Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

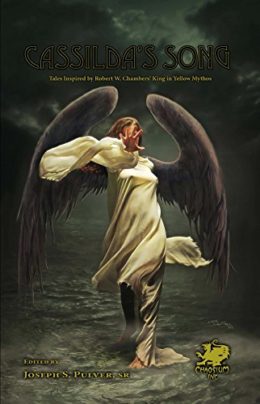

This week, we’re reading Nadia Bulkin’s “Pro Patria,” first published in 2015 in Joseph S. Pulver’s Cassilda’s Song anthology. Spoilers ahead. Trigger warning for suicide.

“Joseph Garanga watched a small brown gecko crawl, belly to the wood, across the open window sill, and wondered why an institution that called itself the National University had installed neither window panes nor air conditioning.”

Summary

Joseph Garanga, political science professor at the National University of Concordia, isn’t entirely displeased when graffiti proclaims that “Garanga’s Law” is “The Restitution of the Damned.” He doesn’t know what that means, but it’s flattering to think he’s been elevated to the level of a Newton or Fermi, even if by a populace incapable of driving through an intersection without inviting head injury. After all, he is one of the few competent social scientists keeping newly independent Concordia from rolling out of the cradle and cracking open its skull. Wasn’t he President Michael Dayamon’s university mentor? Who guided the new President through the nationalization of companies wrested from the ousted Empire? Who’s helping him draft a constitution to replace the interim mishmash cobbled together on the eve of revolution?

Joseph’s irritated when literature professor Robert Fileppo interrupts his conference with graduate student Adela to ask if he’s “seen the yellow sign.” What new nonsense is this? Fileppo’s astonished Joseph hasn’t read the book. It’s all about Joseph’s subject, see. Governance.

The book Fileppo puts on Joseph’s desk is leatherbound, redolent of the dungeon. The King in Yellow. Sounds like a child’s book, and Joseph immediately hates the thing. Adela, however, would like to read it. Fileppo looks over dark-skinned Adela and remarks that the book hasn’t been translated yet. Grimly she says she doesn’t need it translated. She knows their former conquerors’ tongue.

President Dayamon summons Joseph to the National Palace. Joseph’s horrified to see that Michael’s exchanged his plain cotton suit for ex-Regent McMurphy’s brass-dripping white uniform. Shock follows shock. It’s one thing for Fileppo to tout the latest fetish of a culture-starved bourgeoisie, but for Michael to produce a copy of The King in Yellow? For him to call it “the new Machiavelli” and say that “the top minds in the world’s capitals are all studying this text”? Joseph cautions Michael that their old rulers don’t have all the answers.

Michael chuckles. He remembers all that. But the King has made him rethink the draft constitution. The King teaches that as president, he, Michael, embodies the nation. Who threatens him, threatens the state. That means rules like parliamentary approval, direct elections, independent justices, all leave imperialist counter-revolutionaries too much wiggle-room.

But there are no counter-revolutionaries! Besides, the constitution isn’t only about Michael but future presidents….

The blank look on Michael’s face, as if he can’t conceive of anyone else leading Concordia, makes Joseph remember who commands the soldiers’ bullets. He leaves thinking bitterly of the revolution’s end, when he’d dreamt of “rebirth and amnesia, of the red sun taking the spilled blood down into the darkness… It would never happen.”

Good as his threat, Michael cancels constitutional reform. Joseph commutes to work past unfinished high-rises, boy soldiers in misfit helmets, billboards shouting Onward to Victory. What victory? Over all spreads the spray-painted taunt Garanga’s Law: The Restitution of the Damned.

One morning Adela waits outside his office as if she’s been there all night. Pursuing her research on the persistence of colonist messaging, she’s been haunting the library’s projection room. This one film, on transmigration eastward? In the background, in locations thousands of miles apart, there’s a figure in a long yellow robe. He walks through the trees, or floats. When he’s on screen, you have to watch and wait for him to notice you. You never see his face, but Adela knows what it all means. They’re going to come back.

It does no good to reassure Adela that the colonists are fighting their own war far away. Fear’s overwhelmed her, made her feel like a throwaway peasant girl again. In the streets yet another military parade blares an unrecognizable battle hymn. Joseph can’t find that damned yellow king book to burn, and now Adela’s sobbing that Garanga’s Law means the colonists are the damned, and their restitution will be their old empire.

A midnight comes when Joseph’s summoned to the National Palace to watch Michael rummage through dusty rooms at the bidding of a village psychic. Finally she proclaims: “There is a ghost.” Michael knew it! Joseph mourns—before the yellow king, Michael seemed immune to superstition. “You inherited it from them,” the psychic says. “You take the palace, you take the ghost.”

