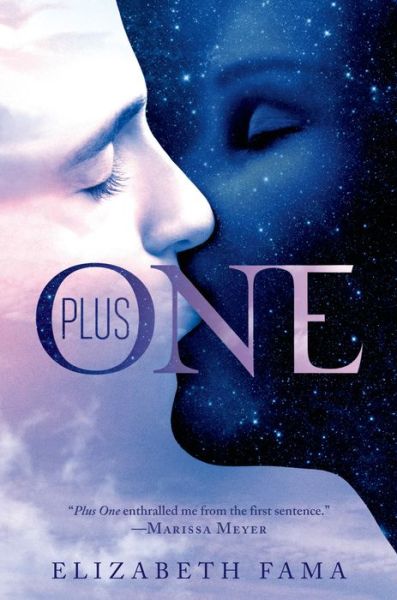

Check out Elizabeth Lama’s Plus One, a fast-paced romantic thriller available April 8th from Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Seventeen-year-old Soleil Le Coeur is a Smudge—a night dweller prohibited by law from going out during the day.

When she fakes an injury in order to get access to and kidnap her newborn niece—a day dweller, or Ray—she sets in motion a fast-paced adventure that will bring her into conflict with the powerful lawmakers who order her world, and draw her together with the boy she was destined to fall in love with, but who is also a Ray.

Wednesday

4:30 a.m.

It takes guts to deliberately mutilate your hand while operating a blister-pack sealing machine, but all I had going for me was guts. It seemed like a fair trade: lose maybe a week’s wages and possibly the tip of my right middle finger, and in exchange Poppu would get to hold his great-granddaughter before he died.

I wasn’t into babies, but Poppu’s unseeing eyes filled to spilling when he spoke of Ciel’s daughter, and that was more than I could bear. It was absurd to me that the dying should grieve the living when the living in this case was only ten kilometers away. Poppu needed to hold that baby, and I was going to bring her to him, even if Ciel wouldn’t.

The machine was programmed to drop daily doses of Circa-Diem and vitamin D into the thirty slots of a blister tray. My job was mind-numbingly boring, and I’d done it maybe a hundred thousand times before without messing up: align a perforated prescription card on the conveyor, slip the PVC blister tray into the card, slide the conveyor to the right under the pill dispenser, inspect the pills after the tray has been filled, fold the foil half of the card over, and slide the conveyor to the left under the heat-sealing plate. Over and over I’d gone through these motions for hours after school, with the rhythmic swooshing, whirring, and stamping of the factory’s powder compresses, laser inscribers, and motors penetrating my wax earplugs no matter how well I molded them to my ear canal.

I should have had a concrete plan for stealing my brother’s baby, with backups and contingencies, but that’s not how my brain works. I only knew for sure how I was going to get into the hospital. There were possible complications that I pushed to the periphery of my mind because they were too overwhelming to think about: I didn’t know how I’d return my niece when I was done with her; I’d be navigating the city during the day with only a Smudge ID; if I was detained by an Hour Guard, there was a chance I’d never see Poppu again.

I thought Poppu was asleep as I kissed him goodbye that night. His skin was cool crepe paper draped over sharp cheek bones. I whispered, “Je t’aime,” and he surprised me by croaking, “Je t’adore, Soleil,” as if he sensed the weight of this departure over all the others.

I slogged through school; I dragged myself to work. An hour before my shift ended, I allowed a prescription card to go askew in the tray, and I poked my right middle finger in to straighten it before the hot plate lowered to seal the foil backing to the card. I closed my eyes as the press came down.

Even though I had only mangled one centimeter of a single finger, my whole body felt like it had been turned inside out and I’d been punched in the heart for good measure. My fingernail had split in two, blood was pooling through the crack, and I smelled burned flesh. It turns out the nerves in your fingertip are ridiculously sensitive, and all at once I realized mine might be screaming for days. Had I thought through this step at all? Would I even be able to hold a baby?

I collapsed, and I might have fainted if the new girl at the machine next to mine hadn’t run to the first-aid station for a blanket, a gauze tourniquet strip, and an ice pack. She used the gauze to wrap the bleeding fingertip tightly—I think I may have punched her with my left fist—eased me onto my back, and covered me with a blanket. I stopped hyperventilating. I let tears stream down the sides of my cheeks onto the cement floor. But I did not cry out loud.

