Time is a weird thing. Let’s take the year 2007, for example. If you’re anything like me, you’ll first think oh, a few years ago. Then your second thought will be wait, what year is it now? Quickly followed by holy crap, 2007 was thirteen years ago?

I have moments like this every now and then when I realize that time—as it tends to do—marches ever forward, and even now, it’s weird to think we live in the strangely futuristic year of 2020, without flying cars or teleportation, all the things we thought we’d have by now.

Back in 2007, I was twenty-five years old. I was a loud and proud queer dude trying to live my best life. I still am both of those things, though my loudness has lessened with age (or so I tell myself) and my pride is less of a chip on my shoulder—pride, I learned from drag queens, is a riot and we must live in defiance—and more of a state of mind.

Then—as it is now—I looked for queer representation in all forms of media I consumed. From Will & Grace to Queer as Folk and while I appreciated both of them for what they were trying to do, I still felt like they weren’t for me. Books are where I spent most of my time losing myself. That’s always been the case. Ever since I learned to read, I was—and still am—rarely without a book in hand. I tend to shy away from reading digitally, there’s something wonderful about the physicality of turning pages, and the heft of the book, especially longer ones.

My tastes back then were all over the place. I read anything and everything I could get my hands on, searching high and low for queer representation. I could find it in most genres, though the quality ran the gamut from the highest peaks (The Front Runner by Patricia Nell Warren) to the lowest valleys (nah, I’m not going to name names).

One of my first loves was always sci-fi/fantasy. Give me all the gay wizards and witches you can. Let me go along with the queer crew of a ship going into the great unknown, beyond the stars we recognized. Show me queer people doing magic, or fighting dragons, or finding peace and love with an alien species.

Even back in 2007—not too long ago, but also forever ago at the same time—sci-fi/fantasy felt predominantly like a straight white man’s game with straight, white characters to match. I had a hard time finding people like me. There were exceptions to this, of course. Lynn Flewelling’s Nightrunner series featured a queer couple as its main characters (with the sloooowest of burns) that ran over the course of seven books, which I devoured time and time again. It was satisfying and lovely, Ms. Flewelling’s prose taut and exciting, but it only made me want more.

So much so that I asked a librarian friend of mine if she had any suggestions.

She did, in fact. One in particular.

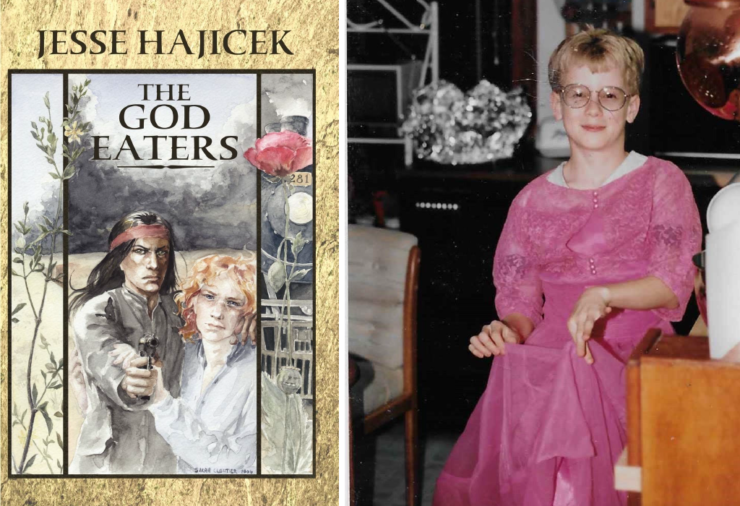

It was by a queer author I’d never heard of before: Jesse Hajicek. She told me to ignore the fact that it’d been self-published, because the book in question was extraordinary. I looked up the author’s bio. The last line read: He was born in 1972 and is still not sorry.

The book?

The God Eaters.

***

Imagine, if you will, a story that is an impossible mixture of Avatar: The Last Airbender by way of X-Men, and Stephen King’s Dark Tower series, with more than a little post-apocalyptic flavor thrown in, and you’ll begin to have the tiniest of inklings at what’s to follow in The God Eaters. Honestly, those ingredients shouldn’t work together. But my god, did Jesse Hajicek find a way to make it one of the best queer reading experiences I’ve ever had, and one that I reread at least once a year.

