Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

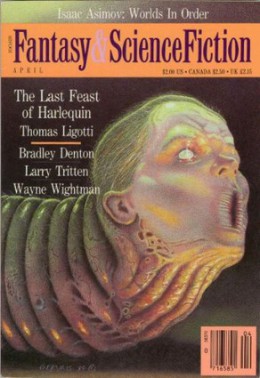

Today we’re looking at Thomas Ligotti’s “The Last Feast of Harlequin,” first published in the April 1990 issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction. You can find it in the Cthulhu 2000 anthology, among other places. Spoilers ahead.

“When he swept his arm around to indicate some common term on the blackboard behind him, one felt he was presenting nothing less than an item of fantastic qualities and secret value. When he replaced his hand in the pocket of his old jacket this fleeting magic was once again stored away in its well-worn pouch, to be retrieved at the sorcerer’s discretion. We sensed he was teaching us more than we could possibly learn, and that he himself was in possession of greater and deeper knowledge than he could possibly impart.”

Summary

Unnamed narrator, a social anthropologist, first hears of Mirocaw from a colleague who knows of his interest in clowns as cultural phenomenon. Apparently this Midwestern town hosts an annual “Fool’s Feast” in which clowns take a prominent part. Narrator not only studies these things, but is proud of being an “adroit jester” himself.

On impulse, he visits Mirocaw. The town’s topography is broken up by internal hills—buildings on hillsides seem to float above lower ones, giving the impression of things askew, tilted, “disharmonious.” An old man, vaguely familiar, ignores his request for directions. A woman at city hall gives him a flyer begging people to “please come” to Mirocaw’s Winter Festival, December 19-21. Reluctantly she admits it features people in…costume, clowns of a sort.

Leaving, narrator passes through a slum peopled by lethargic and morose-looking individuals. He’s glad to escape to the wholesome farmlands beyond.

His colleague locates an article about the “Fool’s Feast.” It’s titled “The Last Feast of Harlequin: Preliminary Notes on a Local Festival.” The author is Raymond Thoss, narrator’s former professor, whom he revered as a lecturer and fieldworker par excellence. Some claimed Thoss’s work was too subjective and impressionistic, but narrator believed him “capable of unearthing hitherto inaccessible strata of human existence.” The “Harlequin” article confuses narrator with its seemingly unrelated references to Poe’s Conqueror Worm, Christmas as descendant of the Roman Saturnalia, and Syrian Gnostics who thought angels made mankind but imperfectly. Their creatures crawled like worms until God set them upright.

Thoss vanished twenty years before. Now narrator realizes where his hero went—wasn’t he the old man in Mirocaw, who ignored narrator’s request for directions?

Narrator learns that Mirocaw is subject to “holiday suicides” and disappearances, such as that of Elizabeth Beadle a couple decades before. Thoss thought there was a connection between the town’s epidemic of Seasonal Affective Disorder and the festival. Narrator himself suffers from wintertime depression—perhaps participation in Mirocaw’s “Fool’s Feast” can lift his spirits as well as further his clown studies.

He arrives to find the town decked in evergreens, green streamers and green lights—an “eerie emerald haze” permeating the place. At his hotel he meets the younger likeness of Elizabeth Beadle; she turns out to be the missing woman’s daughter, Sarah. The hotel owner, her father, evades questions about the festival.

The next morning narrator spots Thoss in a crowd and pursues him to a dingy diner in the southern slum. Two boys flee looking guilty. The rest of the occupants look like empty-faced, shuffling, silent tramps. They surround narrator, who falls into a mesmeric daze. Panic supplants his inertia and he escapes.

That night Mirocaw’s festival begins. People, many drunk, swarm the green-lit streets. Among them are clowns whom the rowdier elements abuse at will. Narrator questions young male revelers about the sanctioned bullying and learns that the townspeople take turns playing “freaks.” They’re unsure what the custom means. Narrator spots a strange “freak,” dressed like a tramp, face painted into a semblance of Munch’s famous “Scream”-er. There are a number of these “Scream” freaks. Narrator pushes one, then realizes that’s a no-no, for no one laughs. In fact the crowds avoid the “Scream” freaks, who seem to celebrate their own festival within the festival. Narrator wonders if the normal folks’ festival is designed to cover up or mitigate the pariahs’ celebration.

Next day he finds a riddle scrawled on his mirror with his own red grease-paint: “What buries itself before it is dead?” Shaken but determined not to abandon his research, narrator makes himself up like a “Scream” freak and plunges into the festivities of the Winter Solstice. Normals avoid him now—he might as well be invisible. His “Scream” fellows pay him no attention either, but allow him to get aboard the truck that comes to pick them up.

It takes them deep into the woods outside town, where lanterns light a clearing with a central pit. One by one the “Scream” freaks drop into the pit and squeeze into a tunnel. Narrator enters near the rear of the pack and finds the tunnel weirdly smooth, as if something six feet in diameter burrowed through the earth.