Michael doesn’t want it. It’s foul.

She replies: “But it wants you.”

Asked for a “policy prescription” for exorcising the ghost, Joseph flees. On the way to his office, he passes the library. Something runs across its roof, jumps, dies in front of his car. Adela. He lifts her corpse, to see the missing King in Yellow fall from her jacket. He flips through it, noting her violent marginalia but none of the text, though maybe he should read a few words, join the rest of the madding crowd.

Another evening, an Independence Day party. The palace grounds are packed with the elite of Concordia, and with armed guards. Atop the palace steps, in the white uniform, Michael overlooks the crowd. When Joseph joins him, he says he is about to vanquish that ghost, for the King in Yellow tells us—

Damn that book, Joseph cries, it’s an evil, probably from them! The revolution is over. We won. We’re free. We just have to….

Stop bleeding.

No, Michael says. The revolution is never over. While there’s an Empire, they’re at our door. He raises his arms like an orchestra conductor, announces that it is time to be rid of the ghost of Empire. Vigorous applause from the crowd. But wait! First there are traitors to root out!

The first Michael points out is Fileppo, the literature professor. Does he love his country? Would he do anything for his fatherland? Fileppo’s too stunned to answer and receives Michael’s shouted condemnation of “Counter-revolutionary!” and a pop-pop-popping of bullets. And so on, wherever Michael points, the state’s will is iron, instantly executed. Joseph screams his throat raw for Michael to stop, but Michael only whispers “I can see him! He moves through the crowd!”

Guards drag Joseph away to a cell in the old imperial prison where pro-independence agitators once languished. Through the bars he watches new enemies of the state meet their ends. Sometimes, when it rains, he sees a yellow-robed figure gliding through the trees on the other side of the electrified fence. Joseph doesn’t think it claims Concordia for the Empire, which splinters across the sea. It’s something older, truer, maybe dreamt into being by the Empire.

Something that would have its restitution.

What’s Cyclopean: The interim constitution is a “freakish cassowary.” Personally I would consider a cassowary an excellent symbol for a newborn country: you try making one do anything it doesn’t want to do. I’ll just stand over here.

The Degenerate Dutch: Fileppo, whose family have somehow held onto their tea plantation, dismisses graduate student Adela for her dark skin and rural background, assuming that she can’t read the conqueror’s tongue.

Mythos Making: Along with the book itself, a yellow-robed figure stalks Joseph’s country. “They”—the great, uncaring powers that serve the King—are coming back.

Libronomicon: The King in Yellow is leather-bound (or bound in something like leather), author-less, and smells like a dungeon. Ostensibly it’s a political treatise. Joseph describes its uninformative cover as a “mask.”

Madness Takes Its Toll: President Michael Dayamon, post-King, giggles and blubbers “like an asylum escapee” as he tries to track and destroy the ghost of empire.

Buy the Book

Deep Roots

Ruthanna’s Commentary

What is The King in Yellow? Is it, as sometimes claimed, merely a play—or at least the script for one? The sort of thing that you might see on the Tony Awards? Is it a book, limited edition, to be passed surreptitiously hand to hand or banned in schools or pushed, briefly and violently, to the top of best-seller lists? Perhaps it’s simply an idea that, once encountered, can never be forgotten. It seeps into every thought, influences every decision, colors the world in new patterns. It’s that new word that you’ve just started hearing everywhere, out of context. You haven’t learned yet what it means. All you know is that, once you do learn, you’re going to regret it.

And yet, you are going to learn, aren’t you? After all, everyone else is talking about it. Being the only one who doesn’t know would be worse.

In Chambers’ original four stories, the play inspires art, madness, and dictatorial revolution (unless it doesn’t, unless it’s all an illusion in the mind of the reader). Earlier Cassilda’s Song selections “Black Stars on Canvas” and “Strange is the Night” focus on its decadent artistic side, maddening or glorious but always provoking. Robin Laws’s follow-ups take the revolution from “Repairer of Reputations” as literal truth, and fill in a whole history around it. “Repairer” itself, whether it depicts reality or delusion, is unreservedly and sharply political. It’s this aspect that Nadia Bulkin makes use of in “Pro Patria.”

There’s something Lovecraftian about politics to begin with. For many people they’re a vast force of which we catch only glimpses, something that can destroy lives on a whim or as a side effect. Those who seek to understand those forces delve into thick tomes written in obscure languages, engage in rituals with only a dim understanding of the results. Those rituals invoke powers that we hope will treat our lives as something real and worthy of attention—and sometimes they do.

