“I’d rather be a pig than a fascist.”

Great movie line, or greatest movie line?

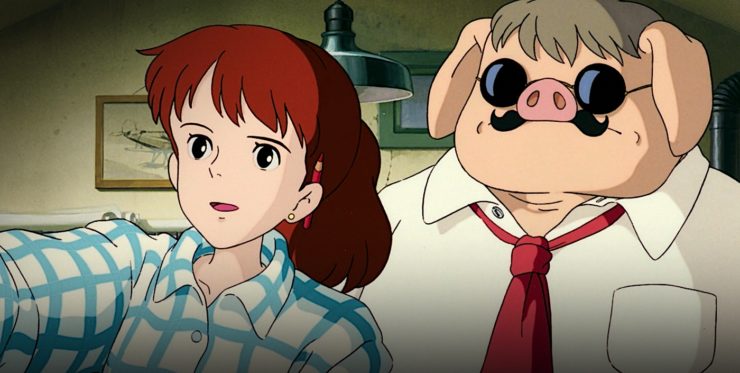

It’s a brief moment in Hayao Miyazaki’s Porco Rosso, when seaplane pilot Marco Rossellini—a man cursed with a pig’s head—meets up with his old pilot buddy Rory. The two have a clandestine conversation in a movie theater, and Rory warns Marco that the Italian Air Force wants to recruit him, and they’re not going to take no for an answer. This scene comes about 40 minutes into the movie; until now, the only stakes were whether Marco would make enough bounties to cover the cost of repairing his plane. But now Marco has a choice to make.

He can join the Italian Air Force, and the war that looms on Europe’s horizon, or he can remain an outlaw, and live with death threats over his head.

He can return to the world of men, or remain a pig.

One of the best things about Porco Rosso is that Miyazaki leaves this choice hanging in the background of every frame of the movie, but he never, never, gives it any real discussion beyond this exchange, because it doesn’t deserve it. Instead he proves the absurdity of fascism by showing us a life lived in opposition to it—a life free of bigotry, authoritarianism, and meaningless bureaucracy.

A life of pure flight.

I have a game I like to play with truly great movies. I try to see the movies they could have been, the choices they could have made that would have made them conventional. Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle could have been a power struggle between the uncle and the dad over the fate of the boy, instead of a story that gently poked at both men’s foibles, and showed that the boy loved them both. Groundhog Day could have opened with that witch’s curse, or ended when Phil gave Rita a perfect romantic day, rather than holding out for an inexplicable time loop and the idea that Phil needs to become a better person before he can go back to life. The Lord of the Rings could have focused on Aragorn’s action-heavy plotline, rather than giving the necessary weight to Frodo and Sam’s slog through Mordor. The Third Man could have gone for the romantic ending, Inside Llewyn Davis could have gone for the triumphant one. Design for Living could have ended with Gilda choosing between George and Tom rather than saying “Both? Both. Both. Both is good.”

And Porco Rosso could have been your basic fairy tale: cursed pig needs true love’s kiss to turn back into a man. Or it could have been about Marco seriously weighing his options with the Italian government, and whether it would be worth it to join the army to save his own skin. It could have been about a love triangle between his childhood friend Gina and the young engineer, Fio—or even just about Gina giving him an ultimatum after so many years.

But this is Miyazaki country, baby. Your conventional storytelling arcs have no place here.

How did Marco become a pig? Don’t know, does it matter?

Why does everyone accept a pig-headed man in their midst? Eh, if they didn’t the story wouldn’t work, just go with it.

Did anyone else become pigs? Was this a plague of some kind? Doesn’t seem like it, and why do you care? We’re focused on this one particular pig here.

What matters to this particular pig, though he doesn’t talk about it much, is the why of his pig-ness, not the how. He was an aviator in World War I—like a lot of Miyazaki heroes he loves flight for flight’s sake, and hates using it in the service of war. He saw many men die, including his childhood best friend Berlini, Gina’s first husband. During the worst dogfight of his life he has a mystical experience. His plane seems to fly itself into a realm of white light, and he watches as plane after plane rises around him to join a seemingly endless band of dead pilots. He sees Berlini, who had married Gina only days before, rising with the rest of the dead. He calls to him, offers to go in his place for Gina’s sake, but his friend doesn’t acknowledge him. When Marco wakes, his plane is skimming over the water, and he’s alone.

