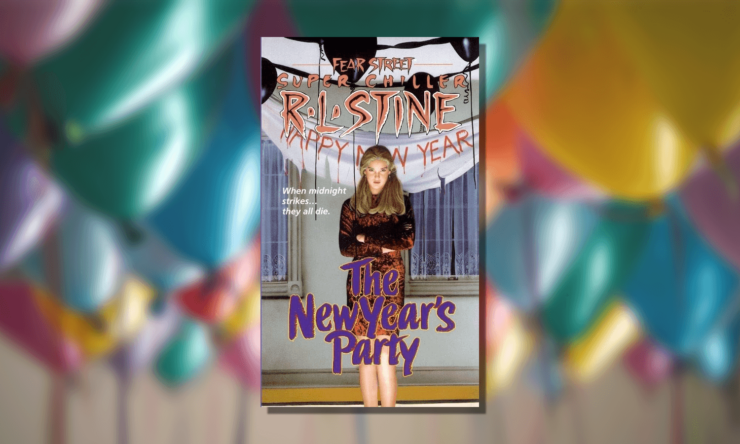

The new year is a pivotal moment, a liminal time in which the challenges and accomplishments of the past year stand in balance with the optimism of the new one, along with all of the intentions, goals, and resolutions for the next twelve months. It’s a good time for new beginnings and—depending on what you’ve been up to the previous year—to attempt to lay to rest terrifying memories, or bury dark secrets, in the hope of leaving those in the past as you turn a new calendar page. In R.L. Stine’s Fear Street Super Chiller The New Year’s Party (1995), however, the past and the present are complicatedly intertwined, stalling this transition and leaving the characters facing a range of horrors both human and supernatural.

The central theme of time, explored through the parallels between the past and the present, is apparent early on in Stine’s book, with the first section set in 1965 before a shift into the present moment. In both narratives, the central protagonists of the stories are (unsurprisingly, given the genre) teenagers and Stine’s main message seems to be that the more things change, the more they stay the same. Whether it’s 1965 or 1995, kids are jerks. They pick on and bully kids who are different or unpopular, and they pull practical jokes that skirt right up to the line of being inappropriate, hurtful, or even potentially dangerous, then are shocked when things go horribly wrong.

At a New Year’s eve party in 1965, Beth Fleisher is trying to have a good time with her boyfriend Todd Stevens, who she honestly is not all that into. Karen, who is their host and Beth’s friend, is nowhere to be found, and a bunch of tough guys are harassing a kid named Jeremy. Beth is worried about the party taking a dark turn, but it turns out that the worst is yet to come, when a group of guys bursts in, wearing ski masks and waving guns. Jeremy is once again singled out and tormented, as one of the men grabs Jeremy, presses his gun to Jeremy’s head, and pulls the trigger … but nothing happens, because it’s all a really mean, awful prank. The guys pull off their ski masks, laughing and Beth realizes that “The robbery is all a stupid joke … A dangerous, dumb joke” (13) that Karen had been in on the whole time. And as far as they’re concerned, the fun’s not over yet, as the fake robbers continue to get their laughs by teasing and ridiculing Jeremy for his terror as they held him at (fake) gunpoint. Furious and embarrassed, Jeremy runs off into the night, with Beth right behind him, as cranky Todd huffs that “maybe I’ll find someone that pays a little attention to me” (14). Beth trades one bruised male ego for another as she jumps in the car with Jeremy, trying to calm him down as he drives dangerously fast over icy roads, with a fogged up windshield obscuring his view. Jeremy hits a boy on the road then flees the scene over Beth’s panicked objections that they need to find whoever they hit, and after spinning out on the ice and crashing into a snowbank, Jeremy and Beth plummet over the side of a cliff.