The crowd ends up in a ballroom-sized chamber with an altar at the center. Thoss, clad in white robes, presides. He looks like a “god of all wisdom,” like Thoth in fact, the Egyptian deity of magic, science and judgment of the dead. Thoss leads the worshippers in a keening song that celebrates darkness, chaos and death. Narrator pretends to sing along. Does Thoss look at him knowingly? Thoss whisks away the altar covering—is that a broken doll?

The worshippers start dropping to the cavern floor. They writhe, transforming into great worms with proboscis-like mouths where faces should be. They squirm toward the altar, where the “doll” awakens to scream at their approach. It’s Sarah Beadle, the Winter Queen, sacrifice to the forces of the underworld, as her mother Elizabeth was two decades earlier.

Narrator runs for the tunnel. He’s pursued, but then Thoss calls the pursuers back.

Narrator leaves Mirocaw the next day, but not before seeing Thoss and another “freak” in the road behind him, merely staring.

Unable to return to teaching, he writes down his experiences in hopes of purging them. No such luck. Thoss’s last words echo in his mind, for Thoss did recognize him, and what he called to the “freak” pursuers was “He is one of us. He has always been one of us.”

But narrator will resist his “nostalgia” for Mirocaw. He will celebrate his last feast alone, to kill Thoss’s words even as they prove their truth about humanity, about the Conqueror Worm.

What’s Cyclopean: Adjective of the day is “epicene,” a descriptor for one of the slum-dwellers along with “lean” and “morose.” Means androgynous, only not in a good way.

The Degenerate Dutch: “Harlequin” inverts the usual sources of eldritch rituals by explicitly denying rumors that the festival is an “ethnic jamboree” with Middle Eastern roots. The citizens of Mirocaw are “solidly Midwestern-American,” whatever that means.

Mythos Making: Al-Hazred had a thing or two to say about worms and magery. And Lovecraft himself had a thing or two to say about the ancient horrors of New England.

Libronomicon: Peer reviewers, let this story stand as a warning. Only you have the power to prevent creepily vague academic articles.

Madness Takes Its Toll: This week, madness takes the form of Seasonal Affective Disorder, in all its holiday-ruining glory.

Anne’s Commentary

Oh, Mirocaw, where are you? The only Mirocaws I find online are Ligotti’s apparent invention and a Star Wars Expanded Universe ship, belonging to a very naughty bounty hunter. We do know we’re in the Midwest and there are sunny farms and fields. I’m guessing Iowa, or else Sinclair Lewis’s equally mythical Winnemac. What fun if Lewis’s Babbitt were to wander into Mirocaw during the winter fest, looking to buy up derelict properties in the southern slum. Or for Elmer Gantry to preach to its pulpy denizens. Or for Arrowsmith to try diagnosing their singular languor…

Ligotti dedicated “The Last Feast of Harlequin” to Lovecraft, and I’m pretty sure Howard would have been gratified. The story makes sincere (rather than satirical) use of Mythosian tropes and weaves echoes of Lovecraft’s “Festival” and “Shadow Over Innsmouth” into a superb tale of nauseous terror—“nauseous” being a compliment here. Worms are just icky, aren’t they? Especially the maggoty ones, all pale and squishy and ravenous. Much worse are humans with wormy characteristics: faces mask-like in their lack of expression, wavering locomotion, and general flaccidness. And what would worms sound like if they could sing? Yep, like Ligotti’s “freaks,” all high and keening, shrill and dissonant and whining.

Ew. Ew, ew.

It’s interesting how one (non-Mirocavian) journalist mistakes the town’s community as Middle Eastern, when in fact Mirocaw’s founders were New England Yankees. But maybe they were New Englanders descended from the “dark furtive folk” who enacted unhallowed rites in “Festival’s” Kingsport. And maybe that “dark furtive folk” were descended from Professor Thoss’s Syrian Gnostics. And maybe among the books and papers in that dim slum diner are transcripts from Alhazred. You know, like, “For it is of old rumour that the soul of the devil-bought hastes not from his charnel clay, but fats and instructs the very worm that gnaws; till out of corruption horrid life springs, and the dull scavengers of earth wax crafty to vex it and swell monstrous to plague it. Great holes secretly are digged where earth’s pores ought to suffice, and things have learnt to walk that ought to crawl.”

In Lovecraft’s story, the narrator never makes it to the climax of the Kingsport winter festival. Ligotti’s narrator, social anthropologist that he is, lingers to hear the fat lady sing, or rather, to see the fat worms writhe toward the sacrificial virgin. He’s not necessarily a lineal descendant of the celebrants, as Lovecraft’s narrator is, but he is their spiritual kin, prone to winter depressions, eager to emulate Thoss in “unearthing hitherto inaccessible strata of human existence.” Ligotti’s narrator is fascinated by the “protean” figure of the clown, has played the clown himself, understands that clowns were frequently cripples, madmen and other “abnormals” forced to take on comic roles so they wouldn’t distress “normals” by embodying the “forces of disorder in the world.” Or else clowns might do the opposite—like Lear’s fool, they might point to those forces of disorder, unwelcome prophets.