As he tells this story to his 17-year-old first-time plane engineer, Fio Piccolo, the implication seems to be that this is when he became a pig, but the interesting thing is that we don’t learn why.

Marco sees his pig-ness as a curse—or really, as a mark of shame. He offered to go in his friend’s place, and instead was sent back to live out his life. His belief that “The good guys were the ones who died” means that in his own eyes, he’s not a good guy. What Fio interprets as “God was telling you it wasn’t your time yet” Marco interprets as “Seems to me He was telling me I was a pig and maybe I deserved to be all alone” or, possibly worse: “maybe I’m dead, and life as a pig is the same thing as hell.”

But everything we see—his care for Fio, his offer to go in Berlini’s place, his refusal to take a lethal shot at a pilot rather than a non-lethal shot at the body of plane—implies that Marco Rossellini’s entire life is informed by a sense of honor and decency, whether he has a pig’s head or not. So why the curse? The movie never quite answers that, it simply takes the curse as a fact and moves on. I have my own ideas, but I’ll get there in a minute.

Having been rejected by God, and set apart from the world of men, what does Marco do?

Does he crawl inside a bottle, become self-destructive, open a bar, star in a play called Everybody Comes To Pig’s?

Nah.

He recognizes his freedom for what it is, embraces it, and seeks joy above all else. His joy, as in most Miyazaki stories, is flight, pure and unfettered, untethered to a military crusade or commercial interests. He chases bounties to make enough money to invest in his plane and buy himself food and wine. He has a couple of outfits so he can look comparatively stylish when he has to go into the city. He lives rough in a sheltered cove so he doesn’t have to bother with landlords or equity. He keeps his overhead low. Unlike Rick Blaine, one of his most obvious counterparts, he doesn’t get embroiled in the hell that is property management. As much as possible, he steers clear of capitalism, which, unsurprisingly, makes it easier for him to reject fascism when it rises, as it always does, and always will.

Porco is a time-tested archetype: the guy who made it through the war but wishes he didn’t. I already mentioned Rick Blaine, but most noir gumshoes, Perry Mason in HBO’s reboot, Eddie Valiant, Harry Lime and Holly Martins—they saw things no one should ever see, they lost friends, they lost their faith in people, science, government institutions, religion, innate human decency. They find themselves in a world they feel out of step with, and have to find a way to make it through each day, while everyone around them seems fine—or at least, they’ve learned to hide the pain better. Some of them inch back toward humanity because of a case they solve, or the love of a good dame, some of them start watering down penicillin. One of the best aspects of Porco Rosso is that Miyazaki never tips the film into the higher stakes of some of the other films in this subgenre. Porco’s chased by the fascist secret police once, but he loses them easily. The Italian Air Force plans to storm the climactic dogfight, but they don’t get anywhere close to catching anyone.

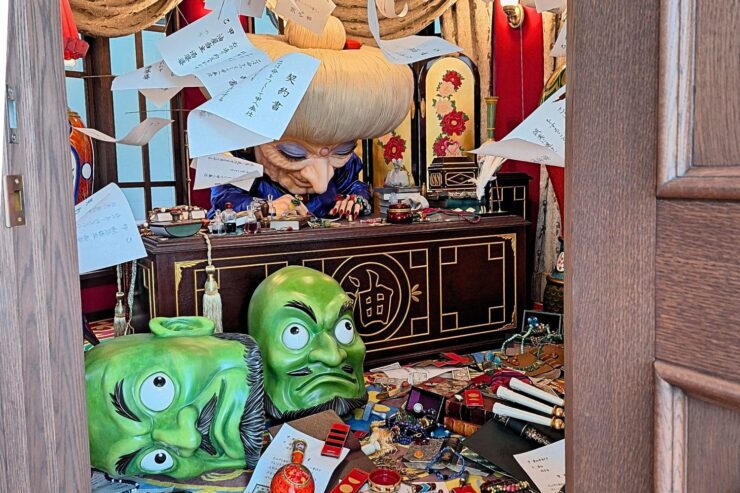

The usual elements that make Miyazaki films a joy to watch are all there. The air pirates, especially the Mamma Aiuto gang, are a source of hilarious slapstick. The group of little girls they kidnap are delightful agents of chaos. When Marco meets his friend Rory in a movie theater, the film they’re watching is a Betty Boop-style animation that is period-accurate for 1929 and adorable. The Adriatic Sea, the cafes, the Hotel Adriano, Gina’s garden—all of them are lush and glowing and like a perfect dream of the Mediterranean. All the elderly men are wizened and deadpan, all the elderly women are sociopaths.