This is when the story jumps ahead to the present day and while readers may be hoping that these contemporary teens may have learned from the mistakes of the past, there’s no such luck. Reenie Baker, Greta Sorenson, Artie Hodges, and new guy Ty Lanford are having a study session, working on some trigonometry problems. The only one missing is Reenie’s boyfriend Sean, though Artie jokes that Sean might be busy with Sandi Burke, who was “all over him” (27) after school. But Sean’s closer than Reenie thinks and when she opens her closet door she finds Sean’s corpse, with “Blank eyes” and “Gooey blood, dark and caked, [that] oozed over his hair” (29). Reenie seems pretty blase about her dead boyfriend, though this is because the group of friends are constantly playing jokes on one another, trying to convince the others that they’ve been murdered. Ty has been “killed” by a robber and Reenie has “drowned” in Greta’s bathtub, all to terrify and entertain their friends. While Sean’s latest “death” is par for the course, Reenie finds herself unsettled, thinking “Maybe we should stop playing this game … Maybe we should stop right now—tonight—before someone goes too far” (34). Why this particular night and this particular prank would be the one to make Reenie think that maybe they should pump the brakes on this whole “ha ha, you thought I was dead!” joke cycle is a mystery, but it doesn’t really matter because they don’t actually stop.

The next day at school, Reenie and her friends meet two new kids, Liz and her brother PJ. Liz is fun and outgoing and PJ is a bit more reserved. Liz confides in Reenie that PJ has a heart condition, which is why he’s a bit frail. His physical and social awkwardness make it tough for PJ to make friends and obviously, this means that PJ is the next target for the friends’ practical jokes, in an uneasy combination of “we don’t really like him” and “let’s make him feel like he’s part of the group.” The 1965 segment echoes through these conversations in the parallels of bullying and tasteless pranks, as despite the intervening decades, the teens still continue to make bad choices that hurt other people. In both 1965 and 1995, the girls who stand up for the guys being tormented piss off their boyfriends and run the risk of ending up alone, putting a premium on silent bystander complicity.

To be fair, the prank they pull on PJ is more dumb and potentially embarrassing than actually dangerous, as they talk sexy Sandi into asking PJ to be her date to Reenie’s Christmas party, kissing him in front of everyone, and then pretending to drop dead because the kiss “was too hot to handle!” (83). Sandi delivers a really convincing performance, then PJ panics and has a cardiac event of his own, dropping dead on Reenie’s living room floor. This obviously puts a damper on the party, the partygoers scatter, and when someone pulls into the driveway, Reenie and her friends decide the most logical course of action is to drag PJ’s body to the basement and hide him behind the furnace (which of course won’t look suspicious at all to any investigating authorities). The car was just someone turning around, the immediate threat of discovery is averted, and after a chance to think it over, Reenie and her friends decide that they really ought to call the cops and report PJ’s accidental death. After they call 911, they go back to the basement to bring PJ’s body back to the living room, but the body is gone. They decide PJ must have played a joke of his own on them and they have a really awkward conversation with the police officer who shows up, but it all seems to be wrapped up nicely … until Liz calls looking for her brother, who hasn’t come home.

PJ stays missing, no one is entirely sure whether he’s alive or dead, and then the kids who played the prank on him start turning up dead with their heads wrenched around backwards. Reenie and her friends try to justify their actions, reassure themselves that they didn’t actually do anything wrong, and focus on not getting murdered. Liz is understandably distraught, worried about her brother, and blaming Reenie and her friends for his disappearance. She ices out everyone but Ty, and the two of them become their own isolated—and romantic—unit. As the year draws to a close, however, Liz surprises them all by inviting Reenie and her friends to a New Year’s Eve party at her family’s house on Fear Street.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: if someone invites you to a party on Fear Street, just say no. Say you’re sick, stay in and wash your hair, curl up with a good book, whatever. Parties on Fear Street are never a good time. And Liz’s party is no exception. Reenie and her friends show up and find out they’re the only people who have been invited. When Liz invites them inside her mostly empty house, they find that “Liz had decorated the entire room in black. Black crepe paper draped the walls. Black balloons floated at the ceiling … It’s not a party. It’s a funeral, Reenie thought glumly” (168). Nobody’s having a good time. Liz may have invited them over for a party, but her ulterior motive is that she wants to get revenge on the kids who killed her brother before the clock strikes midnight.

