I’ve done three or four interviews now in which I’ve been asked about the literary models I used in my new novel Julian Comstock.

The name I generally mention is Oliver Optic—always good for a blank stare.

Now, I put it to you boys, is it natural for lads from fifteen to eighteen to command ships, defeat pirates, outwit smugglers, and so cover themselves with glory, that Admiral Farragut invites them to dinner, saying, “Noble boy, you are an honor to your country!“

That’s Louisa May Alcott in her novel Eight Cousins, describing the sort of books she called “optical delusions.” She was talking about Oliver Optic, who was sufficiently well-known in the day that she didn’t have to belabor the point. Her description of his work is perfectly apt, but the effect it had on me (and perhaps other readers) was the opposite of the one she intended: Cripes, is there such a book? And if so, where can I find it?

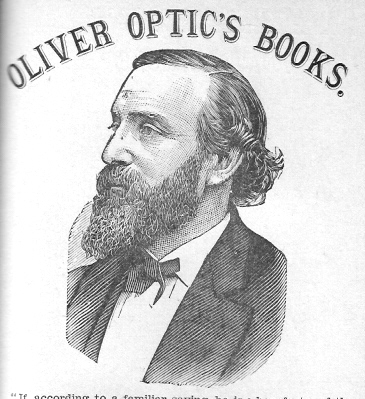

I’ve since tracked down dozens of his novels—they were so popular that there’s no shortage of vintage copies even today—and I was so charmed by the author’s quirky, progressive and always well-intentioned voice that I borrowed liberally from it for Julian Comstock. He was once a household name among literate American families, and he deserves to be better remembered.

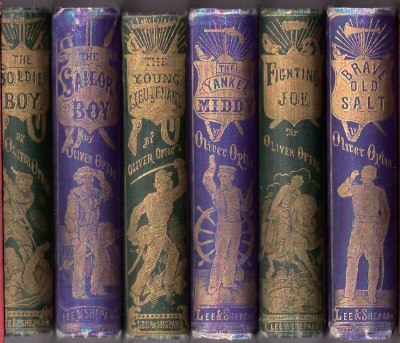

The books Louisa May Alcott was referring to were his Army-Navy series, pictured here. And they’re all you could hope for: breathlessly optimistic stories of train wrecks, steamboat explosions, an escape from Libby Prison, secret codes deciphered, blockade runners foiled, slaveholders defied, betrayals and reverses, etc. etc. You also get Oliver Optic’s weirdly amiable and funny narrative voice—”weird” in the context of the subject matter. The books were written at the end of the Civil War, while the artillery barrels were still cooling and the bodies being shipped home from the battlefields for burial. (There was a boom market at the time for metallized coffins, which made shipping by train more sanitary. Embalming was a new art, often practised by unscrupulous charlatans.)

Oliver Optic himself—his real name was William Taylor Adams—was a born and bred Massachusetts progressive, morally opposed to slavery and friendly to a host of reform movements. His sole work of book-length non-fiction was a boys’ biography of Ulysses S. Grant, which got him invited to Grant’s inauguration following the 1868 election. He served a term in the Massachusetts legislature, and he was an advocate for public education and vocational schools. His fiction can sound condescending to modern ears—some of the dialect passages in his books border on the unforgivable—but his heart is always in the right place: despite our differences we’re all human beings of equal worth.

He had some peculiarities. He traveled widely and often, and his travel stories (Down the Rhine, Up the Baltic, Across India, Asiatic Breezes, etc.) all drew from personal experience. But in the age of the transcontinental railroad, he was mysteriously indifferent to the American west. He seldom mentioned it (except to object to Grant’s maxim that “the only good Indian is a dead Indian”), and even his so-called Great Western series never gets past Detroit, at which point the hero turns around and heads for (inevitably) Massachusetts. The third volume of the Great Western series is subtitled “Yachting Off the Atlantic Coast.”

And I won’t delve into the idea he espoused in his novel The Way of the World, that every public library should have a bowling alley in the basement…

Optic was hurt by Louisa May Alcott’s dig, and some of his later books lean away from the gaudy adventures of the Army-Navy series. Recently a few of his more tepid titles have been brought back into print by Christian presses—perhaps ironically, given that during his lifetime he was denounced from the pulpit as often as he was endorsed from it.

He wasn’t a great writer in the absolute sense, but nothing he wrote was less than endearing. The encomium to L. Frank Baum in the movie The Wizard of Oz applies equally to Oliver Optic: for years his work gave faithful service to the young in heart, and time has been powerless to put its kindly philosophy out of fashion.

His death in 1897 was reported in every major paper including the New York Times. I hope Julian Comstock plays some small part in keeping his memory alive.

Robert Charles Wilson

is the author of the Hugo-winning novel

Spin

. His new novel,

Julian Comstock: A Story of 22nd Century America

, is available now from Tor Books. You can read excerpts from his book

here

.

Could the revelation that Neelix lied and only worked with models be an homage to Hardy Kruger and Giovanni Ribisi’s characters in The Flight of the Phoenix and its remake?

