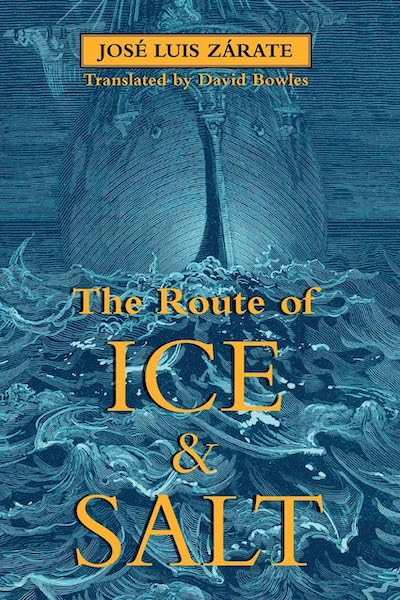

The Route of Ice and Salt, José Luis Zárate’s classic gay novella that retells Dracula’s voyage to England, was originally published in 1998 in Mexico, even though it was translated more recently: the English translation by David Bowles was released in 2021 by Innsmouth Free Press (Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s micro-press) after a successful fundraiser.

I have read various retellings over the years traveling along this route: from Varna to Whitby, the ship named Demeter is transporting the earth in which Dracula rests. I’ve even read other queer ones. But this novella stood out: wonderfully dark prose that undulates like the sea, sensual and sexual and terrifying, pulling me down as I read. The translation was pitch-perfect and poetic. Bowles is in fact a poet, and I appreciated his children’s poetry book They Call Me Güero as well; but here he brings a vastly different tone in translating Zárate’s sexually graphic narrative that at the end even shades into cosmic horror. (I frankly found it more terrifying than the original Dracula, though of course I have the perspective of a century of Dracula-inspired horror.) Bowles also integrates phrasing and word choices from Stoker’s Dracula that Zárate included, translated to Spanish in his novella; the text translated to English thus comes full circle.

The story of the Demeter in Dracula includes ship logs, but here we get both an expanded version of the logs (incorporating the original text), and also find out what happened before the first entry, from the perspective of the captain. He is gay and sexually frustrated, on a ship full of men that he’d handpicked to suit his tastes:“hairless men from icy countries” (p. 22). He lost his lover Mikhail, he is alone, and his wet dreams start to take an increasingly eerie turn… paralleling and even presaging his waking life. It is well known how the story ends: with the ship beaching on the shore of England, and Dracula bounding off in animal shape. Of course, a retelling need not follow the original, but The Route of Ice and Salt generally keeps the plot intact, so it’s not likely to veer off course at the last moment. But how do we get there?

The details are gorgeously eerie; I found the first part, which relies less on the ship’s logs from Dracula, more poignant than the later sections. The story speeds up near the end. When the sailors begin disappearing, it all happens very fast, in contrast to the previously languid pace—despite the fact that the author considerably expanded the ship’s logs from Stoker’s book. I know that the short novel is an odd specimen, but here I would have loved to see more detail.

The Route of Ice and Salt is not just a story of erotic terror, or terrorized eroticism, but also a story of a failure of leadership. “Whom could I have saved?” the captain asks (p. 149), and the answer is just more death. This ties into his shortcomings: his self-absorption, his prioritizing his own desire over others’ wants. We see this at the very beginning, when he kisses one of the Romani servants loading the ship on the neck, without asking for permission. We understand immediately that he’s in the wrong. He grows and learns throughout the novel, he contemplates consent and critiques his own desire: “I know that Thirst is not evil in and of itself, nor Hunger a stigma that must be erased by fire and blood. […] It is what we are willing to do to feed an impulse that makes it dangerous.” [p. 177] It’s not gayness that makes anyone a monster. But it’s part of the horror that it’s all too late: we know no one will make it to England alive. What is new that we find out is about the captain’s past, and it adds to his careful portrayal as a flawed man who’s ultimately condemned to die.

This was not what I found frustrating; I don’t need my protagonists to be moral beacons, and I also think there should be room for queer tragedy in speculative fiction. What I thought was aggravating was the fact that despite the care and thought given to the captain’s character, his backstory, and so on, the novella readily slips into the exoticization of Roma and even plays this up compared to the original to make its points about consent and lack thereof. In fact, in Stoker’s original, the Roma—called “Szgany” in the novel, which seems to me to be a corruption of the corresponding Hungarian word—initially handled Dracula’s boxes of soil, but Mina Harker thought it had been the much less exoticized Slovaks who’d transported the boxes to the port. “He was brought from the castle by Szgany, and probably they delivered their cargo to Slovaks who took the boxes to Varna, for there they were shipped for London,” according to Stoker’s Dracula. To begin the novella with this exoticized portrayal of Roma was painful, and I considered not reading further. I did and was glad I did—this is the most sumptuous queer horror—but I found the opening sections the weakest of the story and wished they had been different.

I wanted to remark on one more thing at the end. The interiors—by Ampersand Book Interiors—are striking and on par with recent major-press novella releases; this is one area where small presses often have difficulty, to my dismay, but The Route of Ice and Salt is just good to look at and hold in my hands.

Next time we will follow with something possibly unexpected: queer speculative plays from before 2010! I found two and I’m planning on pairing them up. Until then, I hope you all had a great holiday break with plenty of rest. Did you read any great queer books over the last month or so? Let me know!