And this is where the past and present collide, with a 1965 Shadyside High School yearbook serving as the hinge that brings them together. An old yearbook is an odd party favor, particularly when Liz leaves it out for them to find, then screams at them to “Leave that alone!” (169) when she sees them looking at it. Liz is the one who has been murdering their friends–and while turning people’s heads backwards seems like a remarkable strength for a fairly slight young woman, she actually has a range of hidden talents and powers. When you’re a vengeful ghost from 1965, it turns out you can do all kinds of things. Liz was Beth in 1965 and PJ was Jeremy, brother and sister Elizabeth and Philip Jeremy Fleisher, who are commemorated with a memorial page in the 1965 yearbook following their deaths in a New Year’s Eve car accident. Whether she’s called Liz or Beth, she was mad in 1965 and she’s still mad now, as she tells Reenie and her friends that “We died because some cruel kids played a mean joke on my brother … And now it’s thirty years later. Thirty years that we could have enjoyed, that we could have been alive in. Thirty years later—and you kids did the same thing … This time you’re going to pay for your joke. You’re going to pay for the thirty years we lost because of a joke” (185-6). But while there’s no question that the joke those kids played on Jeremy was mean, Jeremy isn’t exactly blameless, since it was his reckless driving that got them killed. And hitting someone with your car and then fleeing the scene is way worse than a practical joke, however cruel and tasteless that joke may be. But logic and reasoning hold no sway with Beth/Liz and Jeremy/PJ, who are dead, not happy about it, and want to make someone pay.

Beth/Liz and Jeremy/PJ aren’t sure why they were suddenly brought back from the dead, but getting revenge—albeit revenge on people who arguably haven’t done anything to deserve it—seems as good a reason as any, and they’re set on doing just that. But just like Reenie and her friends only had part of Liz and PJ’s story, there’s something they have missed, and it’s actually Ty who’s at the heart of this mystery. Just as Beth and Jeremy’s deaths echo through the thirty years between then and now, so does Ty’s, because he was the kid Jeremy hit with his car and left for dead on that long ago New Year’s Eve. Now in the final moments of 1995, he tells Beth/Liz that “It’s my turn … That’s why you two were brought back. So I could kill you. That’s why all three of us were brought back” (191). Ty will now be able to get his revenge on Beth and Jeremy by killing Liz and PJ … or his ghost will kill their ghosts, anyway. There’s a metaphysical tussle as the three ghosts wrestle with one another while the clock strikes midnight and “They whirled around in a vicious circle, a circle of rage and revenge. Faster, still faster. A ghostly whirlwind … Then it stopped. And the three ghosts began to fade. They grew dimmer. Dimmer. Bong! They faded into shadows. Then the shadows faded to smoke. A spinning column of smoke. Bong! The clock struck twelve. And fell silent. The smoke faded. And floated away” (192-3, emphasis original).

These final moments are a kind of odd inversion of the Christmas Carol narrative. There are three ghosts, but rather than being the spirits of the Past, Present, and Future, they have all come from the past and have taught some valuable lessons about these teens’ behavior and its repercussions in the present. Any potential impact on the future remains to be seen, but given that the awfulness of teenage behavior hadn’t come very far in the decades between 1965 and 1995, it’s tough to feel too optimistic. An even stronger parallel, however, is another of Stine’s Fear Street books: Halloween Party (1990). In that book, mysterious new girl Justine Cameron invites a bunch of kids to her house on Fear Street for a Halloween party (again, party on Fear Street? Just say no). After the night takes a terrifying turn, Justine reveals her ulterior motive: she is the now-grown child of the couple the teens’ parents killed while drag racing one Halloween night years ago. Much like the teens in The New Year’s Party, those in Halloween Party haven’t actually done anything to deserve Justine’s vengeful violence, but at least there’s a direct line of cause and effect, with the sins of the parents being carried onto the next generation. In The New Year’s Party, Reenie and her friends nearly die because they’re jerky teenagers, just like other, random jerky teenagers before them.

In both The New Year’s Party and Halloween Party, the past is never really past. Those in the present may be held accountable and punished for those long-ago wrongs, whether they deserve it or not. Even as new years begin, the past finds a way to get its vengeance.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.