Milo: So I was about to type, “Of course it was inspired by that, didn’t you read the Trivial Matter?” but then I realized that I forgot to put that in the Trivial Matters. Herpity derpity derp. Will go fix that…

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

It’s a decent action thriller, but the mishandling of the space elevator concept annoyed me. I mean, it was nice that they used the concept, possibly the first time it was used in SFTV, but they bungled the specifics. They said the tether is 300 km long, which is a couple of hundred times too short for a viable space elevator around an Earth-sized planet. You need to have the center of mass of the thing at a synchronous orbital altitude, so the period of the orbit is exactly equal to the planet’s rotation period and thus it stays constantly over the same point. And that’s just the center of mass, so you need more tether extending out beyond it an equal length (or else a shorter length with a proportionally massive counterweight). It’s typical of Trek to shrink the size of things that should be ginormous, like the tiny solar sails on Bajoran sailships in DS9: “Explorers” and “Accession.”

I was also frustrated by the reset-to-zero tension between Tuvok and Neelix, and the missed opportunity to follow up on “Tuvix.” That episode ended without making it clear whether they remembered anything from their time as one being, and “Rise” seems to establish that they don’t. But it would’ve been so much more interesting if they had remembered, if this episode had given us the followup that “Tuvix” deserved.

“as his Vulcan physiognomy can handle the thinner air better than the others.”

You mean “physiology.” Physiognomy means facial or outward appearance.

Gyar. Thanks, Christopher, for that catch. I’ve corrected it to the right word. Sigh.

—Keith R.A. DeCandido, grateful for the edit function to catch the dumbshit mistakes he makes while writing after a long day

What is so annoying to me about this (and so many other Neelix moments) is that there is really no reason for him to lie about his experience. They are trapped on this planet, and models or no models, he still has far more experience with this kind of thing than anyone else. All lying did was making it more dangerous, because they likely would have taken further precautions if they knew Neelix’s experiences were mainly theoretical instead of practical.

I think the episode once again makes the mistake of thinking that the audience harbors far more goodwill toward Neelix than we do. Tuvok is meant to come across as mean and dismissive, but he is a trained Starfleet officer with extensive experience, and Neelix is their goofy cook who exaggerates his knowledge and expertise. Even without the “Vulcans don’t have gut instincts” angle, it’s still pretty reasonable that Neelix’s “I have a funny feeling that requires some extremely dangerous and life-threatening actions to confirm” would be ignored. And his desired to be liked by Tuvok is just grating, really. He seems to be well-liked (lord knows why) by the rest of the crew, so it isn’t like he is desperate for friends. He is purposely annoying to Tuvok, and then gets all huffy when a Vulcan doesn’t find it endearing.

I remember liking this one when I first saw it. I thought the space elevator was really cool, it was a fun thing to finally see having come across references to the concept in other fiction. The Tuvok/Neelix interactions never bothered me because I assumed that after “Tuvix” they would have no memory of the event and the relationship here makes that clear. I always liked the way the two characters played off each other and Russ and Phillips do great things with it. I’m glad that bit didn’t change.

Somebody on Facebook asked an interesting question: Is there any reason this episode couldn’t come before “Tuvix”? I can’t think of a reason, other than maybe Janeway’s hairstyle, but then there’s “Parturition” where her hair was short for a week and then magically got long again the next.

@5/wildfyrewarning: “What is so annoying to me about this (and so many other Neelix moments) is that there is really no reason for him to lie about his experience.”

That’s the point, though, that it’s coming from his insecurity, his imagined fears rather than any genuine need. Starfleet characters in Berman-era Trek had to be perfect, but outsiders like Neelix could be screwed up and neurotic and self-defeating.

You know, watching this season again, the whole Neelix and Kes breakup is still really weird. For instance, in this episode, Neelix stops by medical to grab some supplies and briefly interacts with Kes. The interaction is as though the two characters don’t have a history. It’s not like the awkward interaction between exes trying to act normal, but as though they were strangers. I’ve never seen a show just drop a relationship before with very little explanation. It was bizarre when the show first aired and still very much a head-scratcher now.

KRAD wrote:

Or did it? The only way to stay sane with long-running Trek, I’ve found, is to assume each project is purely episodic except when a previous adventure is explicitly referenced; otherwise there’s a “reversion to the mean”, as it were (“reversion to the series bible concept of the characters and milieu”, more pertinently). If two characters have a certain relationship, we can infer that something led to that relationship, but we can’t say what it was — maybe an aired adventure? But conversely, if their relationship goes backwards, maybe an unaired adventure negated it. (While passing through the evidently-not-so-expansive Nekrit Expanse, aliens accidentally wipe their memories and inexpertly restore them. Makes as much sense as anything else this crew endures.)

No, it’s not satisfying if one demands large-scale consistency; but if an episode can entertain me on the small scale, I’ll restrain my complaints in the interest of healthy blood pressure.

I always thought along the same lines as @@@@@6/lesleyk and assumed that Neelix and Tuvok has no memory of Tuvix. I figured that added to the tragedy of the character. Sarek’s memories lived on through Picard/Spock and Data through Lal/B4, but Tuvix just didn’t exist anymore.

I always enjoy space elevators when they pop up, but I guess its name does sound a little silly compared to other names like “Dyson sphere” and “warp drive”. That said, “space elevator” is way better than “orbital tether”! The latter just sounds like more standard technobabble that viewers tend to tune out, rather than an actual scientific concept.