No wonder Ligotti’s narrator is drawn to clowns. He might have tried to be a jolly fool, an adroit juggler, but he ends up in the “Scream” freak makeup, one of Thoss’s “us.”

Mirocaw has its pariah slum. Innsmouth is a whole town of pariahs. Both towns also have “normals” who are afraid to interfere with the “abnormals.” The “normals” keep their mouths shut. They blink at the periodic disappearances of young people. Mirocaw is more chilling than Innsmouth in that its “normals” seem to dominate, to keep the “abnormals” at bay, confined, their feast glossed over by a simultaneous “normal” celebration. But the “normal” celebration still provides the “abnormal” one with its sacrifice, the Winter Queen. It attacks only the fake “freaks,” for it cannot even acknowledge the presence of the true ones.

Like “Innsmouth’s” narrator, “Harlequin’s” realizes he belongs among the monsters, for he is one of them. Unlike “Innsmouth’s” narrator, he hasn’t gotten over his horror at his heritage by story’s end. He’s with “Dagon’s” narrator—suicide’s the only relief for unbearable knowledge. His final feast will be poison, I guess. Or maybe not. In the end, the draw of Mirocaw may prove as strong as that of Innsmouth.

Although, got to say, Mirocaw doesn’t have the undersea allure of Y’ha-nthlei. It’s not a place of eternal glory but one of eternal darkness, a “melancholy half-existence dedicated to the many forms of death.” It does have the annual human sacrifice, its own never-rescued Persephone. Exactly what happens to poor Sarah and the others, we don’t see. Apparently the bodies of holiday “suicides” are often discovered in a lake outside Mirocaw, which implies that the worms don’t always devour their victims. That the worms have “proboscises” they seem intent on applying to the “Winter Queen” more than hints at sexual atrocities, “perverted hopes.” [RE: Thanks a lot, Anne—until you brought it up, I totally managed to avoid going there. I just assumed they were sucking out souls or something. Mirocaw honestly seems more likely to shelter dementors than Fager’s passion-fanning furies.]

Again, ew. Ew, ew.

I think I’ll take my winter vacation neither in Kingsport nor Mirocaw. Deep undersea, Y’ha-nthlei is glorious all year round, or so I’ve heard.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Brrr. Ligotti takes a bunch of things that I don’t normally find scary—clowns, winter holidays, the dark of the year—and makes them freaking terrifying. He may have just ruined my next circus.

Clowns, as our academic narrator points out, have a long and darkly ambivalent history. They’re outlet and scapegoat for the socially unacceptable. They’re masks that both permit and require people to take on new roles. And in Shakespeare or a tarot deck, they’re the wise fool: saying or doing what no one else dares, and risking all for that truth. At the same time, they’re inherently duplicitous. Paint hides true reactions, covering smug amusement with exaggerated tears, or terror with a bright smile. Perhaps that’s why clowns have long been a favored form for monsters.

For our narrator, clowns offer both scholarly interest and an escape in their own right. This is shifty by the standards of academic culture—the anthropologist is expected both to immerse and remain aloof, certainly never to fully identify with the thing they study. People risk tenure over this sort of thing. Some activities are appropriate objects of study, and some appropriate hobbies for western academics, and never the twain should meet.

He walks this same line as a narrator. On the one hand he’s the detached scholar, just in town to add another reference to his research. He’s kin to Lovecraft’s Miskatonic profs in this, reporting on the scary as an outsider, coming home with a handful of dread notes and a few new nightmares. But this is only his clown make-up: he’s also in town to track down a beloved professor whose charisma and excitement he’s long internalized. And deeper and more personal still, to fight his own inner demon face to face. For him, that’s a harsh form of the Seasonal Affective Disorder that afflicts so many people when the days grow short.

With personal investment masked by academic disinterest, he stands in sharp contrast to the narrator of “The Festival,” a story that “Harlequin” closely mirrors. The “Festival” narrator’s motivations are overtly personal. He seeks long-lost relatives and an ancestral celebration in a place he’s never before visited. But he never truly connects—as soon as he’s in town, he feels nothing but dread and disgust towards his hosts. When he flees, he flees to safety, with the worst aftereffect being the Necronomicon’s unwelcome hints about his would-be relations.

In “Festival,” it’s what’s under the mask that terrifies: worms grown fat on the flesh of his ancestral wizards, now trying to carry on otherwise dead traditions. In “Harlequin,” seeking wisdom and magic causes people to, um, turn into worms. It’s not so clear what Thoss/Thoth gets out of that transformation, but clearly the sacrifice meets with his approval.

Somehow the narrator’s seasonal depression, and the apparently depression of the “slum” dwellers, are tied up in this search for wisdom. At some level they’re one and the same, leading to the same dreadful end. As in “Shadow Over Innsmouth,” there’s only one way to avoid that transformation. I have to admit, the transformation in “Shadow” seems much more pleasant. But perhaps there is wonder and glory under the earth in Mirocaw, that we never get the chance to see.

Next week, a seaside vacation may not provide the most ideal artistic inspiration in Lovecraft and R. H. Barlow’s “The Night Ocean.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.