Gina herself is a complex, independent woman with her own life. She runs the Hotel Adriano, sings at the bar, and maintains a secret comms center to keep an eye on the fascists (come to think of it, she’s the better Rick Blaine analogue). All the seaplane pilots are in love with her, and they treat her with utter respect. Fio Piccolo is only 17, but Porco admires her enthusiasm and hires her to rebuild his beloved plane. Like a lot of Miyazaki’s young heroines, she’s consumed by her work. She’s defined as a creator first, and while the film never makes fun of her crush on Porco (in fact, Gina blames Marco for leading her on) it’s also clear that her romantic feelings are an afterthought compared to her journey as an engineer. In fact, Porco Rosso can be read as Fio’s bildungsroman as easily as a story of Marco begrudgingly sidling up to being human again—she’s the one who takes on a new challenge, rises to an opportunity, leaves home, falls in love for the first time, and embarks on what turns out to be her career path. All Marco does is fly really well.

But of course, flight is everything in this movie. It’s a way to make a living, sure, but Porco makes a point of keeping his overhead low, so he can only take occasional gigs to pay for food, liquor, and plane repairs. More important: flight is sex, both in the flashback of young Marco and Gina’s first flight together on the “Adriano” and in the loop-the-loops he does to show off for her years later. Flight is battle in all the dogfights and pursuits between Porco, Curtis, assorted air pirates, and the Italian Air Force. Flight is escape from the society of earthbound men and all of its ridiculous laws. Flight is community, in the Piccolo Airworks, and in the camaraderie between the air pirates, who band together against the tourists and the Italian military. Flight is love, in Porco and Fio’s first flight together, and, again, in all of Marco’s dives and barrel rolls that are the only way he feels eloquent enough to woo Gina. Flight is death and afterlife, in Marco’s vision during The Great War.

But most of all, flight is freedom.

The plot is wisp-thin, because it’s really just an excuse for us to watch planes fly. When Porco’s friend Rory pleads with him to join the Air Force, his reply is succinct. “I only fly for myself.” And as the movie makes clear over and over, this is the point. The movie wasn’t made to give us a convoluted plot, or a modernized fairy tale, or a love triangle, or, at least on the surface, a story about fighting fascism. This movie was made to make us feel like we’re flying. The point of the movie is to watch Porco in his perfect, shining red plane, loop and swirl and dive through clouds, an expression of life and joy. His flight is a repudiation of the horror of the Great War, a fuck you to the fascist government that wants to control him, a laugh in the face of landlocked life. Porco’s world is made of the sea and the sky. It’s controlled by tides, air currents, and clouds. All the illusions of control that are so important to a certain type of human are meaningless here. Even in the final dogfight—the tourists come to watch it like it’s an air show, but at one point they fight swoops down over them, scatters the well-dressed audience, knocks a tower over, blows money away. They’re irrelevant to the real life that’s being lived in the sky. I think it’s also important to note that even when Porco and Curtis land their planes, they fight in waist-deep sea rather than retreating all the way to the beach.

My theory about why Marco became a pig has always been that he chose his life as a pig, in a violent, subconscious rejection of the society that could result in The Great War. The movie doesn’t quite say that—even Gina refers to Marco’s pig-headedness as a curse he needs to break—but all of Marco’s interactions with regular humans underline the idea. He revels in the fact that humanity’s laws and wars and mores no longer apply to him. The mask only seems to slip twice: once, the night before the dogfight with Curtis, when Fio sees Marco’s face rather than Porco’s, and again after she kisses him goodbye. In both cases it’s the innocent, passionate girl, the one who loves planes and flight, who seems to nudge him toward thinking humanity might be worth a second shot.

Maybe.