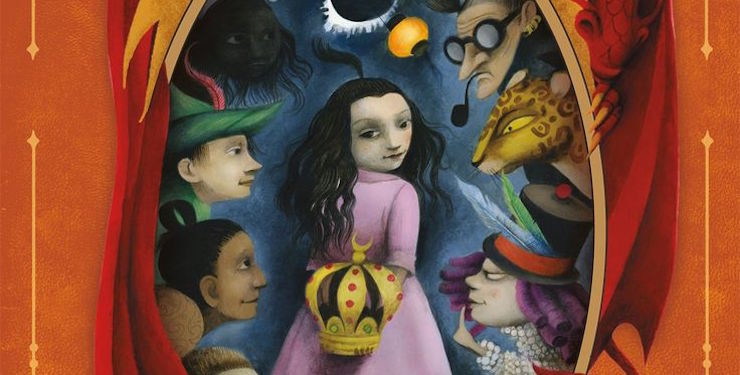

There are a dozen essays a person could write about Catherynne M. Valente’s Fairyland series. One is entirely about the literary allusions and references. Another simply describes all her magical inventions and locations, from the Carriageless Horse to the Narrative Barometer, the Autumn Province to the Lonely Gaol. There’s a really good piece to be written about one of the rules of Fairyland-Below—what goes down must come up—and the way no one stays in the underworld for good, forever, even a shadow.

This is a different essay. This one is about change and subversion, and mostly about how magically a book can rewrite the story of growing up.

Note: this essay discusses plot points from Books 1-4, but contains no spoilers for Book 5.

Many books for young readers, for a very long time, have drawn a very distinct line between being a kid and being an adult, between the land of adults and the land of children—which is filled with magic and possibility, adventures and quests and very clearly marked villains. Parents are generally out of the way in these stories, possibly dead, most definitely not invited along. The adventures are things that could only happen to worthy children, as sweet as Dorothy Gale, as good-hearted as Lucy Pevensie, and usually, when you get a bit older, you’ll have to suffer a loss, whether of the entire magical world (poor Susan) or of the part of it that has your heart (poor Lyra). You have to grow up—a thing which is never presented as very much fun at all.

Fairyland presents a very different model, one where growing up doesn’t have to mean growing out—out of magic, out of believing, and out of wonderful places and new things. As her heroine, September, moves between our world and Fairyland, Valente moves between different kinds of magic: the magic of being young, and the magic of growing up, showing that figuring out who you are and where you belong is not a finite process—and that you can take your magic with you.

I: “No one is ever chosen.”

If you grew up on good-girl stories, like I did, you might be a bit wary of Fairyland at first. If you took those lessons to heart, certain that being good and true and kind was the best road to getting chosen for a magical quest, you might be taken slightly aback when the Green Wind comes to September’s window and says: “You seem an ill-tempered and irascible enough child.” When he asks if she would like to come away with him to Fairyland, she skips right over the part where he says he will deposit her in the sea:

If you grew up on good-girl stories, like I did, you might be a bit wary of Fairyland at first. If you took those lessons to heart, certain that being good and true and kind was the best road to getting chosen for a magical quest, you might be taken slightly aback when the Green Wind comes to September’s window and says: “You seem an ill-tempered and irascible enough child.” When he asks if she would like to come away with him to Fairyland, she skips right over the part where he says he will deposit her in the sea:

“Oh, yes!” breathed September

Ill-tempered and irascible! These aren’t traits that generally earn you a trip to a magical land, unless you count that time Eustace Scrubb got swept along to Narnia with his cousins—and he had to learn his lesson eventually. But what makes September these things? Is she these things, at least the way we think they mean? She’s ill-tempered because she is unsatisfied, because she wants more. At twelve, there’s so much more to want. What the Green Wind calls irascibility is September’s interest in things, her curiosity. She is one of us—us book-readers, us mythology-seekers—and she knows what it means to be carried away to another world.

It means a story, and she wants that story with all her bookish heart. And though, in Valente’s sly narrator’s words, children don’t have hearts, September is 12, and thus only “Somewhat Heartless, and Somewhat Grown.” What drives her first adventure is the conflict between self-interest and a bigger kind of love.

