested in publishing science fiction novels targeted at young boys. These novels include a wide variety of tales, and contain some of Heinlein’s best work (Note: I’ve linked to the reviews of books I’ve already discussed in this column): Rocket Ship Galileo, Space Cadet, Red Planet, Farmer in the Sky, Between Planets, The Rolling Stones, Starman Jones, The Star Beast, Tunnel in the Sky, Time for the Stars, Citizen of the Galaxy, and Have Spacesuit Will Travel. This is not the first time Starman Jones has been discussed on Tor.com, as Jo Walton reviewed it over a decade ago.

Predictions Gone Right and Predictions Gone Wrong

Looking at older science fiction stories, especially ones like Starman Jones written over seven decades ago, it is always interesting to see what predictions the authors got right, and which fell short. The prediction or assumption that ship’s crews would always be exclusively male, for example, turned out to be wrong even before the end of the 20th century.

In Starman Jones, young Max has a tough life on the family farm in the Ozarks. There is a maglev train that passes nearby, but it is for the more fortunate, not folks like Max. When Max leaves home, he does so on foot, planning to sleep anywhere he can. Like all who lived through the Great Depression, Heinlein had seen a lot of poverty, and viewed economic inequality as something that would continue into the future. That prediction has held up well over the subsequent decades, and looks like it will continue long into the future. As far back as the New Testament, written nearly 20 centuries ago, Jesus tells his followers that the poor will be with us always, and it sadly appears that betting against that statement will always be a losing proposition.

One place where Heinlein saw the future a little less clearly is in the field of navigation, or “astrogation,” as he calls it. Those scenes were very evocative to me, reminding me of my own days in the 1970s as a deck watch officer on a Coast Guard cutter (and for a short time at the end of my tour, as the navigator myself). The Coast Guard had taken Loran A radionavigation stations offline, but was having problems getting newer Loran C units to work on our class of vessels, so when we were out of radar range of land, we did things the old-fashioned way. The astrogation tables that Max has memorized bear no small resemblance to Publication 229, the Sight Reduction Tables for Marine Navigation, which I used with a chronometer, sextant, charts, and other resources to plot my vessel’s position. But the days of old-fashioned navigation were ending. A new ensign reported to the cutter, having been issued a programmable calculator that seemed to be able to spit out pretty much all the numbers from the tables in Pub 229. And Loran C was soon supplanted by yet another system, and mariners had satellite-based GPS to draw upon. The last time I was on the bridge of a cutter, their position was fixed by computer and displayed on a TV screen without need for any human navigator at all, making me feel like an expert in something as archaic as producing buggy whips. Heinlein predicted travel to other stars, but didn’t anticipate the impact that advanced computing devices could have on guiding that travel.

Another computer innovation Heinlein didn’t see coming was the centralized database. The fake credentials that Max and Sam used to gain a berth on a star liner would not have survived modern scrutiny, and cross-checking with electronic records. For better or worse, there is much less opportunity for someone in modern society to put their old life behind them and start anew.

And those fake credentials bring up another topic, more based on sociology than technology. When I went to sea, sailors could be a rough lot. They worked hard, but they also got into trouble, and competence was valued over conformance to regulations. One of the best petty officers on my ship had made second-class petty officer three or four times, losing that rank again and again because of disciplinary infractions, but regaining it because of his skills and abilities. In subsequent decades, with the best of intentions, there arose an emphasis on “zero tolerance” for disciplinary actions, and for officers in particular, any hint of negativity in a fitness report could end a career. The days of the capable rogue were ending, and conformity became the watchword. I hope that is not a lasting trend, and that the pendulum will eventually swing back the other way. I would rather serve with someone competent, even if they are rough around the edges, than someone who presents themselves well and looks good on paper. The character Sam in Starman Jones might not be someone I would trust with my wallet, but I would trust him with my life.