The story follows Kieran Trevarde and Ashleigh Trine, two young men who, for a bulk of the novel, are on the run. Kieran is a gunslinger who we are introduced to as a child, when he kills another boy who bullied him. Through flashbacks, we see Kieran turn into a Clyde Barrow-like figure with a maybe-more than friend named Shan. Early on, Shan meets his demise and Kieran is captured, sent to a terrible prison with the pointed name of Churchrock.

And it’s here he meets another prisoner: Ashleigh, a young intellectual imprisoned for “inflammatory writings”.

Their time in this prison—which makes up the first quarter of the book—is how I knew I’d found a story to treasure. World-building is one of the most important aspects of writing a fantasy story. While it can have just enough of the real world for the reader to feel a connection, stories in this genre also have their own sets of rules and laws. Poor world-building can create a divide between the book and the reader, because it invites the reader to start poking holes in logic and details.

Hajicek’s world-building is first class. Churchrock—which isn’t, as it seems at first glance—is a terrible, grimy place where prisoners are treated like lab rats, those in power searching for those with abilities called Talents. The abilities range from telekinesis to pyrokinesis, a form of magic that has been outlawed in this world. Those who are found to be Talents in this prison are experimented on. There is, of course, the ultimate baddy who—as the title suggests—decides that eating the powers of others is the only way forward.

The prose is lush and vibrant. I could feel the dirt underneath my fingernails, the way the hot desert wind blew across my face as I journeyed with Ashleigh and Keiran as they plotted their escape. As I mentioned previously, the prison is only the first part of the book, and after a brazen and daring breakout as exciting as anything I’ve read—the world opens up even wider, and turns into a struggle for survival.

And, of course, queer love.

Kieran could have quite easily been a one-note character: hardened and angry at all he’s been through, but Hajicek takes his time, revealing the true depth of Kieran as someone who—while having lost much—is still only nineteen years old. Similarly, Ashleigh is quiet and worrisome, seemingly a doormat at first, but he too grows into himself because the situation he finds himself in demands it. These two people are thrust together—Kieran only dragging Ashleigh along because Ashleigh refuses to be left behind—because of circumstance. But what follows is a slow bloom that turns from begrudging allies to deep friendship, and then even more.

Buy the Book

The House in the Cerulean Sea

And it was here, finally, I got to see myself in a fantasy story: queer people who fight for what they love, leaning on each other even though they don’t know quite how to trust each other, at least at first. It proved to me that queer people didn’t need to be relegated the role of a sidekick or, even worse, instead have the entire arc be mired in tragedy. The story could be centered on people like me, and in a SFF space, that was so very, very important. These characters weren’t extreme charicatures, nor were they set in a story meant to titillate (not that there’s anything wrong with that). What grows between them is the definition of a slow burn, and the reader is better off for it, because it allowed the characters room to breathe and grow and trust in each other. This isn’t erotica. While sex plays a part—both good and bad, Kieran revealing to have sold his body to survive—it’s only part of how Kieran and Ashleigh learn to love each other.

Even better?

It’s a happy ending for them both. Some of you reading this might have rolled your eyes at that, but it’s important. For the longest time, queer characters weren’t allowed to be as happy as everyone else. If we were in a book at all, we were boiled down to stereotypes, sidekicks that served only to advance the straight protagonist. Here, being queer isn’t all Kieran and Ashleigh are. It’s part of them, mixed in with their identity.

Undoubtedly, this has read like a gushing fanboy review. Fair, but I won’t apologize for it. The book was published in 2006. I read it in 2007, and it struck me as hard as any piece of literature I’ve read. Queer voices have risen in publishing these last years, and we’ve carved a place for ourselves in the science fiction/fantasy book community, but we’ve had to fight tooth and nail for a place at the table, much like other marginalized voices have had to. And we won’t let our voices be silenced. Not now. Not again.

Mr. Hajicek hasn’t published much at all that I could find after this book. Which is a damn shame, because voices like his are so, so necessary. If, on the off chance he finds himself reading this, I want to say thank you. Thank you for this story. Thank you for writing the representation you did. We’re all better off for it.

TJ Klune is a Lambda Literary Award-winning author (Into This River I Drown) and an ex-claims examiner for an insurance company. His novels include The House on the Cerulean Sea and The Extraordinaries. Being queer himself, TJ believes it’s important—now more than ever—to have accurate, positive, queer representation in stories.