From the start, September’s adventure is full of astonishingly playful, magical language; entering Fairyland is a bureaucratic tangle of Persephone visas and arcane rituals, and when she finally lands on its shores, a series of choices awaits: Which road to take? Who to trust and who to fear? And what to do? Being a child of stories, she takes on a quest. When she meets a pair of witch-sisters who are both married to a wairwulf, she agrees to get one witch’s Spoon back from the Marquess, the current ruler of Fairyland, about whom September has already heard a few things:

The Green Wind frowned into his brambly beard. “All little girls are terrible,” he admitted finally, “but the Marquess, at least, has a very fine hat.”

The Marquess is one of Valente’s greatest creations, and she lives in another: Pandemonium, the capital of Fairyland, which, in a bit of wordplay worthy of The Phantom Tollbooth, moves across the countryside according to the needs of narrative. When September meets The Marquess, she’s manipulative, wheedling, vicious and unpredictable. Both childish and wickedly smart, when she doesn’t get her way, she resorts to threats: September will go to the Worsted Wood and fetch what she finds in a casket there, or else.

But September will also have to stop the Marquess, or else, because the Marquess wants to separate Fairyland from our world forever, so no one ever has to miss Fairyland the way the Marquess did. This character in all her incarnations is her own version of the Three Fates: young Maud, who stumbled into Fairyland; grown-up Queen Mallow, who built a city out of cloth but fell back out again; and the Marquess, who clawed her way back and will not be sent home again, not ever. Her adult life was a prize she made for herself, and the rules of Fairyland took it away.

The first lesson of Fairyland is not entirely unlike the first lesson of Labyrinth: Nothing is ever quite what it seems. The Marquess is no villain, because villainy, straight up, is too simple for Valente, who hones in on the place where desires overlap and conflict and change. The Marquess is a different version of who September might have been: a young girl, a reader of stories, bearer of swords, whose story went down a different road. But September, being Somewhat Heartless, is young enough not to listen to her and to choose to do what she thinks is right.

The Girl Who Circumnavigated is all about choosing: The Marquess chooses to fall asleep, like any princess who needs time to stand still for her for a while. September chooses, like she has all along: to take up a quest. To take up a sword. To wrestle Saturday, her friend, who hates fighting people. But defeating him will give her a wish, and she can wish them all safe. It’s a terrible choice, but she chooses it.

And she still has to go home, or she will be no better than the Marquess, who would close off Fairyland to protect her own heart. She will also have to come back, like Persephone, every year. There’s always a catch to saying yes, and this is a good one: She has to come back. Even though she’ll grow up; she’ll care about other things and change and become a different version of herself. She has to come back. Not because she was chosen, but because she said yes.

II: “You can be everything, all at once.”

Partway through Circumnavigated, September makes a choice that has belated consequences. She can’t bear to watch when the Glashtyn, who have the run of the river around Pandemonium, demand a Pooka child as payment for passage. She gives them her shadow instead, watching it pirouette as it heads underground.

Partway through Circumnavigated, September makes a choice that has belated consequences. She can’t bear to watch when the Glashtyn, who have the run of the river around Pandemonium, demand a Pooka child as payment for passage. She gives them her shadow instead, watching it pirouette as it heads underground.

You can’t give up your dark side, however, and shadows have minds of their own.

Fairyland is an underworld already, but it’s underworlds all the way down, and in The Girl Who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revels There, Fairyland-Below has got itself a new, shadow-stealing queen: Halloween, the Hollow Queen, Princess of Doing as You Please, and Night’s Best Girl. She’s September’s lost shadow, and when September returns to Fairyland, a year later, she finds it’s her own broken self that needs fixing.

En route to meeting herself, September encounters the Duke of Teatime and the Vicereine of Coffee, who embody the rituals of certain beverages, the way they set you on your path and start your day; Aubergine, the Night Dodo, who practices Quiet Magic; Belinda Cabbage, who invents the most useful narrative devices; and a grad student in search of a Grand Unified Tale that doesn’t leave anybody out. (There’s also an on-the-nose commentary about princess-searching quests and the dubiousness of just throwing a kingdom at the nearest bit of royalty to wake from a long nap.)

But it’s a Sibyl whose words stay with September through the rest of her adventures, and whose confidence in what she does is the envy of September’s young heart. “Sometimes, work is the gift of the world to the wanting,” says Slant, who offers a choice of faces to different seekers. Between the Sibyl and the peculiar, off-kilter shadows of her friends, September comes to understand the way people are made up of different parts, and don’t show all of them, all the time.

