As both a writer and reader I think it’s safe to say that I’ve always learned the most from the books I’ve hated on first reading. Sometimes that lesson has been to avoid a particular author ever after. Other times—and these are the more valuable incidents—I’ve realised I must go back to certain books and read them again. Something, some internal voice far wiser than I, insists, nagging at me until I obey.

These books invariably have one thing in common: they leave a trace in my brain, a hook I simply can’t forget or remove. Something that makes me return to try to figure out what it was that annoyed me so much in the first place. Invariably, again, what I discover is that these books have challenged what I think I know; they shake my long-held beliefs about writing, about history, about literature, about the things I consider to be set in stone. They are tomes that buck the system, flip the bird to my preconceptions, and make me ponder more deeply. They crack open my skull and let light in, they change the way I think—and change is always painful and difficult to accept.

And yet…

I persist in overcoming my natural resistance to change. I go back time and again, initially just trying to pull these tomes apart to see how they tick, to get at the core of what got me so worked up, then later re-reading them once or twice a year because I no longer hate them and, damn, they’re good. Jane Gaskell’s Atlan series was one such experience, John Connolly’s Charlie Parker series is another.

The one that started it all, however, was Kim Newman’s novella Red Reign.

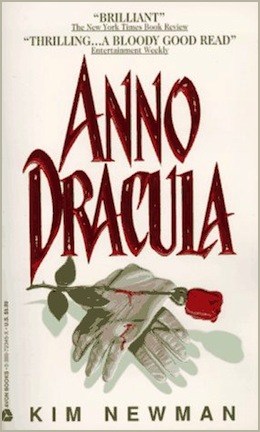

First published in Steve Jones’ The Mammoth Book of Vampires and later expanded into the novel Anno Dracula—read about the novel’s evolution here—Red Reign posits the idea that Dracula won. The Count invaded England, seduced the widowed Queen Victoria, and flooded the UK with his own (hideously corrupted) vampire bloodline. But London is, as ever, adaptable to invaders: the warm and the undead share the city, vampirism is as rife amongst the upper crust as the hoi polloi. Indeed, the vampire state is as much a prerequisite for social climbing as is good lineage, wealth, and knowledge of secret Freemasony handshakes.

The notorious fog allows some older, hardier bloodsuckers to walk during the day. Lords and Ladies pay vampire prostitutes and gigolos to ‘turn’ them. Any dissent is repressed by the Prince Regent’s vicious Carpathian Guard and Bram Stoker’s heroes have, for the most part, become the Count’s lapdogs. Jack the Ripper stalks the streets, hunting not the living but the dead. And nobody, repeat nobody, sparkles.

When I first read this story my mindset was considerably more regimented, my thinking more restricted, and my mind, alas, far narrower than it is today. I threw myself on the fainting couch and sulked. What was this man, this Mister Newman, doing??? Messing with my beloved literature! Taking liberties with past! Not only did he offer an alternative version of history, he had let the bloodsucker win. Well, sort of. And the less said about the breaking of my heart by killing off his superb male lead, Charles Beauregard, the better.

And yet…

I couldn’t get all those what-ifs, all those possibilities, all those alternatives out of my mind. I couldn’t forget the wonderful female lead, Geneviève Dieudonné, a character you want to love and admire and follow—the greatest gift a writer can give a reader. I couldn’t forget the wondrous mix of other dramatis personae, literary and historical, stepping forth re-imagined from the pages, from Sherlock Holmes to George Bernard Shaw, from Dr Jekyll/Mr Hyde to Inspector Abberline, a serpentine weaving and winding across diverse tales and times.

At some point—probably the sixth reading in the space of a month—I realised I didn’t hate Red Reign anymore. I loved it. It was—and still is—an ingenious piece of writing. It was also an astonishing teaching document for a wannabe writer who wasn’t aware at that stage that she was going to be a writer. All that re-reading, all that exploration, examination, and literary autopsying taught me to pick the rich red jewels of craft from its eyes.

Newman’s Red Reign not only let the light in, it taught me to open my mind to possibilities. It showed that received wisdom isn’t all it’s cracked up to be; that the what-ifs are the core of a really compelling tale. It showed how brilliantly deployed ‘clutter’ details can enrich a story as well as providing a cunning hiding place for clues, for the seeds of the tale’s resolution, in plain sight. It’s a textbook example of how to lead a reader into a story by making it appear to be something they recognise before you drop in the world-shaking otherness that says ‘We’re not in Kansas anymore, Toto. Buckle up and pass me a road beer.’

Twenty-one years after that first reading, I’m aware that I used all of Red Reign’s lessons when I wrote Sourdough and Other Stories and The Bitterwood Bible and Other Recountings. Both collections form the basis of the world in which my Tor.com novella, Of Sorrow and Such, is set. So much richness pulled from an initial annoyance! An annoyance for which I’m eternally grateful, for it planted the grit of thought in my mind which subsequent re-readings turned into a pearl of appreciation.

Angela Slatter writes dark fantasy and horror. She is the author of the Aurealis Award-winning The Girl with No Hands and Other Tales, the WFA-shortlisted Sourdough and Other Stories, and the collection/mosaic novel (with Lisa L Hannett), The Female Factory. Her latest novella, Of Sorrow and Such, is available now from Tor.com.