Stanley Kubrick had already well established his reputation as a maverick genius by the time he began work on 1964’s Dr. Strangelove: or How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love The Bomb, as well as his equally powerful reputation for polarizing audiences. Although often named among the greatest American filmmakers, Kubrick has equally vociferous detractors—many of whom were the studio executives who had to sign the checks to pay for his visions and were treated like ATMs for their trouble by the maestro—and even his most ardent defenders (i.e. me from about ages 16-30) have to admit one or two of his features were more interesting than good.

All that equivocation goes out the window when discussing Kubrick’s first semi-foray into science-fiction, though: Dr. Strangelove is one of the greatest movies ever made and that’s all there is to it.

Kubrick, in the process of developing a movie about an accident with nuclear weapons, was given the novel Red Alert by Peter George, a fairly sober thriller on the subject, which he used as the template for his film. While working on the script, though, Kubrick was struck by just how ridiculous the entire situation was, as were the participants themselves and even the Cold War in general. Shortly, the serious-minded Cold War thriller became a jet-black farcical comedy, and Kubrick enlisted satirist Terry Southern to help move the picture in that direction.

What makes Dr. Strangelove work so well as comedy is that the actors—among whose number are some of the finest to ever suit up—play the absurd text, full of references to Burpleson Air Force base, President Murkin Muffley, and a scientist whose name, before he changed it when he became a U.S. citizen, was Merkwürdig Liebe (get it? Das ist, wie “Strange Love” in Deutsch!) totally straight. Kubrick even went to the extent of not telling Slim Pickens, playing the role of bomber pilot Major Kong, that the movie was a comedy so he’d play the role as earnestly as possible. This approach only serves to make everything funnier. Kubrick stages the action on gigantic, almost Expressionistic sets in long takes with the actors’ movements blocked as if they were onstage, further highlighting the unreality, and his touch with it is true enough that it merges with the “straight” acting to hammer home the ultimate point of the absurdity of the Cold War and nuclear escalation.

The story begins with narration referring to rumors that the Soviet Union is at work on a “doomsday device,” a weapon that will kill everything. We’re introduced, then, to Air Force general Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden), who, under an order intended to be used in case of the entire chain of command being eliminated by a Soviet first strike, sends what looks like the entire Air Force to nuke ’em til they glow. His executive officer (Peter Sellers), an RAF captain in an “officer exchange program,” begins to suspect that Ripper might not be in his right mind, largely do to the fact that he isn’t.

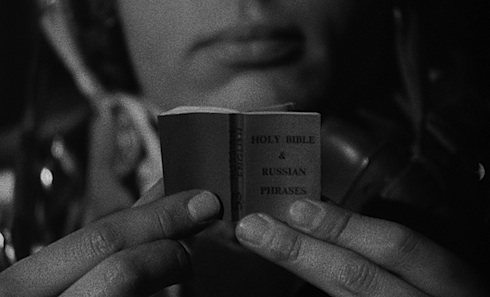

In short order, Air Force General Buck Turgidson (George C. Scott), is summoned to “The War Room” to brief the president (also Peter Sellers) on this situation, leading the president having a couple hilarious phone conversations with a drunk Soviet Premier (reached at his mistress’) about how to deal with the situation. But does their plan take into account the initiative and dogged determination of Slim Pickens and his bomber crew? (One of whom is a very young James Earl Jones, but not so young that he doesn’t have that trademark awesome voice.) And, if all goes horribly wrong and the world is reduced to a lifeless, glowing rock, will the plan cooked up by “ex” Nazi mad scientist Dr. Strangelove (Peter Sellers again) to repopulate the planet with the political and military elite, each of whom will have ten concubines selected for their sexual attractiveness while they spend a century down a mineshaft, work?

Whether it does or not, one thing’s for sure: the movie totally does. It zooms along, its narrative energized by the glorious acting; no matter how over-the-top Sellers, Scott (in particular; his performance is huge), or Hayden get, they never wink at the material, with the possible exception of Sellers’ Strangelove, but by that point everything’s so crazy it’s okay. The ending, which I won’t spoil for anyone who’s yet to see this sprightly, 47-years-young new release, is one of the darkest and funniest ever, and guarantees that you’ll never hear the song “We’ll Meet Again” without seeing Kubrick’s final montage in your mind’s eye. And smile.

Although not SF itself, Dr. Strangelove does hinge on a science-fictional element, the doomsday machine, and like the best SF it’s just plausible enough to give an audience pause. Kubrick made this picture, let us not forget, only a couple years after the U.S. and Soviet Union almost blew each other up over Cuba, and Nikita Krushchev was going to the United Nations while (reportedly) drunk and banging his shoes on lecterns with his hand. The Cold War was insane. But not so insane that some paranoid at the Kremlin or Pentagon wouldn’t build a doomsday device. George Bernard Shaw said, “When a thing is funny, look for the hidden truth,” and this truth isn’t buried all that deeply. Thankfully, thankfully, since the Cold War ran its course to its much-preferred role as ancient history, it’s a lot easier to laugh at Dr. Strangelove now, but we should never forget, Kubrick wasn’t exaggerating all that much. Like his instructions to the cast, sometimes playing it straight is the best satire there is.

Danny Bowes is a playwright, filmmaker and blogger. He is also a contributor to nytheatre.com and Premiere.com.