“I’m not calling an ambulance,” the jerk supervisor said, when my finger was numb from the cold and I was able to sit up again. “That would make it a Code Three on the accident report, and this is a Code One at best. We’re seven and a half blocks from the hospital, and you’ve got an hour before curfew. You could crawl and you’d make it before sunrise.”

So I walked to the emergency room. I held my right arm above my head the whole way, to keep the pounding heartbeat in my finger from making my entire hand feel like it would explode. And I thought about how before he turned his back on us, Ciel used to brag that I could think on my feet better than anyone he knew.

Screw you, Ciel.

Wednesday

5:30 a.m.

The triage nurse in the ER was a Smudge. The ID on her lanyard said so, but politely: Night nurse. She had clear blue eyes and copper hair. She could have been my mother, except my eyes are muddier, my hair is a little more flaming, and my mother is dead. I looked past her through an open window into the treatment area. A doctor and her high school apprentice were by the bedside of another patient, with their backs to us.

“Don’t you need to leave?” I asked the nurse, wanting her to stay.

“Excuse me?” She looked up from my hand, where she was removing the blood-soaked gauze.

“I mean, hasn’t your shift ended? You’re running out of night.”

She smiled. “Don’t worry about me, hon. I have a permanent Day pass to get home. We overlap the shifts by an hour, to transition patients from the Night doctors and nurses to the Day staff.”

“A Day pass, of course.” My throat stung, as if I might cry with joy that she’d be nearby for another hour. As if I craved protection, someone who understood me. I made a fist with my left hand under the table, digging my nails into the palm of my hand. Don’t be a coward.

I tipped my head lightly in the direction of the doctor and the apprentice. “Are they Smudges or Rays?”

“They’re Rays,” she said without looking up.

The pressure of the bandage eased as she unwrapped it, which was not a good thing. With no ice pack, and with my hand below the level of my heart for the examination, the pain made me sick to my stomach.

Her brow furrowed when she got the last of the gauze off. “How did you say this happened?”

Of course, from the doctor’s point of view, the accident was more than plausible because I’m a documented failure. It says so right in my high school and work transcripts, which are a permanent part of my state record and programmed into my phone along with my health history. Apprenticeship: Laborer. Compliance: Insubordinate. Allergies: Penicillin. The typical Ray, which this stuck-up doctor was, would never think twice about an uncooperative moron of a Smudge crushing her finger between the plates of a blister-pack sealer, even if it was a machine the Smudge had operated uneventfully for three years, and even if the slimy supervisor had forced her to take a Modafinil as soon as she swiped her phone past the time clock for her shift, dropping the white tablet into her mouth himself and checking under her tongue after she swallowed.

I was lying on a cot with my hand resting on a pull-out extension. The doctor was wearing a lighted headset with a magnifying monocle to examine my throbbing finger. She and her apprentice both had the same dark brown hair; both were wearing white lab coats. I bit my lip and looked at the laminated name tag dangling around her neck to distract myself from the pain. Dr. Hélène Benoît, MD, Day Emergency Medicine. There was a thumbnail photo of her, and then below it in red letters were the words Plus One.

“Elle est sans doute inattentive à son travail,” the doctor murmured to the boy, which means, She undoubtedly doesn’t pay attention to her work. “C’est ainsi qu’elle peut perdre le bout du majeur.” She may lose the tip of her finger as a result.

I thought, Poppu is from a French-speaking region of Belgium, and he raised me from a toddler, you pompous witch. I wanted to slam her for gossiping about me—her patient—to an apprentice, but I kept quiet. It was better for her to think the accident was because of laziness.

“Could I have a painkiller?” I finally asked, revealing more anger than I intended. They both looked up with their doe eyes, hers a piercing gray-blue and his hazel-brown.

Yes, there’s a person at the end of this finger.