It’s a lesson so many of us take for granted: we contain multitudes! We are not the same person at that fancy cocktail party as we are in pajamas, at home, with a cup of tea! But Valente’s own magic is taking the well-worn tenets of adulthood and twisting them into new shapes, until they look awfully like the laws of magical kingdoms. You need your dark side; you aren’t you without her. And she may be wonderful: Halloween is all the rest of September’s ill-tempered irascibility, gone greedy for love and laughter and magic, with no thought for anyone who doesn’t want to join in.

The dark side is the one with the sly grin, who knows how to throw a party, who isn’t afraid to dance even if everyone’s watching, and who will do anything to keep the people she loves near. Even those of us who bristle at being Sorted into Slytherin can begrudgingly admit that villainy is, by and large, a matter of perspective (with the occasional exceptions). And Fairyland is all about perspective. The Marquess, Halloween—they both want the same thing September wants: for everyone she loves to be close and safe and never taken away.

You will have to forgive yourself for some bad choices, sometimes. And sometimes you need to be sly and slippery. Especially when you’re grown. As the Minotaur says, “The thing to decide is what kind of monster to be.”

III. “Time is the only magic.”

Valente’s intense sympathy for monsters, her appreciation of shadows and misconceptions and uncertainty, come to the forefront in book three, the moody middle child of the series (and my favorite). In The Girl Who Soared Over Fairyland and Cut the Moon in Two, September has to scrabble to get back into Fairyland, and as soon as she does, the Blue Wind is laughing in her face, telling her to stop expecting everyone to be thrilled to see her. She did topple two governments and make an awful mess on her last two trips.

Valente’s intense sympathy for monsters, her appreciation of shadows and misconceptions and uncertainty, come to the forefront in book three, the moody middle child of the series (and my favorite). In The Girl Who Soared Over Fairyland and Cut the Moon in Two, September has to scrabble to get back into Fairyland, and as soon as she does, the Blue Wind is laughing in her face, telling her to stop expecting everyone to be thrilled to see her. She did topple two governments and make an awful mess on her last two trips.

“She who blushes first loses,” the Wind says, and throughout, September struggles to control her growing heart, to present a different face to the world, a cannier face—one that will go nicely with her new clothes. She has, after her previous two visits, been dubbed a criminal. It’s just a matter of perspective, but what isn’t? While she sees herself as the hero of her story, to the current king of Fairyland, Charlie Crunchcrab, she’s a scofflaw, a revolutionary, likely to depose him, too, if he doesn’t watch out.

As it turns out, criminals get wonderful uniforms. (Valente has a great respect for the uses of clothing—not just the magical kind, but the kind that tells people who you want to be today, and how you want to be perceived.) Dressed in silks and driving a Model A that keeps transforming, September heads to the moon, tasked with delivering a mysterious package. She reunites with her friends, but all is not well: A-Through-L is shrinking, and Saturday’s older, larger self is running around, doing things that don’t make any sense. (He’s a Marid; he lives time differently. Also, he’s blue, like a little personable TARDIS.)

But the things older Saturday is doing only don’t make sense from September’s perspective. From the Blue Wind’s needling to a crocodile’s explanation about money magic to Orrery, a city of photographs and lenses, Soared constantly challenges September to look at things differently. A heroine is a criminal. A whelk is a city. Prepositions are magic and nothing but trouble. Saying no is “your first hint that something’s alive.” A cannonball is an expression of love. Princess is a position in the civil service. A moon-Yeti is a midwife.

“Living is a paragraph, constantly rewritten,” the sly narrator, forever telling secrets, assures us. “It is Grown-Up Magic.” This is echoed by the lesson of Pluto, which has two parts:

What others call you, you become.

It’s a terrible magic that everyone can do—so do it. Call yourself what you wish to become.

September doesn’t know yet what she wishes to become. But she wants to choose, and is afraid: afraid that fate has already decided things, and that she won’t have enough time in Fairyland, that books say you can’t go back. But when she admits her fears about growing up and losing Fairyland, her Marid is there to tell her: no. “I am growing up, too,” he says, “and look at me! I cry and I blush and I live in Fairyland always!”