Delve still deeper into these eldritch mysteries—perhaps strive to become one of those wielding power—and you may glean vast rewards. You may also be eaten, or simply changed beyond recognition. As happens to Michael Dayamon. Bulkin’s answer to the eternal question of what corrupts revolutions might seem comforting at first—a single book, imposed from outside, insinuating itself into a young, scrappy, hungry country trying to come of age. But Bulkin’s King in Yellow is no mere book. It’s the ideology of empire, the seed of it, taken in by the subjects of colonialism as well as the imperialists, growing perniciously even in the minds of those who rebel. Like descent from white apes or the children of Dagon, it’s a taint extraordinarily difficult—perhaps impossible—to outgrow. (And, not incidentally, the taint whose influence most warped Lovecraft himself, for all he looked for his fears everywhere else.)

Black Panther (a wonderful film, and one I’ll bet you were not expecting to see discussed in this column) shows the flip side of this idea. Wakanda, beautiful and honorable and breathtakingly free, has never been touched by empire or colonialism. Is that what’s necessary? Or is there some way, after immersion in that not-quite-original sin, to resist the pernicious political ideas incubated in the King in Yellow treatise?

Joseph, for all his cynicism, manages this resistance. His frustration with his country, his people, is palpable throughout the story—even before the treatise shows up, he’s not exactly a font of optimism. Still, he has the sense to suspect that his people’s own voices—however clumsy and imperfect—are a better route to independence, maybe even wisdom, then the most polished and well-respected tome from a source that’s known to be cursed.

Now there’s a perspective that would do some people at Miskatonic a world of good.

Buy the Book

Fathomless

Anne’s Commentary

Pro patria! For one’s country! The fatherland, oh you patriots! And because this is the way my mind works, I must suppose that pro matria would be for the motherland, oh you matriots! When patria and matria meet (during the migration of tectonic plates, for example), you should get some baby father- and motherlands, say, a chunk torn off a continent or a freshly risen archipelago or aeons-drowned but young at heart R’lyeh. All ripe for political chaos, since that is how the King in Yellow would have it, according to today’s story.

To spark her contribution to the Cassilda’s Song anthology, Nadia Bulkin appears to have turned to Robert W. Chamber’s first KiY story, “The Repairer of Reputations.” Like Chambers, she sets her tale in a skewed version of the world we know, an alternate reality. The crucial difference is that Chamber’s narrator, Hildred Castaigne, is an infamously unreliable narrator and may be delusional about his futuristic New York of military parades and suicide booths; Bulkin’s Joseph Garanga is tragically reliable, an acute and rational observer of Concordia’s struggles, intellectually vain and snobbish for all his contempt of “lesser” snobs like Fileppo but not without strong sensibilities–and a genuine patriotism, the kind that bleeds. Concordia is not a real nation in our atlases. Garanga’s narration grounds it for us as a real nation in Bulkin’s fictive world, and Concordia’s former colonial master as a real Empire.

So, The King in Yellow must be a real book, too. Everyone who’s anyone in Concordia’s upper crust has read it, including President Michael Dayamon, and Dayamon says that the “top minds” worldwide have read it. It’s the new Prince, as in Machiavelli’s celebrated how-to-win-friends-and-dominate-peoples. For Bulkin to give her KiY a political slant again recalls “The Repairer of Reputations”—Hildred Castaigne concluded from his and “repairer” Wilde’s readings of KiY that Hildred should be the heir of the Last King of the Imperial Dynasty of America, itself descended from a kingdom in the far stars of the Hyades, oh, and by the way, Wilde was running a conspiracy to help Hildred conquer the United States.

The wisdom the King has for Dayamon is more general: As president, he embodies the nation. Those who threaten him, threaten the state. Corollary One (as derived by the always clever student Michael): If he embodies the nation, why shouldn’t most (all?) power rest in his hands? Corollary Two: If a threat to him is a threat to all, isn’t paranoia his presidential duty? Corollary Three: Can dutiful paranoia ever rest while the Empire (any enemy) remains in the world—or internally?

I’ve wondered if that insanity-spawning second act of KiY is specific to each reader. For the “top mind” politicians of the world, I doubt it would have to be. Trigger their egos and fears, as Dayamon’s are triggered, and Concordia fails, the Empire splinters, the nations ignite one by one. In Joseph’s microcosm, he watches his great-hearted student Michael slip away, Adela forget her own journey from peasant girl to doctoral candidate, his nation’s “top minds” gather as sheep to random slaughter to celebrate their Independence Day.

He watches, and worse, he watches sane, because he’s never read The King in Yellow. Nevertheless, from his prison cell, he can see the King glide through the jungle trees on the other side of the killing yard. That’s how strong the King has become, older, truer, damned but come into Its restitution, per Garanga’s Law.

Next week, we enter the Halloween season with a simple tale of love and death in Poe’s “Ligeia.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.