Starman Jones

As mentioned above, we’re introduced to Max Jones while he’s working on the family farm. About the only possessions Max has are a claim to the farm (controlled after his father’s death by his unreliable stepmother), and a set of interstellar navigation tables left to him by his late uncle. When a new stepfather enters the picture and it looks like the land will be sold off, Max hits the road on foot to the nearest spaceport, hoping his uncle left word that he should be admitted to the hereditary astrogators guild. Max is blessed with an eidetic memory, which we see him use to calculate the time by the position of the stars, and also to recall train schedules, so he can cut through the maglev train tunnel to save time. His calculations are a bit off, however, and he is almost squished into a pulp by the shockwave of a passing train as he leaves the tunnel. Max has also memorized those books of astrogation tables, a skill that will be vital later in the story.

Max meets a hobo named Sam, who shares his dinner. Sam coaxes Max’s story out of him, and Max admits that if his uncle, who was childless, registered Max with the astrogator’s guild, he might be able to join. They go to sleep, and Max awakens to find Sam gone, along with the astrogation tables, which are worth money if turned back into the guild. Max continues on and reports to the guild hall, to find that Sam, impersonating him, had attempted to turn in the tables, but was rebuffed. They sadly inform Max that his uncle left no instructions for him, but pay him the bounty for returning the tables.

Max then encounters Sam again, and is convinced to spend his bounty on fake identification papers for the stewards guild that will get them a berth on the space liner Asgard, and off into space. Sam tells Max the story of a man he knew, an Imperial Marine named Roberts or Richards, who missed a ship’s movement, did not want to face the consequences, and kept putting off surrendering himself to the authorities. While Sam denies it, Max suspects he was that Marine (the idea that humanity is now organized into an empire is intriguing, but Heinlein doesn’t waste time explaining that further).

Max doesn’t enjoy the work of a steward, but does his best at menial tasks like caring for the pets of the rich passengers. One of these is a spider puppy named Mr. Chips, owned by a young woman named Eldreth. She takes a liking to Max, and soon has wrangled permission from his boss for him to play three-dimensional chess with her. She turns out to be quite a well-connected passenger, is impressed by his knowledge and math skills, and advocates for him with the ship’s officers. The next thing Max knows, he is being allowed to strike for a position as junior chartsman, working alongside the astrogators.

The Chief Astrogator, Doctor Hendrix, is a kindly man, and served with Max’s uncle. But one of the junior astrogators, a sour man named Simes, is not very competent and jealous of anyone who might compete with him. We get a lot of descriptions of astrogation procedures which, despite the outdated technology, feel very true to what happens on the bridge of a ship. Max does well enough that he is designated as a merchant cadet, which allows him to dine with passengers, including his friend Eldreth. Meanwhile, while he proves himself an able leader, Sam can’t avoid the temptation to get involved in some irregular activities, and get busted down to swabbing decks.

Buy the Book

Exordia

Soon the death of Doctor Hendrix upsets the smooth operation of the astrogation department, and in a critical maneuver, the Captain makes an error that sends the Asgard to unknown regions, where it appears likely they will be trapped forever. They find a habitable planet, but order and discipline begin to break down as people realize they might never get home. The Captain has a nervous breakdown, and before long, is dead. And when the planet turns out to be inhabited by mysterious and malevolent aliens, their situation looks even bleaker. Soon, Max and Eldreth are captured by the aliens, and taken to meet their fate—which might even involve ending up in a cookpot. But the little spider puppy Mr. Chips knows where they are, and Sam soon heads out to the rescue. It turns out they have one last hope for leaving the planet…and it requires Max, and his perfect memory, to get back to the ship.

The book has a wonderfully bittersweet ending, a very fitting conclusion to one of Heinlein’s better juveniles. Max, despite his incredible mathematics abilities, feels very real and grounded. And Eldreth, despite being present in the tale as the obligatory love interest, is a strong character in her own right. But it is Sam, equally gifted and flawed, who steals the limelight every time he is mentioned, becoming one of my favorites of all Heinlein’s characters.

Final Thoughts

Starman Jones is an enjoyable volume in Heinlein’s series of juveniles, definitely ranking near the top of the list. There is lots of action and adventure, plenty of jeopardy, engaging characters, and interesting moral dilemmas.

And now it is time for you to talk and me to listen: What did you think of Starman Jones? How do you think it stacks up against Heinlein’s other juveniles? And as a fan of stories involving navigators managing faster-than-light travel, I’d enjoy hearing about other such stories you may have encountered.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.