A child might read this literally, in the story, and exult: she can stay, no matter how she grows. She can find her way back, always. An adult might read this and remember: you can cry and blush and change.

IV: “We make our worlds of stranger stuff.”

While book three is a deeply sympathetic story about the frustration of not knowing what you want to be and where you fit in the world, book four is achingly understanding about the frustration of knowing you’re in the wrong place. It’s also an about-face for the series: Not about September, not set in Fairyland, it starts when the Red Wind asks a young troll named Hawthorn if he would like to come with her and be a Changeling.

While book three is a deeply sympathetic story about the frustration of not knowing what you want to be and where you fit in the world, book four is achingly understanding about the frustration of knowing you’re in the wrong place. It’s also an about-face for the series: Not about September, not set in Fairyland, it starts when the Red Wind asks a young troll named Hawthorn if he would like to come with her and be a Changeling.

Hawthorn says yes, and after a delightful aside in which the postal service is revealed to have a magical branch in Fairyland, finds himself transformed into an angry human child whose skin doesn’t fit right, and whose possessions will not talk to him. The will o’ the wisp in the lamp stays silent. The knitted wombat his mother makes him doesn’t growl or bite. And his father keeps insisting he be Normal.

Thomas, who loves his parents even if he insists on driving them crazy by calling them by their first names, tries to make sense of the world by writing down the rules as he sees them—first the rules of the Nation of Learmont Arms Apartments, and then the rules of school, which is a kingdom all its own. At school, he meets a strange girl named Tamburlaine, who becomes his first real friend, and the first person to invite him into her room.

Her magic room. Tamburlaine, whose house is full of books, has figured things out from stories (tricksy things; sometimes they tell the truth, and sometimes they’re full of lies). With her help, Thomas unlocks his own magic, which involves writing things down. Before long, their combined skills transport them back to Fairyland in the company of a gramophone, a wombat, and a rather terrifying former baseball. But while Changelings are supposed to change, they aren’t supposed to come back. It throws things off balance. The mass is wrong.

Good thing there’s a Spinster already working on that equation.

The Boy Who Lost Fairyland is a promise, the way a book is a door, or a house is a world, or an equation (in one chapter title) is a prophecy that always comes true. You can find your people. You can be the strangest troll on the block and still find someone who looks at you and sees the things you cannot.

You also can’t lose your home, not unless you choose to. The people who are home to you will be there, waiting for you to come back. They might even come looking for you, if you’re gone long enough.

V: “Endings are rubbish. … There is only the place where you choose to stop talking.”

The Girl Who Raced Fairyland All the Way Home only just came out, and I don’t want to spoil it for you. At the end of The Boy Who…, a tricky bit of magic brings back every former ruler of Fairyland. The crown chooses September, for the moment, but she has many challengers.

The Girl Who Raced Fairyland All the Way Home only just came out, and I don’t want to spoil it for you. At the end of The Boy Who…, a tricky bit of magic brings back every former ruler of Fairyland. The crown chooses September, for the moment, but she has many challengers.

Even the Marquess is awake again, smiling slyly at September. She couldn’t possibly miss the end.

The Girl Who Raced’s grand race for the crown of Fairyland involves a derby and troublesome odds, a parley and a conspiracy and more than one duel. It’s a book about the fights you can’t win alone and the ones you can, and about the nature and desirability of power. Ruling a place, it turns out, is far more complicated than running off to it. (When Valente mentioned on Twitter that you might want to revisit “The Girl Who Ruled Fairyland for a Little While,” she was dropping some pretty big hints.)

In Alison Lurie’s book Don’t Tell the Grown-Ups, she argues that much of classic children’s literature is subversive: “Its values are not always those of the conventional adult world.” From Wonderland to Never-Never Land to Pooh Corner, children’s books are full of places that reject the values of adults, placing childhood in a superior position. They’re wonderful places, and rejecting or challenging adult values is a vital part of growing up.

But you still have to grow up. And what fun is that, if there is a clear line between young and old, fun and boring, worthwhile and duty-bound? Valente circumnavigates children’s literature, picking and choosing—a knowing narrative voice here; a tea party there; a trip to another planet, a gloriously unlikely magical creature or ten—and loops what she finds into a new kind of subversion: one that says that that growing up can be just as magical and wondrous and strange as anything you find in an Underworld or on the Moon. She disposes with the child/adult dichotomy—

You never feel so grown up as when you are eleven, and never so young and unsure as when you are forty.