Seeing them like that next to each other, eyebrows raised at fake, worried angles, I realized that it wasn’t just their coloring that was similar. He had the same nose as her. A distinctive, narrow beak. Too big for his face—so long that it lost track of where it was and turned to the side when it reached the tip, instead of facing forward. He had her angular cheekbones. I looked at the ID on his lanyard. D’Arcy Benoît, Medical Apprentice. His photo made him look older, and below it was that same phrase, Plus One. He was both her apprentice and her kid.

“Which anesthesia is appropriate in such cases?” She quizzed him in English with a thick accent.

“A digital nerve block?” He had no accent. He was raised here.

She nodded.

The boy left the room and wheeled a tray table back. It had gauze pads, antiseptic wipes, a syringe, and a tiny bottle of medicine on it. He prepped my hand by swabbing the wipe in the webbing on either side of my middle finger. He filled the syringe with the medicine and bent over my hand.

“Medial to the proximal phalanx,” she instructed, her chin raised, looking down her nose at his work. He stuck the needle into the base of my finger. I gasped.

“Sorry,” he whispered.

“Aspirate to rule out intravascular placement,” his mother instructed. He pulled the plunger up, sucking nothing into the syringe. Tears came to my eyes. He pushed the plunger down, and the cold liquid stung as it went in.

“One more,” he said, looking up at me. He was better than his mother at pretending to care.

“Kiss off,” I said. He looked stunned, and then he glared. He plunged the needle into the other side of my finger, with no apologies this time.

“Donne-lui aussi un sédatif,” his mother said, cold as ice. Give her a sedative. Apparently I needed to be pharmacologically restrained.

To me she said, “What is your name?”

“It’s on the triage sheet, if you bothered to read it,” I said.

The boy took my phone from the edge of the cot.

“Hey—” I started.

He tapped the screen. “Sol,” he told her. “S-O-L.” He looked at me pointedly. “Is that even a name?”

I snatched my phone from him with my good hand. “Sol Le Coeur.” My last name means “the heart” in French, but I deliberately pronounced it wrong, as if I didn’t know any better: Lecore.

His mother said, “You will go for an X-ray and come back here, Miss Lecore.”

Wednesday

6:30 a.m.

The pill they had given me was beginning to kick in. I felt a light fog settle in my mind as the X-ray technician walked me back to the treatment area. The boy was there but his mother was gone. I sat on the edge of the cot, unsteady. My finger was blessedly numb and I was very, very relaxed. I wanted to lie down and go to sleep for the day, but I couldn’t afford to rest: I had to get treatment and somehow find that baby.

After the technician left, the boy rolled the tray table over. There was a sheet and a pen on it.

“I… uh… the triage nurse forgot a release form,” he said. “You need to sign it.”

I looked at the paper. It was single-spaced, fine print, and I was in no condition to read.

“Give me the ten-words-or-less version. I’m not a Legal Apprentice.”

He huffed, as if I were a complete pain in the ass, and then counted on his fingers: “You. Allow. Us. To. Look. At. Your. Medical. Records.” He had nine fingers up.

He did it so quickly I felt a surge of anger at the realization that, yeah, the mama’s boy was smart. I grabbed the pen and said, “Hold the paper still.” I signed my name as if I were slashing the paper with a knife.

He put his hand out. “Now, may I see your phone again?”

I took it from my pocket and smacked it into his palm.

“Thank you.”

He scrolled through. He was looking for something.

“You’re underweight,” he commented. “You should get help for that.”

You’re right, I thought. How about a home healthcare worker, a shop-per, a chef, a housekeeper, and a bookkeeper? Oh, and a genie to make Poppu well enough to eat meals with me again. But silly me: the genie can take care of it all while Poppu and I eat foie gras.

“Are you taking any medications?” he asked, after my silence.

“Guess.”

He looked up at me without lifting his head, as if he were looking over glasses. “Aside from melatonin and vitamin D.”

“No.”

His eyes drifted down to the phone again. “Do you want to think about it?”

“No!”

“It says here you took Modafinil four hours ago.”

I opened my mouth, but nothing came out. He waited.

“I did,” I finally said. I didn’t bother to say it had been forced on me.

“Do you have trouble staying alert?”

