Forty Thousand in Gehenna (1983) is a book that almost fits into a lot of categories. It’s almost a “wish for something different at the frontier” novel. It’s almost a novel about first contact, It’s almost a generational saga. I always think I don’t like it that much and don’t want to read it, and then I always enjoy it much more than I think I will. This is a strange, complex book—which is true of most Cherryh—and every time I read it I find more in it.

This is a story about an experimental colony that was sent out by one space faction (Union) and abandoned on an insufficiently surveyed planet. The reasons for the abandonment are political and complex, and can mostly be found in Cyteen (1988) rather than here. The colony is designed as an experiment, it’s made up of “born men” and azi—azi are not just clones, not just slaves, but people whose personalities and desires have been programmed and reprogrammed from birth onwards. They’re all sent to Gehenna and left there without help, without further programming, to cope with the aliens and the alien world. Then they’re rediscovered a generation later by a different space faction (Alliance) and studied. This is a story of how they adapt to the world, to the aliens, and to being studied.

Discussion of the book and some unavoidable spoilers.

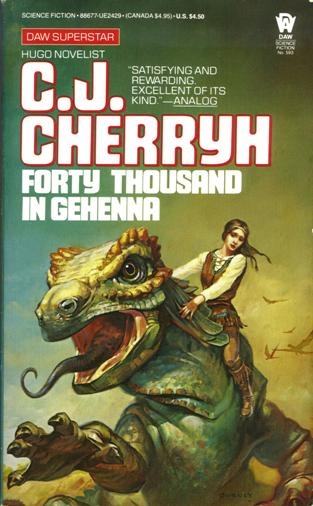

If Forty Thousand in Gehenna were a normal story about colonization, it would have one set of characters and focus on the people. As it is, it has two main sections, with several smaller sections bridging them, and the focus is on the interaction between the characters and the world—including the aliens. The aliens, the calibans, are intelligent but not in the same kind of way as people. They’re some of Cherryh’s best aliens because they are so alien and yet you can, by the end of the book, sort of understand them. But you come to understand them the same way the Gehennans come to understand them, by immersion.

The first section concentrates on the original colonists, born men and azi, and most especially with Gutierrez, the born-man who goes aboard disguised as an azi and is afraid he will be ground down into the mass of them, and Jin, who is azi and is happy with what he is. They make a fine contrast with their very different areas of confidence. Once they get to Gehenna the planet itself starts to throw variables into the plan and things get further and further off track.

Cherryh has written a lot about azi, most of all in Cyteen. Forty Thousand in Gehenna came first, came immediately after Downbelow Station in Cherryh’s exploration of what it means to have a reprogrammable mind. Josh Talley in Downbelow Station has gone through mental upheavals that are hard to imagine. With Jin, Cherryh gives us a character who is supremely sure of his place in the universe, because Tape has told him so, and who is trying to cope in a world that isn’t certain, and with children who are born-men. He wants his known world back again but does his best with the one he has.

The rest of the novel is concerned with his descendants. We know from Cyteen that when an azi has children they teach them interpretively what they understand of their psychset, and here we see it in action. Jin’s descendants learn from him and Pia, and from the calibans. The middle part of the book covers Alliance coming in and meddling and the effects of that, in several choppy chapters from multiple points of view.

The last and longest section is about a war between the descendants of Jin’s daughter and the descendants of his son, and their calibans, and their ways of life. It’s mediated through the scientific memos of the Alliance observers, with their biases and their expectations. This section of the book is absolutely brilliant, and what has been interesting becomes emotionally involving. It’s here we really come to understand the calibans and their way of seeing the world.

Many books are portraits of characters, and more than a few within SF are portraits of worlds. This is one of the very few books I know that is the portrait of a society changing over time and with aliens.

It’s also worth noting that each chapter begins with a list and a map, initially the list of people sent and later a family tree. It’s a small thing but it holds the book together well.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.