One of the awful secrets of seventeen is that it still has seven hiding inside it … This is also one of the awful secrets of seventy.

—and makes September’s adventures, her growing up, the process of making yourself bigger, like the Whelk of the Moon, which just keeps growing to make safe all the things it cares about. Growing up is its own kind of magic: more understanding, more knowledge, more meaning, more and different kinds of love. It’s meeting another part of yourself, like meeting Saturday when he is out of time, but slowly, step by step. All children are Changelings, and all Changelings do what it says on the tin: they change.

The tragedy of Mallow, the Marquess’s former self, is what sets so much of this tale in motion, and it isn’t that she grew up; it’s that she got sent back to childhood without her supper. She had all her changes taken away in a move that demonstrates that childhood is not inherently better, or more magical, than adulthood. It’s a time to explore, literally and emotionally, just as September explores the landscape of Fairyland in the first book, the landscape of dark sides in the second, and the landscape of uncertainty in the third. In the fourth, she’s just offstage, learning to understand Fairyland, while different children, their stories just as important, step into the spotlight.

The fifth book is a tricksy beast. It’s a competition that doesn’t initially make sense, possibly with an unwinnable goal, full of riddles, and September isn’t so much sure that she wants to win as she is certain she doesn’t want some other people to.

Doesn’t that sound more than a little bit like life?

I don’t mean to make it sound as if the Fairyland books are a good-for-you platter of sweets, all with a sneaky terrible, adulthood-hoorah! filling. What I am trying to say is that there is true and joyful subversiveness in a children’s book—a fairy story!—that makes the argument that growing up doesn’t have to mean outgrowing. Fairyland is full of functional, happy, grown, magical creatures—men and women, cuttlefish and Marids, Walruses and Sibyls and Trolls—who are adept at their own grown-up magic.

Some of that magic is work—a thing that Valente, in the middle of some of her own most magical work, sees with a particular clarity. “I want to keep being myself and mind the work that minds me. Work is not always a hard thing that looms over your years,” Slant, the Sibyl, says to 13-year-old September in Fell Beneath as she combs the sunlight out of September’s hair. September has just started to think about who she will be, and what that means, and as the books continue, those thoughts get less sure. It’s what Soared Over in particular is about: Who am I, and who will I be? Who are other people, and how did they figure themselves out? Is my fate decided? If so, is that certainty, or fear?

Oh, September. The magic is always that you choose. In Fairyland, Valente presents a whole new host of choices, giving us characters who travel widdershins against limiting conventional values. Being nice will not always get you there; neither will going along with things, or believing that you alone can tug yourself up by your bootstraps. You might need a Watchful Dress or a criminal’s silks. You might need to argue, when you find someone who loves arguing, or learn to hear an insult as love, or see a world’s broken bits as beautiful.

Quite a few children’s books these days claim they are for all ages. They say things like “For ages 9 to 99” on the flaps, and seem a little bit abashed about possibly being just for children, though there is nothing wrong and about 76 things right with that. But the Fairyland books are for all ages in a very honest way: you can start reading them when you’re younger than September, but if you continue reading them, as you grow, they will remain relevant, and you will never feel like you’re trespassing on a playground of too-small swings. To say that they are the story of growing up is too broad, but also true. The trials September faces and the adventures that draw her in are huge and life-changing, but they always leave her room to wonder about herself and her place in the world. When she meets the Sibyl, she wonders what she will be; when she races for the crown of Fairyland, she thinks, “If I were Queen, I could stay.” But there are plenty of people in Fairyland who are not the queen. You don’t have to be the boss, the one in power, to find the life that suits you.

And there is always power in No Magic and Yes Magic, in accepting your villains and shadows, in sitting down to tea with the people you’re not entirely certain you should trust. September’s story and the Marquess’s story never fully separate, and it takes both kind of magic to get to the end. But it is not spoiling anything to tell you that the last words in this series are exactly the words they should be.

Molly Templeton can’t quite believe she wrote this whole piece without talking about A-Through-L, and she apologizes to Wyverary fans everywhere. She is Tor.com’s publicity coordinator, and can also be found on Twitter.