The wild child surged in my gut. “It’s repetitive-motion factory work, after a full night of school. I wonder how alert you would be.”

He studied my phone again, his brow furrowed. “Sixteen years old. Seventeen in a few days. You should be acclimated to your schedule, if you’re sleeping enough during the day and taking your CircaDiem.”

I pinched my lips together.

He looked up at me. “So, you can’t stand your job.”

I rolled my eyes and lay down on the bed, staring at the ceiling. I had nothing to say to this guy. All I needed was for him to fix me up enough to be functional. The injury was supposed to be my ticket to the Day hospital, not an opportunity for psychoanalysis by some smug Day boy.

“What did you do wrong to get assigned to labor?”

There was something implied in the question, wasn’t there? He thought I was a thug, with a criminal record, maybe. But I couldn’t think straight. The adrenaline from the injury was gone, and I was feeling woozy from the tranquilizer.

His mother came in, and I didn’t exist again.

“It’s a tuft fracture,” he said to her as they studied the X-ray with their backs to me. “Does she need surgery?”

“Conservative treatment is good enough.”

Good enough for a Smudge, I thought.

“Remove the nail and suture the nail bed,” she went on. “Repair of the soft tissue usually leads to adequate reduction of the fracture.”

I closed my eyes and drifted off as she rattled through the medical details. “Soft-tissue repair with 4-0 nylon, uninterrupted stitches; nail-bed repair with loose 5-0 chromic sutures…”

The boy’s bangs blocked my view of his face when I came to. I had trouble focusing for a minute, and my thoughts were thick. Luckily there was no chance I’d have to talk to him. He was working with such concentration on my finger he hadn’t even noticed that I was watching him. It was sort of touching that he was trying to do a good job with a Smudge, I thought stupidly. But then I realized, who better to practice on?

I closed my eyes. Normally I’d be cooking a late dinner for Poppu at this hour of the morning. Then I would read to him to distract him from the pain, and crawl into my bed with no time or energy left for homework. I sluggishly reassured myself that I had left him enough to eat and drink by the side of his bed. Everything made him sick lately, everything except rice and pureed, steamed vegetables. But what if he had trouble using the bedpan alone?

“Poppu,” I heard myself murmur.

“What did you say?” The boy’s voice was far away.

“Poppu.”

When I awoke again, my finger was bandaged, and the apprentice and his mother were huddled together, whispering in French. I heard the words “la maternité”—the maternity ward—and I allowed my heavy eyelids to fall, pretending to sleep.

“…I’ve had to do this before. It’s a trivial inconvenience.”

“Is the baby being reassigned to Day?” the boy asked.

“The mother is a Smudge.” She said the word “Smudge” in English, and I wondered, groggy, whether there was a French equivalent. “Her son will be a Smudge. Being the Night Minister does not mean she can rise above the law.”

“Of course,” the boy said. “And she wouldn’t be able to raise her own child if he were reassigned to Day.”

There was an uncomfortable pause, as if his observation had taken her aback. “I suppose. Yes.”

“So why are we moving the baby to the Day nursery?”

“She asked for him not to receive the Night treatment. That much influence the Night Minister does have.”

In a moment, I stirred on the gurney and took a deep, sighing breath to announce my return to the conscious world. When I opened my eyes, the boy and his mother were staring at me, standing ramrod straight. The clock over the boy’s shoulder said quarter past eight. I smiled, probably a little dreamily, in spite of everything. It was daytime, and I was out of the apartment. My half-baked plan was succeeding so far, in its own fashion.

An Hour Guard came to the doorway with his helmet under his arm. He had the Official Business swagger that’s so ubiquitous among ordinary people who are granted extraordinary authority.

No, my heart whispered.

“Is this the girl who broke curfew?”

“Pardon me?” the mother said.

I stared at the boy until he glanced my way. You didn’t was my first thought, followed by a swift Why?

He pinched his lips together and looked back at the Guard, who had pulled out his phone and was reading it.

“Curfew violation via self-inflicted wound?”

“Yes, she’s the one,” the boy said. His cheeks had ugly red blotches on them. “Her name is Sol Lecore.”

Plus One © Elizabeth Fama, 2014