I’ve been asked a few times, in general or in reference to specific books: what do I think of the depiction of non-binary gender systems in aliens? Though I’ve mentioned it in passing at least once, I realised I’ve never given the question—and its answer—a post of its own.

Alien life—is it out there? what will it look like? what will meeting it be like?—lies at the heart of not only science fiction but the popular imagination, whether in farmer-abducting flying saucers or the real possibility of microbial life in our solar system. I find it fascinating. I edited Aliens: Recent Encounters out of that fascination. In fiction, alien life is a very revealing subject-matter: what is the author capable of imagining beyond the confines of human (and wider Earth) biology and cultures?

The problem is that the “confines” of human cultures are too tightly written.

Simone Nanut put vines down into the body of Golubash. He-She-It bent down very low over Nanut’s hunched little form, arms akimbo, and said to her: “That will not work-take-thrive-bear fruit-last beyond your lifetime.”

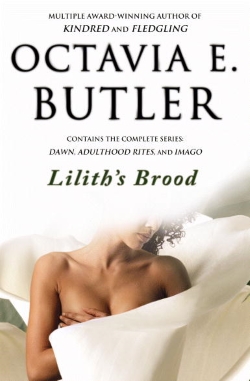

Catherynne M. Valente’s “Golubash, or Wine-Blood-War-Elegy” includes aliens whose continental vastness includes multitudes—including, apparently, of gender. muo-ka of Indrapramit Das’ “muo-ka’s Child” is un-gendered, referred to by the human woman Ziara as “it.” (The pronoun “it” is rarely favoured in real life, as it is widely seen as dehumanising, which raises the question of its appropriateness for sentient alien life. In “muo-ka’s Child,” its use is arguably an unpleasant artefact of Ziara’s hostility to muo-ka.) The amphibian alien ranids in Elizabeth Bear’s Undertow use the pronoun “se.” The oankali of Octavia Butler’s Dawn, Adulthood Rites and Imago (collected as Xenogenesis or Lilith’s Brood), have three genders. Stories of aliens with non-binary biology and/or gender are not too rare, and rightly so: there is no reason for gender systems in alien cultures to be binary. Nor does biology need to be binary, but even if it is, it need not lead to binary gender. I want to see more of these stories.

I want these stories to stop contrasting alien gender systems with the (false) binary gender of humans.

The ability to imagine alien life without human-style (false) binary gender systems (and gender roles) is important. Inability to imagine it points to a great failure of imagination on the writer’s part, one that falls far deeper than the pits of bad fiction. It points to people.

The ability to imagine alien life without human-style (false) binary gender systems (and gender roles) is important. Inability to imagine it points to a great failure of imagination on the writer’s part, one that falls far deeper than the pits of bad fiction. It points to people.

Writing about alien life in science fiction often reflects—by intentional metaphor or not—on how we write about humans (more often about colonialism than about gender, but the erasure of gender from many conversations about colonialism is itself a colonialist act). Do we invade and colonise outer space, or do we work with sentient alien life as equals? Do we respect the local ecologies of non-sentient life? Do we see binary gender everywhere we go? Space is the final frontier on a colonialist map. It is important to think about what we say when we write about alien life.

It is more important, to me, to think about how we write people.

The reality of near-future encounters with alien life is not continental sentiences on other worlds or sudden interventions on ours. If there is microbial life on the icy moons of Enceladus or Europa, it’s unlikely to have gender systems—but the people working at the space agencies that discover this life, if it exists, will not necessarily be binary gendered.

If we meet sentient alien life in the far-future, we will still not be binary gendered.

“But… oh! Listen. Did they just say—”

Hirs turned slowly toward the holocube.

Harrah said at the same moment, through hirs tears, “They stopped dancing.”

Cal said, “Repeat that,” remembered hirself, and moved into the transmission field, replacing Harrah. “Repeat that, please, Seeding 140. Repeat your last transmission.”

Nancy Kress’ “My Mother, Dancing” is an excellent example of an alien encounter story that avoids the default of binary gender in humans. The non-binary pronoun “hirs” might mean a post-binary culture of no genders, one gender, or many genders marked in ways other than pronouns—it is not important to the story to explain the current cultural norm of gender. It is a norm.

This is where my interests lie: the people.

The aliens in “My Mother, Dancing,” meanwhile, are not gendered.

If sentient alien life exists and we meet it and learn that it has gender systems and preferred linguistic markers of gender, we obviously need to respect that—but at this point in time it’s a thought experiment, not a reality. What is a reality—in the past, present and future—is non-binary gender in humans.

My answer to what I think about non-binary aliens is: though I want stories about fictional alien life to avoid the default to binary gender, I want that for humans—here, real—more. It’s more important.

Alex Dally MacFarlane is a writer, editor and historian. Her science fiction has appeared (or is forthcoming) in Clarkesworld, Interfictions Online, Gigantic Worlds, Solaris Rising 3 and The Year’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy: 2014. She is the editor of Aliens: Recent Encounters (2013) and The Mammoth Book of SF Stories by Women (forthcoming in late 2014).