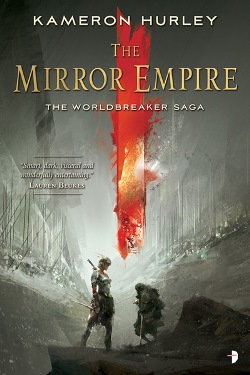

The reality of gender as a tension between socio-cultural constructs and personal identity is rarely as apparent in fiction as it is in The Mirror Empire. In Kameron Hurley’s epic fantasy, the three plot-central countries each have a different gender system: five genders in Dhai, three genders in Saiduan, two genders in Dorinah.

In their differing strengths and flaws—in their multiplicity—they open up the possibility of a rich conversation about gender.

Early in the book, we learn that there are five genders in Dhai—female-assertive, female-passive, male-assertive, male-passive, and ungendered. These are very much socio-cultural constructs, with “assertive” and “passive” seeming to carry connotations similar to their meanings in English, as indicated by Ahkio’s view of himself:

“Ahkio referred to himself with the male-passive pronoun … Ahkio always thought the pronoun very accurate, even complimentary—he was a teacher, a lover, a man who wanted four spouses and dozens of children, but somehow, the way Nasaka said it, it felt like an insult.”

Dhai gender is not much developed beyond this: the female assertive and passive genders are denoted by “she” in the text, and likewise for the male genders, while we never meet an ungendered Dhai. What it means to be ungendered in Dhai culture—why, for instance, there is no assertive-passive distinction for ungendered people—is not mentioned.

In Saiduan, the genders of male, female and ataisa—a word for a third gender that isn’t positioned as “neither male nor female”!—are defined on the basis of sexual organs, with ataisa the apparent gender for intersex people. All three genders have distinct pronouns. In Dorinah, the genders are female and male.

Gendered roles—which are never far from genders—vary, too, from the relaxed culture of Dhai to the segregated culture of Saiduan and what we would consider the role-reversed culture of Dorinah, where women hold the power and men are possessions.

If the lines between the cultures are drawn too neatly at times, it allows the book to show some of the differences and consider how people could navigate them.

“Two green-robed orderlies were helping Luna dress. They pulled Luna’s soiled robe off, revealing his small breasts. Roh was used to Dhai, where everyone chose what gender they went by. He wondered, for the first time, who had decided Luna was not ‘he’ or ‘she’ but ‘ze’. […] But that, it turned out, was a terrible train of thought, because then he had to acknowledge that every single person he’d met in Saiduan had had a gender decided for them. They had no choice in it at all.”

Not subtle—but, yes.

Subtler, and stranger, is the Dhai characters’ use of pronouns to refer to Luna, a Dhai person enslaved in Saiduan and assigned a Saiduan gender.

“Yes, Aramey told me,” Kihin said. “Luna was a Woodland Dhai. Some Dorinah raiding party caught him on the coast and sold him off to the Saiduan.”

“You best be using hir correct pronoun in Saiduan,” Dasai said, in Saiduan.

“I’m not an impolite person,” Kihin said, also in Saiduan. “I’m aware of hir pronoun.”

Luna’s own gender identity is not made clear, although it’s possible that Kihin is expressing Luna’s private preference when talking in Dhai: “They spoke in Dhai, and Kihin used the Dhai male-passive pronoun for Luna, not the Saiduan ataisa pronoun, which Roh thought was interesting.” Whether the Dhai ungendered pronoun—whatever it is—maps onto the Saiduan ataisa pronoun is not stated.

Part of the lack of clarity about ataisa and ungendered Dhai is their relative invisibility in the book compared to female and male characters. Taigan is an uncertain—and magical—exception, with a body that heals almost instantly and cycles between “male” and “female” on its own schedule, beyond Taigan’s control. Taigan, a Saiduan, adapts identity to these bodily changes: “…her sexual organs—let alone her sense of herself—never fit into the three neat boxes her people had for them. Unsure of what to call her, they labelled her ataisa, but that never felt right, either.” Earlier, Taigan longs for a straightforwardly in-between body that might better fit an ataisa identity.

Characters who fall outside their culture’s neat gender systems for non-magical reasons are not in evidence.

Ultimately, The Mirror Empire avoids some of its own complexities. Almost all of the characters are female or male, with the further Dhai distinction between assertive and passive genders rendered near-invisible by the English language’s pronouns. The book confronts, yes, but not too much.

There is a difficult balance to tread between explanation, elision and normalisation of gender. At times, the explanations of gender in The Mirror Empire sit awkwardly in the narrative: the characters would not need to explain their own cultures. We, the readers, need to know—especially readers disinclined to notice subtler suggestions. Elsewhere, I’d have liked to know more about the gender systems—the Dhai five-gender system in particular—and for the people whose genders don’t match our cultural binary to be more visible.

The Mirror Empire is an ambitious book, flawed (in more ways than this) but setting aside the stale defaults that dog so much fiction set in other worlds. If its conversation about gender is more muted that I would like, it is not lacking, either: it presents not a single answer but a human multiplicity, not neatly matched to each other. It makes clear the role that culture plays in constructing gender, but doesn’t forget that innate identity exists in relation to that. I look forward to what we see in Empire Ascendant, out in 2015.

Alex Dally MacFarlane is a writer, editor and historian. Her science fiction has appeared (or is forthcoming) in Clarkesworld, Interfictions Online, Gigantic Worlds, Solaris Rising 3 and The Year’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy: 2014. She is the editor of Aliens: Recent Encounters (2013) and The Mammoth Book of SF Stories by Women (forthcoming in late 2014).

I thought this was a good start to the story and also look forward to how things deapen and get fleshed out in the next book. This book introduced a number of ambitious concepts and Kameron has said about the gender aspects:

in her post at intellectusspeculativus.wordpress.com/2014/09/03/guest-post-beyond-he-man-she-ra-writing-non-binary-characters-by-kameron-hurley/

Nothing to say about Dorinah’s inversion of the patriarchal society?